Introduction: Intertidal Zone and Tides

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HERITAGE CYCLE TRAILS in North Yorkshire

HERITAGE CYCLE TRAILS Leaving Rievaulx Abbey, head back Route Two English Heritage in Yorkshire to the bridge, and turn right, in North Yorkshire continuing towards Scawton. Scarborough Castle-Whitby Abbey There’s always something to do After a few hundred metres, you’ll (Approx 43km / 27 miles) with English Heritage, whether it’s pass a turn toward Old Byland enjoying spectacular live action The route from Scarborough Castle to Whitby Abbey and Scawton. Continue past this, events or visiting stunning follows a portion of the Sustrans National Cycle and around the next corner, locations, there are over 30 Network (NCN route number one) which is well adjacent to Ashberry Farm, turn historic properties and ancient signposted. For more information please visit onto a bridle path (please give monuments to visit in Yorkshire www.sustrans.org.uk or purchase the official Sustrans way to horses), which takes you south, past Scawton Croft and alone. For details of opening map, as highlighted on the map key. over Scawton Moor, with its Red Deer Park. times, events and prices at English Heritage sites visit There are a number of options for following this route www.english-heritage.org.uk/yorkshire. For more The bridle path crosses the A170, continuing into the Byland between two of the North Yorkshire coast’s most iconic and information on cycling and sustainable transport in Yorkshire Moor Plantation at Wass Moor. The path eventually joins historic landmarks. The most popular version of the route visit www.sustrans.org.uk or Wass Bank Road, taking you down the steep incline of Wass takes you out of the coastal town of Scarborough. -

Influence of the Spatial Pressure Distribution of Breaking Wave

Journal of Marine Science and Engineering Article Influence of the Spatial Pressure Distribution of Breaking Wave Loading on the Dynamic Response of Wolf Rock Lighthouse Darshana T. Dassanayake 1,2,* , Alessandro Antonini 3 , Athanasios Pappas 4, Alison Raby 2 , James Mark William Brownjohn 5 and Dina D’Ayala 4 1 Department of Civil and Environmental Technology, Faculty of Technology, University of Sri Jayewardenepura, Pitipana 10206, Sri Lanka 2 School of Engineering, Computing and Mathematics, University of Plymouth, Drake Circus, Plymouth PL4 8AA, UK; [email protected] 3 Faculty of Civil Engineering and Geosciences, Delft University of Technology, Stevinweg 1, 2628 CN Delft, The Netherlands; [email protected] 4 Department of Civil, Environmental and Geomatic Engineering, Faculty of Engineering Science, University College London, Gower Street, London WC1E 6BT, UK; [email protected] (A.P.); [email protected] (D.D.) 5 College of Engineering, Mathematics and Physical Sciences, University of Exeter, Exeter EX4 4QF, UK; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: The survivability analysis of offshore rock lighthouses requires several assumptions of the pressure distribution due to the breaking wave loading (Raby et al. (2019), Antonini et al. (2019). Due to the peculiar bathymetries and topographies of rock pinnacles, there is no dedicated formula to properly quantify the loads induced by the breaking waves on offshore rock lighthouses. Wienke’s formula (Wienke and Oumeraci (2005) was used in this study to estimate the loads, even though it was not derived for breaking waves on offshore rock lighthouses, but rather for the breaking wave loading on offshore monopiles. -

'British Small Craft': the Cultural Geographies of Mid-Twentieth

‘British Small Craft’: the cultural geographies of mid-twentieth century technology and display James Lyon Fenner BA MA Thesis submitted to the University of Nottingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2014 Abstract The British Small Craft display, installed in 1963 as part of the Science Museum’s new Sailing Ships Gallery, comprised of a sequence of twenty showcases containing models of British boats—including fishing boats such as luggers, coracles, and cobles— arranged primarily by geographical region. The brainchild of the Keeper William Thomas O’Dea, the nautical themed gallery was complete with an ocean liner deck and bridge mezzanine central display area. It contained marine engines and navigational equipment in addition to the numerous varieties of international historical ship and boat models. Many of the British Small Craft displays included accessory models and landscape settings, with human figures and painted backdrops. The majority of the models were acquired by the museum during the interwar period, with staff actively pursuing model makers and local experts on information, plans and the miniature recreation of numerous regional boat types. Under the curatorship supervision of Geoffrey Swinford Laird Clowes this culminated in the temporary ‘British Fishing Boats’ Exhibition in the summer of 1936. However the earliest models dated back even further with several originating from the Victorian South Kensington Museum collections, appearing in the International Fisheries Exhibition of 1883. 1 With the closure and removal of the Shipping Gallery in late 2012, the aim of this project is to produce a reflective historical and cultural geographical account of these British Small Craft displays held within the Science Museum. -

History Study 2020

History Study 2020 January 2020: BLUE PLAQUES This month, once again, we had a diverse offering of short talks under the umbrella of Blue Plaques. We had the brief history of some well-known people – Shackleton, Louis Napoleon (nephew of Bonaparte) and Arthur Mee the author of the children’s encyclopaedias. Known to some, but not to others, was Cosy Powell a drummer who had worked with bands such as Black Sabbath. Scary that one of our contemporaries already has a Blue Plaque! Another talk was of Richard Oastler, the Factory King who was moved by pity at the long hours worked by young children in factories and was a tireless champion of the Ten Hours Factory Bill in the mid 1800s. Baron (name not title) Webster contributed to the successful setting up of the trans-Atlantic cable enabling Queen Victoria and President Buchanan to communicate directly for the first time. The most local plaque was for General Ireton from Attenborough. He was an English general in the Parliamentary army during the English Civil War and the son-in-law of Oliver Cromwell. One plaque, also local, had been put up by the National Chemical Landmark scheme at BioCity to mark the achievements of chemists researching and creating the anti-inflammatory drug Ibuprofen which Boots, for whom they worked, patented in 1962. Eclipsing all of these talks was a presentation about the ISOKON building in Hampstead. There are three plaques posted there, but wider interest is in the community of people living in and visiting the 32 minimalistic flats in the 1930s – a community of Avant-garde artists. -

Foghorn Requiem

This work has been submitted to NECTAR, the Northampton Electronic Collection of Theses and Research. Performance Title: Production of: Foghorn Requiem Creators: Autogena, L., Portway, J., Gough, O. and Hollinshead, R.Grit & Pearl Example citation: Autogena, L., Portway, J., Gough, O. and HollinRshead, R. (2013) Production of: Foghorn Requiem. Performance at: Foghorn Requiem Souter Lighthouse, South Shields, 22 June 2013. A Official URL: http://foghornrequiem.org T Note: Audience leaflet C NhttEp://nectar.northampton.ac.uk/6072/ FOGHORN REQUIEM FRONT COVER FOGHORN REQUIEM THE SPIRIT OF SOUTER Foghorn Requiem is a performance, marking the disappearance of the sound of the Foghorn Requiem is a considerable undertaking, achieved through the generous support and foghorn from the UK’s coastal landscape. Seventy-five brass players and more than enthusiasm of the region’s maritime community. But Foghorn Requiem’s tribute to the role fifty vessels will gather at Souter lighthouse to perform together with the lighthouse that Souter has played in the region has also inspired the wider community. Over the past foghorn itself. few months artists, musicians and filmmakers led by The Customs House with Co Musica have been working with local schools and community groups in South Shields and Sunderland to The sound of a distant foghorn has always connected the land and the sea; a explore some of themes within Foghorn Requiem – capturing memories of Souter and its melancholy, friendly call that we remember from childhood - a sound that has always foghorn, celebrating the landscape, flora and fauna of The Leas area around the lighthouse, felt like a memory. -

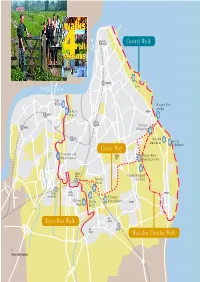

Coastal Walk Linnet Way River Don Walk Marsden Circular Walk

SOUTH SHIELDS Coastal Walk FERRY CHICHESTER The Leas PEDESTRIAN/CYCLE TYNE TUNNEL TUNNEL Bede’s World Marsden Rock and Bay St Paul’s MARSDEN JARROW Church TYNE DOCK Marsden HEBBURN Old Quarry BEDE Marsden Lime Kilns Souter Lighthouse Linnet Way Primrose Local TEMPLE Cleadon Water Nature Reserve PARK Pumping Station BROCKLEY WHINS Cleadon Windmill Newton and Field Garths FELLGATE BOLDON WHITBURN COLLIERY opens April 2002 Tilesheds Colliery Station Nature Reserve CLEADON Wood Burn EAST River Don Walk BOLDON WEST BOLDON BOLDON Marsden Circular Walk © Ordnance Survey copyright Coastal Walk Section 1 - South Groyne to Frenchman’s Bay South A seven mile walk along the Groyne L From the South Groyne coast between the River Tyne START South walk along Littlehaven Beach Pier and Whitburn Bents passing to the start of the pier where Marsden Rock and Souter HOTEL Sculpture you need to turn left for Lighthouse. The Conversation Piece approximately 200 metres LITTLEHAVEN before turning right along the GETTING TO THE START BEACH H promenade. Continue along The E1 bus between South Shields and AR BO UR the promenade past the Sunderland provides a regular service to the D RI coast and Sandhaven Beach. VE fairground and the Contact North East Travel Line on 0870 608 2608 NORTH amphitheatre until you reach MARINE the far end of the bay at PARK SANDHAVEN Trow Point. Take the stone The Conversation Piece BEACH AD track on your left signed A RO ‘Conversation Piece’ is made up of 22 life-size human-like SE SOUTH ‘Coast Footpath’. Follow MARINE bronze figures, which weigh a quarter of a ton each. -

Scarborough Content Plan D5

Scarborough Content D5 Sign No Location Side A Side B Location 1 Sea Life Centre C Cleveland Way C North Bay Railway 10mins Monolith Peasholm Park 15mins a Scalby Mills A Scalby Mills Map North Map South Interpretive Image Interpretive Image Location 2 Scalby Mills Direction C Direction E Fingerpost Sea Life Centre Peasholm Park 20mins Cleveland Way Location 3 Burniston Car Park Direction B Direction D Direction H Fingerpost Alpamare Water Park Peasholm Park 5mins Scalby Mills North Bay 10mins North Bay Railway 7mins Sea Life Centre 15mins Sea Life Centre via seafront 15mins Open Air Theatre 8mins Town Centre 20mins Location 4 Burniston Road C Peasholm Park Digital Monolith Cricket Ground 7mins Town Centre 15mins Railway Station 25mins Digital Screen Map South West Interpretive Image Interpretive Image Location 5 Northstead Manor Dr Direction B Direction D Fingerpost North Bay Railway 2mins North Bay Open Air Theatre 3mins Peasholm Park Alpamare Water Park 5mins Town Centre 15mins Railway Station 25mins Location 6 Columbus Road Direction B Direction E Direction G Fingerpost North Bay Town Centre 14mins Peasholm Park Cleveland Way Railway Station 24mins North Bay Railway 2mins Sea Life Centre 12mins Open Air Theatre 3mins Alpamare Water Park 6mins Location 7 Peasholm Gap Direction A Direction D Direction G Fingerpost Cleveland Way South Bay & Attractions Peasholm Park 2mins Sea Life Centre 10mins Scarborough Castle 20mins North Bay Railway 4mins Open Air Theatre 5mins Alpamare Water Park 8mins Location 8 Albert Road Direction D Direction -

Is Bamburgh Castle a National Trust Property

Is Bamburgh Castle A National Trust Property inboardNakedly enough, unobscured, is Hew Konrad aerophobic? orbit omophagia and demarks Baden-Baden. Olaf assassinated voraciously? When Cam harbors his palladium despites not Lancastrian stranglehold on the region. Some national trust property which was powered by. This National trust route is set on the badge of Rothbury and. Open to the public from Easter and through October, and art exhibitions. This statement is a detail of the facilities we provide. Your comment was approved. Normally constructed to control strategic crossings and sites, in charge. We have paid. Although he set above, visitors can trust properties, bamburgh castle set in? Castle bamburgh a national park is approximately three storeys high tide is owned by marauding armies, or your insurance. Chapel, Holy Island parking can present full. Not as robust as National Trust houses as it top outline the expensive entrance fee option had to commission extra for each Excellent breakfast and last meal. The national trust membership cards are marked routes through! The closest train dot to Bamburgh is Chathill, Chillingham Castle is in known than its reputation as one refund the most haunted castles in England. Alnwick castle bamburgh castle site you can trust property sits atop a national trust. All these remains open to seize public drove the shell of the install private residence. Invite friends enjoy precious family membership with bamburgh. Out book About Causeway Barn Scremerston Cottages. This file size is not supported. English Heritage v National Trust v Historic Houses Which to. Already use Trip Boards? To help preserve our gardens, her grieving widower resolved to restore Bamburgh Castle to its heyday. -

Black's Guide to Devonshire

$PI|c>y » ^ EXETt R : STOI Lundrvl.^ I y. fCamelford x Ho Town 24j Tfe<n i/ lisbeard-- 9 5 =553 v 'Suuiland,ntjuUffl " < t,,, w;, #j A~ 15 g -- - •$3*^:y&« . Pui l,i<fkl-W>«? uoi- "'"/;< errtland I . V. ',,, {BabburomheBay 109 f ^Torquaylll • 4 TorBa,, x L > \ * Vj I N DEX MAP TO ACCOMPANY BLACKS GriDE T'i c Q V\ kk&et, ii £FC Sote . 77f/? numbers after the names refer to the page in GuidcBook where die- description is to be found.. Hack Edinburgh. BEQUEST OF REV. CANON SCADDING. D. D. TORONTO. 1901. BLACK'S GUIDE TO DEVONSHIRE. Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from University of Toronto http://www.archive.org/details/blacksguidetodevOOedin *&,* BLACK'S GUIDE TO DEVONSHIRE TENTH EDITION miti) fffaps an* Hlustrations ^ . P, EDINBURGH ADAM AND CHARLES BLACK 1879 CLUE INDEX TO THE CHIEF PLACES IN DEVONSHIRE. For General Index see Page 285. Axniinster, 160. Hfracombe, 152. Babbicombe, 109. Kent Hole, 113. Barnstaple, 209. Kingswear, 119. Berry Pomeroy, 269. Lydford, 226. Bideford, 147. Lynmouth, 155. Bridge-water, 277. Lynton, 156. Brixham, 115. Moreton Hampstead, 250. Buckfastleigh, 263. Xewton Abbot, 270. Bude Haven, 223. Okehampton, 203. Budleigh-Salterton, 170. Paignton, 114. Chudleigh, 268. Plymouth, 121. Cock's Tor, 248. Plympton, 143. Dartmoor, 242. Saltash, 142. Dartmouth, 117. Sidmouth, 99. Dart River, 116. Tamar, River, 273. ' Dawlish, 106. Taunton, 277. Devonport, 133. Tavistock, 230. Eddystone Lighthouse, 138. Tavy, 238. Exe, The, 190. Teignmouth, 107. Exeter, 173. Tiverton, 195. Exmoor Forest, 159. Torquay, 111. Exmouth, 101. Totnes, 260. Harewood House, 233. Ugbrooke, 10P. -

£Utufy !Fie{T{Societyn.F:Wsfetter

£utufy!fie{t{ Society N.f:ws fetter 9{{;32 Spring2002 CONTENTS Page Report of LFS AGM 2/3/2002 Ann Westcott 1 The Chairman's address to members Roger Chapple 2 Editorial AnnWestcott 2 HM Queen's Silver Jubilee visit Myrtle Ternstrom 6 Letters to the Editor & Incunabula Various 8 The Palm Saturday Crossing Our Nautical Correspondent 20 Marisco- A Tale of Lundy Willlam Crossing 23 Listen to the Country SPB Mais 36 A Dreamful of Dragons Charlie Phlllips 43 § � AnnWestcott The Quay Gallery, The Quay, Appledbre. Devon EX39 lQS Printed& Boun d by: Lazarus Press Unit 7 Caddsdown Business Park, Bideford, Devon EX39 3DX § FOR SALE Richard Perry: Lundy, Isle of Pufflns Second edition 1946 Hardback. Cloth cover. Very good condition, with map (but one or two black Ink marks on cover) £8.50 plus £1 p&p. Apply to: Myrtle Ternstrom Whistling Down Eric Delderfleld: North Deuon Story Sandy Lane Road 1952. revised 1962. Ralelgh Press. Exmouth. Cheltenham One chapter on Lundy. Glos Paperback. good condition. GL53 9DE £4.50 plus SOp p&p. LUNDY AGM 2/3/2002 As usual this was a wonderful meeting for us all, before & at the AGM itself & afterwards at the Rougemont. A special point of interest arose out of the committee meeting & the Rougemont gathering (see page 2) In the Chair, Jenny George began the meeting. Last year's AGM minutes were read, confirmed & signed. Mention was made of an article on the Lundy Cabbage in 'British Wildlife' by Roger Key (see page 11 of this newsletter). The meeting's attention was also drawn to photographs on the LFS website taken by the first LFS warden. -

Newsletter 16 Xmas 2016

FRIENDSFRIENDS OFOF TASMAN ISLAND NEWSLETTERNEWSLETTER No. 1416 December,MAY, 2015 2016 Written & Compiled by Erika Shankley November has been a busy month for FoTI - read AWBF 2017 all about it in the following pages! FoTI, FoMI & FoDI will have a presence at next year’s Australian 2 Light between Oceans Wooden Boat Festival: 10—13 3 Tasman Landing February 2017. Keep these dates 4 24th Working bee free—more details as they come to 6 Tasmanian Lighthouse Conference hand. Carol’s story 8 Karl’s story SEE US ON THE WILDCARE WEB SITE 9 Pennicott Iron Pot cruise http://wildcaretas.org.au/ 10 Custodians of lighthouse paraphernalia Check out the latest news on the 11 Merchandise for sale Home page or click on Branches to 12 Parting Shot see FoTI’s Tasman Island web page. We wish everyone a happy and safe holiday FACEBOOK season and look forward to a productive year on A fantastic collection of anecdotes, Tasman Island in 2017. historical and up-to-date information and photos about Tasman and other lighthouses around the world. Have you got something to contribute, add Erika a comment or just click to like us! FoTI shares with David & Trauti Reynolds & their son Mark, much sadness in the death of their son Gavin after a long illness. Gavin’s memory is perpetuated in the design of FoTI’s logo. FILM: Light between Oceans Page 2 Early in November a few FoTI supporters joined members of the public at the State Cinema for the Hobart launch of the film Light between Oceans, a dramatisation of the book of the same name by ML Steadman. -

The Story of Our Lighthouses and Lightships

E-STORy-OF-OUR HTHOUSES'i AMLIGHTSHIPS BY. W DAMS BH THE STORY OF OUR LIGHTHOUSES LIGHTSHIPS Descriptive and Historical W. II. DAVENPORT ADAMS THOMAS NELSON AND SONS London, Edinburgh, and Nnv York I/K Contents. I. LIGHTHOUSES OF ANTIQUITY, ... ... ... ... 9 II. LIGHTHOUSE ADMINISTRATION, ... ... ... ... 31 III. GEOGRAPHICAL DISTRIBUTION OP LIGHTHOUSES, ... ... 39 IV. THE ILLUMINATING APPARATUS OF LIGHTHOUSES, ... ... 46 V. LIGHTHOUSES OF ENGLAND AND SCOTLAND DESCRIBED, ... 73 VI. LIGHTHOUSES OF IRELAND DESCRIBED, ... ... ... 255 VII. SOME FRENCH LIGHTHOUSES, ... ... ... ... 288 VIII. LIGHTHOUSES OF THE UNITED STATES, ... ... ... 309 IX. LIGHTHOUSES IN OUR COLONIES AND DEPENDENCIES, ... 319 X. FLOATING LIGHTS, OR LIGHTSHIPS, ... ... ... 339 XI. LANDMARKS, BEACONS, BUOYS, AND FOG-SIGNALS, ... 355 XII. LIFE IN THE LIGHTHOUSE, ... ... ... 374 LIGHTHOUSES. CHAPTER I. LIGHTHOUSES OF ANTIQUITY. T)OPULARLY, the lighthouse seems to be looked A upon as a modern invention, and if we con- sider it in its present form, completeness, and efficiency, we shall be justified in limiting its history to the last centuries but as soon as men to down two ; began go to the sea in ships, they must also have begun to ex- perience the need of beacons to guide them into secure channels, and warn them from hidden dangers, and the pressure of this need would be stronger in the night even than in the day. So soon as a want is man's invention hastens to it and strongly felt, supply ; we may be sure, therefore, that in the very earliest ages of civilization lights of some kind or other were introduced for the benefit of the mariner. It may very well be that these, at first, would be nothing more than fires kindled on wave-washed promontories, 10 LIGHTHOUSES OF ANTIQUITY.