Kahn V Kohlberg, Kravis, Roberts, &

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Form 3 FORM 3 UNITED STATES SECURITIES and EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C

SEC Form 3 FORM 3 UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 OMB APPROVAL INITIAL STATEMENT OF BENEFICIAL OWNERSHIP OF OMB Number: 3235-0104 Estimated average burden SECURITIES hours per response: 0.5 Filed pursuant to Section 16(a) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 or Section 30(h) of the Investment Company Act of 1940 1. Name and Address of Reporting Person* 2. Date of Event 3. Issuer Name and Ticker or Trading Symbol Requiring Statement EASTMAN KODAK CO [ EK ] Chen Herald Y (Month/Day/Year) 09/29/2009 (Last) (First) (Middle) 4. Relationship of Reporting Person(s) to Issuer 5. If Amendment, Date of Original Filed C/O KOHLBERG KRAVIS ROBERTS & (Check all applicable) (Month/Day/Year) CO. L.P. X Director 10% Owner Officer (give title Other (specify 2800 SAND HILL ROAD, SUITE 200 below) below) 6. Individual or Joint/Group Filing (Check Applicable Line) X Form filed by One Reporting Person (Street) MENLO Form filed by More than One CA 94025 Reporting Person PARK (City) (State) (Zip) Table I - Non-Derivative Securities Beneficially Owned 1. Title of Security (Instr. 4) 2. Amount of Securities 3. Ownership 4. Nature of Indirect Beneficial Ownership Beneficially Owned (Instr. 4) Form: Direct (D) (Instr. 5) or Indirect (I) (Instr. 5) Table II - Derivative Securities Beneficially Owned (e.g., puts, calls, warrants, options, convertible securities) 1. Title of Derivative Security (Instr. 4) 2. Date Exercisable and 3. Title and Amount of Securities 4. 5. 6. Nature of Indirect Expiration Date Underlying Derivative Security (Instr. 4) Conversion Ownership Beneficial Ownership (Month/Day/Year) or Exercise Form: (Instr. -

The Securities and Exchange Commission Has Not Necessarily Reviewed the Information in This Filing and Has Not Determined If It Is Accurate and Complete

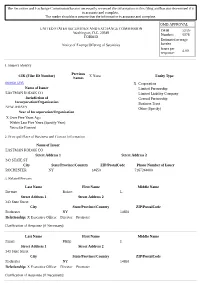

The Securities and Exchange Commission has not necessarily reviewed the information in this filing and has not determined if it is accurate and complete. The reader should not assume that the information is accurate and complete. OMB APPROVAL UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION OMB 3235- Washington, D.C. 20549 Number: 0076 FORM D Estimated average Notice of Exempt Offering of Securities burden hours per 4.00 response: 1. Issuer's Identity Previous CIK (Filer ID Number) X None Entity Type Names 0000031235 X Corporation Name of Issuer Limited Partnership EASTMAN KODAK CO Limited Liability Company Jurisdiction of General Partnership Incorporation/Organization Business Trust NEW JERSEY Other (Specify) Year of Incorporation/Organization X Over Five Years Ago Within Last Five Years (Specify Year) Yet to Be Formed 2. Principal Place of Business and Contact Information Name of Issuer EASTMAN KODAK CO Street Address 1 Street Address 2 343 STATE ST City State/Province/Country ZIP/PostalCode Phone Number of Issuer ROCHESTER NY 14650 7167244000 3. Related Persons Last Name First Name Middle Name Berman Robert L. Street Address 1 Street Address 2 343 State Street City State/Province/Country ZIP/PostalCode Rochester NY 14650 Relationship: X Executive Officer Director Promoter Clarification of Response (if Necessary): Last Name First Name Middle Name Faraci Philip J. Street Address 1 Street Address 2 343 State Street City State/Province/Country ZIP/PostalCode Rochester NY 14650 Relationship: X Executive Officer Director Promoter Clarification of Response (if Necessary): Last Name First Name Middle Name Haag Joyce P. Street Address 1 Street Address 2 343 State Street City State/Province/Country ZIP/PostalCode Rochester NY 14650 Relationship: X Executive Officer Director Promoter Clarification of Response (if Necessary): Last Name First Name Middle Name Kruchten Brad W. -

LIFE at KKR We Are Investors

LIFE AT KKR We are investors. But we're more than that. IT'S IN OUR DNA We're collaborative team players who are curious communities. We often measure success over about the world around us. We're passionate about years, not quarters. We value integrity in all that we always learning more and pushing to be better. do, whether it's presenting numbers accurately or Here, we're never finished growing or discovering being open and honest with a portfolio company new ideas. executive. People want to do business with those they like and trust. It's a mantra instilled in all of us People want to do business from the top down. with those they like and trust As a firm we manage investments across multiple asset classes and as individuals we are encouraged to think creatively to solve problems, explore opportunities, take on new responsibilities and challenges, put our clients first and contribute to our LIFE AT KKR | 2 We are investors. But we're more than that. Culture & Work Environment For over 40 years, our At KKR, you'll find a team of curious, driven, dedicated and intelligent professionals who enjoy working together. We all work collaborative approach hard to create a friendly environment that encourages asking continues to drive our culture questions and reaching out to others. Teamwork Entrepreneurial Spirit Integrity No matter where you sit in the Some of our best ideas come from It's at the heart of everything we do organization, you have the full giving people the time to explore, from our internal interactions to resources, network, skills and research and have conversations. -

Mercer Capital's Value Focus

MERCER CAPITAL’S VALUE FOCUS » THIRD QUARTER 2009 Mercer Capital provides asset managers, trust companies, and investment consultants Asset Management with corporate valuation, fi nancial reporting valuation, transaction advisory, portfolio valuation, and related services. Call Matt Industry Crow or Brooks Hamner at 901.685.2120 to discuss your needs in confi dence. Segment Focus: Alternative Asset Managers It is no surprise that companies employing massive amounts of leverage to make risky bets 20.00% on perceived mispricings and underperforming businesses have seen their own share prices 10.00% fl uctuate wildly over the last 12 months. Most 0.00% notably, Fortress Investment Group lost nearly 90% of its market cap in the fourth quarter of -10.00% 2008, which preceded a seven-fold increase in the months to follow. Most other publicly -20.00% traded hedge funds and private equity managers have experienced similar volatility, as our index -30.00% of alternative asset managers dropped roughly -40.00% half its value in the fourth quarter last year and is up almost 60% year-to-date. Investor anxiety, -50.00% credit disruptions, market deterioration and BX BAM FIG GLG OZM subsequent recovery, coupled with a gradual Alternative Asset Managers S&P 500 thawing of the credit markets and a few quarters of earnings surprises, are largely to blame for these variations. Political events may have also contributed to the volatility of these insider trading scheme could revitalize investor scrutiny and induce investments. Many analysts have suggested that compensation limits at even tighter regulation of alternative asset managers, whose reputation Wall Street fi rms that owe money to the government will unintentionally and AUM are still badly bruised from the catastrophic second half of benefi t hedge funds and other alternative asset managers, who may be last year. -

Private Equity in the 2000S 1 Private Equity in the 2000S

Private equity in the 2000s 1 Private equity in the 2000s Private equity in the 2000s relates to one of the major periods in the history of private equity and venture capital. Within the broader private equity industry, two distinct sub-industries, leveraged buyouts and venture capital experienced growth along parallel although interrelated tracks. The development of the private equity and venture capital asset classes has occurred through a series of boom and bust cycles since the middle of the 20th century. As the 20th century ended, so, too, did the dot-com bubble and the tremendous growth in venture capital that had marked the previous five years. In the wake of the collapse of the dot-com bubble, a new "Golden Age" of private equity ensued, as leveraged buyouts reach unparalleled size and the private equity firms achieved new levels of scale and institutionalization, exemplified by the initial public offering of the Blackstone Group in 2007. Bursting the Internet Bubble and the private equity crash (2000–2003) The Nasdaq crash and technology slump that started in March 2000 shook virtually the entire venture capital industry as valuations for startup technology companies collapsed. Over the next two years, many venture firms had been forced to write-off large proportions of their investments and many funds were significantly "under water" (the values of the fund's investments were below the amount of capital invested). Venture capital investors sought to reduce size of commitments they had made to venture capital funds and in numerous instances, investors sought to unload existing commitments for cents on the dollar in the secondary market. -

Private Equity Investors

Private Equity Investors Press Release Guernsey, Channel Islands, October 2, 2006 KKR Private Equity Investors Makes $282.3 Million Investment in Philips Semiconductors Business KKR Private Equity Investors, L.P. (Euronext Amsterdam: KPE) announced that it has invested approximately $282.3 million in connection with the publicly announced transaction to acquire, by an investor group that includes Kohlberg Kravis Roberts & Co. (KKR), a controlling stake in the semiconductors business of Royal Philips Electronics, formerly known as Philips Semiconductors International B.V. The semiconductors business has been renamed NXP B.V. Royal Philips Electronics recently announced the closing of this transaction, pursuant to which a consortium that includes KKR, Silver Lake Partners, Bain Capital, Apax Partners and AlpInvest Partners NV acquired an 80.1% stake in NXP B.V. and Royal Philips Electronics retained a 19.9% stake in NXP B.V. The $282.3 million total investment was comprised of a $250.0 million co-investment and $32.3 million of capital contributions to KKR-sponsored private equity funds. The amount invested by KPE in NXP B.V. represents approximately 6.0% of KPE’s net asset value as of August 30, 2006. About KPE KKR Private Equity Investors, L.P. (KPE) is a Guernsey-based limited partnership that seeks to create long-term value primarily by participating in private equity investments sponsored by KKR. Formed in April 2006 to provide complementary capital for KKR-sponsored private equity funds, KPE enables certain non-U.S. public market investors and certain other qualified investors to invest in select KKR- sponsored investments. -

Testimony of Richard Bressler Managing Director, Thomas H. Lee Partners on Behalf of the Private Equity Counci

Testimony of Richard Bressler Managing Director, Thomas H. Lee Partners on behalf of the Private Equity Council Subcommittee on Telecommunications & the Internet March 11, 2008 Introduction Good morning. ) am pleased to be here today to share some perspectives on the role of private equity in today’s rapidly evolving media and telecommunications market. ) appear in my capacity as a Managing Director at Thomas (. Lee Partners T(L, but my views are also offered on behalf of the Private Equity Council, the trade association representing many of the largest private equity firms doing business in the United States today. ) have been with T(L for two years. T(L is a leading private equity firm based in Boston, Massachusetts. We focus on identifying and obtaining substantial ownership positions in large, growth‐oriented companies where, in partnership with outstanding managers, we bring managerial and strategic expertise to accelerate the long‐term growth of our portfolio companies. We have found, throughout our long history, that building good companies into great ones is the best way to create value for our investors, our portfolio company employees and all stakeholders. As one of the oldest and most successful private equity firms, T(L has raised approximately $ billion of equity capital and invested in more than businesses with an aggregate purchase price of more than $ billion. We seek to build companies of lasting value while generating superior returns for our investors and operating partners. Prior to joining the firm, ) held senior management positions at Viacom and Time Warner, where ) served as CFO and as a senior executive with a close working relationships with, and a deep understanding of, both the editorial and business units. -

Permira Appoints Ryo Fujii As Head of Japan and Yoichiro Furuse As Chairman of Japan

Permira Appoints Ryo Fujii as Head of Japan and Yoichiro Furuse as Chairman of Japan Accelerating investment in Japanese Companies with Global Growth Ambitions Tokyo, July 15, 2015 – Permira, the global investment firm, is pleased to announce the appointment of Ryotaro (Ryo) Fujii as Managing Director and Head of Japan and Yoichiro Furuse as Chairman of Japan. Mr Fujii and Mr Furuse and will bring more than 50 years of combined experience in private equity and capital markets in Japan and will be responsible for running Permira’s long-standing Japan office in Tokyo and for further developing the firm’s activities in the country. Prior to joining Permira in 2015 as Head of Japan, Mr Fujii was at Kohlberg Kravis Roberts & Co., where he took a leadership role in the private equity team in Asia and was involved in a number of investments including Intelligence Holdings and Panasonic Healthcare. Previously, Mr Fujii was at Goldman, Sachs & Co. in New York and Tokyo working on financial advisory and principal investment activities for various Japanese companies. Prior to that, he served as the Japanese government official at the Ministry of Finance. Mr Fujii received a Bachelor in Law from the University of Tokyo, and a Master of Business Administration from Stanford University Graduate School of Business. Prior to joining Permira in 2007 as Senior Adviser, Mr Furuse held a number of management positions in leading Japanese companies, including Executive Vice President and CFO at Sanyo Electric and Senior Managing Director at Mazda Motor. Prior to that, Mr Furuse spent 32 years at Sumitomo Bank and served as Member of the Board, Senior Executive Director. -

2018 ESG, IMPACT, and CITIZENSHIP REPORT a MESSAGE from OUR CO-Ceos

invested. 2018 ESG, IMPACT, AND CITIZENSHIP REPORT A MESSAGE FROM OUR CO-CEOs. invested in tomorrow, today. At KKR, investing is what we do. For more than 40 years, on behalf of and alongside our clients, we have invested in compa- nies and in their futures. Over the years, we have grown, and so has our understanding of what it means to be a leading investor. By including the integration of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) considerations, we are focused on adding value to the investments we make for the investors we serve. Today, we are invested in demonstrating that companies can achieve meaningful impact as well as meaningful financial returns. We are invested in developing a diverse and talented workforce in our offices around the world. We are invested in being a purposeful and strategic partner in the communities where we live and work. And while we do not know what tomorrow will bring, we do know that we will be there, ready to invest in the people and products that will help us thrive in the future. HENRY R. KRAVIS and GEORGE R. ROBERTS Co-Founders, Co-Chairmen, and Co-CEOs invested in responsibility. 7 invested in impact. 19 invested in people. 29 invested in invested in communities. progress. 35 41 from our co-presidents. p.2 ESG management process. p.11 working at KKR. p.32 KKR at a glance. p.4 companies in action. p.16 volunteering globally. p.38 The KKR 2018 ESG, Impact, and Citizenship Report reflects our evolution as a global investor. The report has expanded to encompass the growth of our impact investing business and the deepening of our commitment to employees and communities. -

TPG the Blackstone Group Kohlberg Kravis Roberts Goldman Sachs

TPG Themay 2012 Blackstone Group Kohlbergprivate equity international Kravis Roberts Goldman page 37 Sachs Principal Investment Area The Carlyle Group CVC Capital Partners Apax Partners Apollo Global Management Bain Capital Oaktree Capital Management Hellman & Friedman General Atlantic Providence Equity Partners Cerberus Capital Management Warburg Pincus Advent International First Reserve Corporation Silver Lake Lone Star Funds Riverstone Holdings Leonard Green & Partners Thomas H. Lee Partners Golden Gate Capital BC Partners JC Flowers & Co. Terra Firma Capital Partners American Capital Teachers’ Private Capital NGP Energy Capital Management Fortress Investment Group Clayton Dubilier & Rice CPP Investment Board Bridgepoint PAI Partners AXA Private Equity Mount Kellett Capital EQT Partners Marfin Investment Group EnCap Investments Abraaj Capital Citi Capital Advisors Onex International Petroleum Investment Company Stone Point Capital TA Associates Hony Capital Nordic Capital ArcLight Capital Partners Equistone Partners Europe CDH Investments HitecVision AS JP Morgan Asset Management Charterhouse Capital Partners American Securities Capital Partners Mubadala Development Company Summit Partners Tiger Global Management Avista Capital Partners AlpInvest Partners Dubai International Capital MatlinPatterson Global Advisers GI Partners New Mountain Capital Kelso & Co. Denham Capital Management Sun Capital Partners Ares Management Lion Capital Investcorp Bank BSC Lindsay Goldberg Pamplona Capital Management H.I.G. Capital Doughty Hanson Accel Partners Berkshire Partners Vista Equity Partners WL Ross & Co. Welsh Carson Anderson & Stowe Centerbridge Capital Partners Energy Capital Partners Intermediate Capital Group Cinven Oak Hill Capital Partners page 40 private equity international may 2012 pei 300 TPG still top of the class It’s a second consecutive year at the top in Indonesian manager Northstar Pacific for TPG, whose remarkable fundraising (as it looks to get a foot in the door of machine accumulated a cool $49.9 bil- another high-potential emerging market). -

Guest Column: Europe: Finding the Sweet Spots For

guest column Europe: Finding the Sweet Spots for U.S. Investors Europe has traditionally been seen by U.S. private equity investors as a market rich in opportunities. While it remains true that the European private equity market is less mature than in the U.S., the market is becoming increasingly competitive. Operating as a U.S. private equity investor in Europe is complex, requiring an understanding of multiple national markets. Notwithstanding the fact that interesting opportunities for U.S. investors do exist, it is still too early to tell whether the initial U.S. entrants have been successful. This article will address the top questions that U.S. investors contemplating a European investment are posing. Is there lots of low-hanging fruit for funds has shifted strongly toward how in this issue.) These reforms will prove private equity investors in Europe? to add value to their transactions rather beneficial in the medium term by No, the European private equity market than merely relying on financial engi- increasing deal flow and flow of capital is at least as competitive as the U.S., neering to generate returns. into the asset class, but in the short- with more deals conducted by invest- Europe is one market these days, right? term significant differences exist in legislation between countries which will ment bank auction and fewer Wrong. Europe is still a multitude of continue to mean that market dynamics proprietary deals. different country markets each providing differ between states. The last few years have seen a surge differing opportunities and requiring Furthermore, the competitive situa- in European LBO activity. -

TPG Capital - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Page 1 of 6

TPG Capital - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Page 1 of 6 TPG Capital From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia TPG Capital (formerly Texas Pacific Group) is one of the largest private equity TPG Capital investment firms globally, focused on leveraged buyout, growth capital and leveraged recapitalization investments in distressed companies and turnaround situations. TPG also manages investment funds specializing in growth capital, venture capital, public equity, and debt investments. The firm invests in a broad range of industries including consumer/retail, media and telecommunications, industrials, technology, travel/leisure and health care. Type Private The firm was founded in 1992 by David Bonderman, James Coulter and William S. Industry Private equity Price III. Since inception, the firm has raised more than $50 billion of investor Predecessor Texas Pacific Group commitments across more than 18 private equity funds.[1] (s) Founded 1992 TPG is headquartered in Fort Worth, Texas and San Francisco, California.[2] The company has additional offices in Europe, Asia, Australia and North America. Founder(s) David Bonderman James Coulter William S. Price III Contents Headquarters Fort Worth, Texas San Francisco, California, U.S. ◾ 1 Private equity funds Products Leveraged buyouts, Growth capital, ◾ 2 History and notable Investments Venture capital ◾ 2.1 Founding Total assets $48 billion ◾ 2.2 Texas Pacific Group in the late 1990s ◾ 2.3 Texas Pacific Group in the early 2000s Website www.tpg.com ◾ 2.4 TPG and 2006-2007 Buyout Boom (http://www.tpg.com) ◾ 2.5 TPG and the Credit Crisis ◾ 2.6 Post Recession Activity ◾ 3 Newbridge Capital ◾ 4 Recognition ◾ 5 Notable employees ◾ 6 References ◾ 7 External links Private equity funds TPG has historically relied primarily on private equity funds, pools of committed capital from pension funds, insurance companies, endowments, fund of funds, high net worth individuals, sovereign wealth funds, and from other institutional investors.