The Beat of a Different Drum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

District Census Handbook, Raichur, Part II

CENSUS OF INDIA, 1951 HYDERABAD STATE District Census Handbook RAICHUR DISTl~ICT PART II Issued by BUREAU OF ECONOMICS AND STATISTICS FINANCE DEPARTMENT GOVERNMENT OF HYDERABAD PRICE Rs. 4 I. I I. I @ 0 I I I a: rn L&I IdJ .... U a::: Z >- c( &.41 IX :::::J c;m 0.: < a- w Q aiz LI.. Z 0 C 0 ::. Q .c( Q Will 1M III zZ et: 0 GIl :r -_,_,- to- t- U Col >->- -0'-0- 44 3I:i: IX a: ~ a:: ::. a w ti _, Ii; _, oc( -~-4a4<== > a at-a::a::. II: ..... e.. L&I Q In C a: o ....Co) a:: Q Z _,4 t- "Z III :? r o , '"" ,-. ~ I.:'; .. _ V ...._, ,. / .. l _.. I- 11.1 I en Col III -....IX ....% 1ft > c:a ED a: C :::::J 11.1 a. IX 4 < ~ Do. III -m a::: a. DISTRICT CONTENTS PAOB Frontiapkce MAP 0.1' RAICHUR DISTRICT Preface v Explanatory Note on Tables 1 List of Census Tracts-Raichur District 1. GENERAL POPULATION T"'BLES Table A-I-Area, Houses and Population 6 : Table A-II-Variation in Population during Fifty Years '8 Table A-Ill-Towns and Villages Classified by Population '10- , Table A-IV-Towns Classified by- Population with Variations since 1901 12' Table A-V-Towns arranged Territorially with Population by Livelihood Clasles 18 2. ECONOMIC TABLES Table B-I-Livelihood Classes and Sub-Classes 22 Table B-I1--Secondary Means of Livelihood 28 8. SOCIAL AND CULTURAL TABLES Table D-I-(i) Languages-Mother Tongue 82 Table D-I-(ii) Languages-Bi1ingmtli~m- - -,-, Table D-II-Religion Table D-III-Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes Table D-VII-Literacy by Educational Standa'rds 4. -

Gram Panchayat Human Development

Gram Panchayat Human Development Index Ranking in the State - Districtwise Rank Rank Rank Standard Rank in in Health in Education in District Taluk Gram Panchayat of Living HDI the the Index the Index the Index State State State State Bagalkot Badami Kotikal 0.1537 2186 0.7905 5744 0.7164 1148 0.4432 2829 Bagalkot Badami Jalihal 0.1381 2807 1.0000 1 0.6287 4042 0.4428 2844 Bagalkot Badami Cholachagud 0.1216 3539 1.0000 1 0.6636 2995 0.4322 3211 Bagalkot Badami Nandikeshwar 0.1186 3666 0.9255 4748 0.7163 1149 0.4284 3319 Bagalkot Badami Hangaragi 0.1036 4270 1.0000 1 0.7058 1500 0.4182 3659 Bagalkot Badami Mangalore 0.1057 4181 1.0000 1 0.6851 2265 0.4169 3700 Bagalkot Badami Hebbali 0.1031 4284 1.0000 1 0.6985 1757 0.4160 3727 Bagalkot Badami Sulikeri 0.1049 4208 1.0000 1 0.6835 2319 0.4155 3740 Bagalkot Badami Belur 0.1335 3011 0.8722 5365 0.5940 4742 0.4105 3875 Bagalkot Badami Kittali 0.0967 4541 1.0000 1 0.6652 2938 0.4007 4141 Bagalkot Badami Kataraki 0.1054 4194 1.0000 1 0.6054 4549 0.3996 4163 Bagalkot Badami Khanapur S.K. 0.1120 3946 0.9255 4748 0.6112 4436 0.3986 4187 Bagalkot Badami Kaknur 0.1156 3787 0.8359 5608 0.6550 3309 0.3985 4191 Bagalkot Badami Neelgund 0.0936 4682 1.0000 1 0.6740 2644 0.3981 4196 Bagalkot Badami Parvati 0.1151 3813 1.0000 1 0.5368 5375 0.3953 4269 Bagalkot Badami Narasapura 0.0902 4801 1.0000 1 0.6836 2313 0.3950 4276 Bagalkot Badami Fakirbhudihal 0.0922 4725 1.0000 1 0.6673 2874 0.3948 4281 Bagalkot Badami Kainakatti 0.1024 4312 0.9758 2796 0.6097 4464 0.3935 4315 Bagalkot Badami Haldur 0.0911 4762 -

Animal Husbandry and Veterinary Services, KOPPAL District Super Specialities Hospitals ANIMAL HUSBANDRY Telephone Nos

Animal Husbandry and Veterinary Services, KOPPAL District Super Specialities Hospitals ANIMAL HUSBANDRY Telephone Nos. Postal Address with PIN Code Sl. No. Name of the Officer Designation Office Fax Mobile -- ---- - Veterinary Hospitals ANIMAL HUSBANDRY Telephone Nos. Sl. No. Name of the Officer Designation Postal Address with PIN Code Office Fax Mobile CVO (ADMN) VETERINARY HOSPITAL 1 Dr SHIVARAJ M.SHETTAR 08539-220023 - 9902135800 MAIN ROAD VETERINARY HOSPITAL KOPPAL- 583231 KOPPAL DIST KOPPAL HOSPITALS IN HOBLI CVO (I/C) VETERINARY HOSPITAL 2 Dr NISHANTH.C - - 9380528128 VETERINARY HOSPITAL ALAWANDI - 583226 KOPPAL TQ AND DIST ALAWANDI KOPPAL TQ AND DIST CVO (I/C) VETERINARY HOSPITAL 3 Dr SUNIL KUMAR PATIL - - 9741653200 VETERINARY HOSPITAL HITNAL - 583234 KOPPAL TQ AND DIST HITNAL KOPPAL TQ AND DIST CVO (I/C) VETERINARY HOSPITAL 4 Dr VINOD DIVATAR - - 9886934138 VETERINARY HOSPITAL IRAKALGADA - 583237 KOPPAL TQ AND DIST ALAWANDI KOPPAL TQ AND DIST ASST DIRECTOR (I/C) VETERINARY 5 Dr MALLAYYA.P.M 08533-271324 - 9972709497 ISLAMPUR ROAD VETERINARY HOSPITAL GANGAVATHI-583227 KOPPAL DIST HOSPITAL GANGAVATHI HOSPITALS IN HOBLI CVO (I/C) VETERINARY HOSPITAL 6 Dr ARUNGURU KANAKAGIRI GANGAVATHI TQ - - 9591637222 VETERINARY HOSPITAL KANAKAGIRI - 583283 GANGAVATHI TQ KOPPAL DIST KOPPAL DIST CVO (I/C) VETERINARY HOSPITAL 7 Dr ARUNGURU KARATAGI GANGAVATHI TQ KOPPAL - - 9591637222 VETERINARY HOSPITAL KARATAGI - 583229 GANGAVATHI TQ KOPPAL DIST DIST CVO (I/C) VETERINARY HOSPITAL 8 Dr MALLAYYA.P.M HULIHYDER GANGAVATHI TQ KOPPAL - - 9972709497 VETERINARY -

Koppal District

GOVERNMENT OF KARNATAKA DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE Pradhan Mantri Krishi Sinchayee Yojana (PMKSY) DISTRICT IRRIGATION PLAN KOPPAL DISTRICT 2016 CONTENTS Chapter Page Contents No No PMKSY - Introduction 1-7 I General Information of the district 8-30 II District water profile 31-34 III Water availability 35-44 IV Water requirement/ demand 45-62 V Strategic action plan for irrigation 63-101 Conclusions 102-103 Appendices 104-167 i LIST OF TABLES Table No Title of Tables Page No 1.1 District profile 10 1.2 Taluk wise population 11 1.3 Details of house holds 12 1.4 Large animal population 14 1.5 Small animal population 15 1.6 Rainfall pattern in Koppal district 17 1.7 Soil types of Koppal district 19 1.8 Slope characteristic 20 1.9 Soil erosion and runoff status 27 1.10 Land use pattern in Koppal district 29 2.1 Crop wise- season-wise irrigated area in Koppal 31 district 2.2 Area, Production and Productivity of major 33 agricultural crops 2.3 Status of irrigated area in Koppal district 34 3.1 Status of water availability 36 3.2 Status of ground water in Koppal district 38 3.3 Status of command area 41 3.4 Status of ongoing lift irrigation schemes 41 3.5 Source wise irrigated area 42 3.6 Water availability in Koppal district 43 4.1 Domestic water requirement /Demand of Koppal 48 district & projected for 2020 4.2 Water requirement of horticultural/ agril crops 52 4.3 Water requirement of livestock in Koppal district in 54 2012 and projected for 2020 4.4 Water demand for industries in Koppal district 56 4.5 Water demand for power generation in -

General Population Tables, Part II-A, Vol-XI

PRO. 97. A. (~) ;!,OOO CENSUS OI~ INDIA 1961 VOLUME XI MYSORE PART II-A GENERAL POPULATION TABLES K. BALASUBRAMANYAM OF THE INDIAN ADMINISTRATIVE SERVICE Superintendent of Census Operations, Mysore 1964 PRINTED IN INDIA BY THE DmECTOR, GOVERN1.-IENT CENTRAL PRESS, BANGALORE AND PUBLISHED BY THE MANAGER OF PUBLICATIONS, DELHI-8 Price: Rs. 6.25 nP. or 14sh. 7d. or $ 2.25 PART II-A GENERAL POPULATION TABLES ADMINISTRATIVE MAP OF MYSORE 8CAJ,.E ;zI a MILC:1 TO "IN INCH 32 I. o I V') oLU a::« Q_ '4" SEA Distn'cl .Jleaol QU&ttte"J _ TQ.luk Head 8..uartil'S o Sea. Sta.t~ bDU nao.''.!1 CONTENTS PAGES PAGES INTRODUCTION i-viii TABLE A-I AREA, HOUSES AND POPULATION 1-62 FLY LEAF 3-16 UNION TABLE A-I 17-18 STATE TABLE A-I 19-35 FLY LEAF TO ApPENDIX I TO TABLE A-I 37 ApPENDIX I Statement showing 1951 territorial units constituting the present set-up of Mysore 38-42 SUB-ApPENDIX TO ApPENDIX I Statement showing area for 1951 and 1961 of those Municipal Towns which have undergone changes in area since 1951 census 43 FLY LEAF TO ApPENDIX II 45 ApPENDIX II Number of villages with a population of 5,000 and over and Towns with a population under 5,000 46-49 LIST A TO ApPENDIX II Places with a population of under 5,000 treated as Towns for the first time in 1961 49 LIST B TO ApPENDIX II Places with a population of under 5,000 in 1951 which were treated as Towns in 1951 but have been omitted from the list of Towns in 1961 50 FLY LEAF TO ApPENDIX III 51 ApPENDIX III Houseless and Institutional Population 52-62 TABLE A-II VARIATION IN POPULATION DURING SIXTY YEARS 63-74 FLY LEAF 65-69 TABLE A-II 70-72 ApPENDIX State and Districts showing 1951 population according to their territorial jurisdiction in 1961, changes III area and population involved in those changes 73-74 TABLE A-III VILLAGES CLASSIFIED BY POPULATION 75-96 FLY LEAF 77-81 UNION TABLE A-III 82-83 STATE TABLE A-III 84-95 ApPENDIX Sub-Totals of Broader Population Size Groups 96 PAGES PAGES TABLE A-IV TOWNS AND TOWN-GROUPS CLASSIFIED BY POPULATION IN 1961 WITH VARIATION SINCE 1901 97-152 FLY LEAF 99-114 TABLE A-IV . -

Aquifer Map of Yalburga Taluk, Koppal District

Aquifer Map of Yalburga Taluk, Koppal District KODABALKATTI ") KATRALA BANDI ")GF ") GUNTMADU ") GOLRAGUDISI ") JHULKATTI ") CHIK BANNIGOL SIRAGUMPI ") ´ ") *# SIDLABHAVI ") GF BODUR SANKANUR *# ") ") HIRE ARLIHALLI CHIK BANNIGOL TANDA ") 1:62,000 MATRANGI ") KONSAGAR ") *# ") BALUTIGI CHIK MANNAPUR ") ") KALAKBANDI BUDKUNTI YEDDONI *# ") ") ") GULE HOSUR *# ") ") HAGEDDI BASAPUR ") *# ") KUTAKMARI JARKUNTI ") VANAJABHAVI *# *# NINGALBANDI ") ") ") MYAGERI ") BIRALDINNI BUNKAPPA ") ") CHAUDAPUR VAJJARBANDI HOSUR ") ") ") CHIK ARLIHALLI MARKATH GF ") ") *# *# TUMMARGUDDI TALKERI CHIK KOPPA TUNDA ") KALBHAVI ") ") *# MATALDINNI ") *# *# ") CHIK KOPPA *# *# GANDHAL ") ") CHIK WANKALKUNTI *# MARNAL GF ") ") *# MANDALMARI YAPALDINNI JERKUNTI ") ") GF ") SALBHAVI GF ") GF TARALKATTI GF MUDHOL ") ") GF GF UPPAL")DINNI *# NALAGOL ") GF *#HOSAHALLI *# ") HIRE WANKALKUNTI *# ") HANMAPUR ") TALUR MAKKALLI *# *# ") ") MADLUR *# *# GF *# ") *# KARMUDI *# *# NARASAPUR *# ") *# HULIGUD ") *# *# ") *# *# KATGIHALLI WIRAPUR ") GF KUDRIKOTGI ") YELBARGA *# ") UCHALKUNTI ") *# ") TIPANHAL HIRE WADARKAL ") ") ISUPNAGARA MURDI TANDA *# GF ") ") *# GF *# BUKANHATTI GF GODGERI ") ") *# *# *# HUNSIHAL CHIK MEGERI ") *# *# ") GF *# MURDI MALAK SAMUDRA ") ") *# GF GUNHAL ") *# *# GF *# GF GF GUTTUR ") GF KOLEHAL GUDGUNTI ") ") SANGNAL *# LGFAKSHAMANGUDDA *# ") CHIK MEGERI ") ") GF BEVUR BANDEHAL ") ") *# *# WANGERI ") *# *# *# GF *# *# *# *# GF MEDNERI KALLUR ") ") *# GF *# GF NELJERI WATPARWI TONDEHAL ") ") ") *# GF WATPARWI TANDA GF ") RAVANKI ADUR ") BAIRENAKANHALLI -

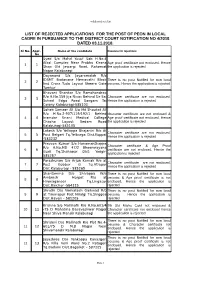

List of Rejected Applications for the Post of Peon in Local Cadre in Pursuance to the District Court Notification No 4/2018 Dated 03.11.2018

webhosted reje list LIST OF REJECTED APPLICATIONS FOR THE POST OF PEON IN LOCAL CADRE IN PURSUANCE TO THE DISTRICT COURT NOTIFICATION NO 4/2018 DATED 03.11.2018. Sl No. Appl . Name of the candidate Reasons for rejections No Syed S/o Mohd Yusuf Sab H.No.4 Afzal Complex Near Prabhu Kirana Age proof certificate not enclosed. Hence 1 1 Shop Old Jewargi Road, Rahemat the application is rejected Nagar Kalaburagi Dayanand S/o Jayaramaiah R/o IDSMT Badavane Hemavathi Block There is no post Notified for non local 2 2 Iind Cross Tuda Layout Sheera Gate persons. Hence the application is rejected Tumkur Bhavani Shankar S/o Ramchandrao R/o H.No.159 Jija Nivas Behind Sir Sai Character certificate are not enclosed. 3 3 School Edga Road Sangam Tai Hence the application is rejected Colony Kalaburagi-585103 Soheb Sameer Ali S/o Md.Shoukat Ali R/o H.No.2-907/119/192/1 Behind character certificate are not enclosed & 4 4 Inamdar Unani Medical College Age proof certificate not enclosed. Hence Chacha Layout Sedam Road the application is rejected Kalaburagi-585105 Lokesh S/o Yellappa Bhajantri R/o At Character certificate are not enclosed. 5 5 Post Belgeri Tq.Yelburga Dist.Koppal Hence the application is rejected -583232 Praveen Kumar S/o Hanamanthappa Character certificate & Age Proof R/o H.No.MD 47/2 Bheemrayana 6 6 certificate are not enclosed. Hence the Gudi Tq.Shahapur Dist: Yadgir- application is rejected 585287 Parashuram S/o Arjun Karnak R/o at Character certificate are not enclosed. -

Koppal Census 2011.Xlsx

Town/ Urban/ Total Population SC Population ST Population Sl No Name House Holds Village Rural Male Female Total Male Female Total Male Female Total 1 601230 Sankanur Rural 451 1064 1129 2193 196 213 409 36 38 74 2 601231 Katral Rural 136 341 328 669 27 29 56 48 56 104 3 601232 Sirgumpi Rural 249 670 643 1313 36 41 77 2 1 3 4 601233 Sompur Rural 212 484 475 959 7 7 14 20 31 51 5 601234 Hiremyageri Rural 846 2106 2128 4234 310 300 610 62 66 128 6 601235 Mudhol Rural 1436 3429 3467 6896 727 684 1411 65 73 138 7 601236 Chikoppa Rural 228 654 604 1258 482 445 927 2 3 5 8 601237 Tumurguddi Rural 396 1152 1083 2235 222 199 421 16 17 33 9 601238 Ballutgi Rural 805 2169 2192 4361 628 601 1229 81 84 165 10 601239 Jhulkatti Rural 157 420 401 821 81 72 153 64 50 114 11 601240 Bandi Rural 469 1255 1174 2429 180 161 341 62 50 112 12 601241 Kadbalkatti Rural 53 186 159 345 0 0 0 12 10 22 13 601242 Chikbannigol Rural 241 729 723 1452 315 341 656 32 32 64 14 601243 Konasagar Rural 361 1032 1026 2058 86 86 172 215 228 443 15 601244 Hagedhal Rural 155 445 429 874 26 25 51 166 162 328 16 601245 Bassapur Rural 213 508 531 1039 59 55 114 140 154 294 17 601246 Boon Koppa Rural 89 238 268 506 1 1 2 10 10 20 18 601247 Dammur Rural 331 972 976 1948 189 210 399 2 1 3 19 601248 Vajra Bandi Rural 367 1072 1053 2125 264 251 515 349 349 698 20 601249 Makkahalli Rural 64 195 190 385 18 10 28 46 47 93 21 601250 Salbhavi Rural 120 406 395 801 25 32 57 298 257 555 22 601251 Madlur Rural 164 450 463 913 85 90 175 6 8 14 23 601252 Lagalur Rural 31 79 82 161 7 8 15 29 32 -

Government of Karnataka Revenue Village, Habitation Wise

Government of Karnataka O/o Commissioner for Public Instruction, Nrupatunga Road, Bangalore - 560001 RURAL Revenue village, Habitation wise Neighbourhood Schools - 2015 Habitation Name School Code Management Lowest Highest Entry type class class class Habitation code / Ward code School Name Medium Sl.No. District : Koppal Block : GANGAVATHI Revenue Village : 29070200602 Govt. 1 5 Class 1 GLPS VIRUPAPUR GADDI 05 - Kannada 1 29070201201 Govt. 1 5 Class 1 GLPS BANDRAL 05 - Kannada 2 29070201202 Govt. 1 7 Class 1 GHPS URDU BANDRAL 18 - Urdu 3 Revenue Village : ACHARNARASAPUR 29070200101 29070200101 Govt. 1 8 Class 1 ACHARNARASAPUR GHPS ACHARNARSAPUR 05 - Kannada 4 Revenue Village : ADAPUR 29070200201 29070200201 Govt. 1 7 Class 1 ADAPUR GHPS ADAPUR 05 - Kannada 5 Revenue Village : ADAVIBHAVI 29070200301 29070200301 Govt. 1 5 Class 1 ADAVIBHAVI GLPS ADAVIBHAVI 05 - Kannada 6 Revenue Village : AGOLI 29070200401 29070200401 Govt. 1 8 Class 1 AGOLI GHPS AGOLI 05 - Kannada 7 Revenue Village : AKALAKUMPI 29070200501 29070200501 Govt. 1 5 Class 1 AKALAKUMPI GLPS AKALAKUMPI 05 - Kannada 8 Revenue Village : ANEGUNDI 29070200601 29070200601 Govt. 1 8 Class 1 ANEGUNDI GMHPS ANEGUNDI 05 - Kannada 9 29070200601 29070200605 Govt. 1 7 Class 1 ANEGUNDI GHPS URDU ANEGUNDI 18 - Urdu 10 29070200601 29070209801 Govt. 1 5 Class 1 ANEGUNDI GLPS SONIYANAGAR 05 - Kannada 11 29070200601 29070200608 Pvt Unaided 1 4 Class 1 ANEGUNDI HPS HOLY HEARTS ANEGUNDI 05 - Kannada 12 29070200601 29070200608 Pvt Unaided 1 4 Class 1 ANEGUNDI HPS HOLY HEARTS ANEGUNDI 19 - English 13 e-Governance, CPI office, Bangalore 1/1/2015 -10:29:26 AM 1 Government of Karnataka O/o Commissioner for Public Instruction, Nrupatunga Road, Bangalore - 560001 RURAL Revenue village, Habitation wise Neighbourhood Schools - 2015 Habitation Name School Code Management Lowest Highest Entry type class class class Habitation code / Ward code School Name Medium Sl.No. -

District Taluk Gram Panchayat Year Work Name Type of Building Estimated Amount Expenditure Expenditure for SC/ST Work Status

Estimated Expenditure For District Taluk Gram Panchayat Year Work Name Type Of Building Expenditure Work status Amount SC/ST Koppal Yelbarga Baligeri 2006-07 BS Slabs Flooring from Yamanappa House to Road at Konapura Village BS Slabs flooring 57000 56815 0 Progress Koppal Yelbarga Baligeri 2006-07 IEC IEC 178000 61490 0 0 Koppal Yelbarga Baligeri 2006-07 IEC IEC 178000 61490 0 Completed Koppal Yelbarga Baligeri 2006-07 BS Slabs Flooring from Yamanappa House to Road at Konapura Village BS Slabs flooring 100000 100000 0 Completed Koppal Yelbarga Baligeri 2006-07 Construction of Anganawadi Building at Balagei Anganavadi building 120000 120000 0 Progress Koppal Yelbarga Baligeri 2006-07 BS Slabs Flooring from Amarayya Poojara House to Road at Balageri BS Slabs flooring 200000 199333 0 Completed Koppal Yelbarga Baligeri 2006-07 Construction of Anganawadi Building at Balagei Anganavadi building 250000 249998 0 Completed Koppal Yelbarga Baligeri 2006-07 BS Slabs Flooring in SC Colony at Balageri (SC) BS Slabs flooring 100000 99653 99653 Completed Koppal Yelbarga Baligeri 2007-08 BS Slabs Flooring from Bajara to Padagatte at Balageri BS Slabs flooring 104000 0 0 Completed Koppal Yelbarga Baligeri 2007-08 Construction of Ledaes Levotry Room in Budagumpa Construction of Toilet 160000 0 0 Completed Koppal Yelbarga Baligeri 2007-08 BS Slabs Flooring in ST Colony at Tipparasanal (ST) BS Slabs flooring 200000 0 0 Completed Koppal Yelbarga Baligeri 2007-08 BS Slabs Flooring from Yamanappa House to Road at Konapooru (Spill Work) BS Slabs flooring 100000 -

The Hill of the 'Dwarves'

5/16/2017 The hill of the 'dwarves' The hill of the 'dwarves' Srikumar M Menon, May 16 2017, 0:04 IST Large expanse: A panoramic view of the megalithic site at Hire Benakal in Koppal district. × Sometime in the early 1800s, Rev G Keiss, a German missionary stationed at a mission in Betageri near Gadag, crossed River Tungabhadra from Beejanugger (Vijayanagara) near Anegundi and went on to Mallapur, where he enquired about the ‘dwarf houses of Yemmi Gudda’ that were rumoured to exist in the hills nearby. With some help from the headman of the village, he was able to locate them on the saddle of a hill north-west of Mallapur, scattered among enormous boulders that dotted the hills. In great excitement, he wrote to his friend Colonel Philip Meadows Taylor, the political superintendent at Surpur, who had shown him similar structures at Rajan Koluru, near Lingsugur. He described the various structures he saw there. Most eye-catching were what they called ‘cromlechs’ and ‘kistvaens’ – box-like structures made of tall, square stone slabs set on end; roofed over with large http://www.deccanherald.com/content/611704/hill-dwarves.html 1/4 5/16/2017 The hill of the 'dwarves' horizontal capstones. There were hundreds of them scattered among the boulders and Keiss made a rough plan of the site and sent it off to Meadows Taylor. Keiss urged the latter to abandon his notion that these structures were graves of ancient inhabitants of the land. He proposed the idea that the site, which he said was halfway between Mallapur and Yemmi Gudda (the Hill of the Buffaloes), was an abandoned settlement and that the stone structures were houses. -

Quesotionaire for Gram Panchayats

ijjaXbE1051 ., Public Disclosure Authorized . - . ~>, S- World Bank Funded Environmental s--- k<. Guidelines for "Karnataka Public Disclosure Authorized l | |t PanchayatStrengthening and l ). Poverty ARleviationProject" _4)Final Report Public Disclosure Authorized May 2005 PREPARED By . I, ;s*| ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT & POLICY RESEARCH INSTITUTE i ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~BANGALORE560 058 Public Disclosure Authorized g ) ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~SUB)INITTEDBY RLURALDEVELOPAIENT AN.D PANCH,xY.ATRAx DEPARTNiENT Go''T1RNAIENT OF KARA]TaoAKx r - \ ::l ---'S s ) t-R l : - - - TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION TITLE PAGE No . A Executive Summary _ 1 B Project Background 14 B. I Introduction 14 ______ lB.2 Project objective 14 B.3 Components _ 14 B.4 Implementing agency 14 _______ lB.5 Approach 16 _______ lB.6 Talukas to be focused in the Project 16 B.7 The Present Study background 18 B.7.1 Environment and Developmental Projects 18 B.7.2 Context 18 B.7.3 Methodology 19 ________ B.7.4 Structure of this report 21 ) C Policy, legislation and regulation 22 C. 1 Introduction --- 22 C.2 National 22 ) C.2.1 Policies - 22 ) ________ C.2.1.1 Policy Statement for Abatementof Pollution - 22 C.2.1.2 The National Forest Policy, 1988 - 23 C.2.1.3 The Waler and Air (Prevention and Control of - 24 ) Pollution) Acts ._l C.2.1.4 The Environment(Protection) Act, 1986 - 24 ) l C.2. 1.5 The Biological Diversity Act, 2003 - 25 ) _________ C.3 State _ 25 C.3.1.1 State Policy on Integrated Pest Management - 25 ) ~~~~~(IPM) ____ _ 03C.3.1.2 Joint Forest Management(JFM in Karnataka 25 C.3.1.3 The Mysore Land ImprovementAct, 1961 - 26 C.