Posthumanism in Latin American Science Fiction Between 1960-1999

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Science Fiction in Argentina: Technologies of the Text in A

Revised Pages Science Fiction in Argentina Revised Pages DIGITALCULTUREBOOKS, an imprint of the University of Michigan Press, is dedicated to publishing work in new media studies and the emerging field of digital humanities. Revised Pages Science Fiction in Argentina Technologies of the Text in a Material Multiverse Joanna Page University of Michigan Press Ann Arbor Revised Pages Copyright © 2016 by Joanna Page Some rights reserved This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution- Noncommercial- No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 171 Second Street, Suite 300, San Francisco, California, 94105, USA. Published in the United States of America by the University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid- free paper 2019 2018 2017 2016 4 3 2 1 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Page, Joanna, 1974– author. Title: Science fiction in Argentina : technologies of the text in a material multiverse / Joanna Page. Description: Ann Arbor : University of Michigan Press, [2016] | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2015044531| ISBN 9780472073108 (hardback : acid- free paper) | ISBN 9780472053100 (paperback : acid- free paper) | ISBN 9780472121878 (e- book) Subjects: LCSH: Science fiction, Argentine— History and criticism. | Literature and technology— Argentina. | Fantasy fiction, Argentine— History and criticism. | BISAC: LITERARY CRITICISM / Science Fiction & Fantasy. | LITERARY CRITICISM / Caribbean & Latin American. Classification: LCC PQ7707.S34 P34 2016 | DDC 860.9/35882— dc23 LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015044531 http://dx.doi.org/10.3998/dcbooks.13607062.0001.001 Revised Pages To my brother, who came into this world to disrupt my neat ordering of it, a talent I now admire. -

2015, Volume 8

V O L U M E 8 2015 D E PAUL UNIVERSITY Creating Knowledge THE LAS JOURNAL OF UNDERGRADUATE SCHOLARSHIP CREATING KNOWLEDGE The LAS Journal of Undergraduate Scholarship 2015 EDITOR Warren C. Schultz ART JURORS Adam Schreiber, Coordinator Laura Kina Steve Harp COPY EDITORS Stephanie Klein Rachel Pomeroy Anastasia Sasewich TABLE OF CONTENTS 6 Foreword, by Interim Dean Lucy Rinehart, PhD STUDENT RESEARCH 8 S. Clelia Sweeney Probing the Public Wound: The Serial Killer Character in True- Crime Media (American Studies Program) 18 Claire Potter Key Progressions: An Examination of Current Student Perspectives of Music School (Department of Anthropology) 32 Jeff Gwizdalski Effect of the Affordable Care Act on Insurance Coverage for Young Adults (Department of Economics) 40 Sam Okrasinski “The Difference of Woman’s Destiny”: Female Friendships as the Element of Change in Jane Austen’s Emma (Department of English) 48 Anna Fechtor Les Musulmans LGBTQ en Europe Occidentale : une communauté non reconnue (French Program, Department of Modern Languages) 58 Marc Zaparaniuk Brazil: A Stadium All Its Own (Department of Geography) 68 Erin Clancy Authority in Stone: Forging the New Jerusalem in Ethiopia (Department of the History of Art and Architecture) 76 Kristin Masterson Emmett J. Scott’s “Official History” of the African-American Experience in World War One: Negotiating Race on the National and International Stage (Department of History) 84 Lizbeth Sanchez Heroes and Victims: The Strategic Mobilization of Mothers during the 1980s Contra War (Department -

![Robots: Everywhere Around Us [A Dream Coming True]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3084/robots-everywhere-around-us-a-dream-coming-true-233084.webp)

Robots: Everywhere Around Us [A Dream Coming True]

Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) Robotics & Automation Society Egypt Chapter Robots: Everywhere around us [A Dream Coming True] Prepared by: Dr. Alaa Khamis, Egypt Chapter Chair Presented by: Eng. Omar Mahmoud http://www.ras-egypt.org/ MUSES_SECRET:© Dr. Alaa Khamis, ORF IEEE-RE RAS Project – Egypt - Chapter© PAMI – Research Robots: Around Group –us University Everywhere of Waterloo 1/221 Outline • IEEE RAS – Egypt Chapter MUSES_SECRET:• What ORFis- REa Project Robot? - © PAMI Research Group – University of Waterloo • What is Robotics? • Science Fiction • Science Facts • Robots Today • Robots’ Future MUSES_SECRET:© Dr. Alaa Khamis, ORF IEEE-RE RAS Project – Egypt - Chapter© PAMI – Research Robots: Around Group –us University Everywhere of Waterloo 2/222 Outline • IEEE RAS – Egypt Chapter MUSES_SECRET:• What ORFis- REa Project Robot? - © PAMI Research Group – University of Waterloo • What is Robotics? • Science Fiction • Science Facts • Robots Today • Robots’ Future MUSES_SECRET:© Dr. Alaa Khamis, ORF IEEE-RE RAS Project – Egypt - Chapter© PAMI – Research Robots: Around Group –us University Everywhere of Waterloo 3/223 IEEE RAS – Egypt Chapter Established in Sept. 2011 to become the meeting place of choice for the robotics and automation community in Egypt. MUSES_SECRET:© Dr. Alaa Khamis, ORF IEEE-RE RAS Project – Egypt - Chapter© PAMI – Research Robots: Around Group –us University Everywhere of Waterloo 4/224 IEEE RAS – Egypt Chapter • Conferences & Workshops • Seminars & Webinars • Free Courses • Robotic Competitions MUSES_SECRET:© Dr. Alaa Khamis, ORF IEEE-RE RAS Project – Egypt - Chapter© PAMI – Research Robots: Around Group –us University Everywhere of Waterloo 5/225 Conferences & Workshops MUSES_SECRET:© Dr. Alaa Khamis, ORF IEEE-RE RAS Project – Egypt - Chapter© PAMI – Research Robots: Around Group –us University Everywhere of Waterloo 6/226 ICET 2012 http://landminefree.org/ http://www.icet-guc.org/2012/ MUSES_SECRET:© Dr. -

Oil Workers' Rights Will Not Be Undermined, Minister Says

SUBSCRIPTION WEDNESDAY, JUNE 22, 2016 RAMADAN 17, 1437 AH www.kuwaittimes.net Alghanim to More than 700 England Iran: Bahrain Ramadan TImings expand Wendy’s doctors killed progress after ‘will pay price’ Emsak: 03:04 brand into Saudi in Syrian war Slovakia draw for crackdown Fajer: 03:14 Shrooq: 04:48 Dohr: 11:50 Asr: 15:24 Maghreb: 18:51 2 7 19 13 Eshaa: 20:23 Oil workers’ rights will not Min 33º Max 47º be undermined, Minister says High Tide 02:55 & 12:12 Low Tide MPs call for new strategy for Kuwaiti investments 06:55 & 19:57 40 PAGES NO: 16912 150 FILS KUWAIT: Finance Minister and Acting Oil Minister Anas Ramadan Kareem Al-Saleh said yesterday the government will not under- mine the rights of the workers in the oil sector who Social dimension went on a three-day strike in April to demand their rights. The minister said that the oil sector proposed a of fasting, Ramadan number of initiatives to cut spending in light of the sharp drop in oil prices and the workers went on strike By Hatem Basha even before these initiatives were applied. ost people view Ramadan as a sublime peri- He said the Ministry is currently in talks with the od, where every Muslim experience sublime workers about the initiatives but insisted that the Mfeelings as hearts soften and souls tran- rights of the workers will not be touched. The minis- scend the worldly pleasures. Another dimension that ter’s comments came in response to remarks made by is often overlooked is the social dimension of fasting. -

Friday Prime Time, April 17 4 P.M

April 17 - 23, 2009 SPANISH FORK CABLE GUIDE 9 Friday Prime Time, April 17 4 P.M. 4:30 5 P.M. 5:30 6 P.M. 6:30 7 P.M. 7:30 8 P.M. 8:30 9 P.M. 9:30 10 P.M. 10:30 11 P.M. 11:30 BASIC CABLE Oprah Winfrey Å 4 News (N) Å CBS Evening News (N) Å Entertainment Ghost Whisperer “Save Our Flashpoint “First in Line” ’ NUMB3RS “Jack of All Trades” News (N) Å (10:35) Late Show With David Late Late Show KUTV 2 News-Couric Tonight Souls” ’ Å 4 Å 4 ’ Å 4 Letterman (N) ’ 4 KJZZ 3The People’s Court (N) 4 The Insider 4 Frasier ’ 4 Friends ’ 4 Friends 5 Fortune Jeopardy! 3 Dr. Phil ’ Å 4 News (N) Å Scrubs ’ 5 Scrubs ’ 5 Entertain The Insider 4 The Ellen DeGeneres Show (N) News (N) World News- News (N) Two and a Half Wife Swap “Burroughs/Padovan- Supernanny “DeMello Family” 20/20 ’ Å 4 News (N) (10:35) Night- Access Holly- (11:36) Extra KTVX 4’ Å 3 Gibson Men 5 Hickman” (N) ’ 4 (N) ’ Å line (N) 3 wood (N) 4 (N) Å 4 News (N) Å News (N) Å News (N) Å NBC Nightly News (N) Å News (N) Å Howie Do It Howie Do It Dateline NBC A police of cer looks into the disappearance of a News (N) Å (10:35) The Tonight Show With Late Night- KSL 5 News (N) 3 (N) ’ Å (N) ’ Å Michigan woman. (N) ’ Å Jay Leno ’ Å 5 Jimmy Fallon TBS 6Raymond Friends ’ 5 Seinfeld ’ 4 Seinfeld ’ 4 Family Guy 5 Family Guy 5 ‘Happy Gilmore’ (PG-13, ’96) ›› Adam Sandler. -

Cybernetic Human HRP-4C: a Humanoid Robot with Human-Like Proportions

Cybernetic Human HRP-4C: A humanoid robot with human-like proportions Shuuji KAJITA, Kenji KANEKO, Fumio KANEIRO, Kensuke HARADA, Mitsuharu MORISAWA, Shin’ichiro NAKAOKA, Kanako MIURA, Kiyoshi FUJIWARA, Ee Sian NEO, Isao HARA, Kazuhito YOKOI, Hirohisa HIRUKAWA Abstract Cybernetic human HRP-4C is a humanoid robot whose body dimensions were designed to match the average Japanese young female. In this paper, we ex- plain the aim of the development, realization of human-like shape and dimensions, research to realize human-like motion and interactions using speech recognition. 1 Introduction Cybernetics studies the dynamics of information as a common principle of com- plex systems which have goals or purposes. The systems can be machines, animals or a social systems, therefore, cybernetics is multidiciplinary from its nature. Since Norbert Wiener advocated the concept in his book in 1948[1], the term has widely spreaded into academic and pop culture. At present, cybernetics has diverged into robotics, control theory, artificial intelligence and many other research fields, how- ever, the original unified concept has not yet lost its glory. Robotics is one of the biggest streams that branched out from cybernetics, and its goal is to create a useful system by combining mechanical devices with information technology. From a practical point of view, a robot does not have to be humanoid; nevertheless we believe the concept of cybernetics can justify the research of hu- manoid robots for it can be an effective hub of multidiciplinary research. WABOT-1, -

Manuel De Pedrolo's "Mecanoscrit"

Alambique. Revista académica de ciencia ficción y fantasía / Jornal acadêmico de ficção científica e fantasía Volume 4 Issue 2 Manuel de Pedrolo's "Typescript Article 3 of the Second Origin" Political Wishful Thinking versus the Shape of Things to Come: Manuel de Pedrolo’s "Mecanoscrit" and “Los últimos días” by Àlex and David Pastor Pere Gallardo Torrano Universitat Rovira i Virgili, Tarragona, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/alambique Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, European Languages and Societies Commons, Other Languages, Societies, and Cultures Commons, and the Other Spanish and Portuguese Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Gallardo Torrano, Pere (2017) "Political Wishful Thinking versus the Shape of Things to Come: Manuel de Pedrolo’s "Mecanoscrit" and “Los últimos días” by Àlex and David Pastor," Alambique. Revista académica de ciencia ficción y fantasía / Jornal acadêmico de ficção científica e fantasía: Vol. 4 : Iss. 2 , Article 3. https://www.doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.5038/2167-6577.4.2.3 Available at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/alambique/vol4/iss2/3 Authors retain copyright of their material under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 License. Gallardo Torrano: Catalan Apocalypse: Pedrolo versus the Pastor Brothers The present Catalan cultural and linguistic revival is not a new phenomenon. Catalan language and culture is as old as the better-known Spanish/Castilian is, with which it has shared a part of the Iberian Peninsula for centuries. The 19th century brought about a nationalist revival in many European states, and many stateless nations came into the limelight. -

Hacia Un Cuarto Cine: Violencia, Marginalidad, Memoria Y Nuevos Escenarios Globales En Ventiún Películas Latinoamericanas

HACIA UN CUARTO CINE: VIOLENCIA, MARGINALIDAD, MEMORIA Y NUEVOS ESCENARIOS GLOBALES EN VENTIÚN PELÍCULAS LATINOAMERICANAS by Jorge Zavaleta Balarezo Bachiller en Lingüística y Literatura Hispánicas, Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú, 2005 Master in Arts in Hispanic Languages and Literatures, University of Pittsburgh, 2008 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Ph.D. in Hispanic Languages and Literatures i University of Pittsburgh 2011 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Jorge Zavaleta Balarezo It was defended on December 7, 2011 and approved by John Beverley, Distinguished Professor, Hispanic Languages and Literatures Hermann Herlinghaus, Professor, Hispanic Languages and Literatures Aníbal Pérez-Liñán, Associate Professor, Political Science Dissertation Advisors: Elizabeth Monasterios, Associate Professor, Hispanic Languages and Literatures and Juan Duchesne-Winter, Professor, Hispanic Languages and Literatures ii HACIA UN CUARTO CINE: VIOLENCIA, MARGINALIDAD, MEMORIA Y NUEVOS ESCENARIOS GLOBALES EN VEINTIÚN PELÍCULAS LATINOAMERICANAS Jorge Zavaleta Balarezo, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2011 Contemporary Latin American cinema features a series of realist portraits and testimonies, in which young filmmakers develop their own visions of the new conditions of life on the continent. This dissertation looks at these specific cinematic visions of beings who survive on the edges of marginality and violence. The dissertation is articulated specifically along topics representing critical approaches to movies produced in Argentina, Colombia, Brazil, Peru, Bolivia, Chile and Mexico. The works of a new generation of filmmakers including Alejandro González Iñárritu, Lucrecia Martel, Israel Adrián Caetano, Carlos Reygadas and Fernando Meirelles uncover a series of erosions of the social composition of the countries where these directors live. -

Eeuu Lucha Libre

EEUU LUCHA LIBRE Profesionales detrás de la famosa máscara de la lucha libre mexicana 06 de marzo de 2012 Nueva York, 6 mar (EFE).- Un abogado y un experto en sistemas de computadoras están detrás de las máscaras de famosos luchadores que participarán de una gira nacional, que permitirá a inmigrantes disfrutar de sus ídolos de ese legendario deporte que nació en México. "Masked Warriors Live" es el gira que recorrerá más de una docena de principales ciudades de población hispana en EE.UU. con quince luchadores, el 90 por ciento de ellos mexicanos, que subirán al cuadrilátero mostrando con orgullo las máscaras que caracterizan este deporte, que nació en su país hace 75 años. Algunos de los luchadores más conocidos, Blue Demon hijo, Lizmark hijo y Latin Lover, entre otros, viajarán desde México, donde residen, para participar de la gira, que según "Lucha Libre USA" que la organiza, es la primera de magnitud que han realizado en los dos años de creada de la compañía, que promueve el tipo de lucha libre mexicana. La lista de otros conocidos mexicanos incluye a Súper Nova, Pequeño Halloween, El oriental, Chavo Guerrero y L.A. Park, que por generaciones se han dedicado a la lucha libre. La gira comenzará el próximo 23 de marzo en Reno, Nevada, de donde se trasladará a California y Texas, y en cada ciudad contarán con luchadores locales como invitados, explicó Alex Abrahantes, de Lucha Libre USA. "El 70 por ciento de las familias que acuden son latinas, vienen padres, hijos y abuelos. Es como una religión en México y acá en EE.UU. -

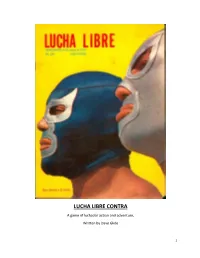

Lucha Libre Contra

LUCHA LIBRE CONTRA A game of luchador action and adventure, Written by Dave Glide 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 3 Agendas & Principles; GM Moves; World & Adventures CHARACTER CREATION ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 9 Concept; Stats; Roles; Moves; History; Fatigue; Glory; Experience & Reputation Levels CHARACTER ROLES ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 13 Tecnico; Rudo; Monstruo; High-Flyer; Extrema; Exotico GENERICO MOVES ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 19 Rookie; Journeyman; Professional; Champion; Legend ADVANCED CHARACTER OPTIONS ………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 25 Starting Above “Rookie;” Cross-Role Moves; Alternative Characters; Character Creation Example TAKING ACTION …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 29 Combat & Non-Combat Moves LUCHA COMBAT and CULTURE NOTES ………………………………………………………………………………………………… 41 Match Rules; Lucha Terminology; Optional Rules ENEMIES OF THE LUCHADORES …………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 48 Monster Stats; Henchman; Mythology and Death Traps SAMPLE VILLAINS ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 52 SAMPLE DEATH TRAPS ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 56 INSPIRATION ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 58 FINAL WORD ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 59 2 THE WORLD OF LUCHA LIBRE CONTRA In Lucha Libre Contra, players take on heroes. Young fans could thrill to El Santo’s the role of luchadores: masked Mexican adventures in -

NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC Program Schedule June(Weekly) MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT SUN 4.11.18.25 5.12.19.26 6.13.20.27 7.14.21.28 1.8.15.22.29 2.9.16.23.30 3.10.17.24

NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC Program Schedule June(weekly) MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT SUN 4.11.18.25 5.12.19.26 6.13.20.27 7.14.21.28 1.8.15.22.29 2.9.16.23.30 3.10.17.24 400 400 Hitler's Last Year、 Family Guns、 Family Guns、 WW2 Hell Under the Sea、 Underworld, Inc. Nazi Attack On America、 Nazi World War Weird Apocalypse World War I、 Apocalypse: The Second World My Fighting Season One Strange Rock Long Road Home America's Great War 1917-1918 War 430 430 500 500 Time Scanners、Return From The Dead、Into The Crystal Cave、Viking Apocalypse、 Borneo's Secret Kingdom Chain of Command Hitler's Jurassic Monsters、Secrets of Christ's Tomb: Explorer Special、Invaders、 →Wild Namibia →I Wouldn't Go In There Mystery of The Disappearing Skyjacker、Paranatural II、Secret History of UFO's、Roswell UFO Secrets、Invasion Earth →Wild Botswana: Lion Brotherhood 530 530 600 information 600 630 Brain Games 4、Is It Real?、Mad Scientists 630 700 700 Return of The Lion、Game Of Lions、Caught in the Act V、 Planet Carnivore、Blood Rivals: Lion vs. Buffalo、Brutal Killers、 Dr. K's Exotic Animal ER Cat Wars: Lion vs. Cheetah、Lion vs. Giraffe、Superpride、Blood Rivals: Hippo V. Lion、 Supercar Megabuild2 Car S.O.S.Ⅱ Season 3 Attack of The Big Cats、Big Cat Games、The Jungle King Compilation →Shido Nakamura's unexpected trip by Golf GTI Dynamic →CAR S.O.S.Ⅳ Test broadcasting Program(22nd) 730 730 800 800 Two Tales of China、 CAR S.O.S.Ⅲ Big, Bigger, Biggest 2、Nazi World War Weird、Das Reich - Hitler's Death Squad、Chasing UFOs China From Above、 Megafactories →Shido Nakamura's unexpected trip by Golf GTI Dynamic Maritime China 830 830 900 information 900 930 930 Cosmos: A Spacetime Odyssey、Moon Landings Declassified、Roswell UFO Secrets、 Survive the Wild Wicked Tuna 7 Genius(18h ~11:00) 1000 1000 1030 information 1030 Pope vs. -

Sunday Morning Grid 12/25/11

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 12/25/11 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning (N) Å Face/Nation A Gospel Christmas NCAA Show AMA Supercross NFL Holiday Spectacular 4 NBC Holiday Lights Meet the Press (N) Å Conference Wall Street Holiday Lights Extra (N) Å Global Golf Adventure 5 CW Yule Log Seasonal music. (6) (TVG) In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week-Amanpour Disney Parks Christmas Day Parade (N) (TVG) NBA Basketball: Heat at Mavericks 9 KCAL Yule Log Seasonal music. (TVG) Prince Paid Program 11 FOX Hour of Power (N) (TVG) Fox News Sunday Kids News Winning Paid Program 13 MyNet Paid Program Best Buys Paid Program Best of L.A. Paid Program Uptown Girls ›› (2003) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Paid Program Hecho en Guatemala Iranian TV Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Sid Science Curios -ity Thomas Bob Builder Joy of Paint Paint This Dewberry Wyland’s Cuisine Kitchen Kitchen Sweet Life 28 KCET Cons. Wubbulous Busytown Peep Pancakes Pufnstuf Lidsville Place, Own Roadtrip Chefs Field Pépin Venetia 30 ION Turning Pnt. Discovery In Touch Mark Jeske Beyond Paid Program Inspiration Ministry Campmeeting 34 KMEX Paid Program Muchachitas Como Tu Nuestra Navidad República Deportiva en Navidad 40 KTBN Rhema Win Walk Miracle-You Redemption Love In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley From Heart King Is J. Franklin 46 KFTR Paid Tu Estilo Patrulla La Vida An P.