Emerging from the Shadows: Civil War, Human Rights, And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Plusinside Senti18 Cmufilmfest15

Pittsburgh Opera stages one of the great war horses 12 PLUSINSIDE SENTI 18 CMU FILM FEST 15 ‘BLOODLINE’ 23 WE-2 +=??B/<C(@ +,B?*(2.)??) & THURSDAY, MARCH 19, 2015 & WWW.POST-GAZETTE.COM Weekend Editor: Scott Mervis How to get listed in the Weekend Guide: Information should be sent to us two weeks prior to publication. [email protected] Send a press release, letter or flier that includes the type of event, date, address, time and phone num- Associate Editor: Karen Carlin ber of venue to: Weekend Guide, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, 34 Blvd. of the Allies, Pittsburgh 15222. Or fax THE HOT LIST [email protected] to: 412-263-1313. Sorry, we can’t take listings by phone. Email: [email protected] If you cannot send your event two weeks before publication or have late material to submit, you can post Cover design by Dan Marsula your information directly to the Post-Gazette website at http://events.post-gazette.com. » 10 Music » 14 On the Stage » 15 On Film » 18 On the Table » 23 On the Tube Jeff Mattson of Dark Star City Theatre presents the Review of “Master Review of Senti; Munch Rob Owen reviews the new Orchestra gets on board for comedy “Oblivion” by Carly Builder,”opening CMU’s film goes to Circolo. Netflix drama “Bloodline.” the annual D-Jam show. Mensch. festival; festival schedule. ALL WEEKEND SUNDAY Baroque Coffee House Big Trace Johann Sebastian Bach used to spend his Friday evenings Trace Adkins, who has done many a gig opening for Toby at Zimmermann’s Coffee House in Leipzig, Germany, where he Keith, headlines the Palace Theatre in Greensburg Sunday. -

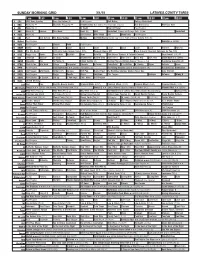

Sunday Morning Grid 12/28/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 12/28/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Chargers at Kansas City Chiefs. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News 1st Look Paid Premier League Goal Zone (N) (TVG) World/Adventure Sports 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) Outback Explore St. Jude Hospital College 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Philadelphia Eagles at New York Giants. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Black Knight ›› (2001) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Cooking Chefs Life Simply Ming Ciao Italia 28 KCET Raggs Play. Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Ed Slott’s Retirement Rescue for 2014! (TVG) Å BrainChange-Perlmutter 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) República Deportiva (TVG) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Tu Dia Tu Dia Happy Feet ››› (2006) Elijah Wood. -

Drug Prohibition and Developing Countries: Uncertain Benefi Ts, Certain Costs 9 Philip Keefer, Norman Loayza, and Rodrigo R

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized INNOCENT BYSTANDERS INNOCENT Philip Keefer and Norman Loayza, Editors andNormanLoayza, Philip Keefer Developing Countries and the War onDrugs War Countriesandthe Developing INNOCENT BYSTANDERS INNOCENT BYSTANDERS Developing Countries and the War on Drugs PHILIP KEEFER AND NORMAN LOAYZA Editors A COPUBLICATION OF PALGRAVE MACMILLAN AND THE WORLD BANK © 2010 The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street NW Washington, DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000 Internet: www.worldbank.org E-mail: [email protected] All rights reserved 1 2 3 4 13 12 11 10 A copublication of The World Bank and Palgrave Macmillan. PALGRAVE MACMILLAN Palgrave Macmillan in the United Kingdom is an imprint of Macmillan Publishers Limited, registered in England, company number 785998, of Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire, RG21 6XS. Palgrave Macmillan in the United States is a division of St. Martin’s Press LLC, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010. Palgrave Macmillan is the global academic imprint of the above companies and has companies and representatives throughout the world. Palgrave® and Macmillan® are registered trademarks in the United States, the United Kingdom, Europe, and other countries. This volume is a product of the staff of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank. The fi ndings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this volume do not nec- essarily refl ect World Bank policy or the views of the Executive Directors of The World Bank or the governments they represent. The publication of this volume should not be construed as an endorse- ment by The World Bank of any arguments, either for or against, the legalization of drugs. -

The Pacific Coast and the Casual Labor Economy, 1919-1933

© Copyright 2015 Alexander James Morrow i Laboring for the Day: The Pacific Coast and the Casual Labor Economy, 1919-1933 Alexander James Morrow A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2015 Reading Committee: James N. Gregory, Chair Moon-Ho Jung Ileana Rodriguez Silva Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Department of History ii University of Washington Abstract Laboring for the Day: The Pacific Coast and the Casual Labor Economy, 1919-1933 Alexander James Morrow Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor James Gregory Department of History This dissertation explores the economic and cultural (re)definition of labor and laborers. It traces the growing reliance upon contingent work as the foundation for industrial capitalism along the Pacific Coast; the shaping of urban space according to the demands of workers and capital; the formation of a working class subject through the discourse and social practices of both laborers and intellectuals; and workers’ struggles to improve their circumstances in the face of coercive and onerous conditions. Woven together, these strands reveal the consequences of a regional economy built upon contingent and migratory forms of labor. This workforce was hardly new to the American West, but the Pacific Coast’s reliance upon contingent labor reached its apogee after World War I, drawing hundreds of thousands of young men through far flung circuits of migration that stretched across the Pacific and into Latin America, transforming its largest urban centers and working class demography in the process. The presence of this substantial workforce (itinerant, unattached, and racially heterogeneous) was out step with the expectations of the modern American worker (stable, married, and white), and became the warrant for social investigators, employers, the state, and other workers to sharpen the lines of solidarity and exclusion. -

Sunday Morning Grid 3/1/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 3/1/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Bull Riding College Basketball 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å Snowboarding U.S. Grand Prix: Slopestyle. (Taped) Red Bull Series PGA Tour Golf 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Explore This Week News (N) NBA Basketball Clippers at Chicago Bulls. (N) Å Basketball 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday NASCAR Racing Sprint Cup Series: Folds of Honor QuikTrip 500. (N) 13 MyNet Paid Program Swimfan › (2002) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR T’ai Chi, Health JJ Virgin’s Sugar Impact Secret (TVG) Deepak Chopra MD Suze Orman’s Financial Solutions for You (TVG) 28 KCET Raggs New. Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Rick Steves’ Europe: A Cultural Carnival Over Hawai’i (TVG) Å 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY7) Doki (TVY7) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly Uncle Buck ›› (1989) 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Al Punto (N) Fútbol Central (N) Mexico Primera Division Soccer: Toluca vs Azul República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. -

NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC Program Schedule June(Weekly) MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT SUN 4.11.18.25 5.12.19.26 6.13.20.27 7.14.21.28 1.8.15.22.29 2.9.16.23.30 3.10.17.24

NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC Program Schedule June(weekly) MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT SUN 4.11.18.25 5.12.19.26 6.13.20.27 7.14.21.28 1.8.15.22.29 2.9.16.23.30 3.10.17.24 400 400 Hitler's Last Year、 Family Guns、 Family Guns、 WW2 Hell Under the Sea、 Underworld, Inc. Nazi Attack On America、 Nazi World War Weird Apocalypse World War I、 Apocalypse: The Second World My Fighting Season One Strange Rock Long Road Home America's Great War 1917-1918 War 430 430 500 500 Time Scanners、Return From The Dead、Into The Crystal Cave、Viking Apocalypse、 Borneo's Secret Kingdom Chain of Command Hitler's Jurassic Monsters、Secrets of Christ's Tomb: Explorer Special、Invaders、 →Wild Namibia →I Wouldn't Go In There Mystery of The Disappearing Skyjacker、Paranatural II、Secret History of UFO's、Roswell UFO Secrets、Invasion Earth →Wild Botswana: Lion Brotherhood 530 530 600 information 600 630 Brain Games 4、Is It Real?、Mad Scientists 630 700 700 Return of The Lion、Game Of Lions、Caught in the Act V、 Planet Carnivore、Blood Rivals: Lion vs. Buffalo、Brutal Killers、 Dr. K's Exotic Animal ER Cat Wars: Lion vs. Cheetah、Lion vs. Giraffe、Superpride、Blood Rivals: Hippo V. Lion、 Supercar Megabuild2 Car S.O.S.Ⅱ Season 3 Attack of The Big Cats、Big Cat Games、The Jungle King Compilation →Shido Nakamura's unexpected trip by Golf GTI Dynamic →CAR S.O.S.Ⅳ Test broadcasting Program(22nd) 730 730 800 800 Two Tales of China、 CAR S.O.S.Ⅲ Big, Bigger, Biggest 2、Nazi World War Weird、Das Reich - Hitler's Death Squad、Chasing UFOs China From Above、 Megafactories →Shido Nakamura's unexpected trip by Golf GTI Dynamic Maritime China 830 830 900 information 900 930 930 Cosmos: A Spacetime Odyssey、Moon Landings Declassified、Roswell UFO Secrets、 Survive the Wild Wicked Tuna 7 Genius(18h ~11:00) 1000 1000 1030 information 1030 Pope vs. -

Idealized Alaskan Themes Through Media and Their Influence on Culture, Tourism, and Policy

'I am the last frontier': idealized Alaskan themes through media and their influence on culture, tourism, and policy Item Type Other Authors Lawhorne, Rebecca Download date 04/10/2021 09:20:08 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/11122/11871 ‘I AM THE LAST FRONTIER’: IDEALIZED ALASKAN THEMES THROUGH MEDIA AND THEIR INFLUENCE ON CULTURE, TOURISM, AND POLICY Rebecca Lawhorne, B.A. A Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degreed of Master of Arts In Professional Communication University of Alaska Fairbanks May 2020 APPROVED: Rich Hum, Committee Chair Brian O’Donoghue, Committee Member Tori McDermott, Committee Member Charles Mason, Department Chair Department of Communication and Journalism Abstract A large body of literature suggests that in media history there exists prominent narrative themes about the State of Alaska. These themes affect both resident and visitor perceptions and judgements about what life is and should be in Alaska and subsequently, create values that ultimately influence how the state operates. The evolution of these themes are understood in a modern capacity in the Alaska reality television phenomenon of the early 2000’s. This study concludes that the effect of these forms of media may create conflict and ultimately, may not work in the state’s best interests. The researcher believes that the state has new tools to use in its image management. She recommends that new forms of media be cultivated Alaskan residents, tourism industry leaders and special interest groups as a means of alleviating the misrepresentations, expanding communication representation and developing positive visitor experiences for younger visitors who utilize new forms of media. -

P32 Layout 1

WEDNESDAY, MAY 24, 2017 TV PROGRAMS 04:15 Lip Sync Battle 01:15 Sabrina Secrets Of A Teenage 23:20 Henry Hugglemonster 14:05 Second Wives Club 04:40 Ridiculousness Witch 23:35 The Hive 15:00 E! News 05:05 Disaster Date 01:40 Hank Zipzer 23:45 Loopdidoo 15:15 E! News: Daily Pop 05:30 Sweat Inc. 02:05 Binny And The Ghost 16:10 Keeping Up With The Kardashians 06:20 Life Or Debt 02:30 Binny And The Ghost 17:05 Live From The Red Carpet 00:15 Survivor 07:10 Disorderly Conduct: Video On 02:55 Hank Zipzer 19:00 E! News 02:00 Sharknado 2: The Second One Patrol 03:15 The Hive 20:00 Fashion Police 03:30 Fast & Furious 7 08:05 Disaster Date 03:20 Sabrina Secrets Of A Teenage 21:00 Botched 06:00 Mission: Impossible - Rogue 08:30 Disaster Date Witch 22:00 Botched Nation 08:55 Ridiculousness 03:45 Sabrina Secrets Of A Teenage 23:00 E! News 08:15 Bad Company 09:20 Workaholics Witch 00:20 Street Outlaws 23:15 Hollywood Medium With Tyler 10:15 Licence To Kill 09:45 Disaster Date 04:10 Hank Zipzer 01:10 Todd Sampson's Body Hack Henry 12:30 Fast & Furious 7 10:10 Ridiculousness 04:35 Binny And The Ghost 02:00 Marooned With Ed Stafford 15:00 Mission: Impossible - Rogue 10:35 Impractical Jokers 05:00 Binny And The Ghost 02:50 Still Alive Nation 11:00 Hungry Investors 05:25 Hank Zipzer 03:40 Diesel Brothers 17:15 Run All Night 11:50 The Jim Gaffigan Show 05:45 The Hive 04:30 Storage Hunters UK 19:15 Golden Eye 12:15 Lip Sync Battle 05:50 The 7D 05:00 How Do They Do It? 21:30 San Andreas 12:40 Impractical Jokers 06:00 Jessie 05:30 How Do They Do It? 00:00 Diners, -

Sunday Morning Grid 12/25/11

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 12/25/11 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning (N) Å Face/Nation A Gospel Christmas NCAA Show AMA Supercross NFL Holiday Spectacular 4 NBC Holiday Lights Meet the Press (N) Å Conference Wall Street Holiday Lights Extra (N) Å Global Golf Adventure 5 CW Yule Log Seasonal music. (6) (TVG) In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week-Amanpour Disney Parks Christmas Day Parade (N) (TVG) NBA Basketball: Heat at Mavericks 9 KCAL Yule Log Seasonal music. (TVG) Prince Paid Program 11 FOX Hour of Power (N) (TVG) Fox News Sunday Kids News Winning Paid Program 13 MyNet Paid Program Best Buys Paid Program Best of L.A. Paid Program Uptown Girls ›› (2003) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Paid Program Hecho en Guatemala Iranian TV Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Sid Science Curios -ity Thomas Bob Builder Joy of Paint Paint This Dewberry Wyland’s Cuisine Kitchen Kitchen Sweet Life 28 KCET Cons. Wubbulous Busytown Peep Pancakes Pufnstuf Lidsville Place, Own Roadtrip Chefs Field Pépin Venetia 30 ION Turning Pnt. Discovery In Touch Mark Jeske Beyond Paid Program Inspiration Ministry Campmeeting 34 KMEX Paid Program Muchachitas Como Tu Nuestra Navidad República Deportiva en Navidad 40 KTBN Rhema Win Walk Miracle-You Redemption Love In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley From Heart King Is J. Franklin 46 KFTR Paid Tu Estilo Patrulla La Vida An P. -

Port Back on Comp Plan

Fifteen and done: Giants devastate Packers in Green Bay /B1 MONDAY CITRUS COUNTY TODAY & Tuesday morning HIGH Partly cloudy, winds 5 to 73 10 mph. Slight chance LOW of rain Tuesday. 47 PAGE A4 www.chronicleonline.com JANUARY 16, 2012 Florida’s Best Community Newspaper Serving Florida’s Best Community 50¢ VOLUME 117 ISSUE 162 NEWS BRIEFS Port back on comp plan Government center to open CHRIS VAN ORMER As part of the groundwork Commissioners (BOCC) portation planner, ex- “One of the recommenda- Tuesday Staff Writer to conduct a feasibility conducted a transmittal plained the background for tions of the 1996 evaluation study for the proposed Port public hearing on the port the need to put back the appraisal report was to re- The new West Citrus Keeping the port project Citrus project, county staff element and voted unani- port element. Jones said the move the port element from Government Center in on course, commissioners on had to put the port element mously to authorize trans- original comprehensive the comprehensive plan,” Meadowcrest opens for Tuesday agreed to add an- back into the comprehen- mittal of the element to plan adopted in 1989 in- Jones said. “The board in business Tuesday other chapter to the county’s sive plan. The Citrus state agencies for review. cluded a ports and aviation morning. comprehensive plan. County Board of County Cynthia Jones, trans- element. See PORT/Page A4 The satellite offices for clerk of court, tax collec- tor, property appraiser and supervisor of elec- tions relocated from their old offices in a Crystal River shopping center on U.S. -

Before the FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION Washington, D.C

Before the FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Application of Affiliated Media, Inc. ) File No. BALCDT-20130125ABD FCC Trust, Assignor, and Denali Media ) Facility ID No. 49632 Anchorage, Corp., Assignee, For Consent ) to Assign the License of Station ) KTVA (TV), Anchorage, Alaska ) ) Application of Dan Etulain, Assignor, and ) File Nos. BALDTL-20130125AAL Denali Media Southeast, Corp., Assignee, ) & BALTVL-20130125AAK For Consent to Assign the Licenses of ) Facility ID Nos. 188833 & 15348 Stations KATH-LD, Juneau-Douglas, ) Alaska and KSCT-LP, Sitka, Alaska ) To: The Media Bureau OPPOSITION OF DENALI MEDIA ANCHORAGE, CORP., AND DENALI MEDIA SOUTHEAST, CORP., TO PETITION TO DENY Kurt Wimmer Eve R. Pogoriler Daniel H. Kahn COVINGTON & BURLING LLP 1201 Pennsylvania Avenue NW Washington, D.C. 20004-2401 (202) 662-6000 Counsel for Denali Media Anchorage, Corp., and Denali Media Southeast, Corp. March 14, 2013 SUMMARY General Communication, Inc., here proposes to acquire one television station in Anchorage (KTVA) and two low-power stations in Juneau (KATH) and Sitka (KSCT) with the goal of attracting viewers with first-rate local programming. This small transaction will create large benefits for Alaska, which suffers from a stunning lack of broadcast competition, local news diversity, and technological innovation. GCI will invest heavily in local programming, more than doubling KTVA’s news offerings, hiring dozens of full-time news employees, and launching Alaska’s first high-definition local news. GCI has a 30-year history of bringing the benefits of competition to Alaska, investing more than $1 billion in the state to expand a variety of communications services, and forcing incumbents to improve their own services along the way. -

Bilbreyh2017.Pdf

The Crown of Madness Prologue Standing silent, the large crowd stared toward the castle door. Each held a red thorny rose, gripping it tightly and drawing blood. They stood there for nearly an hour—no one said a word and no one faltered. At last, the giant entryway opened. A procession of darkly dressed soldiers filed out in a close, uniform line, followed by the king, dressed in all white except for the dark iron crown on his head. Their leader looked tired but proud, defeated yet strong. Each step the king took was methodical. His face unchanging, he stared forward toward the platform in the center of the crowd. The tired man stopped at the edge of the path created through the audience. All but two of the knights continued on to the platform. They knelt down toward the king upon arrival at their destination. A deep, mournful horn sounded from one of the castle towers. It bellowed seven times. Roses were passed and thrown into the opening made for the king. The ground became completely obscured by the bloody flowers and the king began walking. Again, he walked slowly and deliberately, showing only strength though in great anguish. Finally, he arrived at the platform and climbed the short flight of stairs. One knight knelt at the top of the stairs, facing away from the king, and those around the platform stood to turn toward him. One by one, the warriors knelt, shortly followed by the crowd around them. All were on their knees except the king and his appointed executioner.