Durham E-Theses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Channel Islands Great War Study Group

CHANNEL ISLANDS GREAT WAR STUDY GROUP Le Défilé de la Victoire – 14 Juillet 1919 JOURNAL 27 AUGUST 2009 Please note that Copyright for any articles contained in this Journal rests with the Authors as shown. Please contact them directly if you wish to use their material. 1 Hello All It will not have escaped the notice of many of us that the month of July, 2009, with the deaths of three old gentlemen, saw human bonds being broken with the Great War. This is not a place for obituaries, collectively the UK’s national press has done that task more adequately (and internationally, I suspect likewise for New Zealand, the USA and the other protagonists of that War), but it is in a way sad that they have died. Harry Patch and Henry Allingham could recount events from the battles at Jutland and Passchendaele, and their recollections have, in recent years, served to educate youngsters about the horrors of war, and yet? With age, memory can play tricks, and the facts of the past can be modified to suit the beliefs of the present. For example, Harry Patch is noted as having become a pacifist, and to exemplify that, he stated that he had wounded, rather than killed, a German who was charging Harry’s machine gun crew with rifle and bayonet, by Harry firing his Colt revolver. I wonder? My personal experience in the latter years of my military career, having a Browning pistol as my issued weapon, was that the only way I could have accurately hit a barn door was by throwing the pistol at it! Given the mud and the filth, the clamour and the noise, the fear, a well aimed shot designed solely to ‘wing’ an enemy does seem remarkable. -

Voice Pipe June 2021

TINGIRA AUSTRALIA TINGIRA AUSTRALIA VOICEPIPE JUNE 2021 TINGIRA Welcome National Committee BRAD MURPHY Tingira President ANZAC DAY National Roundup JOHN JRTS Billy Stokes PERRYMAN 1st Intake 2021 Stonehaven Medal TINGIRA.ORG.AU PATRON CHAIRMAN VADM Russ Crane Lance Ker AO, CSM, RANR QLD ACT TINGIRA NATIONAL COMMITTEE 2021 - 2024 PRESIDENT VICE PRESIDENT SECRETARY TREASURER Brad Murphy - QLD Chris Parr - NSW Mark Lee - NSW David Rafferty - NSW COMMITTEE COMMITTEE COMMITTEE COMMITTEE COMMITTEE Darryn Rose - NSW Jeff Wake - WA Graeme Hunter - VIC Paul Kalajzich - WA Kevin Purkis - QLD TINGIRA AUSTRALIA VOICEPIPE JUNE 2021 DISTRIBUTION & CORRESPONDENCE E. [email protected] W. tingira.org.au • All official communication and correspondence for Tingira Australia Association to be sent in writing (email) to the Association Secretary, only via email format is accepted. • No other correspondence (social media) in any format will be recognised or answered • VoicePipe is published 2-3 times annually on behalf of the Committee for the Tingira Australia Association Inc, for members and friends of CS & NSS Sobraon, HMAS Tingira, HMAS Leeuwin and HMAS Cerberus Junior Recruit Training Schemes FRONT COVER • VoicePipe is not for sale or published as a printed publication John Perryman with his • Electronic on PDF, website based, circulation refurbished antique 25 cm worldwide Admiralty Pattern 3860A signalling projector • Editors - Secretary & Tingira Committee • Copyright - Tingira Australia Association Inc. Photograph 1 January 2011 Meredith Perryman WHEEL to MIDSHIPS Welcome - Tingira National Committee ife is like a rolling predict that we move through stone, well so be the rest of 2021 with more L it. confidence on life than the Here at Tingira, we don’t experience of the 2020 Covid “ year. -

Appendix: Statistical Information

Appendix: Statistical Information Table A.1 Order in which the main works were built. Table A.2 Railway companies and trade unions who were parties to Industrial Court Award No. 728 of 8 July 1922 Table A.3 Railway companies amalgamated to form the four main-line companies in 1923 Table A.4 London Midland and Scottish Railway Company statistics, 1924 Table A.5 London and North-Eastern Railway Company statistics, 1930 Table A.6 Total expenditure by the four main-line companies on locomotive repairs and partial renewals, total mileage and cost per mile, 1928-47 Table A.7 Total expenditure on carriage and wagon repairs and partial renewals by each of the four main-line companies, 1928 and 1947 Table A.8 Locomotive output, 1947 Table A.9 Repair output of subsidiary locomotive works, 1947 Table A. 10 Carriage and wagon output, 1949 Table A.ll Passenger journeys originating, 1948 Table A.12 Freight train traffic originating, 1948 TableA.13 Design offices involved in post-nationalisation BR Standard locomotive design Table A.14 Building of the first BR Standard locomotives, 1954 Table A.15 BR stock levels, 1948-M Table A.16 BREL statistics, 1979 Table A. 17 Total output of BREL workshops, year ending 31 December 1981 Table A. 18 Unit cost of BREL new builds, 1977 and 1981 Table A.19 Maintenance costs per unit, 1981 Table A.20 Staff employed in BR Engineering and in BREL, 1982 Table A.21 BR traffic, 1980 Table A.22 BR financial results, 1980 Table A.23 Changes in method of BR freight movement, 1970-81 Table A.24 Analysis of BR freight carryings, -

Keystone State's Official Boating Magazine

-Keystone State's Official boating Magazine — - 1,"•• ."..1•0 Ara: 4711 a _ ti) VIEWPOINT On Wearing a PFD The weather was nice even though the temperature was a bit on the chilly side. The water temperature was cold because the ice had just broken up, but the fish were biting. After all, it had been a long winter and it was time to get out of the house and toss a few plugs at the bass that had been waiting since last fall. It was a fine day—fine, that is, until something unexpected occurred. No one will ever know exactly what happened. One minute he was in the boat; the next, he was in the water fighting for his life. He lost. Twice already in this short season, two Pennsylvania boaters lost their gam- ble with nature. Early season accidents continue to plague our boaters. Some accidents were almost unavoidable. Many were not. A little common sense would have prevented many of these tragedies. Fully half of last year's fatali- ties could have been avoided if the victims had only worn life jackets. Not wanting to wear a life jacket on a hot July .day is understandable. Not wearing one on a chilly spring day is simply ridiculous. Who do you think you are going to impress? What do you hope to gain—a little convenience? More freedom of movement? If you think a life jacket is going to inconve- nience you, think for a moment how inconvenienced your family would be if you didn't come home. -

Download Download

ARMAMENTS FIRMS, THE STATE PROCUREMENT SYSTEM, AND THE NAVAL INDUSTRIAL COMPLEX IN EDWARDIAN BRITAIN Professor Roger Lloyd-Jones History Department, Sheffield Hallam University Dr. Myrddin John Lewis History Department, Sheffield Hallam University This article examines the relationship between Britain’s armament firms and the state’s procurement system, presenting a case for a Naval Industrial Complex (NIC) in the years immediately before the Great War. It argues that in Edwardian Britain a nuanced set of institutional networks were established between the Admiralty and a small elite group of armament manufacturers. The NIC demonstrates the close collaboration between the armament firms supplying the Admiralty and between the Admiralty and an elite group of private contractors. This article concludes that the NIC did not lead to profiteering by contactors, and they did supply the warships and naval ordnance that enabled Britain to out build Germany in the naval race. This paper examines the relationship in Britain between the armaments industry and the military institutions of the state during the years preceding the Great War, when there were intensifying international tensions, and concerns over Britain’s defense capabilities. Through an assessment of the War Office (WO) and Admiralty procurement system, we apply John Kenneth Galbraith’s theory that businesses may establish institutional networks as “countervailing powers” to mediate business-state relations and, thus, we challenge the proposition that the state acted as a “monopsonist,” dominating contractual relations with private armaments firms.’ We argue that during the years prior to the war, Britain’s Naval Industrial Complex (MC) involved a strengthening collaboration between the British Admiralty and the big armament firms. -

William Schaw Lindsay: Righting the Wrongs of a Radical Shipowner Michael Clark

William Schaw Lindsay: righting the wrongs of a radical shipowner Michael Clark William Schaw Lindsay a perdu ses parents en 1825 à l’âge tendre de dix ans, il s'est enfui en mer en 1831 et il est rentré à terre âgé de vingt-cinq ans et certifié comme maître de bord. Il est devenu courtier de navires et a exploité les caprices du marché marin à la suite de l'abrogation des lois sur la navigation pour devenir armateur, établissant une compagnie de navigation spécialisée dans l'émigration vers l'Australie et affrétant des navires aux gouvernements français et britannique pendant la guerre criméenne. Élu député au parlement en 1854, il a favorisé les issues maritimes mais sa sympathie publique envers les États Confédérés pendant la guerre civile l'a mené vers des accusations que ses bateaux cassaient le blocus des États-Unis. Introduction “His family details are sketchy...”1 For a century and a half, many wrongs have been written about William Schaw Lindsay and this paper will attempt to clarify how and why he has been misrepresented. The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography claims that his family details are sketchy yet Lindsay was proud of his lowly origins and never concealed them. He was born during a gale on 19 December 1815 at the manse of his uncle, the Reverend William Schaw, in the county town of Ayr in South-West Scotland.2 Tragically, Lindsay’s father died four years later, followed by the death of his mother in 1825 and Lindsay wrote “From that moment I felt I was a child of poverty whose lot was to earn my bread by the sweat of my brow.’” 3 The childless minister and his wife willingly took Lindsay into the manse and sent him to Ayr Academy in the hope that he would become a Free Church minister like himself. -

Ships!), Maps, Lighthouses

Price £2.00 (free to regular customers) 03.03.21 List up-dated Winter 2020 S H I P S V E S S E L S A N D M A R I N E A R C H I T E C T U R E 03.03.20 Update PHILATELIC SUPPLIES (M.B.O'Neill) 359 Norton Way South Letchworth Garden City HERTS ENGLAND SG6 1SZ (Telephone; 01462-684191 during my office hours 9.15-3.15pm Mon.-Fri.) Web-site: www.philatelicsupplies.co.uk email: [email protected] TERMS OF BUSINESS: & Notes on these lists: (Please read before ordering). 1). All stamps are unmounted mint unless specified otherwise. Prices in Sterling Pounds we aim to be HALF-CATALOGUE PRICE OR UNDER 2). Lists are updated about every 12-14 weeks to include most recent stock movements and New Issues; they are therefore reasonably accurate stockwise 100% pricewise. This reduces the need for "credit notes" and refunds. Alternatives may be listed in case some items are out of stock. However, these popular lists are still best used as soon as possible. Next listings will be printed in 4, 8 & 12 months time so please indicate when next we should send a list on your order form. 3). New Issues Services can be provided if you wish to keep your collection up to date on a Standing Order basis. Details & forms on request. Regret we do not run an on approval service. 4). All orders on our order forms are attended to by return of post. We will keep a photocopy it and return your annotated original. -

BAE Systems Undertakings Review: Advice to the Secretary of State

%$(6\VWHPV 8QGHUWDNLQJV5HYLHZ $GYLFHWRWKH6HFUHWDU\RI6WDWH 1May © Crown copyright 2017 You may reuse this information (not including logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence. To view this licence, visit www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government- licence/ or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected]. Website: www.gov.uk/cma Members of the Competition and Markets Authority who conducted this inquiry John Wotton (Chair of the Group) Rosalind Hedley-Miller Jayne Scott Acting Chief Executive of the Competition and Markets Authority Andrea Coscelli The Competition and Markets Authority has excluded from this published version of the report information which the inquiry group considers should be excluded having regard to the three considerations set out in section 244 of the Enterprise Act 2002 (specified information: considerations relevant to disclosure). The omissions are indicated by []. Contents Page Executive summary and advice .................................................................................. 3 1. Executive summary ............................................................................................... 3 BAES .................................................................................................................... 4 Changes of circumstances .................................................................................... 5 Use of the Undertakings ...................................................................................... -

What Were the Investment Dilemmas of the LNER in the Inter-War Years and Did They Successfully Overcome Them?

What were the investment dilemmas of the LNER in the inter-war years and did they successfully overcome them? William Wilson MA TPM September 2020 CONTENTS 1. Sources and Acknowledgements 2 2. Introduction 3 3. Overview of the Railway Companies between the Wars 4 4. Diminishing Earnings Power 6 5. LNER Financial Position 8 6. LNER Investment Performance 10 7. Electrification 28 8. London Transport Area 32 9. LNER Locomotive Investment 33 10. Concluding Remarks 48 11. Appendices 52 Appendix 1: Decline of LNER passenger business Appendix 2: Accounting Appendix 3: Appraisal Appendix 4: Grimsby No.3 Fish Dock Appendix 5: Key Members of the CME’s Department in 1937/38 12. References and Notes 57 1. Sources and Acknowledgements This paper is an enlarged version of an article published in the March 2019 edition of the Journal of the Railway & Canal Historical Society. Considerable use was made of the railway records in The National Archives at Kew: the primary source of original LNER documentation. Information was obtained from Hansard, the National Records of Scotland, University of Glasgow Archives Services, National Railway Museum (NRM) and Great Eastern Railway Society (GERS). Use was made of contemporary issues of The Railway Magazine, Railway Gazette (NRM), The Economist, LNER Magazine 1927--1947 (GERS) and The Engineer. A literature review was undertaken of relevant university thesis and articles in academic journals: together with articles, papers and books written by historians and commentators on the group railway companies. 2 The -

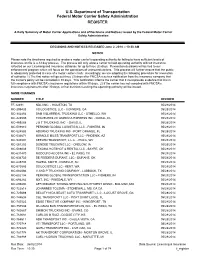

U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration REGISTER

U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration REGISTER A Daily Summary of Motor Carrier Applications and of Decisions and Notices Issued by the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration DECISIONS AND NOTICES RELEASED June 2, 2014 -- 10:30 AM NOTICE Please note the timeframe required to revoke a motor carrier's operating authority for failing to have sufficient levels of insurance on file is a 33 day process. The process will only allow a carrier to hold operating authority without insurance reflected on our Licensing and Insurance database for up to three (3) days. Revocation decisions will be tied to our enforcement program which will focus on the operations of uninsured carriers. This process will further ensure that the public is adequately protected in case of a motor carrier crash. Accordingly, we are adopting the following procedure for revocation of authority; 1) The first notice will go out three (3) days after FMCSA receives notification from the insurance company that the carrier's policy will be cancelled in 30 days. This notification informs the carrier that it must provide evidence that it is in full compliance with FMCSA's insurance regulations within 30 days. 2) If the carrier has not complied with FMCSA's insurance requirements after 30 days, a final decision revoking the operating authority will be issued. NAME CHANGES NUMBER TITLE DECIDED FF-12491 NDLI INC. - HOUSTON, TX 05/28/2014 MC-299433 VS LOGISTICS, LLC - CONYERS, GA 05/28/2014 MC-302454 SAM VILLARREAL TRUCKING LLC - OTHELLO, WA 05/28/2014 MC-428589 TRAVELERS OF AMERICA EXPRESS INC - DORAL, FL 05/28/2014 MC-469288 J & T TRUCKING, INC. -

Newspaper Index S

Watt Library, Greenock Newspaper Index This index covers stories that have appeared in newspapers in the Greenock, Gourock and Port Glasgow area from the start of the nineteenth century. It is provided to researchers as a reference resource to aid the searching of these historic publications which can be consulted, preferably by prior appointment, at the Watt Library, 9 Union Street, Greenock. Subject Entry Newspaper Date Page Sabbath Alliance Report of Sabbath Alliance meeting. Greenock Advertiser 28/01/1848 Sabbath Evening School, Sermon to be preached to raise funds. Greenock Advertiser 15/12/1820 1 Greenock Sabbath Morning Free Sabbath Morning Free Breakfast restarts on the first Sunday of October. Greenock Telegraph 21/09/1876 2 Breakfast Movement Sabbath Observation, Baillie's Orders against trespassing on the Sabbath Greenock Advertiser 10/04/1812 1 Cartsdyke Sabbath School Society, General meeting. Greenock Advertiser 26/10/1819 1 Greenock Sabbath School Society, Celebrations at 37th anniversary annual meeting - report. Greenock Advertiser 06/02/1834 3 Greenock Sabbath School Society, General meeting 22nd July Greenock Advertiser 22/07/1823 3 Greenock Sabbath School Society, Sabbath School Society - annual general meeting. Greenock Advertiser 03/04/1821 1 Greenock Sabbath School Union, 7th annual meeting - report. Greenock Advertiser 28/12/1876 2 Greenock Sabbath School Union, 7th annual meeting - report. Greenock Telegraph 27/12/1876 3 Greenock Sailcolth Article by Matthew Orr, Greenock, on observations on sail cloth and sails -

Following the Equator by Mark Twain</H1>

Following the Equator by Mark Twain Following the Equator by Mark Twain This etext was produced by David Widger FOLLOWING THE EQUATOR A JOURNEY AROUND THE WORLD BY MARK TWAIN SAMUEL L. CLEMENS HARTFORD, CONNECTICUT THE AMERICAN PUBLISHING COMPANY MDCCCXCVIII COPYRIGHT 1897 BY OLIVIA L. CLEMENS ALL RIGHTS RESERVED FORTIETH THOUSAND THIS BOOK page 1 / 720 Is affectionately inscribed to MY YOUNG FRIEND HARRY ROGERS WITH RECOGNITION OF WHAT HE IS, AND APPREHENSION OF WHAT HE MAY BECOME UNLESS HE FORM HIMSELF A LITTLE MORE CLOSELY UPON THE MODEL OF THE AUTHOR. THE PUDD'NHEAD MAXIMS. THESE WISDOMS ARE FOR THE LURING OF YOUTH TOWARD HIGH MORAL ALTITUDES. THE AUTHOR DID NOT GATHER THEM FROM PRACTICE, BUT FROM OBSERVATION. TO BE GOOD IS NOBLE; BUT TO SHOW OTHERS HOW TO BE GOOD IS NOBLER AND NO TROUBLE. CONTENTS CHAPTER I. The Party--Across America to Vancouver--On Board the Warrimo--Steamer Chairs-The Captain-Going Home under a Cloud--A Gritty Purser--The Brightest Passenger--Remedy for Bad Habits--The Doctor and the Lumbago --A Moral Pauper--Limited Smoking--Remittance-men. page 2 / 720 CHAPTER II. Change of Costume--Fish, Snake, and Boomerang Stories--Tests of Memory --A Brahmin Expert--General Grant's Memory--A Delicately Improper Tale CHAPTER III. Honolulu--Reminiscences of the Sandwich Islands--King Liholiho and His Royal Equipment--The Tabu--The Population of the Island--A Kanaka Diver --Cholera at Honolulu--Honolulu; Past and Present--The Leper Colony CHAPTER IV. Leaving Honolulu--Flying-fish--Approaching the Equator--Why the Ship Went Slow--The Front Yard of the Ship--Crossing the Equator--Horse Billiards or Shovel Board--The Waterbury Watch--Washing Decks--Ship Painters--The Great Meridian--The Loss of a Day--A Babe without a Birthday CHAPTER V.