Programmes in Nigeria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Democratic Transition in Anglophone West Africa Byjibrin Ibrahim

Democratic Transition in Anglophone West Africa Democratic Transition in Anglophone West Africa Jibrin Ibrahim Monograph Series The CODESRIA Monograph Series is published to stimulate debate, comments, and further research on the subjects covered. The Series will serve as a forum for works based on the findings of original research, which however are too long for academic journals but not long enough to be published as books, and which deserve to be accessible to the research community in Africa and elsewhere. Such works may be case studies, theoretical debates or both, but they incorporate significant findings, analyses, and critical evaluations of the current literature on the subjects in question. Author Jibrin Ibrahim directs the International Human Rights Law Group in Nigeria, which he joined from Ahmadu Bello University where he was Associate Professor of Political Science. His research interests are democratisation and the politics of transition, comparative federalism, religious and ethnic identities, and the crisis in social provisioning in Africa. He has edited and co-edited a number of books, among which are Federalism and Decentralisation in Africa (University of Fribourg, 1999), Expanding Democratic Space in Nigeria (CODESRIA, 1997) and Democratisation Processes in Africa, (CODESRIA, 1995). Democratic Transition in Anglophone West Africa © Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa 2003, Avenue Cheikh Anta Diop Angle Canal IV, BP. 3304, Dakar, Senegal. Web Site: http://www.codesria.org CODESRIA gratefully -

Address by His Excellency, Gov. Rabiu Musa Kwankwaso Fnse Of

ADDRESS BY HIS EXCELLENCY, GOV. RABIU MUSA KWANKWASO FNSE OF KANO STATE ON THE OCCASION OF PRESENTATION OF THE YEAR 2014 BUDGET PROPOSAL TO KANO STATE HOUSE OF ASSEMBLY ON TUESDAY 24th DECEMBER 2013 COURTESIES: ASSALAMU ALAIKUM. All praises are due to Allah, The most Beneficent, and the most Merciful. May the peace and blessings of Allah (SWT) be upon our Noble Prophet Muhammad (SAW), His Noble family and righteous companions. 2. Mr. Speaker let me begin by once again registering my condolences to this Honourable House over the unfortunate death of Hon. Ibrahim Abba Garko and Hon. Danladi Isa Kademi who lost their lives while serving the good people of Kano state. Equally, let me also convey on behalf of the Government our deep heartfelt condolences to the families and people of Kano State over the death of some prominent citizens of the state like Shiekh Ali Harazumi, Alhaji Ali Talle Kachako, Shiekh Isa Waziri, Sarkin Sharifai, Sheik Abubakar Dangoggo, Shiek Mudi Salga, Justice Halliru Abdullahi, Justice Sadi Mato Umar Abdul-Azeez Fadar Bege, as well as other sons and daughters of the state who lost their lives during the outgoing year. May Allah SWT reward them with Jannatul-firdaus. 3. May I also use this opportunity to congratulate our son and brother Kabiru Abubakar Musa and other winners for doing the state and the country at large proud by emerging the overall winner of the International Quranic Recitation Competition in Saudi Arabia, we pray that Almighty Allah bless them abundantly. 4. It gives me great pleasure and honour to be amongst this august gathering for the purpose of accounting for our stewardship and once again presenting the 2014 Proposed Appropriation bill before this Honourable House. -

The Izala Movement in Nigeria Genesis, Fragmentation and Revival

n the basis on solid fieldwork in northern Nigeria including participant observation, 18 Göttingen Series in Ointerviews with Izala, Sufis, and religion experts, and collection of unpublished Social and Cultural Anthropology material related to Izala, three aspects of the development of Izala past and present are analysed: its split, its relationship to Sufis, and its perception of sharīʿa re-implementation. “Field Theory” of Pierre Bourdieu, “Religious Market Theory” of Rodney Start, and “Modes Ramzi Ben Amara of Religiosity Theory” of Harvey Whitehouse are theoretical tools of understanding the religious landscape of northern Nigeria and the dynamics of Islamic movements and groups. The Izala Movement in Nigeria Genesis, Fragmentation and Revival Since October 2015 Ramzi Ben Amara is assistant professor (maître-assistant) at the Faculté des Lettres et des Sciences Humaines, Sousse, Tunisia. Since 2014 he was coordinator of the DAAD-projects “Tunisia in Transition”, “The Maghreb in Transition”, and “Inception of an MA in African Studies”. Furthermore, he is teaching Anthropology and African Studies at the Centre of Anthropology of the same institution. His research interests include in Nigeria The Izala Movement Islam in Africa, Sufism, Reform movements, Religious Activism, and Islamic law. Ramzi Ben Amara Ben Amara Ramzi ISBN: 978-3-86395-460-4 Göttingen University Press Göttingen University Press ISSN: 2199-5346 Ramzi Ben Amara The Izala Movement in Nigeria This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Published in 2020 by Göttingen University Press as volume 18 in “Göttingen Series in Social and Cultural Anthropology” This series is a continuation of “Göttinger Beiträge zur Ethnologie”. -

PROVISIONAL LIST.Pdf

S/N NAME YEAR OF CALL BRANCH PHONE NO EMAIL 1 JONATHAN FELIX ABA 2 SYLVESTER C. IFEAKOR ABA 3 NSIKAK UTANG IJIOMA ABA 4 ORAKWE OBIANUJU IFEYINWA ABA 5 OGUNJI CHIDOZIE KINGSLEY ABA 6 UCHENNA V. OBODOCHUKWU ABA 7 KEVIN CHUKWUDI NWUFO, SAN ABA 8 NWOGU IFIONU TAGBO ABA 9 ANIAWONWA NJIDEKA LINDA ABA 10 UKOH NDUDIM ISAAC ABA 11 EKENE RICHIE IREMEKA ABA 12 HIPPOLITUS U. UDENSI ABA 13 ABIGAIL C. AGBAI ABA 14 UKPAI OKORIE UKAIRO ABA 15 ONYINYECHI GIFT OGBODO ABA 16 EZINMA UKPAI UKAIRO ABA 17 GRACE UZOME UKEJE ABA 18 AJUGA JOHN ONWUKWE ABA 19 ONUCHUKWU CHARLES NSOBUNDU ABA 20 IREM ENYINNAYA OKERE ABA 21 ONYEKACHI OKWUOSA MUKOSOLU ABA 22 CHINYERE C. UMEOJIAKA ABA 23 OBIORA AKINWUMI OBIANWU, SAN ABA 24 NWAUGO VICTOR CHIMA ABA 25 NWABUIKWU K. MGBEMENA ABA 26 KANU FRANCIS ONYEBUCHI ABA 27 MARK ISRAEL CHIJIOKE ABA 28 EMEKA E. AGWULONU ABA 29 TREASURE E. N. UDO ABA 30 JULIET N. UDECHUKWU ABA 31 AWA CHUKWU IKECHUKWU ABA 32 CHIMUANYA V. OKWANDU ABA 33 CHIBUEZE OWUALAH ABA 34 AMANZE LINUS ALOMA ABA 35 CHINONSO ONONUJU ABA 36 MABEL OGONNAYA EZE ABA 37 BOB CHIEDOZIE OGU ABA 38 DANDY CHIMAOBI NWOKONNA ABA 39 JOHN IFEANYICHUKWU KALU ABA 40 UGOCHUKWU UKIWE ABA 41 FELIX EGBULE AGBARIRI, SAN ABA 42 OMENIHU CHINWEUBA ABA 43 IGNATIUS O. NWOKO ABA 44 ICHIE MATTHEW EKEOMA ABA 45 ICHIE CORDELIA CHINWENDU ABA 46 NNAMDI G. NWABEKE ABA 47 NNAOCHIE ADAOBI ANANSO ABA 48 OGOJIAKU RUFUS UMUNNA ABA 49 EPHRAIM CHINEDU DURU ABA 50 UGONWANYI S. AHAIWE ABA 51 EMMANUEL E. -

The Struggle Over Secularism Andits Implications for Politics And

DiScUSSion paper 49 Endangered Democracy? t h e s t r u g g l e o v e r s e c u l a r i s m a n d i t s implications f o r politics a n d d e m o c r a c y in nigeria u s m a n t a r a n d a b b a g a n a s h e t t i m a ISSN 1104-8417 ISBN 978-91-7106-666-4 DISCUSSION PAPER 49 Endangered Democracy? The Struggle over Secularism and its Implications for Politics and Democracy in Nigeria USMAN TAR and ABBA GANA SHEttIMA NORDISKA AFRIKAINSTITUTET, UPPSALA 2010 Indexing terms Politics Religion Secularism State Political power Democracy Islam Christianity Pluralism Religious groups Political conflicts Nigeria The opinions expressed in this volume are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Nordiska Afrikainstitutet. Language checking: Peter Colenbrander ISSN 1104-8417 ISBN 978-91-7106-666-4 © the authors and Nordiska Afrikainstitutet 2010 Grafisk Form Elin Olsson Contents Foreword .....................................................................................................................................................................................4 Introduction ...............................................................................................................................................................................5 Religion, Secularism and Politics – Conceptual Issues ...............................................................................................6 Religion, Secularism and Politics in Postcolonial Nigeria .........................................................................................9 -

Con Vol 27. No 1. 2020.Cdr

Vol. 27. No. 1 Of Vol. 27 No.1 2020 Journal of Curriculum Organization of Nigeria (CON) ISSN: 0189-9465 i Vol. 27. No. 1 NIGERIAN JOURNAL OF CURRICULUM STUDIES EDITORIAL BOARD (ISSN 0189 - 9465) Editor Professor Uchenna Nzewi Faculty of Education University of Nigeria, Nsukka Associate Editors Faculty of Education University of Nigeria, Nsukka Professor G. C. Offorma Professor I. M. Kalu Faculty of Education University of Calabar, Calabar Professor Nnenna Kanno Faculty of Education, Michael Okpara Univ., Umudike. Professor Abeke Adesanya Faculty of Education Olabisi Onabanjo University Ago-Iwoye, Ogun State Professor Akon E. O. Esu Faculty of Education University of Calabar, Calabar Professor A. E. Udosen Faculty of Education University of Uyo, Uyo Editorial Advisers: Professor P. A. I. Obanya 10 Ladoke Akintola Avenue New Bodija, Ibadan, P. O. Box 7112, Secretariat, Agodi, Ibadan Professor Peter Lassa Faculty of Education University of Jos Professor U. M. O. Ivowi Foremost Educational Services Limited Lagos Professor R. D. Olarinoye College of Science and Engineering, Landmark University, Omu-Aran, Kwara, State All articles for publication should be sent to: Professor Uchenna M. Nzewi Department of Science Education, Faculty of Education, University of Nigeria, Nsukka. www. con.org.ng ii Vol. 27. No. 1 This Journal is a forum for the dissemination of research findings and reports on curriculum development, implementation, innovation, diversification and renewal. In developing a curriculum, it is often necessary to use the experiences of the past and present demands as well as practices within and outside the system to design a desirable educational programme. Problems and issues in comparative education are relevant in shaping the curriculum. -

Nigeria in Political Transition

Order Code IB98046 Issue Brief for Congress Received through the CRS Web Nigeria in Political Transition Updated June 26, 2002 Theodros Dagne Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress CONTENTS SUMMARY MOST RECENT DEVELOPMENTS BACKGROUND AND ANALYSIS Current Issues Historical and Political Background Transition to Civilian Rule Elections Current Economic and Social Conditions Issues in U.S.-Nigerian Relations Background The United States and the Obasanjo Government CONGRESSIONAL HEARINGS, REPORTS, AND DOCUMENTS FOR ADDITIONAL READING CRS Reports IB98046 06-26-02 Nigeria in Political Transition SUMMARY On June 8, 1998, General Sani Abacha, in U.S. assistance to Nigeria. In August 2000, the military leader who took power in Nigeria President Clinton paid a state visit to Nigeria. in 1993, died of a reported heart attack and He met with President Obasanjo in Abuja and was replaced by General Abdulsalam addressed the Nigerian parliament. Several Abubakar. On July 7, 1998, Moshood Abiola, new U.S. initiatives were announced, includ- the believed winner of the 1993 presidential ing increased support for AIDS prevention election, also died of a heart attack during a and treatment programs in Nigeria and en- meeting with U.S. officials. General Abubakar hanced trade and commercial development. released political prisoners and initiated politi- cal, economic, and social reforms. He also In May 2001, President Obasanjo met established a new independent electoral com- with President Bush and other senior officials mission and outlined a schedule for elections in Washington. The two presidents discussed and transition to civilian rule, pledging to a wide range of issues, including trade, peace- hand over power to an elected civilian govern- keeping, and the HIV/AIDS crisis in Africa. -

The Nigerian 2007 Election: a Guide for Journalists and Commentators

Africa Programme Briefing Note AFP BN 07/01 The Nigerian 2007 Election: A Guide for Journalists and Commentators Sola Tayo February 2007 Key Points: • Nigerians will vote in April for a president to replace Olusegun Obasanjo. The election is shaping up to be highly controversial. • Corruption remains a major concern, with allegations reaching as high as the Vice-Presidency. • Whoever wins will face the mounting challenges of the oil-rich but poor and increasingly violent Niger Delta region. Introduction Nigeria’s President, Olusegun Obasanjo, is bucking the trend set by some of his peers across the continent – he is stepping aside after two terms. As the leader of one of Africa’s largest economies, a leading producer and exporter of oil, he must have been greatly tempted to serve another term or two. In fact, he sought to alter the constitution to allow the reigning president to stay beyond two terms but the bid was thrown out by Senate. So who is likely to win favour with Nigeria’s 140 million-strong population? Before their bitter and public falling out last year, Obasanjo’s Vice-President Atiku Abubakar was viewed as his natural successor. Now, with the pair barely on speaking terms and accusing each other of corruption, Abubakar has been forced to campaign under the ticket of another party. Other candidates include the former military heavyweights Ibrahim Badamasi Babangida – the mention of whose name strikes fear into the hearts of many Nigerians – and Muhamadu Buhari. By complete contrast, Obasanjo’s chosen successor is the reclusive and softly spoken Umaru Musa Yar'Adua, the Governor of Katsina state. -

The Making of Sani Abacha There

To the memory of Bashorun M.K.O Abiola (August 24, 1937 to July 7, 1998); and the numerous other Nigerians who died in the hands of the military authorities during the struggle to enthrone democracy in Nigeria. ‘The cause endures, the HOPE still lives, the dream shall never die…’ onderful: It is amazing how Nigerians hardly learn frWom history, how the history of our politics is that of oppor - tunism, and violations of the people’s sovereignty. After the exit of British colonialism, a new set of local imperi - alists in military uniform and civilian garb assumed power and have consistently proven to be worse than those they suc - ceeded. These new vetoists are not driven by any love of coun - try, but rather by the love of self, and the preservation of the narrow interests of the power-class that they represent. They do not see leadership as an opportunity to serve, but as an av - enue to loot the public treasury; they do not see politics as a platform for development, but as something to be captured by any means possible. One after the other, these hunters of fortune in public life have ended up as victims of their own ambitions; they are either eliminated by other forces also seeking power, or they run into a dead-end. In the face of this leadership deficit, it is the people of Nigeria that have suffered; it is society itself that pays the price for the imposition of deranged values on the public space; much ten - sion is created, the country is polarized, growth is truncated. -

A Romance with Vultures1

A Romance with Vultures1 C. Krydz Ikwuemesi The years 1993 to 1998 were a particularly dark period for Nigeria. They were the gory years of the Abacha dictatorship, with all its characteristic harshness and wanton brutality. They were the years of the triumph of evil, even falsehood and intolerance were shame- lessly woven into the creed of leadership, when it was anathema to stand up for one’s rights. The ASUU (Academic Staff Union of Universities) strike of 1996 was one of the many moments in his- tory when the above scenario was most vividly dramatised. Apparently buoyed by the successes of a 1992/93 strike which brought some measure of improvement to the university system, the ASUU embarked on a fresh strike in 1996 to press for further improvement. The government had reneged on some aspects of the 1992 agreement; the groveling inflation in the country had eroded any relief accruing from the 1992 agreement; students and faculty coped with poor study and work conditions; Nige- rian universities had become a ghost of themselves; and above all, the Nigerian professor earned in a year what an average menial worker in the U.S.A. or South Africa, for instance, would earn in a couple of weeks. It was thus overdue that a change be demanded and negotiated. Change and Negotiation. Those were the watchwords of the ASUU during the 1996 strike. The negotiations took place between the government and ASUU officials, but the much- desired change was not to be. In its characteristic nihilist manner, the Abacha administration frustrated the negotiations mid-way and banned the ASUU as a way of halting the strike. -

143-154 ISSN 1994-9057 (Print) ISSN 2070-0083 (Online) DOI

AFRREV VOL 14 (1), S/NO 57, JANUARY, 2020 African Research Review: An International Multidisciplinary Journal, Ethiopia AFRREV Vol. 14 (1), Serial No 57, January, 2020: 143-154 ISSN 1994-9057 (Print) ISSN 2070-0083 (Online) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/afrrev.v14i1.13 A Tortuous Trajectory: Nigerian Foreign Policy under Military Rule, 1985 – 1999 Osayande, Emmanuel Department of History and Strategic Studies Faculty of Arts University of Lagos Akoka, Yaba, Lagos, Nigeria Abstract This article critically examined the complexities that abound in Nigeria’s Foreign Policy under the final three military administrations of Generals Ibrahim Babangida, Sani Abacha, and Abdulsalami Abubakar, before the transition to democratic rule in 1999. It adopted a novel approach by identifying and intricately examining a distinct pattern of contortion evinced in Nigeria’s foreign policy during this epoch. It contended that although Nigeria’s foreign policy had historically been somewhat knotty at varying points in time, this period in its foreign policy and external relations was especially marked by tortuousness and a somewhat back and forth agenda. This began in 1985 with the Babangida administration, whose foreign policy posture initially seemed commendable, only for political debacles to mar it. An exacerbation of this downslide in foreign policy occurred under the Abacha regime, whereby the country obtained pariah status among the comity of nations. Subsequently, a revitalisation occurred under General Abubakar, who deviated from what had become the status quo, reinventing Nigeria’s external image and foreign policy position through his ‘restoration campaign.’ More so, following David Gray’s behavioural theory of foreign policy, this study examined how the behavioural patterns and aspirations of a minuscule cadre of decision-makers deeply affected Nigeria’s foreign policy formulation and implementation during the period under study. -

Resricted 1 Restricted Schedule of Activities For

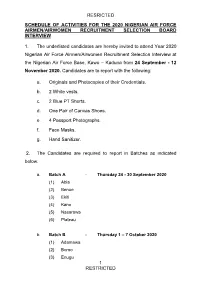

RESRICTED SCHEDULE OF ACTIVITIES FOR THE 2020 NIGERIAN AIR FORCE AIRMEN/AIRWOMEN RECRUITMENT SELECTION BOARD INTERVIEW 1. The underlisted candidates are hereby invited to attend Year 2020 Nigerian Air Force Airmen/Airwomen Recruitment Selection Interview at the Nigerian Air Force Base, Kawo – Kaduna from 24 September - 12 November 2020. Candidates are to report with the following: a. Originals and Photocopies of their Credentials. b. 2 White vests. c. 2 Blue PT Shorts. d. One Pair of Canvas Shoes. e. 4 Passport Photographs. f. Face Masks. g. Hand Sanitizer. 2. The Candidates are required to report in Batches as indicated below: a. Batch A - Thursday 24 - 30 September 2020 (1) Abia (2) Benue (3) Ekiti (4) Kano (5) Nasarawa (6) Plateau b. Batch B - Thursday 1 – 7 October 2020 (1) Adamawa (2) Borno (3) Enugu 1 RESTRICTED RESRICTED (4) Katsina (5) Niger (6) Rivers c. Batch C - Thursday 8 – 14 October 2020 (1) Akwa Ibom (2) Cross River (3) Gombe (4) Kebbi (5) Ogun (6) Sokoto d. Batch D - Thursday 15 – 21 October 2020 (1) Anambra (2) Delta (3) Imo (4) Kogi (5) Ondo (6) Taraba e. Batch E - Thursday 22 – 28 October 2020 (1) Bauchi (2) Ebonyi (3) Jigawa (4) Kwara (5) Osun (6) Yobe f. Batch F - Thursday 29 October – 5 November 2020 (1) Bayelsa (2) Edo (3) Kaduna 2 RESTRICTED RESRICTED (4) Lagos (5) Oyo (6) Zamfara (7) FCT Note: Face masks are to be worn and other COVID-19 preventive measures are to be strictly observed throughout the exercise. SIGNED MAHMOUD EL-HAJI AHMED Air Vice Marshal for Chief of the Air Staff 3 RESTRICTED RESTRICTED SHORTLISTED