Leaky Slope Waves and Sea Level: Unusual Consequences of the Beta Effect Along Western Boundaries with Bottom Topography and Dissipation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Baroclinic Instability, Lecture 19

19. Baroclinic Instability In two-dimensional barotropic flow, there is an exact relationship between mass 2 streamfunction ψ and the conserved quantity, vorticity (η)given by η = ∇ ψ.The evolution of the conserved variable η in turn depends only on the spatial distribution of η andonthe flow, whichisd erivable fromψ and thus, by inverting the elliptic relation, from η itself. This strongly constrains the flow evolution and allows one to think about the flow by following η around and inverting its distribution to get the flow. In three-dimensional flow, the vorticity is a vector and is not in general con served. The appropriate conserved variable is the potential vorticity, but this is not in general invertible to find the flow, unless other constraints are provided. One such constraint is geostrophy, and a simple starting point is the set of quasi-geostrophic equations which yield the conserved and invertible quantity qp, the pseudo-potential vorticity. The same dynamical processes that yield stable and unstable Rossby waves in two-dimensional flow are responsible for waves and instability in three-dimensional baroclinic flow, though unlike the barotropic 2-D case, the three-dimensional dy namics depends on at least an approximate balance between the mass and flow fields. 97 Figure 19.1 a. The Eady model Perhaps the simplest example of an instability arising from the interaction of Rossby waves in a baroclinic flow is provided by the Eady Model, named after the British mathematician Eric Eady, who published his results in 1949. The equilibrium flow in Eady’s idealization is illustrated in Figure 19.1. -

ATMS 310 Rossby Waves Properties of Waves in the Atmosphere Waves

ATMS 310 Rossby Waves Properties of Waves in the Atmosphere Waves – Oscillations in field variables that propagate in space and time. There are several aspects of waves that we can use to characterize their nature: 1) Period – The amount of time it takes to complete one oscillation of the wave\ 2) Wavelength (λ) – Distance between two peaks of troughs 3) Amplitude – The distance between the peak and the trough of the wave 4) Phase – Where the wave is in a cycle of amplitude change For a 1-D wave moving in the x-direction, the phase is defined by: φ ),( = −υtkxtx − α (1) 2π where φ is the phase, k is the wave number = , υ = frequency of oscillation (s-1), and λ α = constant determined by the initial conditions. If the observer is moving at the phase υ speed of the wave ( c ≡ ), then the phase of the wave is constant. k For simplification purposes, we will only deal with linear sinusoidal wave motions. Dispersive vs. Non-dispersive Waves When describing the velocity of waves, a distinction must be made between the group velocity and the phase speed. The group velocity is the velocity at which the observable disturbance (energy of the wave) moves with time. The phase speed of the wave (as given above) is how fast the constant phase portion of the wave moves. A dispersive wave is one in which the pattern of the wave changes with time. In dispersive waves, the group velocity is usually different than the phase speed. A non- dispersive wave is one in which the patterns of the wave do not change with time as the wave propagates (“rigid” wave). -

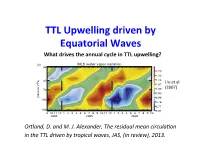

TTL Upwelling Driven by Equatorial Waves

TTL Upwelling driven by Equatorial Waves L09804 LIUWhat drives the annual cycle in TTL upwelling? ET AL.: START OF WATER VAPOR AND CO TAPE RECORDERS L09804 Liu et al. (2007) Ortland, D. and M. J. Alexander, The residual mean circula8on in the TTL driven by tropical waves, JAS, (in review), 2013. Figure 1. (a) Seasonal variation of 10°N–10°S mean EOS MLS water vapor after dividing by the mean value at each level. (b) Seasonal variation of 10°N–10°S EOS MLS CO after dividing by the mean value at each level. represented in two principal ways. The first is by the area of [8]ConcentrationsofwatervaporandCOnearthe clouds with low infrared brightness temperatures [Gettelman tropical tropopause are available from retrievals of EOS et al.,2002;Massie et al.,2002;Liu et al.,2007].Thesecond MLS measurements [Livesey et al.,2005,2006].Monthly is by the area of radar echoes reaching the tropopause mean water vapor and CO mixing ratios at 146 hPa and [Alcala and Dessler,2002;Liu and Zipser, 2005]. In this 100 hPa in the 10°N–10°Sand10° longitude boxes are study, we examine the areas of clouds that have TRMM calculated from one full year (2005) of version 1.5 MLS Visible and Infrared Scanner (VIRS) 10.8 mmbrightness retrievals. In this work, all MLS data are processed with temperatures colder than 210 K, and the area of 20 dBZ requirements described by Livesey et al. [2005]. Tropopause echoes at 14 km measured by the TRMM Precipitation temperature is averaged from the 2.5° resolution NCEP Radar (PR). -

The Counter-Propagating Rossby-Wave Perspective on Baroclinic Instability

Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. (2005), 131, pp. 1393–1424 doi: 10.1256/qj.04.22 The counter-propagating Rossby-wave perspective on baroclinic instability. Part III: Primitive-equation disturbances on the sphere 1∗ 2 1 3 CORE By J. METHVEN , E. HEIFETZ , B. J. HOSKINS and C. H. BISHOPMetadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk 1 Provided by Central Archive at the University of Reading University of Reading, UK 2Tel-Aviv University, Israel 3Naval Research Laboratories/UCAR, Monterey, USA (Received 16 February 2004; revised 28 September 2004) SUMMARY Baroclinic instability of perturbations described by the linearized primitive equations, growing on steady zonal jets on the sphere, can be understood in terms of the interaction of pairs of counter-propagating Rossby waves (CRWs). The CRWs can be viewed as the basic components of the dynamical system where the Hamil- tonian is the pseudoenergy and each CRW has a zonal coordinate and pseudomomentum. The theory holds for adiabatic frictionless flow to the extent that truncated forms of pseudomomentum and pseudoenergy are globally conserved. These forms focus attention on Rossby wave activity. Normal mode (NM) dispersion relations for realistic jets are explained in terms of the two CRWs associated with each unstable NM pair. Although derived from the NMs, CRWs have the conceptual advantage that their structure is zonally untilted, and can be anticipated given only the basic state. Moreover, their zonal propagation, phase-locking and mutual interaction can all be understood by ‘PV-thinking’ applied at only two ‘home-bases’— potential vorticity (PV) anomalies at one home-base induce circulation anomalies, both locally and at the other home-base, which in turn can advect the PV gradient and modify PV anomalies there. -

MAST602: Introduction to Physical Oceanography (Andreas Münchow) (Closed Book In-Class Rossby Wave Exercise, Oct.-21, 2008)

MAST602: Introduction to Physical Oceanography (Andreas Münchow) (Closed book in-class Rossby Wave Exercise, Oct.-21, 2008) In a series of papers published in the 1930ies Carl-Gustaf Rossby introduced a strange new wave form whose existence has not been confirmed observationally until the late 1990ies. A debate is presently raging if and how these waves may impact ecosystems in the ocean, e.g., “Killworth et al., 2003: Physical and biological mechanisms for planetary waves observed in satellite-derived chlorophyll, J. Geophys. Res.” and “Dandonneau et al., 2003: Oceanic Rossby waves acting as a “Hay Rake” for ecosystem floating by- products, Science” as well as a flurry of comments generated by these papers. These peculiar waves originate from a linear balance between local acceleration, Coriolis acceleration, and pressure gradients as well as continuity of mass, that is, East-west momentum balance: ∂u/∂t – fv = -g ∂η/∂x North-south momentum balance: ∂v/∂t + fu = -g ∂η/∂y Continuity: ∂η/∂t + H (∂u/∂x+∂v/∂y) = 0 where the Coriolis parameter f = 2 Ω sin(latitude) is no longer a constant, but is approximated locally as f ≈ f0 + βy. The rotational rate of the earth is Ω=2π/day and at the -4 -1 -11 -1 -1 latitude of Lewes, DE (39N), f0~0.9×10 s and β~2×10 m s . A number of peculiar properties can be inferred from its dispersion relation: σ = − β κ / (κ2+l2+R-2) where σ is the wave frequency, κ is the wave number in the east-west direction, l is the wave number in the north-south direction, β is a constant (the so-called beta-parameter 1/2 that incorporates Coriolis effects that changes with latitude), and R=(g’H) /f0 is a constant (the so-called Rossby radius of deformation, the same as the lateral decay scale of the Kelvin wave, where g’~9.81×10-3m/s2 is the constant of “reduced” gravity, and H~1000 m is the depth of the pycnocline (density interface). -

El Niño: the Ocean in Climate El Niño: the Ocean in Climate

El Niño: The ocean in climate We live in the atmosphere: where is it sensitive to the ocean? ➞ The tropics! El Niño is the most spectacular short-term climate oscillation. It affects weather around the world, and illustrates the many aspects of O-A interaction Most of the poleward heat transport is by the atmosphere First hint that this may all be myth comes from using observations to estimate atmosphere and ocean(except heat in the tropics) transports Ocean and atmosphere heat transports Heat transport is poleward in &'()*('&+,-.,/01,2%""34,-5.67/.-5,89:,;9:.<=/:>,<-/.,.:/;5?9:.5 # both ocean and atmosphere: )D(B,E('1,F&G (DGCH,E('1,F&G )D(B,E('1,ID(F) Atmosphere (DGCH,E('1,ID(F) The role of the O-A system is $ Net radiation at Atmosphere (line) to move excess heat from the top of atmosphere tropics to the poles, where it Ocean (Dashed) Ocean = divergence of % is radiated to space. (AHT + OHT) " BC Net radiation Northward transport (PW) !% from satellites, AHT from weather obs !$ and models, OHT from residual Trenberth et al (2001) !# 80°S!!" 60°S!#" 40°S!$" 20°S!%" 0°" 20°N%" 40°N$" 60°N#" 80°N!" @/.6.A>- Most of the poleward transport occurs in mid-latitude winter storms near 40°S/N. Only in the tropics is the ocean really important. Much recent interest in the “global conveyor belt” But the timescales are very slow Does the Gulf Stream warm Europe? An example of the (largely) passive effect of the ocean Why is Ireland warmer than Labrador in winter? Because of need to conserve angular momentum, Rockies force a stationary wave in the westerlies with northerly flow (cooling) over eastern N. -

Topographic Rossby Waves in the Arctic Ocean's Beaufort Gyre

Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans RESEARCH ARTICLE Topographic Rossby Waves in the Arctic Ocean’s Beaufort Gyre 10.1029/2018JC014233 Bowen Zhao1 and Mary-Louise Timmermans1 Special Section: Forum for Arctic Modeling 1Department of Geology & Geophysics, Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA and Observational Synthesis (FAMOS) 2: Beaufort Gyre phenomenon Abstract A 5-year long time series of temperature and horizontal velocity in the Arctic Ocean’s Key Points: Beaufort Gyre is analyzed with the aim of understanding the mechanism driving the observed variability • Beaufort Gyre mooring on timescales of tens of days (i.e., subinertial). We employ a coherency/phase analysis on the temperature measurements of velocity and and horizontal velocity signals, which indicates that subinertial temperature variations arise from vertical temperature are analyzed for subinertial signal excursions of the water column that are driven by horizontal motions across the sloping seafloor. The • Observations are consistent vertical displacements of the water column (recorded by the temperature signal) show a bottom-intensified with topographic Rossby waves signature (i.e., decay toward the surface), while horizontal velocity anomalies are approximately barotropic propagating on sloping seafloor • Topographic Rossby waves play a role below the main halocline. We show that the different characteristics in vertical and horizontal velocities are in Beaufort Gyre stabilization consistent with topographic Rossby wave theory in the limit of weak vertical decay. In essence, a linearly decaying vertical velocity profile implies that the whole water column is stretched/squashed uniformly with Correspondence to: depth when water moves horizontally across the bottom slope. Thus, for the uniform stratification of the B. -

Lecture 5: the Spectrum of Free Waves Possible Along Coasts

Lecture 5: The Spectrum of Free Waves Possible along Coasts Myrl Hendershott 1 Introduction In this lecture we discuss the spectrum of free waves that are possible along the straight coast in shallow water approximation. 2 Linearized shallow water equations The linearized shallow water equations(LSW) are u fv = gζ ; (1) t − − x v + fu = gζ ; (2) t − y ζt + (uD)x + (vD)y = 0: (3) where D; η are depth and free surface elevations respectively. 3 Kelvin Waves Kelvin waves require the support of a lateral boundary and it occurs in the ocean where it can travel along coastlines. Consider the case when u = 0 in the linearized shallow water equations with constant depth. In this case we have that the Coriolis force in the offshore direction is balanced by the pressure gradient towards the coast and the acceleration in the Longshore direction is gravitational. Substituting u = 0 in equation (1) through (3) (assuming constant depth D) gives fv = gζx; (4) v = gζ ; (5) t − y ζt + Dvy = 0; (6) eliminating ζ between equation (4) through equation (6) gives vtt = (gD)vyy: (7) The general wave solution can be written as v = V (x; y + ct) + V (x; y ct); (8) 1 2 − 63 2 where c = gD and V1; V2 are arbitrary functions. Now note that ζ satisfies ζtt = (gD)ζyy: (9) Hence we can try ζ = AV (x; y + ct) + BV (x; y ct). From equation (4) or equation (5) 1 2 − we get A = H=g , b = H=g. V and V can be determined as follows. -

Detection of Rossby Wave Breaking and Its Response to Shifts of the Midlatitude Jet with Climate Change

JOURNAL OF GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCH, VOL. ???, XXXX, DOI:10.1029/, Detection of Rossby wave breaking and its response to shifts of the midlatitude jet with climate change 1 1 Elizabeth A. Barnes and Dennis L. Hartmann Elizabeth A. Barnes, Department of Atmospheric Sciences, University Washington, Box 351640, Seattle, WA 98195. ([email protected]) Dennis L. Hartmann, Department of Atmospheric Sciences, University Washington, Box 351640, Seattle, WA 98195. ([email protected]) 1Department of Atmospheric Science, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, USA. D R A F T March 5, 2012, 10:18am D R A F T X-2 BARNES AND HARTMANN: WAVE BREAKING AND CLIMATE CHANGE Abstract. A Rossby wave breaking identification method is presented which searches for overturning of absolute vorticity contours on pressure sur- faces. The results are compared to those from an analysis of isentropic po- tential vorticity, and it is demonstrated that both yield similar wave break- ing distributions. As absolute vorticity is easily obtained from most model output, we present wave breaking frequency distributions from the ERA-Interim data set, thirteen general circulation models (GCMs) and a barotropic model. We demonstrate that a poleward shift of the Southern Hemisphere midlat- itude jet is accompanied by a decrease in poleward wave breaking in both the barotropic model and all GCMs across three climate forcing scenarios. In addition, it is shown that while anticyclonic wave breaking shifts poleward with the jet, cyclonic wave breaking shifts less than half as much and reaches a poleward limit near 60 degrees S. Comparison of the observed distribution of Southern Hemisphere wave breaking with those from the GCMs suggests that wave breaking on the poleward flank of the jet has already reached its poleward limit and will likely become less frequent if the jet migrates any further poleward with climate change. -

Geophysics Fluid Dynamics (ESS228)

Geophysics Fluid Dynamics (ESS228) . Course Time Lectures: Tu, Th 09:30-10:50 Discussion: 3315 Croul Hall . Text Book J. R. Holton, "An introduction to Dynamic Meteorology", Academic Press (Ch. 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 11). Adrian E. Gill, "Atmosphere-Ocean Dynamics", Academic Press (Ch. 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12). Grade Homework (30%), Midterm (35%), Final (35%) . Homework Issued and due every Thursday ESS227 Prof. Jin-Yi Yu Syllabus ESS227 Prof. Jin-Yi Yu Dynamics and Kinematics • Kinematics: The term kinematics means motion. Kinematics is the study of motion without regard for the cause. • Dynamics: On the other hand, dynamics is the study of the causes of motion. This course discusses the physical laws that govern atmosphere/ocean motions. ESS228 Prof. Jin-Yi Yu Geophysical Fluid Dynamics the study of the causes of motion causes: solar radiation competes with gravity distributions of T and motions governed by conservation laws ESS227 Prof. Jin-Yi Yu Newton’s 2nd Law of Motion Newton’s 2nd Law of Momentum = absolute velocity viewed in an inertial system = rate of change of Ua following the motion in an inertial system • The conservation law for momentum (Newton’s second law of motion) relates the rate of change of the absolute momentum following the motion in an inertial reference frame to the sum of the forces acting on the fluid. ESS228 Prof. Jin-Yi Yu Conservation of Mass • The mathematical relationship that expresses conservation of mass for a fluid is called the continuity equation. (mass divergence form) (velocity divergence form) ESS228 Prof. Jin-Yi Yu The First Law of Thermodynamics • This law states that (1) heat is a form of energy that (2) its conversion into other forms of energy is such that total energy is conserved. -

Influence of Rossby Waves on Primary Production from a Coupled Physical

Ocean Sci., 4, 199–213, 2008 www.ocean-sci.net/4/199/2008/ Ocean Science © Author(s) 2008. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. Influence of Rossby waves on primary production from a coupled physical-biogeochemical model in the North Atlantic Ocean G. Charria1,2, I. Dadou1, P. Cipollini2, M. Drevillon´ 3, and V. Garc¸on1 1Laboratoire d’Etudes en Geophysique´ et Oceanographie´ Spatiales, UMR5566/CNRS, Toulouse, France 2National Oceanography Centre, Southampton, United Kingdom 3CERFACS, MERCATOR-Ocean,´ Toulouse, France Received: 30 October 2007 – Published in Ocean Sci. Discuss.: 29 November 2007 Revised: 9 July 2008 – Accepted: 1 August 2008 – Published: 1 September 2008 Abstract. Rossby waves appear to have a clear signature on actions. Based on remotely sensed data and/or coupled surface chlorophyll concentrations which can be explained physical/biogeochemical modelling, several studies inves- by a combination of vertical and horizontal mechanisms. In tigated the coupled physical/biogeochemical mechanisms this study, we investigate the role of the different physical which might be involved (e.g. Charria et al., 2003, 2006a; processes in the north Atlantic to explain the surface chloro- Killworth et al., 2004). Three main processes were sug- phyll signatures and the consequences on primary produc- gested: (1) the upwelling mechanism associated with nutri- tion, using a 3-D coupled physical/biogeochemical model for ent injection (Cipollini et al., 2001; Uz et al., 2001; Siegel, the year 1998. 2001), (2) the uplifting of a deep chlorophyll maximum to- The analysis at 20 given latitudes, mainly located in the wards the surface (Cipollini et al., 2001; Kawamiya and Os- subtropical gyre, where Rossby waves are strongly correlated chlies, 2001; Charria et al., 2003), and (3) the meridional with a surface chlorophyll signature, shows the important advection of chlorophyll by geostrophic currents associated contribution of horizontal advection and of vertical advec- with baroclinic Rossby waves (Killworth et al., 2004). -

Though the Ocean Is Heavily Damped System for the Long-Period Tides, Non-Equilibrium Features Can Be Found. Short Rossby Wave

測 地 学 会 誌,第47巻,第1号 Journal of the Geodetic Society of Japan (2001),551-557頁 Vol.47, No.1, (2001), pp.551-557 Non-equilibrium Characteristics of the Long-Period Ocean Tides from Dynamics and Energetics Takashi Takanezawa*, Koji Matsumoto, Masatsugu Ooe and Isao Naito National Astronomical Observatory, 2-12 Hoshigaoka-cho, Mizusawa-shi, Iwate-ken 023-0861, Japan (Received October 3, 2000; Revised February 7, 2001; Accepted February 15, 2001) Abstract Dynamics and energetics of the long-period ocean tides are investigated using a global barotropic ocean model. Estimated oceanic Qs of the long-period tides are about 3, which show that the ocean is heavily damped system. Some far-reaching tidal energy fluxes, however, exist. Equatorial eastward flux from the coast of South Africa to the Pacific especially stands out. LFrom the point of view of wave dynam ics, contrary to the tidal energy flux in the tropics, wave's energy propagates in the westward direction. With the relation between the energy flux of wave and group ve locity, the westward direction shows that the energy flux corresponds to long Rossby wave. Moreover, this relation clearly shows existence of short Rossby waves in the mid latitudes. LFrom the point of view of planetary scale dynamics, zonally averages of dy namic tide and tidal currents show existence of global non-equilibrium response, which is similar to a particular solution of constant depth ocean. The global response may corresponds to the deviation from the equilibrium tide in zonally averaged admittance, which is found in the analysis of altimeter data.