Women and Climate Change – Mehreen Faruqi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Legislative Council

New South Wales Legislative Council PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Fifty-Sixth Parliament First Session Thursday, 11 August 2016 Authorised by the Parliament of New South Wales TABLE OF CONTENTS Motions .................................................................................................................................................... 57 Women of the Future Scholarship ....................................................................................................... 57 Newcastle Unity in Diversity Festival ................................................................................................. 57 Canterbury-Bankstown Bulldogs Donation to White Ribbon Australia .............................................. 57 Cooks Hill Surf Life Saving Club Redevelopment.............................................................................. 57 Business of the House .............................................................................................................................. 58 Postponement of Business ................................................................................................................... 58 Suspension of Standing and Sessional Orders: Order of Business ...................................................... 58 Order of Business ................................................................................................................................. 58 Committees ............................................................................................................................................. -

You Can Download the NSW Caring Fairly Toolkit Here!

A TOOLKIT: How carers in NSW can advocate for change www.caringfairly.org.au Caring Fairly is represented in NSW by: www.facebook.com/caringfairlycampaign @caringfairly @caringfairly WHO WE ARE Caring Fairly is a national campaign led by unpaid carers and specialist organisations that support and advocate for their rights. Launched in August 2018 and coordinated by Mind Australia, Caring Fairly is led by a coalition of over 25 carer support organisations, NGOs, peak bodies, and carers themselves. In NSW, Caring Fairly is represented by Mental Health Carers NSW, Carers NSW and Flourish Australia. We need your support, and invite you to join the Caring Fairly coalition. Caring Fairly wants: • A fairer deal for Australia’s unpaid carers • Better economic outcomes for people who devote their time to supporting and caring for their loved ones • Government policies that help unpaid carers balance paid work and care, wherever possible • Politicians to understand what’s at stake for unpaid carers going into the 2019 federal election To achieve this, we need your help. WHY WE ARE TAKING ACTION Unpaid carers are often hidden from view in Australian politics. There are almost 2.7 million unpaid carers nationally. Over 850,000 people in Australia are the primary carer to a loved one with disability. Many carers, understandly, don’t identify as a ‘carer’. Caring Fairly wants visibility for Australia’s unpaid carers. We are helping to build a new social movement in Australia to achieve this. Unpaid carers prop up Australian society. Like all Australians, unpaid carers have a right to a fair and decent quality of life. -

Legislative Council

ACHIEVE AUSTRALIA ..................................................................................................................... 27596 ADJOURNMENT ................................................................................................................................ 27595 ASSYRIAN AUTONOMOUS PROVINCE PROPOSAL ................................................................... 27550 AUTISM ADVISORY AND SUPPORT SERVICE AND AUTISM AWARENESS MONTH ......... 27550 BLUE MOUNTAINS BUSHFIRES ........................................................................................ 27586, 27595 BUSINESS OF THE HOUSE .................................................. 27551, 27552, 27552, 27557, 27557, 27559 COASTAL PROPERTY PROTECTION ............................................................................................. 27589 CONSTRUCTION INDUSTRY INSOLVENCY ................................................................................ 27595 COOTES TRANSPORT ...................................................................................................................... 27594 CRIMES AMENDMENT (INTOXICATION) BILL 2014 ................................................................. 27593 FRIEDRICH AUGUST VON HAYEK ............................................................................................... 27598 HOME SCHOOLING .......................................................................................................................... 27593 INTERNATIONAL WOMEN'S DAY 2014 ....................................................................................... -

High Notes, Vol 20 No 9, March 29 2019

H The Weekly Newsletter of Sydney Boys High School Vol 19 No 09 29 March 2019 From the Principal happy to see! I wish I knew his name so you High Talent could personally praise him.” People on public I Congratulations to Hunar Verma (12T) on his transport take a close interest in the behaviour selection in the NSW All- of school students. The student referred to Schools cricket team. knows he did the right thing. Acting honourably Our first XI qualified for is its own reward. the Davidson Shield Knockout cricket finals Literacy Development in Years 7-10 G for the second As part of our ‘lighting up literacy’ objective in successive year – well our School Plan, we intend all students to done, boys! High was engage in literacy development. In a nutshell, represented strongly in we want our students to be more skilful, the Combined GPS accurate, versatile and purposeful writers. We basketball teams – want them to read more widely, analyse more H Julian Markworth-Scott (firsts) and Noah closely and listen more acutely. There is an Casaclang, Eoin Fitz-Gerald, Kwabena Brefo ongoing whole school emphasis on writing with and Kobe Shannon (seconds). Congratulations! a key focus each term – audience – sentence Lachlan HO (11T) won a bronze medal in the construction – ideas generation and vocabulary. Open Men’s Foil at the season opener Staff are supported by DoE generated competition. Well done to Klimenty Tsoutsmann resources. All students in Years 7-9 will (9S) who won a state competition in proficiency complete a series of in the Russian language. -

May 24 Statement Version 1

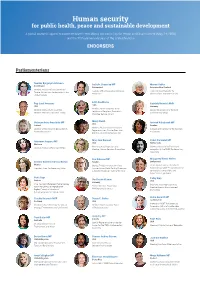

Human security for public health, peace and sustainable development A global women’s appeal to commemorate International Women’s Day for Peace and Disarmament (May 24, 2020) and the 75th anniversary year of the United Nations ENDORSERS Parliamentarians Senator Byrganym Aitimova Isabelle Chevalley MP Marian Hobbs Kazakhstan Switzerland Aotearoa-New Zealand Member, Foreign Affairs Committee. Founder of the Swiss Liberal Ecology Former Cabinet Minister for Former Kazakhstan Ambassador to the Movement Disarmament and Arms Control United Nations Edith DesMarais Rep Carol Ammons Gabriela Heinrich MdB USA USA Germany Member, New Hampshire State Member, Illinois State Assembly. Deputy Chairwoman of the SPD Legislature. Recipient, President's Member, Women Legislators’ Lobby parliamentary group Volunteer Service Award Mindy Domb Steinunn Þóra Árnadóttir MP Amineh Kakabaveh MP USA Iceland Sweden Member, Massachusetts House of Member of the Icelandic Delegation to Independent Member of the Swedish Representatives. Former Executive the Nordic Council Parliament. Director, Amherst Survival Center Mary Ann Dunwell Sadet Karabulut MP Ibtissame Azzaoui MP USA Netherlands Morocco Montana State Representative Member, Netherlands Parliament Member, Foreign Affairs Committee Member Human Services Committee delegation to the OSCE Parliamentary Assembly; Asa Eriksson MP Margareta Kiener Nellen Senator Gabriela Cuevas Barron Sweden Switzerland Mexico Deputy, Foreign Affairs Committee. Peace Women Across the World. President, Inter-Parliamentary Union Former Junior World Curling Champion Former Chair, OSCE PA Committee for & Sweden Handball Player of the Year democracy, human rights and humanitarian questions Petra Bayr Cathy Kipp Ute Finckh-Krämer Austria USA Germany Vice-President, European Parliamentary Colorado State Representative Former Member, Bundestag. Forum for Sexual & Reproductive Member, Energy & Environment PNND Council member Rights. -

Conference Wrap Up

Australian CouncilAustralian for Council for International 2019 Conference DevelopmentInternational Wrap-Up2019 Conference Development Wrap-Up Contents A Message from the Conference Organisers 05 Keynote Addresses 06 Keynote Panels 12 Ignite Sessions 20 Concurrent Sessions 24 Talanoa Sessions 36 Conference Dinner and ACFID Awards 38 ACFID Council Resolutions 42 Media 47 Delegate Feedback 50 Exhibitors 52 Suppliers 58 ACFID would like to acknowledge and thank the Bedegal and Gadigal people who are the traditional custodians of the land on which the 2019 ACFID Conference was held. We express special thanks to Aunty Lola Ryan for delivering the Welcome to Country. This document, including address and panel discussion summaries, is authored solely by ACFID. Please refer to the speaker video recordings for exact words used. THE 2019 ACFID CONFERENCE WAS GENEROUSLY SUPPORTED BY 2 ACFID 2019 CONFERENCE WRAP-UP 3 ACFID 2019 CONFERENCE WRAP-UP A Message from the ACFID Conference Organisers On behalf of the Australian Council for International Development, we would like to extend our sincere thanks to everyone who made this year’s Conference possible. The energy, enthusiasm, and innovative In a time of divisive politics, the prevalence of open conflicts, surges of populism, restrictions on civil society ideas brought from every speaker and and urgent environmental imperatives - NGOs are facing delegate, along with engaged and a changed development landscape. In addition, funding supportive sponsors, helped to make this methods for development are fluctuating and shifting, event a great success. with donors looking for alternative ways to deliver impact. Social innovation and alternative business structures are on the increase and young people are looking for ways to We were delighted to see nearly 400 attendees from over make their own mark on the future world they will be 170 organisations gathered at The Roundhouse at the faced with. -

The Wheeler Centre Presents Two Days of An

THE WHEELER CENTRE PRESENTS TWO DAYS OF AN UNAPOLOGETICALLY FEMINIST AGENDA Book Now at Melbourne broadside.wheelercentre.com Town Hall #broadside2019 broadside.wheelercentre.com Broadside and the Wheeler Centre respectfully acknowledge the Traditional Owners of the land on which we live and work. We pay our respects to the people of the Kulin Nations and all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Elders past, present and emerging. Welcome Womin djeka mar-ran biik biik, Boon Wurrung Nairm derp bordupren uther weelam. Welcome to my Country, the land of the great bay of the Boon Wurrung people, our beautiful home. I am proud to say that my grandmother, Louisa Briggs, was one of the women whose activism helped About Broadside shape the course of Australian history, by leading a Broadside is the new feminist ideas festival from campaign to stop the government selling the the Wheeler Centre. Over the weekend of 9 and 10 Coranderrk mission in the 1870s, where she lived November at Melbourne Town Hall, Broadside will with her family. The Argus described Louisa as present two days of unabashedly feminist programming, ‘a most resolute lady’ and she was often spoken spotlighting a remarkable line-up of international about as being strong minded, hardworking, known and local speakers, and delivering a powerfully for her kindness, her love of children, her humour, feminist agenda. Smart, funny, passionate people fearlessness and courage.” sharing their expertise and their stories. According to our tradition, our land has always been We’re told that ‘if you’re not outraged, then you’re not Our deepest thanks to all of those who came before And before the public programme, on Friday 8 protected by our creator Bundjil, who travels as an paying attention.’ Today, it’s overwhelming how much us; to those doing this work every day; and to the eagle, and by Waang, who protects the waterways requires and deserves our attention. -

The University of Sydney Women's

THE UNIVERSITY OF SYDNEY WOMEN’S COLLECTIVE PRESENTS: WOMEN’S HONI WEEK NINE, SEMESTER TWO, 2019 ANU RESIDENTIAL SO WE’VE DECRIMINALIZED COLLEGES STRIKE ABORTION. NOW WHAT? Residential colleges are historically Internally-conducted reports reveal Nothing that’s worth fighting for is easy so hard for will be tenuous and uncertain. ridden with epidemics of rape culture that eight out of the ten of the ANU’s to get. The ‘choice’ that we fight for does The pro-choice movement must therefore and hazing, with one in fifteen Australian undergraduate residential halls have been not magically come merely with the harness the momentum derived from its university students having reported slammed with the lowest rating possible removal of a formal ban. In other states success and keep pushing for substantive being sexually assaulted at least once in for their management of sexual assault. where abortion has been decriminalized choice, which lies in designated public 2015 and 2016. It isn’t news that colleges The halls were judged on both their for much longer than in NSW, getting an services, coverage under Medicare and are broadly unsafe for the students that policies regarding sexual misconduct and abortion remains just as inaccessible for the removal of heavy restrictions around they house. The Australian National the effectiveness of their application, and those who come from regional areas and GPs and pharmacies who can provide University (ANU) is Australia’s top-ranked were found to be desperately wanting. low socioeconomic backgrounds. If we let abortions. university, but it falls horrifically short of abortion services remain as inaccessible protecting the students on its campus. -

Why Isn't Weed Legal Here Yet? Why Does Sydney Traffic Suck?

HONIHONI SOITSOIT VOLVOL 9090 SEMSEM 11 WEEKWEEK 11 WhyWhy isn’tisn’t weedweed WhyWhy doesdoes SydneySydney WhatWhat doesdoes UNSWUNSW legallegal6 herehere yet?yet? traffictraffic12 suck?suck? havehave14 toto hide?hide? HERE’SHERE’S THETHE CONSPIRACYCONSPIRACY LETTERS https://www.dailytelegraph.com.au/newslocal/ inner-west/hsc-results-2014-janek-dre- ACKNOWLEDGEMENT OF COUNTRY CONTENTS vikovsky-named-first-in-course-for-a-re- We acknowledge the traditional custodians of this land, the Gadigal people of the Eora cord-five-subjects/news-story/23983ada5d- Nation. The University of Sydney – where we write, publish and distribute Honi Soit— 3 LETTERS The DMs 4370c36cae3e005ff8bd2a). Despite what the is on the sovereign land of these people. As students and journalists, we recognise editors ’36 may say, an “I” is certainly no our complicity in the ongoing colonisation of Indigenous land. In recognition of our 4 ANALYSIS substitute for a possessive apostrophe. DID YOU privilege, we vow to not only include, but to prioritise and centre the experiences PERSPECTIVE Definitely NOT of Indigenous people, and to be reflective when we fail to. We recognise our duty 8 However, to focus solely on my gripes of the to be a counterpoint to the racism that plagues the mainstream media, and to 12 FEATURE front cover would betray my much more sub- KNOW? adequately represent the perspectives of Indigenous students at our University. We a known cult stantial reservation about the edition which also wholeheartedly thank our Indigenous reporters for the continuing contribution CULTURE lies somewhere between that front cover, and 16 Mr. Sherriff, of their labour to our learning. -

Senator Portraits

46th Parliament: Senators Senator the Hon Senator Senator Senator Senator Eric Abetz Alex Antic Wendy Askew Tim Ayres Catryna Bilyk Senator for Tasmania Senator for Senator for Tasmania Senator for Senator for Tasmania South Australia New South Wales Senator the Hon Senator Senator Senator Senator the Hon Simon Birmingham Andrew Bragg Slade Brockman Carol Brown Matthew Canavan Senator for Senator for Senator for Senator for Tasmania Senator for Queensland South Australia New South Wales Western Australia Senator the Hon Senator the Hon Senator Senator Senator Kim Carr Michaelia Cash Claire Chandler Anthony Chisholm Raff Ciccone Senator for Victoria Senator for Senator for Tasmania Senator for Queensland Senator for Victoria Western Australia Senator the Hon Senator Senator Senator Senator the Hon Richard Colbeck Perin Davey Patrick Dodson Jonathon Duniam Don Farrell Senator for Tasmania Senator for Senator for Senator for Tasmania Senator for New South Wales Western Australia South Australia 1 Last updated 4 May 2021 46th Parliament: Senators Senator Senator the Hon Senator the Senator Senator Mehreen Faruqi David Fawcett Hon Concetta Alex Gallacher Katy Gallagher Fierravanti-Wells Senator for Senator for Senator for Senator for Australian New South Wales South Australia Senator for South Australia Capital Territory New South Wales Senator Senator Senator Senator Sarah Senator the Hon Nita Green Stirling Griff Pauline Hanson Hanson-Young Sarah Henderson Senator for Queensland Senator for Senator for Queensland Senator for Senator for -

Tharunka 2014

Week 11 - Week 12, Semester 2, 2014 First Published 1953 Volume 60, No. 13 University of NSW’s Independent Student Newspaper 2 EDITORIAL Editors’ Letter Hey Folks, Another semester drawing to a close, another Tharunka full of good stuff. Enjoy Issue 13! It's packed to the brim of the usual great news articles, reviews, satire, sports, and zero SRC election coverage (sorry - some red tape means we can't report on the elections this year.) Goodluck this week. xoxo Ammy and Freya, with Tina. Editors: Ammy Singh, Freya King Tharunka acknowledges the Be- team, unless expressly stated. Arc Acting Editor: Tina Giannoulis degal and Gadigal people, the tra- accepts no responsibility for the ac- Copy Editor: Araz Eleyasian ditional custodians of the land on curacy of any of the opinions or in- Design: Chere De Koh which the University stands. formation contained in this issue of Comic illustrations: Dom Foffani, Tharunka is published periodically Paden Hunter Tharunka. Any complaints should by Arc @ UNSW. The views ex- be made in writing to the Market- Contact: pressed herein are not necessarily ing & Publications Coordinator. [email protected] the views of Arc, the Representative PO Box 173, Kingsford, NSW, 2032 Council or the Tharunka editing EDITORIAL 3 Calendar Tuesday 14 October: Volunteer Expo + SRC BBQ Main Library Walkway from 11am to 2pm What happens in caucus, stays in caucus… Been thinking about giving back? Keen to get experience with some of the best volunteer pro- grams out? Unsure where to start? Then stop in on your way to a study sesh for all the info you except in Labor Left could want as well as a barbeque to keep you going! Who is leaking unredacted minutes from UNSW Labor Left Stu- Anti-Poverty Week Trivia Night dents’ (LLS) caucus meetings to their traditional rivals over in UNSW Beer Garden, Roundhouse at 5pm Labor Right, a.k.a. -

Antarctic Odyssey in the Footsteps of SIR Douglas Mawson

Never Stand Still ANTARCTIC ODYSSEY IN THE FOOTSTEPS OF SIR DOUGLAS MAWSON BILL GATES THE CHINA QUESTION ROBOTIC LOVE How the world’s richest man As China ties strengthen, can we The future of interactive inspires a generation have our cake and eat it too? technology UNIKEN • Contents UNIKEN WINTER 2013 COVER STORY In the footsteps of Mawson 8 FEATURES Eye on the future 6 Lessons from the Bronx 7 Path to independence 11 The China question 12 YOUR TIME STArts now … Battle of the minds 15 MEHREEN FARUQI, ASB Where there’s a will 18 Environmental engineer, climate change What policies do you hope to influence OPINION activist and feminist, Mehreen Faruqi in the Greens? Decriminalising abortion Show us the plan 16 is the first Muslim woman to enter an in NSW, stopping hunting in national Australian parliament. She hopes her parks, the creation of a world-class Referendum realpolitik 17 appointment by the NSW Greens will lead integrated transport system and to more diversity in our legislature. addressing climate change. ARTS “I want to change the stereotypical How do you reconcile Green politics Robotic love 19 views people have about Muslim women,” with your faith? We live in a democracy she says. “I’ve never been defined by my Resistance is futile 20 and a secular system of governance that religion in any of my leadership roles – I’m should allow societies of different faiths not a religious spokesperson. The politics REGULAR and beliefs to come together without I’ll be advocating relate to social justice, fear of discrimination.