An Ex-Post Cost Benefit Analysis of Italian High Speed Train, Five Years After

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Diapositiva 1

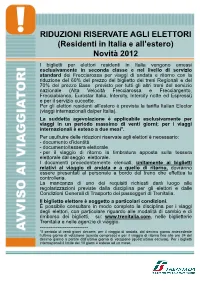

RIDUZIONI RISERVATE AGLI ELETTORI (Residenti in Italia e all’estero) Novità 2012 I biglietti per elettori residenti in Italia vengono emessi esclusivamente in seconda classe e nel livello di servizio standard dei Frecciarossa per viaggi di andata e ritorno con la riduzione del 60% del prezzo del biglietto dei treni Regionali e del 70% del prezzo Base previsto per tutti gli altri treni del servizio nazionale (Alta Velocità Frecciarossa e Frecciargento, Frecciabianca, Eurostar Italia, Intercity, Intercity notte ed Espressi) e per il servizio cuccette. Per gli elettori residenti all’estero è prevista la tariffa Italian Elector (viaggi internazionali da/per Italia). La suddetta agevolazione è applicabile esclusivamente per viaggi in un periodo massimo di venti giorni; per i viaggi internazionali è esteso a due mesi*. Per usufruire delle riduzioni riservate agli elettori è necessario: - documento d’identità - documento/tessera elettorale - per il viaggio di ritorno la timbratura apposta sulla tessera elettorale dal seggio elettorale. I documenti precedentemente elencati, unitamente ai biglietti relativi al viaggio di andata e a quello di ritorno, dovranno essere presentati al personale a bordo del treno che effettua la controlleria. La mancanza di uno dei requisiti richiesti darà luogo alle regolarizzazioni previste dalla disciplina per gli elettori e dalle Condizioni Generali di Trasporto dei passeggeri di Trenitalia. Il biglietto elettore è soggetto a particolari condizioni. È possibile consultare in modo completo la disciplina per i viaggi degli elettori, con particolare riguardo alle modalità di cambio e di rimborso dei biglietti, su: www.trenitalia.com, nelle biglietterie Trenitalia e nelle agenzie di viaggio. --------------------------- *Il periodo di venti giorni decorre, per il viaggio di andata, dal decimo giorno antecedente l’ultimo giorno di votazione (questo compreso) e per il viaggio di ritorno fino alle ore 24 del decimo giorno a partire dall’ultimo giorno di votazione (quest’ultimo escluso). -

Costs and Demand of High Speed Rail in Italy and Spain

World Conference on Transport Research - WCTR 2016 Shanghai. 10-15 July 2016 Delusions of success: costs and demand of high speed rail in Italy and Spain Paolo Beria1a, Daniel Albalateb, Raffaele Grimaldia, Germà Belb a Department of Architecture and Urban Studies (DAStU), Politecnico di Milano, Italy b Dep. Política Econòmica, Universitat de Barcelona, Spain Abstract Mismatches between forecasted and actual costs and traffic figures are common in transport investments, especially in large scale ones, and so are delusions on future demand. High-speed rail project are often among the worst practices for cost overruns and demand overestimation, even where traffic figures may tell a history of apparent success. In the paper, we analyse two significant cases of delusion of success, namely Italian and Spanish HSR programmes. The Italian one shows excellent demand performances, but is among the continental worst cases for construction costs. The Spanish one, recognised worldwide as one of the most successful cases, is the one where potential demand estimations was systematically neglected and the planned network appears largely out-of-scale compared to actual traffic. The two cases show that the core of the problem does not lay in the wrong estimations of costs and demand, but on deliberate choices of overinvestment, overdesign and overquality. © 2017 The Authors. Published by Elsevier B.V. Peer-review under responsibility of WORLD CONFERENCE ON TRANSPORT RESEARCH SOCIETY. Keywords: High-speed rail, megaprojects, Italy, Spain, cost overrun, demand estimation, optimism bias 1 Corresponding author. Tel.: +39-02-2399-5424; fax: +39-02-2399-5435. E-mail address: [email protected] © 2017 The Authors 2 Beria, Albalate, Grimaldi, Bel / Transportation Research Procedia 00 (2017) 000–000 1. -

Lorem Ipsum Dolor Sit Amet (Titolo)

Comunicato Stampa IN 3 MESI PIÙ DI 5MILA AMICI A QUATTRO ZAMPE SULLE FRECCE lanciata lo scorso luglio, l’iniziativa permette di trasportare sulle Frecce il proprio cane di qualsiasi taglia record di gradimento per il Frecciarossa che supera il 96%, a 95% il Frecciargento Roma, 16 ottobre 2012 Cinquemila biglietti venduti, in poco più di due mesi, per i cani di media e grossa taglia in viaggio sulle Frecce di Trenitalia. L’iniziativa, lanciata lo scorso 25 luglio, ha aperto le porte delle Frecce di Trenitalia anche ai cani di taglia grande. Da allora, quasi un treno su cinque ha ospitato a bordo un cane. Il successo nei numeri trova riscontro anche nell’alto gradimento espresso dalla clientela e ha permesso di consolidare il progetto mettendolo definitivamente a regime da inizio ottobre. Gli amici a quattro zampe sono ammessi su Frecciarossa, Frecciargento, Frecciabianca ed Eurostar Italia, oltre che sui treni dove erano già previsti (Intercity e Notte), sia in 1a che in 2a classe e nei livelli di servizio Business e Standard. La soddisfazione per il servizio offerto dalle Frecce di Trenitalia migliora non solo in relazione alle novità relative all’accesso dei cani. I risultati dell’ultima ricerca di customer satisfaction mostrano tutti gli indici in decisa crescita. In particolare, il Frecciarossa si attesta al 96,1% di clienti soddisfatti del viaggio nel suo complesso, massimo storico, e registra una crescita di 3 punti percentuali fra i così detti “deliziati”, ossia fra coloro che attribuiscono voti pari a 8 e 9. Il Frecciargento raggiunge il 95% di viaggiatori soddisfatti, 2 punti percentuali in più rispetto al 2011. -

Eurail Group G.I.E

Eurail Group G.I.E. Eurail Group G.I.E. Eurail Group G.I.E. Eurail Group G.I.E. Eurail Group G.I.E. Eurail Group G.I.E. Eurosender Benefit: Pass holders benefit from a 20% discount on the Eurosender online platform when placing an order to send a package or parcel. Benefit code: RAIL20 Info: Follow the steps below to redeem the Benefit: 1. Visit Eurosender website: www.eurosender.com 2. Choose your to and from countries from the list. 3. Select the number of packages or parcels to be sent and click ‘NEXT’. 4. Fill in the order form. 5. Insert the Benefit code RAIL20 in the box “discount code”. The new price and amount of discount will be displayed. 6. Select the payment method and insert your payment details. 7. Receive order confirmation. For any problems or questions regarding your order or the service, Eurosender customer support department is available on Tel: +44 (0)20 3318 3600 or by email at [email protected]. Please note: The Benefit code is valid only for a single user. The code has no expiration date and it can be transferrable. This Benefit is valid only for standard shipping orders. Benefit: Eurail and Interrail Pass holders benefit from 20% off Stasher Luggage Storage. Book online to store your bags safely while you explore the city – all across Europe. Use EURAIL20 or INTERRAIL20 for 20% off the entire booking (including insurance). Info: Follow the steps below to redeem the Benefit 1. Visit Stasher.com 2. Enter the location where you wish to store your bag 3. -

Con Il Cane Sulle Frecce Di Redazione

da Brevi ferroviarie del 20 luglio 2012 Con il cane sulle Frecce di Redazione ROMA - I cani tornano a bordo dei treni. Dal 25 luglio sarà infatti possibile viaggiare con il proprio cane al seguito a bordo di Frecciarossa, Frecciargento, Frecciabianca ed Eurostar Italia (oltre ai treni dove già attualmente è consentito), sia in 1a che in 2a classe come in Business e Standard, ad eccezione dei livelli Executive, Premium, Area del Silenzio e salottini. Questo grazie ad un accordo quadro tra Trenitalia e Federazione Italiana Associazioni Diritti Animali e Ambiente, siglato oggi a bordo di un ETR.500 Frecciarossa a Roma Termini da Mauro Moretti e l'Onorevole Michela Vittoria Brambilla. 1. Mauro Moretti amministratore del Gruppo Ferrovie dello Stato Italiane e l'Onorevole Michela Vittoria Brambilla, presidente nonché fondatrice d1ella LEga Italiana per la Difesa degli Animali (LEIDA). (Foto David Campione, 20 luglio 2012) Per salire a bordo con il proprio amico a quattro zampe, il proprietario dovrà acquistare un biglietto prezzo Base (previsto per il treno utilizzato) ridotto del 50%. Prima del viaggio sarà necessario disporre di museruola e guinzaglio, certificato di iscrizione all'anagrafe canina (per i cittadini stranieri l'apposito passaporto del cane) e libretto sanitario. Fanno eccezione i cani guida per non vedenti, che invece continueranno a viaggiare su tutti i treni gratuitamente e senza alcun obbligo. Il biglietto per il trasporto del cane può essere acquistato nelle biglietterie e nelle agenzie abilitate, collegandolo a quello dell'accompagnatore ed è valido solo se utilizzato per il treno ed il giorno prenotato. Gli animali di piccola taglia, custoditi nell'apposito trasportino, continueranno a poter viaggiare gratuitamente su tutti i treni del gruppo FS, così come avviene già oggi. -

High Speed Railway Project Development and Regional Accessibility Improvement: the First Experience in India

FACULTY OF CIVIL AND INDUSTRIAL ENGINEERING Master Degree in Transport System Engineering Thesis High Speed Railway Project Development and Regional Accessibility Improvement: The First Experience in India Supervisor: Candidate: Prof. Eng. Antonio Musso Amal Kuzhiparambil Purushothaman Co-Supervisor: N° 1722321 Dr. Eng. Cristiana Piccioni Academic Year 2018/2019 2 Table of contents Summary 1. Introduction 1.1 Study purpose 1.2 Research background 1.3 Research methodology 1.4 Key issues 2. The Reference framework 2.1 Definition of high-speed rail 2.2 HSR benefits 2.3 HS Rail around the world 2.3.1 Japan 2.3.2 Italy 2.3.3 France 2.3.4 Germany 2.3.5 Spain 2.3.6 China 3. The accessibility concept 3.1 Definition of accessibility 3.2 Accessibility indicators 3.3 A basic benchmarking exercise 4. Accessibility and HSR projects: an insight into international experiences 4.1 The Madrid-Barcelona HSR case study, Spain 4.2 The China HSR case study 4.3 The Seoul HSR case study, Korea 4.4 Brisbane - Melbourne proposed HSR, Australia 5. Building an accessibility indicators framework 5.1 Identification of Accessibility indicators 5.2 A selection of accessibility indicators 5.2.1 Weighted average travel times (Location indicator) 5.2.2 Economic potential 3 5.2.3 Daily accessibility indicator 5.2.4 Economic accessibility 6. Pilot study: the Mumbai – Ahmedabad HSR project 6.1 HSR project background 6.1.1 Necessity of HSR System in India 6.2 Major cities affected by the project 6.2.1 Mumbai 6.2.2 Surat 6.2.3 Vadodara 6.2.4 Ahmedabad 6.3 HSR Project overview 6.3.1 Basic characteristics 6.3.2 Stations 6.3.3 Train operation plans 6.4 Accessibility assessment 6.4.1 Calculation and evaluation of indicators 6.4.2 Weighted average travel times (location indicator) 6.4.3 Economic potential 6.4.4 Daily accessibility indicator 6.4.5 Economic indicator 7. -

Treni Etr 500 Frecciarossa

Evaristo Principe TRENI ITALIANI ETR 500 FRECCIAROSSA GENOVA 10 LUGLIO 2014 Buongiorno a tutti Evaristo Principe TRENI ITALIANI ETR 500 FRECCIAROSSA Evaristo Principe TRENI ITALIANI ETR 500 FRECCIAROSSA Evaristo Principe TRENI ITALIANI ETR 500 FRECCIAROSSA TRENITALIA Evaristo Principe TRENI ITALIANI ETR 500 FRECCIAROSSA Inizio dell’Alta Velocità/Alta Capacità (AV / AT) Uno dei problemi maggiori che ha interessato, fin dall’inizio, tutte le Società che si sono occupate di esercizio ferroviario, è stato quello di diminuire i tempi di percorrenza dei treni ancora più dell’aumento delle prestazioni. La necessità di una comunicazione veloce si presentò fin dall’inizio del 1871, subito dopo la proclamazione di Roma Capitale del Regno. I primi studi di una nuova ferrovia di grande comunicazione iniziarono appunto nel 1871 per un collegamento tra Roma e Napoli. Numerosi furono gli studi negli anni successivi, a questi però non fecero subito seguito progetti concreti. Questa necessità venne però impostata, con precise direttive e solide basi, solamente nel 1901 con la istituzione delle Commissione Reale per lo studio delle Ferrovie Complementari, commissione che si è occupata anche della linea diretta Roma – Napoli, che già allora si chiamò “Direttissima”, e già a giugno del 1902 è stato presentato un progetto di massima. I primi progetti esecutivi per l’appalto dei lavori vennero compilati dall’allora Servizio Costruzioni dell’Amministrazione delle Ferrovie. L’inizio dei lavori è avvenuto il luglio 1905 in occasione dell’anniversario dei 100 anni -

Nuovo Orario Trenitalia 2016: Aumentano Le Frecce

da Brevi ferroviarie del 30 novembre 2015 Nuovo orario Trenitalia 2016: aumentano le Frecce Comunicato stampa Gruppo FS Ancora più Frecce Trenitalia con il nuovo orario invernale 2016, al via il prossimo 13 dicembre. Cresce il numero dei nuovissimi Frecciarossa 1000 in circolazione e aumentano i collegamenti con le Frecce, anche in vista del Giubileo della Misericordia. Tutti i treni a percorrenza nazionale e internazionale del nuovo orario sono già acquistabili sui canali di vendita Trenitalia, insieme a promozioni e offerte speciali ideate ad hoc per il periodo natalizio e invernale. Ottantasei Frecciarossa al giorno tra Roma e Milano Con quattro treni in più al giorno salgono a ottantasei i Frecciarossa tra Roma e Milano. Di questi 42 uniscono direttamente le due città in meno di tre ore: uno ogni ora dalle 6 alle 20 con aumento dell'offerta ogni mezz'ora nelle fasce di maggiore richiesta dai clienti. Sono quindi 28 Frecciarossa senza fermate intermedie tra Colosseo e Madonnina, 12 con unica fermata a Bologna e due a Reggio Emilia AV. Gli altri 44 Frecciarossa, che completano l'offerta, hanno fermate anche a Firenze e a Bologna. Con una breve sosta a Tiburtina, Milano Porta Garibaldi e Rogoredo alcuni Frecciarossa collegano anche le altre aree delle due città. Nuovi Frecciarossa 1000 in servizio Nuovi Frecciarossa 1000 in servizio. Salgono a 28 (sei in più) al giorno i viaggi realizzati con il nuovo supertreno di Trenitalia. Oltre a Milano e Roma le corse dei Frecciarossa 1000 interessano anche le stazioni di Napoli, Bologna e Torino. Ma i vantaggi del Frecciarossa vanno oltre il network AV Torino - Salerno: aumentano da 8 a 14 (sei in più) al giorno i Frecciarossa che collegano Roma con Padova e Venezia. -

2018 19 Orariotimetable

IN TRENO Aggiornato al xx xx xx ORARIOTIMETABLE 2018 19 DIGITALE LE FRECCE 9 Dicembre - 8 Giugno th th 9 December - 8 June QUADRI ORARIO AGGIORNATI al 1/04/2019 © FS Italiane | ADVERTISING - © Adobe Stock/***** PER TENERTI AGGIORNATO FOR LATEST UPDATES COMINCIA DA QUI, SCEGLI TRENITALIA! STARTS FROM TRENITALIA! Gentile Cliente, Dear Customer, a seguito di alcune segnalazioni e aggiornamenti riguardanti following a few reports and updates to the railway offer valid until l'offerta ferroviaria valida fino all'8 giugno 2019, la linea the 8th June 2019, the editorial Train saw fit to upgrade, only as editoriale In Treno ha ritenuto opportuno aggiornare, solo per regards the timetable that, this digital edition. quanto concerne i quadri orario, la presente edizione digitale. The timetable information you find in this publication is valid from Le informazioni orario che trovi in questa pubblicazione hanno the 1st April, while those relating to the editorial sections have not validità dal 1 aprile, mentre quelle relative alle sezioni redazionali changed with respect to what was reported in the previous edition non hanno subito modifiche rispetto a quanto riportato nella of December 2018. precedente edizione di dicembre 2018. We are waiting for you on board, good consultation and a good Ti aspettiamo a bordo, buona consultazione e buon viaggio con trip with Trenitalia! Trenitalia! pagina 1 dic2018 new NEW.pdf 1 10/01/2019 12:11:39 IL TUO VIAGGIO IN TRENO YOUR TRAIN JOUNEY COMINCIA DA QUI, SCEGLI TRENITALIA! STARTS FROM TRENITALIA! Gentile Cliente, Dear Customer, questa pubblicazione della linea editoriale In Treno ti guida alla this brochure details the 280 Frecce trains by Trenitalia, which from the 9th scoperta dell’offerta Trenitalia, che dal 9 dicembre 2018 prevede December 2018 travel along the Belpaese. -

The Uneasy Progress of High-Speed Trains and Railway Liberalization

10 AND YET IT MOVES : THE UNE A S Y PROGRESS OF HI GH -SP EED TR ai NS A ND Rai LW ay LIBERALIZATION Mauro Tebaldi On 5 December 2009, Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi, together with the director-general of the Ferrovie dello Stato (FS), Mauro Moretti, officially opened the new high-speed/high-capacity railway line, link- ing Turin, Milan, and Salerno at the central station in Milan.1 The work, which had taken almost 40 years to complete, had involved the laying of just less than 1,000 kilometers of track that is specially designed to carry high-speed trains. The following day, the high-speed train service provided by Trenitalia began operating on the line with the latest ETR (Elettro Treno Rapido) 500 Frecciarossa and ETR 600 Frecciargento trains. The year 2010, therefore, marked the official operational start of the project that had first been drawn up by FS in the early 1960s with the aim of providing high-speed rail links for the main Italian cities along a north-south axis in response to two clear challenges—the growing competition from airlines2 and an increasing preference for road use.3 Although 2010 marks an important stage in the development of high-speed/high-capacity railways in Italy, it should be pointed out that it represents only a partial completion of what had been a long- standing and somewhat drawn-out policy that had been characterized by infighting, vetoes, poor planning strategies, judicial investigations, financial problems, and bitter disputes within the three main areas Notes for this chapter begin on page 257. -

Il Caso Veloci, Verso Il Futuro

31a EDIZIONE PREMIO MARKETING SIM 2019 IL CASO VELOCI, VERSO IL FUTURO Vincere la concorrenza nella mobilità rapida, sostenibile e connessa INDICE 1. Il brand Frecciarossa nel tempo 2. La mobilità: un mercato in movimento 3. L’Alta Velocità in Italia e Europa 3.1. Il lancio dell’Alta Velocità in Italia 3.2. I motivi di scelta del Cliente 4. Il marketing nei servizi di mobilità ferroviaria 4.1. Il Prodotto: la flotta, l’offerta e il network delle Frecce 4.1.1 Il cliente AV 4.2. Il pricing e revenue management 4.3. La comunicazione 4.4. I canali di distribuzione LA SFIDA 2019: Il problema 5. Gli obiettivi da raggiungere 5.1. Cosa si vince? 5.2. Materiali a disposizione 1 1. Il brand Frecciarossa nel tempo Quella di Frecciarossa è la storia di un brand moderno e dinamico che dal suo lancio ad oggi è evoluto lungo una traiettoria di brand identity precisa e coerente (figura 1) rispetto sia alla maggiore sofisticazione della domanda di mobilità sia alle più intense pressioni competitive dovute all’ingresso di nuovi player, affermandosi come il brand Alta Velocità più noto (89,2%). Figura 1. L’evoluzione del brand Frecciarossa Fonte: dati aziendali Il lancio del brand Frecciarossa nel 2008 rappresenta una chiara scelta aziendale di dare l’avvio ad un’era nuova dell’Alta Velocità sostituendo definitivamente l’idea ed il brand ES* Eurostar Italia, emblema dei primi collegamenti AV italiani, associato a categorie di servizio, prestazioni ed immaginario di fruizione superati. La proposta del brand Frecciarossa si inquadra nel ridisegno delle strategie di marketing attuate da Trenitalia con l’introduzione dell’Alta Velocità nel 2005 per la definizione di un’offerta di valore articolata e in grado di soddisfare esigenze espresse e latenti di diversi segmenti di clientela, sia in relazione al servizio essenziale che ai peripheral di prodotto. -

“On the Modal Shift from Motorway to High-Speed Rail: Evidence from Italy”

Institut de Recerca en Economia Aplicada Regional i Pública Document de Treball 2019/10 1/35 pág. Research Institute of Applied Economics Working Paper 2019/10 1/35 pág. “On the modal shift from motorway to high-speed rail: evidence from Italy” Mattia Borsati and Daniel Albalate 4 WEBSITE: www.ub.edu/irea/ • CONTACT: [email protected] The Research Institute of Applied Economics (IREA) in Barcelona was founded in 2005, as a research institute in applied economics. Three consolidated research groups make up the institute: AQR, RISK and GiM, and a large number of members are involved in the Institute. IREA focuses on four priority lines of investigation: (i) the quantitative study of regional and urban economic activity and analysis of regional and local economic policies, (ii) study of public economic activity in markets, particularly in the fields of empirical evaluation of privatization, the regulation and competition in the markets of public services using state of industrial economy, (iii) risk analysis in finance and insurance, and (iv) the development of micro and macro econometrics applied for the analysis of economic activity, particularly for quantitative evaluation of public policies. IREA Working Papers often represent preliminary work and are circulated to encourage discussion. Citation of such a paper should account for its provisional character. For that reason, IREA Working Papers may not be reproduced or distributed without the written consent of the author. A revised version may be available directly from the author. Any opinions expressed here are those of the author(s) and not those of IREA. Research published in this series may include views on policy, but the institute itself takes no institutional policy positions.