The Struggle Over Secularism Andits Implications for Politics And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Democratic Transition in Anglophone West Africa Byjibrin Ibrahim

Democratic Transition in Anglophone West Africa Democratic Transition in Anglophone West Africa Jibrin Ibrahim Monograph Series The CODESRIA Monograph Series is published to stimulate debate, comments, and further research on the subjects covered. The Series will serve as a forum for works based on the findings of original research, which however are too long for academic journals but not long enough to be published as books, and which deserve to be accessible to the research community in Africa and elsewhere. Such works may be case studies, theoretical debates or both, but they incorporate significant findings, analyses, and critical evaluations of the current literature on the subjects in question. Author Jibrin Ibrahim directs the International Human Rights Law Group in Nigeria, which he joined from Ahmadu Bello University where he was Associate Professor of Political Science. His research interests are democratisation and the politics of transition, comparative federalism, religious and ethnic identities, and the crisis in social provisioning in Africa. He has edited and co-edited a number of books, among which are Federalism and Decentralisation in Africa (University of Fribourg, 1999), Expanding Democratic Space in Nigeria (CODESRIA, 1997) and Democratisation Processes in Africa, (CODESRIA, 1995). Democratic Transition in Anglophone West Africa © Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa 2003, Avenue Cheikh Anta Diop Angle Canal IV, BP. 3304, Dakar, Senegal. Web Site: http://www.codesria.org CODESRIA gratefully -

PROVISIONAL LIST.Pdf

S/N NAME YEAR OF CALL BRANCH PHONE NO EMAIL 1 JONATHAN FELIX ABA 2 SYLVESTER C. IFEAKOR ABA 3 NSIKAK UTANG IJIOMA ABA 4 ORAKWE OBIANUJU IFEYINWA ABA 5 OGUNJI CHIDOZIE KINGSLEY ABA 6 UCHENNA V. OBODOCHUKWU ABA 7 KEVIN CHUKWUDI NWUFO, SAN ABA 8 NWOGU IFIONU TAGBO ABA 9 ANIAWONWA NJIDEKA LINDA ABA 10 UKOH NDUDIM ISAAC ABA 11 EKENE RICHIE IREMEKA ABA 12 HIPPOLITUS U. UDENSI ABA 13 ABIGAIL C. AGBAI ABA 14 UKPAI OKORIE UKAIRO ABA 15 ONYINYECHI GIFT OGBODO ABA 16 EZINMA UKPAI UKAIRO ABA 17 GRACE UZOME UKEJE ABA 18 AJUGA JOHN ONWUKWE ABA 19 ONUCHUKWU CHARLES NSOBUNDU ABA 20 IREM ENYINNAYA OKERE ABA 21 ONYEKACHI OKWUOSA MUKOSOLU ABA 22 CHINYERE C. UMEOJIAKA ABA 23 OBIORA AKINWUMI OBIANWU, SAN ABA 24 NWAUGO VICTOR CHIMA ABA 25 NWABUIKWU K. MGBEMENA ABA 26 KANU FRANCIS ONYEBUCHI ABA 27 MARK ISRAEL CHIJIOKE ABA 28 EMEKA E. AGWULONU ABA 29 TREASURE E. N. UDO ABA 30 JULIET N. UDECHUKWU ABA 31 AWA CHUKWU IKECHUKWU ABA 32 CHIMUANYA V. OKWANDU ABA 33 CHIBUEZE OWUALAH ABA 34 AMANZE LINUS ALOMA ABA 35 CHINONSO ONONUJU ABA 36 MABEL OGONNAYA EZE ABA 37 BOB CHIEDOZIE OGU ABA 38 DANDY CHIMAOBI NWOKONNA ABA 39 JOHN IFEANYICHUKWU KALU ABA 40 UGOCHUKWU UKIWE ABA 41 FELIX EGBULE AGBARIRI, SAN ABA 42 OMENIHU CHINWEUBA ABA 43 IGNATIUS O. NWOKO ABA 44 ICHIE MATTHEW EKEOMA ABA 45 ICHIE CORDELIA CHINWENDU ABA 46 NNAMDI G. NWABEKE ABA 47 NNAOCHIE ADAOBI ANANSO ABA 48 OGOJIAKU RUFUS UMUNNA ABA 49 EPHRAIM CHINEDU DURU ABA 50 UGONWANYI S. AHAIWE ABA 51 EMMANUEL E. -

Con Vol 27. No 1. 2020.Cdr

Vol. 27. No. 1 Of Vol. 27 No.1 2020 Journal of Curriculum Organization of Nigeria (CON) ISSN: 0189-9465 i Vol. 27. No. 1 NIGERIAN JOURNAL OF CURRICULUM STUDIES EDITORIAL BOARD (ISSN 0189 - 9465) Editor Professor Uchenna Nzewi Faculty of Education University of Nigeria, Nsukka Associate Editors Faculty of Education University of Nigeria, Nsukka Professor G. C. Offorma Professor I. M. Kalu Faculty of Education University of Calabar, Calabar Professor Nnenna Kanno Faculty of Education, Michael Okpara Univ., Umudike. Professor Abeke Adesanya Faculty of Education Olabisi Onabanjo University Ago-Iwoye, Ogun State Professor Akon E. O. Esu Faculty of Education University of Calabar, Calabar Professor A. E. Udosen Faculty of Education University of Uyo, Uyo Editorial Advisers: Professor P. A. I. Obanya 10 Ladoke Akintola Avenue New Bodija, Ibadan, P. O. Box 7112, Secretariat, Agodi, Ibadan Professor Peter Lassa Faculty of Education University of Jos Professor U. M. O. Ivowi Foremost Educational Services Limited Lagos Professor R. D. Olarinoye College of Science and Engineering, Landmark University, Omu-Aran, Kwara, State All articles for publication should be sent to: Professor Uchenna M. Nzewi Department of Science Education, Faculty of Education, University of Nigeria, Nsukka. www. con.org.ng ii Vol. 27. No. 1 This Journal is a forum for the dissemination of research findings and reports on curriculum development, implementation, innovation, diversification and renewal. In developing a curriculum, it is often necessary to use the experiences of the past and present demands as well as practices within and outside the system to design a desirable educational programme. Problems and issues in comparative education are relevant in shaping the curriculum. -

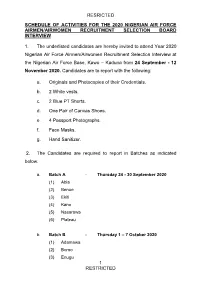

Resricted 1 Restricted Schedule of Activities For

RESRICTED SCHEDULE OF ACTIVITIES FOR THE 2020 NIGERIAN AIR FORCE AIRMEN/AIRWOMEN RECRUITMENT SELECTION BOARD INTERVIEW 1. The underlisted candidates are hereby invited to attend Year 2020 Nigerian Air Force Airmen/Airwomen Recruitment Selection Interview at the Nigerian Air Force Base, Kawo – Kaduna from 24 September - 12 November 2020. Candidates are to report with the following: a. Originals and Photocopies of their Credentials. b. 2 White vests. c. 2 Blue PT Shorts. d. One Pair of Canvas Shoes. e. 4 Passport Photographs. f. Face Masks. g. Hand Sanitizer. 2. The Candidates are required to report in Batches as indicated below: a. Batch A - Thursday 24 - 30 September 2020 (1) Abia (2) Benue (3) Ekiti (4) Kano (5) Nasarawa (6) Plateau b. Batch B - Thursday 1 – 7 October 2020 (1) Adamawa (2) Borno (3) Enugu 1 RESTRICTED RESRICTED (4) Katsina (5) Niger (6) Rivers c. Batch C - Thursday 8 – 14 October 2020 (1) Akwa Ibom (2) Cross River (3) Gombe (4) Kebbi (5) Ogun (6) Sokoto d. Batch D - Thursday 15 – 21 October 2020 (1) Anambra (2) Delta (3) Imo (4) Kogi (5) Ondo (6) Taraba e. Batch E - Thursday 22 – 28 October 2020 (1) Bauchi (2) Ebonyi (3) Jigawa (4) Kwara (5) Osun (6) Yobe f. Batch F - Thursday 29 October – 5 November 2020 (1) Bayelsa (2) Edo (3) Kaduna 2 RESTRICTED RESRICTED (4) Lagos (5) Oyo (6) Zamfara (7) FCT Note: Face masks are to be worn and other COVID-19 preventive measures are to be strictly observed throughout the exercise. SIGNED MAHMOUD EL-HAJI AHMED Air Vice Marshal for Chief of the Air Staff 3 RESTRICTED RESTRICTED SHORTLISTED -

S/No Registration Number Candidate Full Name State

LIST OF SUCCESSFUL CANDIDATES FOR PHYSICAL SCREENING 2018 RECRUITMENT EXERCISE FOR CONSTABLES (ADAMAWA STATE) REGISTRATION LOCAL S/NO NUMBER CANDIDATE FULL NAME STATE GOVERNMENT GENDER 1 ADM/PC/1001000 EVANS LUTONO ADAMAWA DEMSA MALE 2 ADM/PC/1001918 IBRAHIM NZADON YAHAYA ADAMAWA DEMSA MALE 3 ADM/PC/1004500 JULIUS NUMBAMI ELIHU ADAMAWA DEMSA MALE 4 ADM/PC/1006276 KADMIEL PUSHITAYANG ADAMAWA DEMSA MALE 5 ADM/PC/1006739 MUHAMMAD JAFAR A ADAMAWA DEMSA MALE 6 ADM/PC/1007623 WILSON MISHINARAM ADAMAWA DEMSA MALE 7 ADM/PC/1010283 AMOS LINUS ADAMAWA DEMSA MALE 8 ADM/PC/1015520 SIMON SUNDAY ADAMAWA DEMSA MALE 9 ADM/PC/1022435 ZANYE PANASOM ADAMAWA DEMSA MALE 10 ADM/PC/1024856 RAPHAEL RAYON ADAMAWA DEMSA MALE 11 ADM/PC/1025782 MUSA PAUL ADAMAWA DEMSA MALE 12 ADM/PC/1026355 DENHAM HASSAN ADAMAWA DEMSA MALE 13 ADM/PC/1026514 SAMSON GODIYA ADAMAWA DEMSA FEMALE 14 ADM/PC/1029100 GABRIEL TAPWARI ADAMAWA DEMSA MALE 15 ADM/PC/1032470 SAMSON GODIYA ADAMAWA DEMSA FEMALE 16 ADM/PC/1034069 JAMES JIMMY ADAMAWA DEMSA MALE 17 ADM/PC/1036334 DIMAS MURTE BWALMO ADAMAWA DEMSA MALE 18 ADM/PC/1036747 SURAM DAPIKYAM ADAMAWA DEMSA MALE 19 ADM/PC/1039861 GABRIEL CHAMATAM TAPWARI ADAMAWA DEMSA MALE 20 ADM/PC/1044992 ANTIBAS ISHAKU AMOS ADAMAWA DEMSA MALE 21 ADM/PC/1046404 PHINEAS EMMANUEL ADAMAWA DEMSA MALE 22 ADM/PC/1048112 JESSY PETER MANJI ADAMAWA DEMSA MALE 23 ADM/PC/1052092 JULIUS JIL JAMEEL ADAMAWA DEMSA MALE SUCCESSFUL LIST FOR PHYSICAL SCREENING 2018 CONSTABLES RECRUITMENT EXERCISE 5/4/2018 1/271 LIST OF SUCCESSFUL CANDIDATES FOR PHYSICAL SCREENING 2018 RECRUITMENT -

Programmes in Nigeria

Nicholas Ibeawuchi Omenka - BETH 10: 21 The Winds of Change: The Church and the Transition to Civil Rule Programmes in Nigeria By Nicholas Ibeawuchi Omenka Abstract For more than a decade, military disengagement from African politics has been at the centre stage ofpolitical debate on the continent. While several African countries have recorded significant successes in this regard, the Nigerian experience has been one of a long succession of disappointments. This paper examines the various transition to civil rule programmes in Nigeria from. the perspective of the Church's reaction to them. It primarily establishes a synthesis of the various communiques and pronouncements of the Church leaders on the transition programmes and situates this within the Church's social teachings and the global insistence on human rights and free choice of governance. A central observation from this study is the fact that the transition programmes have transformed the otherwise politically passive Church leaders to a vocal and active political force. As often happens in totalitarian regimes, where opposition is rarely tolerated, the Church is looked upon as the only group capable of restoring democratic rule. The Nigerian Church, in its opposition to the continuation of military rule, in its insistence on a secular state and in its call for a renewed political witness of its faithful, is providing a leadership that is in line with international human rights efforts. The Imperatives ofPolitical Witness What the Church needs is not adulators to extol the status quo, but men whose humility and obedience are no less than their passion for truth; men who brave every misunderstanding and attack as they bear witness. -

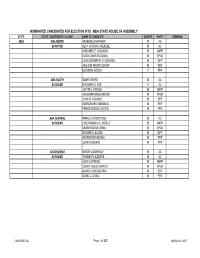

Nominated Candidates for Election Into Abia State

NOMINATED CANDIDATES FOR ELECTION INTO ABIA STATE HOUSE OF ASSEMBLY STATE STATE CONSTITUENCY & CODE NAME OF CANDIDATE GENDER PARTY REMARKS ABIA ABA NORTH AKOBUNDU NWANERI M AA SC/001/AB ALOY CHUKWU OKEREKE M AC OGBUMBA E. OGBUMBA M ANPP ELODI CHARLES AZUKA M APGA UGOCHINYERE N. E. UZUEGBU M DPP AKUJIOBI NKORO OSCAR M PDP BLESSING AZURU F PPA ABA SOUTH SMART EBERE M AA SC/002/AB EUCHARIA C. EZE F AC JUSTIN C. NWOGU M ANPP AHUKANNA MADUABUCHI M APGA JOHN M. OGUMIKE M DPP EMERUEUWA EMMANUEL M PDP PRINCE NWOGU OKORO M PPA ABA CENTRAL PRINCE CHIGBO IGWE M AC SC/003/AB CHIZARAMOKU A. OGBUJI M ANPP UBANI IRONUA UBANI M APGA GODWIN A. ELECHI M DPP OKORIE NWOKEOMA M PDP UZOR AZUBUIKE M PPA AROCHUKWU OKEZIE LAWRENCE M AA SC/004/AB THOMAS N. EZEIKPE M AC ALEX OJI EKUBO M ANPP UDENYI OKECHUKWU C. M APGA OKAFOR OKOREAFFIA M PDP AGWU U. UGWU M PPA CONFIDENTIAL Page 1 of 205 MARCH 14, 2007 BENDE NORTH OGWO UKACHI M. AA SC/005/AB DICKSON EJIAMA O. M. AC EKE ONYEMAUWA M. ANPP KALU ELIJAH AMAONWU M. APGA MICHAEL M. OFOR M. DPP UGWA SUNDAY M. PDP OJI LEKWAUWA M. PPA BENDE SOUTH IROEGBU FELIX M. AA SC/006/AB BARR. UCHE OGBONNAYA M. AC EGU N. EMMANUEL M. ANPP OLU-MORRIS I. NNENNA F APGA CHARLES CHUKWUDI M. DPP DIKE OKAY EMMANUEL M. PDP P. C. ONYEGBU M. PPA IKWUANO CHUKWU RAYMOND M AA SC/007AB UCHE F. MPAMAH M AC RICKSON UGOCHUKWU M ANPP CHUKWUEME OSOGBAKA M APGA DR. -

Historical Development of Vocational and Technical Education at the Secondary School Level in Kwara State from 1967 to 2012

HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT OF VOCATIONAL AND TECHNICAL EDUCATION AT THE SECONDARY SCHOOL LEVEL IN KWARA STATE FROM 1967 TO 2012 BY MOLAGUN, Heline Mosunmola 81/3162 A Thesis submitted to the Department of Arts Education, Faculty of Education, University of Ilorin, Ilorin, Nigeria In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Award of Doctor of Philosophy Degree (Ph.D) in History and Policy of Education June, 2015 COPYRIGHT PAGE HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT OF VOCATIONAL AND TECHNICAL EDUCATION AT THE SECONDARY SCHOOL LEVEL IN KWARA STATE FROM 1967 TO 2012 BY MOLAGUN, Heline Mosunmola 81/3162 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ©2015 DEDICATION This work is first and foremost dedicated to God who has been my helper, my teacher, my refuge and my dwelling place. He is the one that has made it possible for me to complete this programme. By His infinite mercy, He spared my life and gave me the power, the grace and the strength to face and tackle all the challenges that came my way while the programme was on. May His wonderful name be praised and be glorified forever in Jesus name. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I give glory, honour and adoration to the Almighty God who assisted me and also made it possible for me to complete this programme. By His infinite mercy, I received the divine health, the materials, wisdom, understanding and all the resources needed for this study. May His excellent name be praised forever in Jesus name. I am also very grateful to my loving, caring an d dynamic Supervisor, Prof. (Mrs) A. A. Jekayinfa. Undoubtedly, she is a motivator. -

Digitalcommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln (

DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln (https://digitalcommons.unl.edu) LIBRARY PHILOSOPHY AND PRACTICE (E-JOURNAL) (HTTPS://DIGITALCOMMONS.UNL.EDU/LIBPHILPRAC) Title Information seeking behavior in academic assignments using smartphone among elementary school students (https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi? article=6956&context=libphilprac) Authors Rahma Sugihartati, Department of Information and Library Science, Airlangga University (https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/do/search/? q=author_lname%3A%22Sugihartati%22%20author_fname%3A%22Rahma%22&start=0&context=52045) Follow (http://network.bepress.com/api/follow/subscribe? user=ZDZlNjAzZTdjNTE0ZWI5Mw%3D%3D&institution=MmZmZmExNzVkZDc0MDU1Ng%3D%3D&format=html) Date of this Version 11-19-2019 Abstract This article discusses information seeking behavior developed by elementary school students in completing academic assignments, their reasons for using smartphone to find information related to academic assignments, and students' opinions about the role of school libraries. All data presented in this article are the results of a study on 500 elementary school students in four major cities in East Java Province, Indonesia, namely Surabaya, Malang, Madiun and Malang. This study found that there has been a change in information seeking behavior among elementary students who no longer rely solely on information from textbooks in the libraries. The students have become part of the YouTube Generation that uses more social media (YouTube) via smartphone. According to the elementary school students, YouTube is a social media platform that provides information that is easily understood, while Google offers unlimited information. Students' confidence in the library as a source of information began to fade. Students in the millennial era often perceived libraries as sources of information from school textbooks, not as sources of information that are able to provide broad and varied information. -

1 Independent National Electoral Commission 2019 State House of Assembly Elections Held on 9Th, 23Rd March and 13Th April 2019 L

INDEPENDENT NATIONAL ELECTORAL COMMISSION 2019 STATE HOUSE OF ASSEMBLY ELECTIONS HELD ON 9TH, 23RD MARCH AND 13TH APRIL 2019 LIST OF MEMBERS-ELECT OF STATE HOUSES OF ASSEMBLY STATE S/N CONSTITUENCY CODE CANDIDATE GENDER PARTY REMARKS ABIA 1 ABA NORTH SC/01/AB UZODIKE AARON M PDP 2 ABA SOUTH SC/02/AB OBINNA ICHITA MARTIN M APGA 24 3 ABA CENTRAL SC/03/AB ABRAHAM OBA UKEFI M APGA 4 AROCHUKWU SC/04/AB ONYEKWERE. M. UKOHA M APGA 5 BENDE NORTH SC/05/AB CHUKWU CHIJIOKE M APC 6 BENDE SOUTH SC/06/AB EMMANUEL C. NDUBUISI M PDP 7 IKWUANO SC/07/AB STANLEY NWABUISI M PDP 8 ISIALA NGWA NORTH SC/08/AB ONWUSIBE GINGER M PDP 9 ISIALA NGWA SOUTH SC/09/AB CHIKWENDU KALU M PDP 10 ISUIKWUATO SC/10/AB EMEKA OKOROAFOR M APC 11 OBINGWA EAST SC/11/AB SOLOMON AKPULONU U. M PDP 12 OBINGWA WEST SC/12/AB THOMAS NKORO A.C. M PDP 13 OHAFIA NORTH SC/13/AB EGWURONU OBASI M PDP 1 14 OHAFIA SOUTH SC/14/AB IFEANYI UCHENDU M PDP 15 OSISIOMA NORTH SC/15/AB KENNEDY NJOKU M PDP 16 OSISIOMA SOUTH SC/16/AB NNAMDI ALLEN M PDP 17 UMUNNEOCHI SC/17/AB OKEY IGWE M PDP 18 UGWUNAAGBO SC/18/AB MUNACHIM I. ALOZIE M PDP 19 UKWA EAST SC/19/AB PAUL TARIBO M PDP 20 UKWA WEST SC/20/AB GODWIN ADIELE M PDP 21 UMUAHIA EAST SC/21/AB CHUKWUDI APUGO M PDP 22 UMUAHIA NORTH SC/22/AB KELECHI ONUZURUIKE M PDP 23 UMUAHIA CENTRAL SC/23/AB CHINEDUM ORJI M PDP 24 UMUAHIA SOUTH SC/24/AB JEREMIAH OGONNAYA UZOSIKE M PDP ADAMAWA 25 YOLA SOUTH SC/25/AD KABIRU MIJINYAWA M APC 26 YOLA NORTH SC/26/AD SAJO HAMIDU A. -

West African College of Surgeons

WEST AFRICAN COLLEGE OF SURGEONS APRIL 2019 PRIMARY FELLOWSHIP CANDIDATES ELIGIBLE LIST S/N Faculty Part Title Other Name(s) Surname Country Sex Address Centre Exam No 1 Anaesthesia Primary Dr. Abdulhameed Abioye ABDULAZEEZ Nigeria Male FEDERAL AbujaMEDICAL CENTRE,191001 AP.M. B 14, BIDA NIGER STATE 2 Anaesthesia Primary Dr. Aliyu Musa ABDULLAHI Nigeria Male Dr. Aliyu AbdullahiAbuja musa,Chairman191002 A MAC's Office,Federal Teaching Hospital Gombe,Along Ashaka road,P.M.B. 0037,Gombe State. 3 Anaesthesia Primary Dr. Mumin ABDULMALIK Nigeria Male NO.1 LEGISLATIVEAbuja QUARTERS191003 A UNGWAN/DOSA, KADUNA NORTH, KADUNA. 4 Anaesthesia Primary Dr. Olamiji, Jamiu ABDULSALAM Nigeria Male 13,riverviewAbuja estate ikenne191004 Remo, AOgun state 5 Anaesthesia Primary Dr. Joshua Opeyemi ABIFARIN Nigeria Male S38, AkoduIbadan area, Apete,191005 Ibadan. A 6 Anaesthesia Primary Dr. Olayemi Qoyyum ADEMAKINWA Nigeria Male P O Box 1471Ibadan Osogbo Osun191006 State A 7 Anaesthesia Primary Dr. Ayobami Oluwatobi ADEWOLE Nigeria Female PLOT 491, AbujaCONSTITUTION191007 AVENUE,A CENTRAL BUSINESS AREA, ABUJA. 8 Anaesthesia Primary Dr. Adewale Oluwasegun ADEWUMI Nigeria Male P.O Box 19725,Ibadan U. I Post191008 Office, Ibadan,A Oyo State. 9 Anaesthesia Primary Dr. Sandra Lois ADU-BOAHEN Ghana Female Dept. of Anaesthesia,Kumasi KATH,191009 P.O.A Box KS 1934 10 Anaesthesia Primary Dr. Sylvanus Oga AGBENYI Nigeria Male Ohuhu Owo,Abuja Oju Local 191010GovernmentA Area, Benue State. 11 Anaesthesia Primary Dr. Jude Adikwu AGBO Nigeria Male DepartmentAbuja of Accident191011 and Emergency,A Benue State University Teaching Hospital, Makurdi. 12 Anaesthesia Primary Dr. Stephen Orowo AGBORO Nigeria Male House 5 AcloseAbuja off 3rd 191012avenue, EfabA City Estate Life Camp FCT Abuja 13 Anaesthesia Primary Dr. -

The Erin-Ile/Offa Conflicts in Perspective

www.ijird.com July, 2019 Vol 8 Issue 7 ISSN 2278 – 0211 (Online) Interrogating Governments’ Interventions in Communal Clashes: The Erin-Ile/Offa Conflicts in Perspective Ayodele Dele Akinnusi Doctoral Student, Department of Political Science and Public Administration, Babcock University, Ilishan-Remo, Ogun State, Nigeria Dr. Oladimeji David Alao Associate Professor, Department of Political Science and Public Administration, Babcock University, Ilishan-Remo, Ogun State, Nigeria Dr. Ayuba Gimba Mavalla Associate Professor, Department of Political Science and Public Administration, Babcock University, Ilishan-Remo, Ogun State, Nigeria Abstract: It is a fact that conflicts are inevitable occurrences in the relationships between individuals and groups. The management of conflicts however determines whether the conflicts will become destabilizing and destructive or will lead to enhanced peace, progress and better relations of the parties involved in the conflicts. The role of government in the management of conflicts is of paramount importance given the fact that the maintenance of peace and security and the promotion of the welfare of citizens remain the top priorities of governments all over the world. This study, which employed the descriptive research method, interrogated governments’ interventions in the Erin-Ile/Offa border disputes and it concluded that the interventions failed to resolve the conflicts as the interventions were always viewed by the gladiators as being favour able to either of the two parties to the conflicts. This study therefore recommended a workable political arrangement for the peaceful co- existence of the two communities. Keywords: Border disputes, Communal clashes, Government interventions 1. Historical Fact of Erin-Ile/Offa Conflict 1.1. Historical Facts of Offa Offa is an ancient town and Headquarter of Offa Local Government Area of Kwara State, Nigeria.