The Efficacy of a Program for of the University of Manitoba in Partial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BEAR Book Activity Family Learning Activities That Develop Readers Ready for School

Goodling Institute Family Learning Be Excited About Reading Activities BEAR Book Activity Family Learning Activities that Develop Readers Ready for School Read the title of the story and ask your child why they think that Corduroy wants a pocket. Write down how they think he will use the pocket. While reading refer to what your child has predicted. The story Before Reading begins with a mother and her daughter going to the laundromat. Talk with your child about what happens at the laundromat. Building background knowledge before reading helps children to better understand what they read. Read Together A Pocket for Corduroy* Don Freeman Corduroy goes to the crowded laundromat where he searches for a pocket of his own. What happens when he is left over night in the laundromat? *This book is also available in Spanish After Reading Clues in a Pocket You will need: • Envelopes to use as pockets • Drawing paper • Pencil Ask your child to draw a picture and to put it in the envelope. Help your child write clues on the outside of the envelope. Then play a guessing game together to figure out the picture in the envelope. Switch roles, and you draw the picture and make some clues. Teddy Bear, Teddy Bear Teddy bear, teddy bear, Teddy bear, teddy bear, Encourage Touch the ground, Say your prayers, your child to Teddy bear, teddy bear, Teddy bear, teddy bear, perform the Turn around, Turn down the light, actions in the poem as you Teddy bear, teddy bear, Teddy bear, teddy bear, read it aloud. Walk upstairs Say good night. -

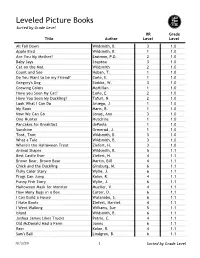

Book List Sorted by Grade Level

Leveled Picture Books Sorted by Grade Level 1 RR Grade Title Author Level Level All Fall Down Wildsmith, B. 3 1.0 Apple Bird Wildsmith, B. 1 1.0 Are You My Mother? Eastman, P.D. 2 1.0 Baby Says Steptoe 3 1.0 Cat on the Mat Wildsmith 2 1.0 Count and See Hoban, T. 1 1.0 Do You Want to be my Friend? Carle, E. 1 1.0 Gregory's Dog Stobbs, W. 3 1.0 Growing Colors McMillan 1 1.0 Have you Seen My Cat? Carle, E. 2 1.0 Have You Seen My Duckling? Tafuri, N. 2 1.0 Look What I Can Do Aruego, J. 1 1.0 My Book Maris, R. 1 1.0 Now We Can Go Jonas, Ann 3 1.0 One Hunter Hutchins 1 1.0 Pancakes for Breakfast dePaola 1 1.0 Sunshine Ormerod, J. 1 1.0 Toot, Toot Wildsmith, B. 3 1.0 What a Tale Wildsmith, B. 3 1.0 Where's the Halloween Treat Ziefert, H. 3 1.0 Animal Shapes Wildsmith, B. 5 1.1 Best Castle Ever Ziefert, H. 4 1.1 Brown Bear, Brown Bear Martin, Bill 4 1.1 Chick and the Duckling Ginsburg, M. 6 1.1 Fishy Color Story Wylie, J. 6 1.1 Frogs Can Jump Kalan, R. 4 1.1 Funny Fish Story Wylie, J. 6 1.1 Halloween Mask for Monster Mueller, V. 4 1.1 How Many Bugs in a Box Carter, D. 6 1.1 I Can Build a House Watanabe, S. -

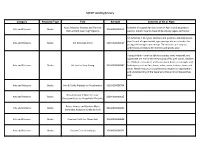

SCECP Lending Library

SCECP Lending Library Category Resource Type Title Barcode Contents of Kit or Note April: Patterns, Projects and Plans to A wealth of support for the month of April including posters, Arts and Patterns Books 33104000000019 Perk up Early Learning Programs awards, bulletin boards, basic skills activity pages, and more! Art Activities A to Z gives teachers and parents a detailed lesson plan format of open-ended, age- appropriate art activities for Arts and Patterns Books Art Activities A to Z 33104000000027 young children ages one and up. The activities are easy-to- understand and follow for children and adults alike. Young children have the ability to create, view, interpret, and appreciate art. Art for the Very Young offers over 50 art activities for children to create art and learn about basic art concepts and Arts and Patterns Books Art for the Very Young 33104000008947 techniques, such as line, shape, color, space, texture, form, and value. Watch how your young learners acquire an appreciation and understanding of the featured artists and techniques they use! Arts and Patterns Books Arts & Crafts Projects for Preschoolers 33104000008764 Beautiful Junk II: More Creative Arts and Patterns Books 33104000000035 Classroom Uses for Recyclable Materials Better Homes and Garden: More Arts and Patterns Books 33104000008863 Incredibly Awesome Crafts for Kids Arts and Patterns Books Creative Crafts for Clever Kids 33104000008848 Arts and Patterns Books Cut and Create! Holidays 33104000008731 Category Resource Type Title Barcode Contents of Kit -

Margret and HA Rey's Curious George and the Puppies

A Fish Out of Water Helen Marion Palmer Random House (1961) Summary: Illus. in color. "Comic pictures show how the fish rapidly outgrows its bowl, a vase, a cook pot, a bathtub."--The New York Times. Genre: Juvenile Fiction Number of Pages: 64 Language: English ISBN: 9780394900230 Reading Status: Unread Date Added: May 11, 2021 Tags: English Picture Books Notes: English Children Box 24 A Fishy Story Gail Donovan Night Sky Books (2001) Summary: Puffer has seen and done everything, and tells the most amazing stories, but when a new fish named Angel arrives, Puffer gets caught in a lie. Will anyone ever believe Puffer again? Genre: Fishes Number of Pages: 24 Language: English ISBN: 9781590140284 Reading Status: Unread Date Added: May 11, 2021 Tags: English Picture Books Notes: English Children Box 24 All about Corduroy Don Freeman Viking Press (1978) Summary: Corduroy: A toy bear in a department store wants a number of things, but when a little girl finally buys him he finds what he has always wanted most of all ; A pocket for Corduroy: A toy bear who wants a pocket for himself searches for one in a laundromat. Number of Pages: 60 Language: English ISBN: 9780681889217 Reading Status: Unread Date Added: May 11, 2021 Tags: English Picture Books Notes: English Children Box 24 All are welcome Alexandra Penfold Alfred A. Knopf (2018) Genre: Schools Number of Pages: 34 ISBN: 9780525579649 Reading Status: Unread Category: English Picture Books Date Added: January 28, 2021 Tags: English Picture Books Notes: Picture Books Children German Box #4 And Kangaroo Played His Didgeridoo Nigel Gray Scholastic Press (2005) Summary: You should have come to this Great Aussie Do, the guest list sure read like an Aussie Who's Who. -

Focus Units in Literature: a Handbook for Elementary School Teachers

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 247 608 CS 208 552 AUTHOR Moss, Joy F. TITLE Focus Units in Literature: A Handbook for Elementary School Teachers. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English,Urbana, Ill. y REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-1756-2 PUB DATE 84 NOTE 245p. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English,1111 Kenyon Rd., Urbana, IL 61801 (Stock No. 17562, $13.00 nonmember, $10.00 member). PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Use Guides (For Teachers) (052) Books (010) Viewpoints (120) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC10 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Childrens Literature; Content Area Reading;Content Area Writing; Curriculum Development; Curriculum Guides; Elementary Education; *LanguageArts; *Literature Appreciation; Models; PictureBooks; Reading Materials; Teaching Guides; *Unitsof Study ABSTRACT Intended as a guide for elementary schoolteachers to assist them in preparing and implementing specificliterature units or in de7eloping more long-term literatureprograms, this book contains 13 focus units. After defininga focus unit as an instructional sequence in which literatute isused both as a rich natural resource for developing language and thinkingskills and as the starting point for diverse reading and writingexperiences, the first chapter of the book describes the basiccomponents of a focus unit model. The second chapter identifiesthe theoretical foundations of this model, and the third chapterpresents seven categories of questions used in the focus unitsto guide comprehension and composition or narrative. The remaining 14chapters provide examples of the model as translated into classroom practice,each including a lesson plan for development,a description of its implementation, and a bibliography of texts. The units cover the following subjects:(1) animals in literature, (2) the works ofauthors Roger Duvoisin and Jay Williams, (3) the world aroundus,(4) literature around the world, (5) themes in literature, and (6)fantasy. -

Mcquerry Elementary Lexile Levels and Books New CCR Expectations

McQuerry Elementary Lexile Levels and Books New CCR Expectations Lexile Codes Grade Band 11-CCR: 1215-1355 AD (Adult Directed) Grade Band 9-10: 1080-1305 GN (Graphic Novel) Grade Band 6-8 955-1155 HL (High-Low) Grade Band 4-5 770-980 IG (Illustrated Guide) Grade Band 2-3 450-790 NC (Non-Conforming NP (Non-Prose) BR (Beginging Reader) Brian's winter R 1140 Cartoons & animation M 1090 Under the royal palms T 1070 The last princess The story of Princess Ka'iulani of Hawaii R AD1040 Our friend the dolphin N 1040 Pigs might fly R 1030 In the line of fire: Eight women war spies S 1020 Exploring the Titanic Q 980 Wildlife watching P 980 Alexander and the terrible, horrible, no good, very bad day L AD970 American tall tales Q 970 Can I Bring My Pterodactyl to School Ms. Johnson? M NC970 Amazing Sharks! O 940 Listening to crickets R 930 The girl who chased away sorrow T 920 Mr. Popper's Penguins T 910 Sounder T 900 Blueberries for Sal M AD890 The adventures of the shark lady Q 890 The Magic School Bus Fact Finder Bats M 890 Encyclopedia Brown Takes the Cake! Q 880 Ishmaal and the glass horse O NC870 Balto and the Great Race P 870 The Hundred Dresses O 870 How flamingos come to have red legs L NC860 Favorite medieval tales Q 860 The star fisher S 850 Graffiti I 840 The popcorn book M AD830 Volcano The eruption and healing of Mount St. Helens T 830 And then what happened, Paul Revere R 830 The leaving morning I AD820 Who Grows Up in the Ocean L NC810 Break That Code M 810 If you lived with the Cherokee Q 800 Happy birthday Martin Luther King L 800 -

Winnie the Pooh Study Guide

PLAZA THEATRICAL PRODUCTIONS Winnie the Pooh Study Guide Dear Teacher: We have created the following study guide to help make your students’ theater experience with Winnie the Pooh as meaningful as possible. For many, it will be their first time viewing a live theatrical production. We have learned that when teachers discuss the play with their students before and after the production, the experience is more significant and long-lasting. Our study guide provides pre- and post-performance discussion topics, as well as related activity sheets. These are just suggestions. Please feel free to create your own activities and areas for discussion. We hope you and your class enjoy the show! Background In 1926, A.A. Milne wrote Winnie-the-Pooh for his son, Christopher Robin Milne. On his first birthday, Christopher received a stuffed toy he called Edward, and who was later re-named Winnie (after a black bear at the London zoo), and Pooh (after a swan, as mentioned in a poem in Milne’s When We Were Very Young.) Other characters in the story were based on Christopher’s other stuffed animals, including the donkey Eeyore, Kanga and Baby Roo, and Piglet. Owl and Rabbit were inspired by animals who lived in the forest nearby. Illustrator Ernest H. Shepard based the look of his drawings on Christopher Robin Milne and his toys. The original stuffed animals are currently on display at New York City’s Donnell Public Library. Pre-Performance Discussion 1. Read A.A. Milne’s Winnie-the-Pooh with your students. Much of the dialogue (and many of the songs’ lyrics) come directly from Milne’s writing, and children will enjoy hearing the familiar words and turns of phrase. -

Tools & Tips for Reading with Children

TOOLS & TIPS FOR READING WITH CHILDREN ® CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .........................................................................................................................3 ACTIVITY GUIDES: Corduroy by Don Freeman ....................................................................................................5 Chicka Chicka Boom Boom by Bill Martin Jr. and John Archambault ...................................... 13 The Cat in the Hat by Dr. Seuss ...........................................................................................21 MORE TIPS FOR READING WITH CHILDREN ............................................................................... 26 ADDITIONAL RESOURCES .........................................................................................................31 TOOLS & TIPS FOR READING WITH CHILDREN INTRODUCTION Children who cannot read well by the end of third grade are four times as likely to drop out of high school.1 Yet millions of American children get to fourth grade without reading well. To address this critical issue, United Way Worldwide has launched a national initiative to boost early grade reading. If you are in a position to read with children, you can play a critical role in helping create strong readers and better learners. Research has shown that children learn best when they are engaged and having fun. United Way has prepared this booklet to help volunteers, parents, caretakers, teachers and others who read with young children make reading more fun and help boost children’s literacy -

Reading List for Students Entering Kindergarten and First Grade

Reading List for Students Entering Kindergarten and First Grade Author Title Book Level Points Test Anno, Mitsumasa Anno's Counting Book NOTHING LISTED IN AR BOOKFIND Anno, Mitsumasa Anno's Alphabet NOTHING LISTED IN AR BOOKFIND Barrett, Judith Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs 4.30 0.50 5463 Bemelmans, Ludwig Madeline 3.10 0.50 5478 * Bemelmans, Ludwig Madeline and the Bad Hat 3.60 0.50 11377 Bemelmans, Ludwig Madeline and the Cats of Rome 3.50 0.50 125262 Bemelmans, Ludwig Madeline and the Gypsies 3.80 0.50 7378 Bemelmans, Ludwig Madeline in London 3.20 0.50 7578 Berenstain, Stan and Jan Berenstain Bears and the Messy Room 4.10 0.50 7462 Berenstain, Stan and Jan Berenstain Bears and the Sitter 3.40 0.50 7469 Berenstain, Stan and Jan Berenstain Bears Go To School 3.20 0.50 7487 Berenstain, Stan and Jan Berenstain Bears Moving Day 3.70 0.50 7493 Bridwell, Norman Clifford and the Big Parade 2.40 0.50 19215 ** Bridwell, Norman Clifford and the Big Storm 2.10 0.50 10511 Bridwell, Norman Clifford and the Grouchy Neighbors 2.00 0.50 14608 Bridwell, Norman Clifford at the Circus 2.10 0.50 14609 Bridwell, Norman Clifford Goes to Dog School 1.90 0.50 73309 Bridwell, Norman Clifford Goes to Hollywood 2.00 0.50 41849 Bridwell, Norman Clifford Goes to Washington 2.70 0.50 86751 Bridwell, Norman Clifford the Big Red Dog 1.20 0.50 6059 Brown, Marcia Stone Soup 3.30 0.50 5491 Brown, Margaret Wise Goodnight, Moon 1.80 0.50 7218 Brown, Margaret Wise Runaway Bunny 2.70 0.50 7292 Brunhoff, Jean de The Story of Babar 3.90 0.50 34898 Burton, Virginia Lee The Little House 4.20 0.50 5230 Burton, Virginia Lee Mike Mulligan and His Steam Shovel 4.40 0.50 5484 Carle, Eric The Very Hungry Caterpillar 2.90 0.50 5496 Carle, Eric The Grouchy Ladybug 2.80 0.50 5514 Carle, Eric The Very Busy Spider 1.30 0.50 36015 Carle, Eric The Very Quiet Cricket 3.00 0.50 36523 Daugherty, James Andy and the Lion 3.60 0.50 28782 Eastman, P.O. -

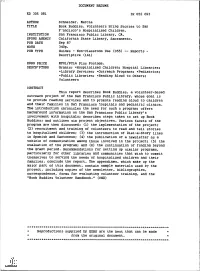

ED305081.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 305 081 IR 052 693 AUTHOR Schneider, Marcia TITLE Book Buddies. Volunteers Bring Stories to San r:ancisco's Hospitalized Children. INSTITUTION San Francisco Public Library, CA. SPONS AGENCY California State Library, Sacramento. PUB DATE Sep 87 NOTE 340p. PUB TYPE Guides - Non-Classroom Use (055) -- Reports - Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE MFO1 /PC14 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Grants; *Hospitalized Children; Hospital Libraries; *Library Services; *Outreach Programs; *Pediatrics; *Public Libraries; *Reading Aloud to Others; Volunteers ABSTRACT This report describes Book Buddies, a volunteer-based outreach project of the San Francisco Public Library, whose goal is to provide reading services and to promote reading aloud to children and their families in San Francisco hospitals and pediatric clinics. The introduction chronicles the need for such a program; offers background information on the San Francisco Public Library's involvement with hospitals; describes steps taken to set up Book Buddies; and outlines six project objectives. Various facets of the program are then discussed: (1) the implementation of the project; (2) recruitment and training of volunteers to read and tell stories to hospitalized children; (3) the introduction of Dial-a-Story lines in Spanish and Cantonese; (4) the publication of a newsletter as a vehicle of communication among those involved in the project; (5) the evaluation of the program; and (6) the continuation of funding beyond the grant period. Recommendations for setting up similar programs, particularly for other libraries and communities that wish to commit themselves to serving the needs of hospitalized children and their families, conclude the report. The appendixes, which make up the major part of this document, contain sample materials used by the project, including copies of the newsletter, bibliographies, correspondence, forms for evaluating volunteer training, and the "Book Buddies Volunteer Handbook." (CGD) Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made * from the original document. -

Summer Reading List

Dear KDS Parents, Summer is here! And summer is a great time to read, whether it’s during an early quiet morning on the porch, a long lazy afternoon by the pool, or a cool firefly-filled evening in the backyard. We all need some “down time,” especially our kids with all the activities of the school year and summer. Escaping into the pages of a good book is a wonderful way to relax and recharge! Attached is a list of teacher recommended titles, divided by grade, to give you and your child a place to start. If your child finds an author he or she particularly likes, look for more books by that person. Making time for reading is a lifelong skill that can be developed at any age. To help you get started, here are some strategies of a reading family: 1. Read to your child. Read frequently and consistently, no matter the child’s age or reading ability. Research shows that children who are read to become better readers and develop better vocabularies. 2. Let your child see you read, whether it is the newspaper, a magazine or novel. Your own example is most valuable. 3. Encourage your children to read to others, whether it’s to siblings, to you, to grandparents, friends & neighbors, pets or even their stuffed animals. 4. Take your child to the public library to obtain his or her own library card! Use that card often and participate in any number of the wonderful summer reading programs in the area! 5. Frequent the many wonderful bookstores around St. -

Shelf List Rosalia School District All Ranges and Prefixes in the Collection

Shelf List Rosalia School District All ranges and prefixes in the collection. All circulations. Call Number Author Title Barcode Price Status Circs 8508 T 8508 $0.00 Lost 1 Bleach T 9122 $0.00 Lost 1 Bleach C T 9077 $0.00 Lost 1 book T 8187 $0.00 Lost 1 book of world records 2006 T 9385 $0.00 Lost 1 boxcar kids T 9592 $0.00 Lost 1 brave and the bold T 8472 $0.00 Lost 1 confessions of a closet catholic T 8669 $0.00 Lost 1 crisis T 9291 $0.00 Lost 1 draw 50 animals T 9086 $0.00 Lost 3 five little christmas trees T 9508 $0.00 Lost 1 the hoopster T 9910 $0.00 Lost 2 librarian T 8250 $0.00 Lost 1 Phantom Stallion T 8437 $0.00 Lost 1 The Revelation T 7840 $0.00 Lost 1 Tale of Despareaux T 8048 $0.00 Lost 1 Tiger Eyes T 8362 $5.99 Lost 1 Welcome to Camden Hall T 8800 $0.00 Lost 1 Bleach. T 9027 $0.00 Lost 1 Code Orange. T 8804 $0.00 Lost 1 The Kids of Einstein The Last Dinosaur. T 9585 $0.00 Lost 1 one-minute organizer. T 8345 $0.00 Lost 1 Nancy Krulik. On thin ice. T 9533 $5.00 Lost 1 Sarah L. Thomson. Amazing Tigers!. T 9506 $3.99 Checked Out 1 001.2 AMR Did you know? : new insights into a world that is full of T 2678 Available 7 001.64 BRA Bradbeer, Robin. The beginner's guide to computers T 2677 Available 2 001.64 COH Cohen, Daniel.