A Romance with Vultures1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Address by His Excellency, Gov. Rabiu Musa Kwankwaso Fnse Of

ADDRESS BY HIS EXCELLENCY, GOV. RABIU MUSA KWANKWASO FNSE OF KANO STATE ON THE OCCASION OF PRESENTATION OF THE YEAR 2014 BUDGET PROPOSAL TO KANO STATE HOUSE OF ASSEMBLY ON TUESDAY 24th DECEMBER 2013 COURTESIES: ASSALAMU ALAIKUM. All praises are due to Allah, The most Beneficent, and the most Merciful. May the peace and blessings of Allah (SWT) be upon our Noble Prophet Muhammad (SAW), His Noble family and righteous companions. 2. Mr. Speaker let me begin by once again registering my condolences to this Honourable House over the unfortunate death of Hon. Ibrahim Abba Garko and Hon. Danladi Isa Kademi who lost their lives while serving the good people of Kano state. Equally, let me also convey on behalf of the Government our deep heartfelt condolences to the families and people of Kano State over the death of some prominent citizens of the state like Shiekh Ali Harazumi, Alhaji Ali Talle Kachako, Shiekh Isa Waziri, Sarkin Sharifai, Sheik Abubakar Dangoggo, Shiek Mudi Salga, Justice Halliru Abdullahi, Justice Sadi Mato Umar Abdul-Azeez Fadar Bege, as well as other sons and daughters of the state who lost their lives during the outgoing year. May Allah SWT reward them with Jannatul-firdaus. 3. May I also use this opportunity to congratulate our son and brother Kabiru Abubakar Musa and other winners for doing the state and the country at large proud by emerging the overall winner of the International Quranic Recitation Competition in Saudi Arabia, we pray that Almighty Allah bless them abundantly. 4. It gives me great pleasure and honour to be amongst this august gathering for the purpose of accounting for our stewardship and once again presenting the 2014 Proposed Appropriation bill before this Honourable House. -

The Izala Movement in Nigeria Genesis, Fragmentation and Revival

n the basis on solid fieldwork in northern Nigeria including participant observation, 18 Göttingen Series in Ointerviews with Izala, Sufis, and religion experts, and collection of unpublished Social and Cultural Anthropology material related to Izala, three aspects of the development of Izala past and present are analysed: its split, its relationship to Sufis, and its perception of sharīʿa re-implementation. “Field Theory” of Pierre Bourdieu, “Religious Market Theory” of Rodney Start, and “Modes Ramzi Ben Amara of Religiosity Theory” of Harvey Whitehouse are theoretical tools of understanding the religious landscape of northern Nigeria and the dynamics of Islamic movements and groups. The Izala Movement in Nigeria Genesis, Fragmentation and Revival Since October 2015 Ramzi Ben Amara is assistant professor (maître-assistant) at the Faculté des Lettres et des Sciences Humaines, Sousse, Tunisia. Since 2014 he was coordinator of the DAAD-projects “Tunisia in Transition”, “The Maghreb in Transition”, and “Inception of an MA in African Studies”. Furthermore, he is teaching Anthropology and African Studies at the Centre of Anthropology of the same institution. His research interests include in Nigeria The Izala Movement Islam in Africa, Sufism, Reform movements, Religious Activism, and Islamic law. Ramzi Ben Amara Ben Amara Ramzi ISBN: 978-3-86395-460-4 Göttingen University Press Göttingen University Press ISSN: 2199-5346 Ramzi Ben Amara The Izala Movement in Nigeria This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Published in 2020 by Göttingen University Press as volume 18 in “Göttingen Series in Social and Cultural Anthropology” This series is a continuation of “Göttinger Beiträge zur Ethnologie”. -

Nigeria in Political Transition

Order Code IB98046 Issue Brief for Congress Received through the CRS Web Nigeria in Political Transition Updated June 26, 2002 Theodros Dagne Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress CONTENTS SUMMARY MOST RECENT DEVELOPMENTS BACKGROUND AND ANALYSIS Current Issues Historical and Political Background Transition to Civilian Rule Elections Current Economic and Social Conditions Issues in U.S.-Nigerian Relations Background The United States and the Obasanjo Government CONGRESSIONAL HEARINGS, REPORTS, AND DOCUMENTS FOR ADDITIONAL READING CRS Reports IB98046 06-26-02 Nigeria in Political Transition SUMMARY On June 8, 1998, General Sani Abacha, in U.S. assistance to Nigeria. In August 2000, the military leader who took power in Nigeria President Clinton paid a state visit to Nigeria. in 1993, died of a reported heart attack and He met with President Obasanjo in Abuja and was replaced by General Abdulsalam addressed the Nigerian parliament. Several Abubakar. On July 7, 1998, Moshood Abiola, new U.S. initiatives were announced, includ- the believed winner of the 1993 presidential ing increased support for AIDS prevention election, also died of a heart attack during a and treatment programs in Nigeria and en- meeting with U.S. officials. General Abubakar hanced trade and commercial development. released political prisoners and initiated politi- cal, economic, and social reforms. He also In May 2001, President Obasanjo met established a new independent electoral com- with President Bush and other senior officials mission and outlined a schedule for elections in Washington. The two presidents discussed and transition to civilian rule, pledging to a wide range of issues, including trade, peace- hand over power to an elected civilian govern- keeping, and the HIV/AIDS crisis in Africa. -

The Nigerian 2007 Election: a Guide for Journalists and Commentators

Africa Programme Briefing Note AFP BN 07/01 The Nigerian 2007 Election: A Guide for Journalists and Commentators Sola Tayo February 2007 Key Points: • Nigerians will vote in April for a president to replace Olusegun Obasanjo. The election is shaping up to be highly controversial. • Corruption remains a major concern, with allegations reaching as high as the Vice-Presidency. • Whoever wins will face the mounting challenges of the oil-rich but poor and increasingly violent Niger Delta region. Introduction Nigeria’s President, Olusegun Obasanjo, is bucking the trend set by some of his peers across the continent – he is stepping aside after two terms. As the leader of one of Africa’s largest economies, a leading producer and exporter of oil, he must have been greatly tempted to serve another term or two. In fact, he sought to alter the constitution to allow the reigning president to stay beyond two terms but the bid was thrown out by Senate. So who is likely to win favour with Nigeria’s 140 million-strong population? Before their bitter and public falling out last year, Obasanjo’s Vice-President Atiku Abubakar was viewed as his natural successor. Now, with the pair barely on speaking terms and accusing each other of corruption, Abubakar has been forced to campaign under the ticket of another party. Other candidates include the former military heavyweights Ibrahim Badamasi Babangida – the mention of whose name strikes fear into the hearts of many Nigerians – and Muhamadu Buhari. By complete contrast, Obasanjo’s chosen successor is the reclusive and softly spoken Umaru Musa Yar'Adua, the Governor of Katsina state. -

The Making of Sani Abacha There

To the memory of Bashorun M.K.O Abiola (August 24, 1937 to July 7, 1998); and the numerous other Nigerians who died in the hands of the military authorities during the struggle to enthrone democracy in Nigeria. ‘The cause endures, the HOPE still lives, the dream shall never die…’ onderful: It is amazing how Nigerians hardly learn frWom history, how the history of our politics is that of oppor - tunism, and violations of the people’s sovereignty. After the exit of British colonialism, a new set of local imperi - alists in military uniform and civilian garb assumed power and have consistently proven to be worse than those they suc - ceeded. These new vetoists are not driven by any love of coun - try, but rather by the love of self, and the preservation of the narrow interests of the power-class that they represent. They do not see leadership as an opportunity to serve, but as an av - enue to loot the public treasury; they do not see politics as a platform for development, but as something to be captured by any means possible. One after the other, these hunters of fortune in public life have ended up as victims of their own ambitions; they are either eliminated by other forces also seeking power, or they run into a dead-end. In the face of this leadership deficit, it is the people of Nigeria that have suffered; it is society itself that pays the price for the imposition of deranged values on the public space; much ten - sion is created, the country is polarized, growth is truncated. -

143-154 ISSN 1994-9057 (Print) ISSN 2070-0083 (Online) DOI

AFRREV VOL 14 (1), S/NO 57, JANUARY, 2020 African Research Review: An International Multidisciplinary Journal, Ethiopia AFRREV Vol. 14 (1), Serial No 57, January, 2020: 143-154 ISSN 1994-9057 (Print) ISSN 2070-0083 (Online) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/afrrev.v14i1.13 A Tortuous Trajectory: Nigerian Foreign Policy under Military Rule, 1985 – 1999 Osayande, Emmanuel Department of History and Strategic Studies Faculty of Arts University of Lagos Akoka, Yaba, Lagos, Nigeria Abstract This article critically examined the complexities that abound in Nigeria’s Foreign Policy under the final three military administrations of Generals Ibrahim Babangida, Sani Abacha, and Abdulsalami Abubakar, before the transition to democratic rule in 1999. It adopted a novel approach by identifying and intricately examining a distinct pattern of contortion evinced in Nigeria’s foreign policy during this epoch. It contended that although Nigeria’s foreign policy had historically been somewhat knotty at varying points in time, this period in its foreign policy and external relations was especially marked by tortuousness and a somewhat back and forth agenda. This began in 1985 with the Babangida administration, whose foreign policy posture initially seemed commendable, only for political debacles to mar it. An exacerbation of this downslide in foreign policy occurred under the Abacha regime, whereby the country obtained pariah status among the comity of nations. Subsequently, a revitalisation occurred under General Abubakar, who deviated from what had become the status quo, reinventing Nigeria’s external image and foreign policy position through his ‘restoration campaign.’ More so, following David Gray’s behavioural theory of foreign policy, this study examined how the behavioural patterns and aspirations of a minuscule cadre of decision-makers deeply affected Nigeria’s foreign policy formulation and implementation during the period under study. -

AC Vol 40 No 10

11 June 1999 Vol 40 No 12 AFRICA CONFIDENTIAL NIGERIA II 3 NIGERIA New team, old players All hail to the chief Like most Nigerian governments, President Olusegun Obasanjo returns to power amid hopes that the President Obasanjo's new team is country's decline can be reversed after 15 years of military rule an awkward coalition. He has Government business took off at a frenetic pace after the 29 May inauguration of President Olusegun nominated a mixture of Obasanjo. Launching proceedings, Obasanjo made a powerful attack on corrupt contractors, technocrats, political jobbers, soldiers and politicians to an audience that included international political celebrities (see Box). human rights activists and opposition politicians in a bid to Within hours of being sworn in as President, Obasanjo had cleared out many of the hold-overs from make a national administration. the outgoing military regime by retiring all the military service chiefs along with the Central Bank Governor and the Police Commissioner. Days later, he had set up two panels of eminent people to probe all contracts awarded this year by the outgoing military regime and human rights abuses during ZIMBABWE 4 General Sani Abacha’s rule, handed over a list of ministerial nominees to the Senate and started Where's the door? going through the country’s financial ledger with his economic advisors. The style of Obasanjo’s return to power has impressed all but the most sceptical, whether President Mugabe may not, after Nigerians or outsiders. By attacking the corruption of his predecessor governments in front of all, be heading for a speedy foreign guests and by promising to introduce comprehensive anti-graft legislation within a fortnight, retirement although he was 75 in February and has held power since Obasanjo showed surprising muscle. -

Utafiti Sera Research Brief Series,March 2021

Utafiti Sera Research Brief Series Issue 1, March 2021 Fuel subsidy in Nigeria: Lessons in leading the people’s side of the tussle In a nutshell widespread and led to significant policy initiatives (especially SURE-P). Since 2015 fuel prices have continuously gone up Each time the Federal Government of Nigeria considers the (once, down) but labour and the activists have not succeeded burden of fuel subsidy too heavy, it attempts to shed a bit of it. in getting people out onto the streets. In effect, they seem to Two things often follow: first, the prices of petroleum products have lost the ability and legitimacy to lead the people’s side and the cost of living instantly go up; second, the organised of the tussle. This has negative implications for the subsidy- labour and civil society organisations mobilise the citizens related contentions that sometimes bring reprieve for citizens, for protest. They assume the leading position among citizens even temporarily. In the study reported here, we examined articulating citizens’ side of the tussle in the narratives. In most how labour and others lost that role, and we draw out lessons cases, these protests take place and lead to a downward on how to lead the people’s side of a volatile tussle such as review of the prices of petroleum products; in a few cases the fuel subsidy issue. the protests barely take place. In 2012, the protests were Attempts to remove or reduce subsidy by different administrations in Nigeria Year President/Head of State Change in price Remarks 1973 Yakubu Gowon 6k to 8.45k -

Programmes in Nigeria

Nicholas Ibeawuchi Omenka - BETH 10: 21 The Winds of Change: The Church and the Transition to Civil Rule Programmes in Nigeria By Nicholas Ibeawuchi Omenka Abstract For more than a decade, military disengagement from African politics has been at the centre stage ofpolitical debate on the continent. While several African countries have recorded significant successes in this regard, the Nigerian experience has been one of a long succession of disappointments. This paper examines the various transition to civil rule programmes in Nigeria from. the perspective of the Church's reaction to them. It primarily establishes a synthesis of the various communiques and pronouncements of the Church leaders on the transition programmes and situates this within the Church's social teachings and the global insistence on human rights and free choice of governance. A central observation from this study is the fact that the transition programmes have transformed the otherwise politically passive Church leaders to a vocal and active political force. As often happens in totalitarian regimes, where opposition is rarely tolerated, the Church is looked upon as the only group capable of restoring democratic rule. The Nigerian Church, in its opposition to the continuation of military rule, in its insistence on a secular state and in its call for a renewed political witness of its faithful, is providing a leadership that is in line with international human rights efforts. The Imperatives ofPolitical Witness What the Church needs is not adulators to extol the status quo, but men whose humility and obedience are no less than their passion for truth; men who brave every misunderstanding and attack as they bear witness. -

Abacha C Newswatch OVERSEAS SUBSCRIPTION)

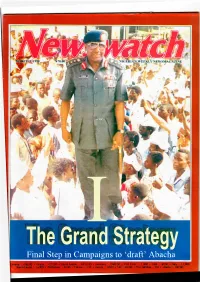

* '€■ 'sa*. %. i-M’ I The Grand Strategy Final Step in Campaigns to ‘draft’ Abacha C Newswatch OVERSEAS SUBSCRIPTION) This is to inform our numerous overseas readers and subscribers that we have resumed our Internationa} subscriber service. INTERNATIONAL SUBSCRIPTION RATES Newswatch ■U.KPBICES WWW 2 o co O) in Overseas Special Offer! 1 year (52 issues) Students 6 months 4(26 issues) Students cm One Month Free 3 months (13 issues) Students Subscription For The First 200 New Subscribers EUROPE/EIRE PRICES ^ -vi 1 Year (52 issues) £100 - Students cd BEAT THE RUSH !! 6 Months (26 issues) £55 - Students I s> to to to to to to 3 Months (13 issues) £30 - Students ro 4^ en o O USA/CANADA/ SOUTH AMERICA PRICES <N o o o 1 Year (52 issues) Students O T- 'si 6 Months (26 issues) Students cn AUSTRALIA/ FAR EAST PRICES 1 Year (52 issues) o students o> cn o to to cn 6 Months (26 issues) to to O 4^ students NORTH AFRICA/ MIPPLE EAST,PRICES 8 04 1 Year (52 issues) LO cn students o O to to 6 Months (26 issues) <j> students AFRICA (OTHER THAN ABOVE) 1 Year (52 issues) £130 students cd to to cn 6 Months (26 issues) £65 students cn Name:. Address:.................... .............. ................................... ...................................... ............................................ Tick l I Installments! Payment or I............... I Full Payment Enclosed here is a bank draft/cheque for.................................. ............................ ......................................... Signature:........ ...................................... .......................... ............................................................................. : NOTE: All students subscription must be accompanied by CURRENT EVIDENCE OF SCHOOL REGISTRATION. Cheques, Sterling Postal Order/Steriing Money Order should be made payable to NIGERIAN MAGAZINES LIMITED Existing and new Subscribers and Advertisers should contact:- Nigerian Magazines Limited. -

Nigeria Country Assessment

NIGERIA COUNTRY ASSESSMENT COUNTRY INFORMATION AND POLICY UNIT, ASYLUM AND APPEALS POLICY DIRECTORATE IMMIGRATION AND NATIONALITY DIRECTORATE VERSION APRIL 2000 I. SCOPE OF DOCUMENT 1.1 This assessment has been produced by the Country Information and Policy Unit, Immigration and Nationality Directorate, Home Office, from information obtained from a variety of sources. 1.2 The assessment has been prepared for background purposes for those involved in the asylum determination process. The information it contains is not exhaustive, nor is it intended to catalogue all human rights violations. It concentrates on the issues most commonly raised in asylum claims made in the United Kingdom. 1.3 The assessment is sourced throughout. It is intended to be used by caseworkers as a signpost to the source material, which has been made available to them. The vast majority of the source material is readily available in the public domain. 1.4 It is intended to revise the assessment on a 6-monthly basis while the country remains within the top 35 asylum producing countries in the United Kingdom. 1.5 The assessment has been placed on the Internet (http:www.homeoffice.gov.uk/ind/cipu1.htm). An electronic copy of the assessment has been made available to: Amnesty International UK Immigration Advisory Service Immigration Appellate Authority Immigration Law Practitioners' Association Joint Council for the Welfare of Immigrants JUSTICE 1 Medical Foundation for the Care of Victims of Torture Refugee Council Refugee Legal Centre UN High Commissioner for Refugees CONTENTS I. SCOPE OF DOCUMENT 1.1 - 1.5 II. GEOGRAPHY 2.1 III. ECONOMY 3.1 - 3.3 IV. -

Who Speaks for the North? Politics and Influence in Northern Nigeria

Research Paper Leena Koni Hoffmann Africa Programme | July 2014 Who Speaks for the North? Politics and Influence in Northern Nigeria Chatham House Who Speaks for the North? Politics and Influence in Northern Nigeria Summary points • Northern Nigeria is witnessing an upheaval in its political and social space. In 1999, important shifts in presidential politics led to the rebalancing of power relations between the north of Nigeria and the more economically productive south. This move triggered the unprecedented recalibration of influence held by northern leaders over the federal government. Goodluck Jonathan’s elevation to the presidency in 2010 upended the deal made by the political brokers of the People’s Democratic Party (PDP) to rotate power between the north and south, from which the party had derived much of its unity. • The decisive role played by the power shift issue in 15 years of democracy raises important questions about the long-term effectiveness of the elite pacts and regional rotation arrangements that have been used to manage the balance of power between the north and the south. It also highlights the fragility and uncertainties of Nigeria’s democratic transition, as well as the unresolved fault lines in national unity as the country commemorates the centenary of the unification of the north and south in 2014. • The significance and complexity of challenges in northern Nigeria make determining priorities for the region extremely difficult. Yet overcoming the north’s considerable problems relating to development and security are crucial to the realization of a shared and prosperous future for all of Nigeria. Strong economic growth in the past decade has provided the government with the opportunities and resources to pursue thoughtful strategies that can address the development deficit between the north and the more prosperous south as well as creating greater political inclusion.