Smithsonian Libraries Baird Society Resident Scholar Program Project 2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reversal of Precedence for Scarabaeus Monoceros Nicolson

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Center for Systematic Entomology, Gainesville, Insecta Mundi Florida 2014 Reversal of precedence for Scarabaeus monoceros Nicolson, 1776, in favor of Scarabaeus oblongus Palisot de Beauvois, 1807 to stabilize the nomenclature of Strategus oblongus (Palisot de Beauvois) from Hispaniola (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae: Dynastinae) Brett .C Ratcliffe University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/insectamundi Ratcliffe, Brett .,C "Reversal of precedence for Scarabaeus monoceros Nicolson, 1776, in favor of Scarabaeus oblongus Palisot de Beauvois, 1807 to stabilize the nomenclature of Strategus oblongus (Palisot de Beauvois) from Hispaniola (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae: Dynastinae)" (2014). Insecta Mundi. 871. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/insectamundi/871 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for Systematic Entomology, Gainesville, Florida at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Insecta Mundi by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. INSECTA MUNDI A Journal of World Insect Systematics 0370 Reversal of precedence for Scarabaeus monoceros Nicolson, 1776, in favor of Scarabaeus oblongus Palisot de Beauvois, 1807 to stabilize the nomenclature of Strategus oblongus (Palisot de Beauvois) from Hispaniola (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae: Dynastinae) Brett C. Ratcliffe Systematics Research Collections -

Lecythidaceae (G.T

Flora Malesiana, Series I, Volume 21 (2013) 1–118 LECYTHIDACEAE (G.T. Prance, Kew & E.K. Kartawinata, Bogor)1 Lecythidaceae A.Rich. in Bory, Dict. Class. Hist. Nat. 9 (1825) 259 (‘Lécythidées’), nom. cons.; Poit., Mém. Mus. Hist. Nat. Paris 13 (1835) 141; Miers, Trans. Linn. Soc. London, Bot. 30, 2 (1874) 157; Nied. in Engl. & Prantl, Nat. Pflanzenfam. 3, 7 (1892) 30; R.Knuth in Engl., Pflanzenr. IV.219, Heft 105 (1939) 26; Whitmore, Tree Fl. Malaya 2 (1973) 257; R.J.F.Hend., Fl. Australia 8 (1982) 1; Corner, Wayside Trees Malaya ed. 3, 1 (1988) 349; S.A.Mori & Prance, Fl. Neotrop. Monogr. 21, 2 (1990) 1; Chantar., Kew Bull. 50 (1995) 677; Pinard, Tree Fl. Sabah & Sarawak 4 (2002) 101; H.N.Qin & Prance, Fl. China 13 (2007) 293; Prance in Kiew et al., Fl. Penins. Malaysia, Ser. 2, 3 (2012) 175. — Myrtaceae tribus Lecythideae (A.Rich.) A.Rich. ex DC., Prodr. 3 (1828) 288. — Myrtaceae subtribus Eulecythideae Benth. & Hook.f., Gen. Pl. 1, 2 (1865) 695, nom. inval. — Type: Lecythis Loefl. Napoleaeonaceae A.Rich. in Bory, Dict. Class. Hist. Nat. 11 (1827) 432. — Lecythi- daceae subfam. Napoleonoideae Nied. in Engl. & Prantl., Nat. Pflanzenfam. 3, 7 (1893) 33. — Type: Napoleonaea P.Beauv. Scytopetalaceae Engl. in Engl. & Prantl, Nat. Pflanzenfam., Nachtr. 1 (1897) 242. — Lecythidaceae subfam. Scytopetaloideae (Engl.) O.Appel, Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 121 (1996) 225. — Type: Scytopetalum Pierre ex Engl. Lecythidaceae subfam. Foetidioideae Nied. in Engl. & Prantl, Nat Pflanzenfam. 3, 7 (1892) 29. — Foetidiaceae (Nied.) Airy Shaw in Willis & Airy Shaw, Dict. Fl. Pl., ed. -

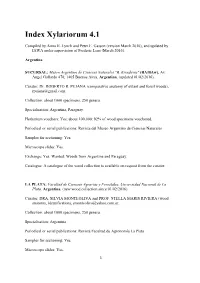

Index Xylariorum 4.1

Index Xylariorum 4.1 Compiled by Anna H. Lynch and Peter E. Gasson (version March 2010), and updated by IAWA under supervision of Frederic Lens (March 2016). Argentina SUCURSAL: Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales "B. Rivadavia" (BA/BAw), Av. Ángel Gallardo 470, 1405 Buenos Aires, Argentina. (updated 01/02/2016). Curator: Dr. ROBERTO R. PUJANA (comparative anatomy of extant and fossil woods), [email protected]. Collection: about 1000 specimens, 250 genera. Specialisation: Argentina, Paraguay. Herbarium vouchers: Yes; about 100,000; 92% of wood specimens vouchered. Periodical or serial publications: Revista del Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales Samples for sectioning: Yes. Microscope slides: Yes. Exchange: Yes. Wanted: Woods from Argentina and Paraguay. Catalogue: A catalogue of the wood collection is available on request from the curator. LA PLATA: Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias y Forestales, Universidad Nacional de La Plata. Argentina. (new wood collection since 01/02/2016). Curator: DRA. SILVIA MONTEOLIVA and PROF. STELLA MARIS RIVIERA (wood anatomy, identification), [email protected]. Collection: about 1000 specimens, 250 genera. Specialisation: Argentina Periodical or serial publications: Revista Facultad de Agronomía La Plata Samples for sectioning: Yes. Microscope slides: Yes. 1 Exchange: Yes. Wanted: woods from Argentina. Catalogue: A catalogue of the wood collection is available on request from the curator: www.maderasenargentina.com.ar TUCUMAN: Xiloteca of the Herbarium of the Fundation Miguel Lillo (LILw), Foundation Miguel Lillo - Institut Miguel Lillo, (LILw), Miguel Lillo 251, Tucuman, Argentina. (updated 05/08/2002). Foundation: 1910. Curator: MARIA EUGENIA GUANTAY, Lic. Ciencias Biologicas (anatomy of wood of Myrtaceae), [email protected]. Collection: 1,319 specimens, 224 genera. -

Evaluation of Antimicrobial Properties of Ethyl Acetate Extract of the Leaves of Napoleoneae Imperialis Family Lecythiaceae A.F

Int. J. Drug Res. Tech. 2011, Vol. 1 (1), 45-51 International Journal of Drug Research and Technology Available online at http://www.ijdrt.com/ Original Research Paper EVALUATION OF ANTIMICROBIAL PROPERTIES OF ETHYL ACETATE EXTRACT OF THE LEAVES OF NAPOLEONEAE IMPERIALIS FAMILY LECYTHIACEAE A.F. Onyegbule1*, C.F. Anowi2, T.H. Gugu3 and A.U. Uto-Nedosa4 1* Dept of Pharmaceutical and Medicinal Chemistry, Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka, Nigeria 2Dept of Pharmacognosy and Traditional Medicine, Faculty of Pharmaceutical sciences, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka, Nigeria 3 Dept of Pharmaceutical Microbiology and Biotechnology, Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka, Nigeria 4Dept of Pharmacology and Toxicology, Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka, Nigeria ABSTRACT Napoleonaea imperialis is used to treat wounds in Anambra State, Nigeria. Against this background, ethyl acetate extract of the leaves were screened against some microorganisms so as to ascertain this claim and to recommend it for further investigation for possible inclusion into official compendium. The plant leaves were dried, powdered subjected to cold maceration with ethyl acetate for 24 hours. Phytochemical screening was done for alkaloids, saponin, essential oil, phenolic group, steroidal nucleus, simple sugar, starch, cyanogenic glycoside, proteins and flavonoid using standard procedures. Antimicrobial screenings were done using agar diffusion technique. Antibacterial activity test was conducted by screening against six pathogens comprising both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria obtained from pharmaceutical microbiology laboratory stock. The extract was screened against 24 hour broth culture of bacteria seeded in the nutrient agar at concentrations 400, 200, 100, 50, 25, 12.5, 6.25 and 3.125 mg/ml in DMSO and incubated at 37oC, for 24 hours and measuring the inhibition zone diameter - IZD. -

Original Research Article Mid and Submontane Altitude Forests Communities on the West Hillside of Mount Bambouto (Cameroon)

1 Original Research Article 2 3 Mid and submontane altitude forests 4 communities on the West hillside of mount 5 Bambouto (Cameroon): Floristic originality and 6 comparisons ASTRACT Background and aims - Situated on the oceanic part of the Cameroon mountainous chain, the Western flank of Bambouto Mountains include the Atlantic biafran forests rich in endemic species but not well known. The objective of this work is to compare specific diversity, floristic composition and structure of two forests on this hillside. Methods - The inventories have been carried out in 18 plots of 20 m x 250 m plot established to cover all corners and centers of each forest in order to collect as many species as possible; also depending on the size of the forest block, vegetation physiognomy and altitude. Therefore, on a total area of nine hectares, all individuals with diameter at breast height ≥10 cm (dbh =1.30 m above ground) were counted. Phytodiversity has been assessed based on the usual diversity indices; these are the Shannon, Equitability and Simpson indices. The chi-square and Anova test were used to compare the data obtained. Keys results - With 168 species recorded in four hectares, the submontane forest noticeably appears richer than that of low and mid altitude (161 species in 5 hectares). Among these species, 46 are common to the two forests. The mean stands density with diameter at breast height (dbh) ≥ 10 cm recorded per hectare is 855 ± 32,7 at low and mid altitude forest and 1182 ± 38,4 at submontane forest. The diversity index, specific richness and the endemism rate values are comparable to those registered in other Central African sites. -

GRAPHIE by Cornelia D. Niles with INTRODUCTION and BOTANICAL

A BIBLIOGRAPHIC STUDY OF BEAUVOIS' AGROSTO- • GRAPHIE By Cornelia D. Niles WITH INTRODUCTION AND BOTANICAL NOTES By Aones Chase nrntODTJCTiON The Essai d?une Nouvelle Agrostographie ; ou Nouveaux Genres des Graminees; avec figures representant les Oaracteres de tous les Genres, by A. M. F. J. Palisot de Beauvois, published in 1812, is, from the standpoint of the nomenclature of grasses, a very important work, its importance being due principally to its innumerable errors, less so because of its scientific value. In this small volume 69 new genera are proposed and some 640 new species, new binomials, and new names are published. Of the 69 genera proposed 31 are to-day recognized as valid, and of the 640 names about 61 are commonly accepted. There is probably not a grass flora of any considerable region anywhere in the world that does not contain some of Beauvois' names. Many of the new names are made in such haphazard fashion that they are incorrectly listed in the Index Kewensis. There are, besides, a number of misspelled names that have found their way into botanical literature. The inaccuracies are so numerous and the cita- tions so incomplete that only a trained bibliographer* could solve the many puzzles presented. Cornelia D. Niles in connection with her work on the bibliography of grasses, maintained in the form of a card catalogue in the Grass Herbarium, worked out the basis in literature of each of these new names. The botanical problems involved, the interpretation of descriptions and figures, were worked out by Agnes Chase, who is also respon- sible for the translation and summaries from the Advertisement, Introduction, and Principles. -

Floristic Diversity Across the Cameroon Mountains: the Case of Bakossi National Park and Mt Nlonako

Floristic Diversity across the Cameroon Mountains: The Case of Bakossi National Park and Mt Nlonako i Floristic Diversity across the Cameroon Mountains The case of Bakossi National Park and Mt Nlonako Technical Report Prepared and Submitted to the Rufford Small Grant Foundation, UK By Sainge Nsanyi Moses, Ngoh Michael Lyonga and Benedicta Jailuhge Tropical Plant Exploration Group (TroPEG) Cameroon June 2018 ii To cite this work: Sainge, MN., Lyonga, NM., Jailuhge B., (2018) Floristic Diversity across the Cameroon Mountains: The case of Bakossi National Park, and Mt Nlonako. Technical Report to the Rufford Small Grant Foundation UK, by Tropical Plant Exploration Group (TroPEG) Cameroon Authors: Sainge, MN., Lyonga NM., and Jailuhge B., Title: Floristic Diversity across the Cameroon Mountains: The case of Bakossi National Park, and Mt Nlonako. Tropical Plant Exploration Group (TroPEG) Cameroon P.O. Box 18 Mundemba, Ndian division, Southwest Region [email protected]; [email protected], Tel: (+237) 677513599 iii Acknowledgement We must comment that this is the fourth grant awarded as grant number 19476-D (being the second booster RSG ) which Tropical Plant Exploration Group (TroPEG) Cameroon has received from the Rufford Small Grant (RSG) Foundation UK. We are sincerely grateful and wish to express our deep hearted thanks for the immensed support since 2011. Our sincere appreciation also goes to the Government of Cameroon through the Ministry of Scientific Research and Innovation (MINRESI) and the Ministry of Forestry and Wildlife (MINFOF) for granting authorization to carry out this work. Special gratitute goes to Dr. Mabel Nechia Wantim of the University of Buea for her contribution in developing the maps. -

Biblioqraphy & Natural History

BIBLIOQRAPHY & NATURAL HISTORY Essays presented at a Conference convened in June 1964 by Thomas R. Buckman Lawrence, Kansas 1966 University of Kansas Libraries University of Kansas Publications Library Series, 27 Copyright 1966 by the University of Kansas Libraries Library of Congress Catalog Card number: 66-64215 Printed in Lawrence, Kansas, U.S.A., by the University of Kansas Printing Service. Introduction The purpose of this group of essays and formal papers is to focus attention on some aspects of bibliography in the service of natural history, and possibly to stimulate further studies which may be of mutual usefulness to biologists and historians of science, and also to librarians and museum curators. Bibli• ography is interpreted rather broadly to include botanical illustration. Further, the intent and style of the contributions reflects the occasion—a meeting of bookmen, scientists and scholars assembled not only to discuss specific examples of the uses of books and manuscripts in the natural sciences, but also to consider some other related matters in a spirit of wit and congeniality. Thus we hope in this volume, as in the conference itself, both to inform and to please. When Edwin Wolf, 2nd, Librarian of the Library Company of Phila• delphia, and then Chairman of the Rare Books Section of the Association of College and Research Libraries, asked me to plan the Section's program for its session in Lawrence, June 25-27, 1964, we agreed immediately on a theme. With few exceptions, we noted, the bibliography of natural history has received little attention in this country, and yet it is indispensable to many biologists and to historians of the natural sciences. -

Chemical Composition, Pharmacological and Zootechnical Usefulness of Napoleonaea Vogelii Hook & Planch

American Journal of Plant Sciences, 2021, 12, 1288-1303 https://www.scirp.org/journal/ajps ISSN Online: 2158-2750 ISSN Print: 2158-2742 Zootechnical, Pharmacological Uses and Chemical Composition of Napoleonaea vogelii Hook & Planch (Lecythidaceae) in West Africa —A Review Pascal Abiodoun Olounladé1*, Christian Cocou Dansou1, Oriane Songbé1, Kisito Babatoundé Arigbo1, Tchégniho Géraldo Houménou1, André Boha Aboh1, Sylvie Mawulé Hounzangbé-Adoté2, Latifou Lagnika3 1Zootechnical Research and Livestock System Unit, Laboratory of Animal and Fisheries Science (LaSAH), National University of Agriculture (UNA), Porto-Novo, Benin 2Laboratory of Ethnopharmacology and Animal Health, Faculty of Agronomic Sciences, University of Abomey-Calavi, Cotonou, Benin 3Laboratory of Biochemistry and Bioactive Natural Substances, Faculty of Science and Technology, University of Abomey-Calavi, Cotonou, Benin How to cite this paper: Olounladé, P.A., Abstract Dansou, C.C., Songbé, O., Arigbo, K.B., Houménou, T.G., Aboh, A.B., Hounzangbé- Napoleonaea vogelii, Lecythidaceae family is a tropical evergreen shrub Adoté, S.M. and Lagnika, L. (2021) Zoo- widely distributed in the coastal regions of West African countries including technical, Pharmacological Uses and Chemi- Benin. It is a medicinal plant whose leaves and bark are of great utility in tra- cal Composition of Napoleonaea vogelii ditional medicine. Despite its importance, it is little used in ethnoveterinary Hook & Planch (Lecythidaceae) in West Africa. American Journal of Plant Sciences, medicine and its pharmacological basis in this field and especially in the 12, 1288-1303. treatment of parasitic diseases caused by Haemonchus contortus is very little https://doi.org/10.4236/ajps.2021.128090 documented. This review aims to synthesise existing data on the chemical composition, pharmacological and zootechnical usefulness of N. -

Review of Figulus Sublaevis (PALISOT DE BEAUVOIS, 1805) and F

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Koleopterologische Rundschau Jahr/Year: 2005 Band/Volume: 75_2005 Autor(en)/Author(s): Bartolozzi Luca, Monte Cinzia Artikel/Article: Review of Figulus sublaevis (PALISOT DE BEAUVOIS, 1805) and F. anthracinus KLUG, 1833 (Coleoptera: Lucanidae). 337-348 ©Wiener Coleopterologenverein (WCV), download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Koleopterologische Rundschau 75 337–348 Wien, Juni 2005 Review of Figulus sublaevis (PALISOT DE BEAUVOIS, 1805) and F. anthracinus KLUG, 1833 (Coleoptera: Lucanidae) L. BARTOLOZZI &C.MONTE Abstract Two African species of the genus Figulus Macleay, 1819 are reviewed. Figulus sublaevis (PALISOT DE BEAUVOIS, 1805) is redescribed, and compared with the closely allied F. anthracinus KLUG, 1833, from which it differs in external morphology and genitalic structures. Figulus anthracinus from Madagascar, hitherto regarded as a synonym of F. sublaevis, is resurrected as valid species (stat.res.) and its lectotype is designated. Lectotypes are also designated for F. nossibenus KRIESCHE, 1921, F. monilifer PARRY, 1862, and F. sublaevis (PALISOT DE BEAUVOIS, 1805). Key words: Coleoptera, Lucanidae, Figulus, Africa. Introduction Many authors (e.g. BURMEISTER 1847, PARRY 1873, DIDIER &SÉGUY 1953, BRINCK 1956, BENESH 1960, MAES 1992b, BARTOLOZZI &WERNER 2004) considered Figulus anthracinus KLUG, 1833 as a synonym, variety, or subspecies of F. sublaevis (PALISOT DE BEAUVOIS, 1805); other authors (e.g. PARRY 1864b, ALBERS 1885, KRAJCIK 2001, 2003) listed F. anthracinus as a distinct species. KRAJCIK (2001, 2003) considered F. anthracinus a “species incertae sedis”. During our revision of the Figulus species from continental Africa (MONTE &BARTOLOZZI 2005) we had the chance to examine many hundreds of Figulus specimens from the Afrotropical Region. -

List of Plant Species Identified in the Northern Part of the Lope Reserve, Gabon*

TROPICS 3 (3/4): 249-276 Issued March, 1994 List of Plant Species Identified in the Northern Part of the Lope Reserve, Gabon* Caroline E.G. TUTIN Centre International de Recherche Medicales de Franceville, Franceville, Gabon; Department of Biological and Molecular Sciences, University of Stirling, Scotland. Lee J. T. WHITE NYZS-The Wildlife Conservation Society, U.S.A.; Institute of Cell, Animal and Population Biology, University of Edinburgh, Scotland; Programme de Conservation et Utilisation Rationelle des Ecosystemes Forestiers d'Afrique Centrale (ECOFAC), Composante Gabon (Projet FED, CCE DG VIII). Elizabeth A. WILLIAMSON Psychology Department, University of Stirling, Scotland. Michel FERNANDEZ Centre International de Recherche Medicales de Franceville, Franceville, Gabon; Department of Biological and Molecular Sciences, University of Stirling, Scotland; Programme de Conservation et Utilisation Rationelle des Ecosystemes Forestiers d' Afrique Centrale (ECOFAC), Composante Gabon (Projet FED, CCE DG VIII). Gordon MCPHERSON Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis, Missouri, U.S.A. ABSTRACT Research on lowland gorillas (Gorilla g. gorilla) and chimpanzees (Pan t. troglodytes) began at the 'Station d'Etudes des Gorilles et Chimpanzes' in the Lope Reserve, central Gabon, in 1983 and is on-going. This paper lists 676 species of plants belonging to 91 families that occur in the 50 sq. km study area. Data on trees with diameters of 10 cm or more were collected systematically along line transects and opportunistic collections of fertile plants were made. For each plant species, the life-form, habitat preference and density (for trees recorded on transects) are listed. For plants that provide food for gorillas and chimpanzees, the part eaten is given. -

Traditional Sources of Mosquito Repellents in Southeast Nigeria

Traditional mosquito control JBiopest 5(1): 1 - 6 JBiopest 6(2):104-107 Traditional sources of mosquito repellents in southeast Nigeria Nsirim L. Edwin-Wosu, Samuel N. Okiwelu and M. Aline E. Noutcha ABSTRACT Information was obtained over two-years, in randomly-selected villages across six states viz., Abia, Akwa Ibom, Bayelsa, Cross River, Enugu and Rivers in southeast Nigeria, from key informants (herbalists) on plant species used as repellents against malaria vectors. Twenty-four species in 16 families were identified. The Verbenaceae yielded 5 species, the Meliaceae 3 species and the Malvaceae and Labiatae 2 species each. Duranta repens, Duranta plumeri (Verbenaceae) and Ocimum gratissimum (Labiatae) were the most widely used. Sida acuta (Malvaceae) was used in four states. The data were compared to plant species used in other countries across the globe as mosquito repellents; this showed that southeast Nigeria has a potential array of plant species that may be sources of plant-based malaria vector repellents. MS History: 15.9.2013 (Received)-11.11.2013 (Revised)-16.12.2013 (Accepted) Key words: Verbnaceae, Duranta spp., Ocimum gratissimum, repellents, malaria vectors. INTRODUCTION the degree of protection against biting mosquitoes or It is estimated that about 1 million deaths (range, persistence on human skin afforded by DEET 744,000-13,000,000) from the direct effects of (Peterson and Coats, 2001). Concerns with the malaria occur annually in Africa, more than 75% of safety of DEET, especially in children have resulted them are often children (Snow et al., 2001). There in the search for natural alternatives (Isman, 2006). are two main strategies for malaria management: malaria prevention (vector control, prophylaxis and Scientific literature in the past 3 decades describes potential use of vaccines) and treatment (drugs and many isolated plant secondary metabolites that blood transfusions, among others).