Before the FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION Washington, D.C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Alaska Story

COMPASS BEARINGS Gary Walter The Alaska Story his is the season for regional annual meet- our own fledgling movement, just four years old at ings. The Covenant, though one church, has the time, to step into the initiative in their place. The Televen regions within the United States and Covenant did, and Alaska became one of our very first Canada known as conferences. Each year delegates mission endeavors, along with China. The blight of a from churches within those areas gather to celebrate few early missionaries being sidetracked by the gold what God is doing and to deliberate on where God is rush notwithstanding, the emerging endeavor, joining leading. It is also a time to make new friendships and the efforts of Alaska Native leaders and missionaries, deepen old bonds. went on to develop churches, orphanages, schools, This year I traveled to the meeting of our Alaska and clinics over the first several decades. region, known as ECCAK (Evangelical Covenant Alaska is where the Covenant Church first grew Church of Alaska). Given the scope of what we do in multiethnic understanding. It hasn’t always been and the relatively small population of the state, Alaska easy, and it hasn’t always been done right. No one may be the only place in the United States and Cana- would deny that there have been hurtful, paternalistic, da where having heard of the Covenant is culturally and insensitive moments. But just because we haven’t normative—well, OK, at least not all that unusual. always gotten it right, doesn’t mean it isn’t right. -

A 040909 Breeze Thursday

Post Comments, share Views, read Blogs on CaPe-Coral-daily-Breeze.Com Inside today’s SER VING CAPE C ORA L, PINE ISLAND & N. FT. MYERS Breeze APE ORAL RR eal C C l E s MARKETER state Your complete Cape Coral, Lee County 5 Be edroo Acce om Sa real estate guide ess Ho ailboa N om at OR m t TH E e DI e TI ! AP ON ! RI ! L 23, 2 2009 COVER AILY REEZE PRESENTED B D B See Page Y WONDERLAND REA 9 LTY WEATHER: Partly Sunny • Tonight: Clear • Saturday: Partly Sunny — 2A cape-coral-daily-breeze.com Vol. 48, No. 95 Friday, April 24, 2009 50 cents Home prices down, sales up in metro area for March Florida association releases its report “The buyers are going after the foreclosures.” — Paula Hellenbrand, president of the By GRAY ROHRER area fell to $88,500, the lowest of Foreclosures are again the main Cape Coral Association of Realtors [email protected] all the 20 Florida metro areas con- culprit for decreased home prices, A report released Thursday by tained in the report. The number but they are also the reason home the Florida Association of Realtors reflects a 9 percent decrease from sales are increasing. California-based company that gath- Hellenbrand said the sales activi- told a familiar story for the local February and a 58 percent drop “The buyers are going after the ers foreclosure data, the Cape Coral- ty is greater in Cape Coral than in housing market — home prices are from March 2008. foreclosures,” said Paula Fort Myers metro area had the Fort Myers because there was a down, but sales are up, way up. -

Friday Prime Time, April 17 4 P.M

April 17 - 23, 2009 SPANISH FORK CABLE GUIDE 9 Friday Prime Time, April 17 4 P.M. 4:30 5 P.M. 5:30 6 P.M. 6:30 7 P.M. 7:30 8 P.M. 8:30 9 P.M. 9:30 10 P.M. 10:30 11 P.M. 11:30 BASIC CABLE Oprah Winfrey Å 4 News (N) Å CBS Evening News (N) Å Entertainment Ghost Whisperer “Save Our Flashpoint “First in Line” ’ NUMB3RS “Jack of All Trades” News (N) Å (10:35) Late Show With David Late Late Show KUTV 2 News-Couric Tonight Souls” ’ Å 4 Å 4 ’ Å 4 Letterman (N) ’ 4 KJZZ 3The People’s Court (N) 4 The Insider 4 Frasier ’ 4 Friends ’ 4 Friends 5 Fortune Jeopardy! 3 Dr. Phil ’ Å 4 News (N) Å Scrubs ’ 5 Scrubs ’ 5 Entertain The Insider 4 The Ellen DeGeneres Show (N) News (N) World News- News (N) Two and a Half Wife Swap “Burroughs/Padovan- Supernanny “DeMello Family” 20/20 ’ Å 4 News (N) (10:35) Night- Access Holly- (11:36) Extra KTVX 4’ Å 3 Gibson Men 5 Hickman” (N) ’ 4 (N) ’ Å line (N) 3 wood (N) 4 (N) Å 4 News (N) Å News (N) Å News (N) Å NBC Nightly News (N) Å News (N) Å Howie Do It Howie Do It Dateline NBC A police of cer looks into the disappearance of a News (N) Å (10:35) The Tonight Show With Late Night- KSL 5 News (N) 3 (N) ’ Å (N) ’ Å Michigan woman. (N) ’ Å Jay Leno ’ Å 5 Jimmy Fallon TBS 6Raymond Friends ’ 5 Seinfeld ’ 4 Seinfeld ’ 4 Family Guy 5 Family Guy 5 ‘Happy Gilmore’ (PG-13, ’96) ›› Adam Sandler. -

Thursday Morning, March 10

THURSDAY MORNING, MARCH 10 FRO 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 COM 4:30 KATU News This Morning (N) Good Morning America (N) (cc) AM Northwest Who Wants to Be The View Actress Michelle Rodri- Live With Regis and Kelly Talent 2/KATU 2 2 (cc) (Cont’d) (cc) a Millionaire guez. (N) (cc) (TV14) judge Jennifer Lopez. (N) (TVPG) KOIN Local 6 Early at 6 (N) (cc) The Early Show (N) (cc) Let’s Make a Deal (N) (cc) (TVPG) The Price Is Right (N) (cc) (TVG) The Young and the Restless (N) (cc) 6/KOIN 6 6 (TV14) Newschannel 8 at Sunrise at 6:00 Today Aaron Eckhart; Avril Lavigne performs. (N) (cc) The Nate Berkus Show Do-it-your- 8/KGW 8 8 AM (N) (cc) self projects. (cc) (TVPG) Sit and Be Fit Between the Curious George Cat in the Hat Super Why! (cc) Dinosaur Train Sesame Street Search for the Sid the Science Clifford the Big Martha Speaks WordWorld (TVY) 10/KOPB 10 10 (cc) (TVG) Lions (TVY) (TVY) Knows a Lot (TVY) (TVY) Blue Bar Pigeon. (TVY) Kid (TVY) Red Dog (TVY) (TVY) Good Day Oregon-6 (N) Good Day Oregon (N) Better (cc) (TVPG) The 700 Club (cc) (TVPG) 12/KPTV 12 12 Portland Public Affairs Paid Paid The Magic School Willa’s Wild Life Through the Bible Zola Levitt Pres- Paid Paid Paid 22/KPXG 5 5 Bus (TVY7) ents (TVG) Changing Your John Hagee Rod Parsley (cc) This Is Your Day Kenneth Cope- Unfolding Majesty Life Change Cafe John Bishop TV Changing Your John Hagee Rod Parsley (cc) This Is Your Day 24/KNMT 20 20 World (TVG) Today (cc) (TVG) (TVG) (cc) (TVG) land (TVG) (cc) World (TVG) Today (cc) (TVG) (TVG) (cc) (TVG) George Lopez George Lopez The Young Icons Just Shoot Me My Name Is Earl My Name Is Earl Maury (cc) (TV14) Swift Justice- Swift Justice- The Steve Wilkos Show Abuse of a 32/KRCW 3 3 (cc) (TVPG) (cc) (TVPG) (TVG) (cc) (TVPG) (TV14) (TV14) Nancy Grace Nancy Grace young boy. -

March 26 to April 8, 2013 Discovery Channel Primetime Spotlight

March 26 TO April 8, 2013 Discovery Channel Primetime Spotlight Contact: Marilyn Montgomery, 310-975-1630, [email protected] Photos, Videos & Additional Information: http://press.discovery.com SPOTLIGHT: UPCOMING PREMIERES/FINALES/SPECIALS HOW WE INVENTED THE WORLD 4-part special premieres on Tuesday, March 26 at 9PM ET/PT followed by a new episode at 10PM ET/PT How We Invented the World examines four inventions that define the modern world – cell phones, cars, planes, and skyscrapers. Each episode in this 4-part series reveals the fascinating stories and seemingly random events that ultimately led to the creation of these iconic inventions. By showcasing the minds behind the innovations that have shaped our lives in unimaginable and unanticipated ways, this series highlights stories of human ingenuity, extraordinary connections, unprecedented experimentation, and jaw-dropping events that have shaped the world as we know it. Press Contact: Emily Robinson, [email protected], 212-548-5103 Press Web: http://press.discovery.com/us/dsc/programs/how-we-invented-world/ WEED COUNTRY season finale airs on Wednesday, March 27 at 10PM ET/PT Harvest Hell: The Jackson County and Siskiyou County Sheriff’s Departments are teaming up to take down the biggest grow of the season. Mere miles away Shotwell arrives at Mike Boutin’s house to pick up the weed he feels will put him back on top, but Mike isn’t ready to hand over any weed, having not spoken to Matt since their first meeting. Late at night, Mike’s plants are ripped from the ground and Mike suspects it was his guests who did it. -

The Pacific Coast and the Casual Labor Economy, 1919-1933

© Copyright 2015 Alexander James Morrow i Laboring for the Day: The Pacific Coast and the Casual Labor Economy, 1919-1933 Alexander James Morrow A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2015 Reading Committee: James N. Gregory, Chair Moon-Ho Jung Ileana Rodriguez Silva Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Department of History ii University of Washington Abstract Laboring for the Day: The Pacific Coast and the Casual Labor Economy, 1919-1933 Alexander James Morrow Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor James Gregory Department of History This dissertation explores the economic and cultural (re)definition of labor and laborers. It traces the growing reliance upon contingent work as the foundation for industrial capitalism along the Pacific Coast; the shaping of urban space according to the demands of workers and capital; the formation of a working class subject through the discourse and social practices of both laborers and intellectuals; and workers’ struggles to improve their circumstances in the face of coercive and onerous conditions. Woven together, these strands reveal the consequences of a regional economy built upon contingent and migratory forms of labor. This workforce was hardly new to the American West, but the Pacific Coast’s reliance upon contingent labor reached its apogee after World War I, drawing hundreds of thousands of young men through far flung circuits of migration that stretched across the Pacific and into Latin America, transforming its largest urban centers and working class demography in the process. The presence of this substantial workforce (itinerant, unattached, and racially heterogeneous) was out step with the expectations of the modern American worker (stable, married, and white), and became the warrant for social investigators, employers, the state, and other workers to sharpen the lines of solidarity and exclusion. -

Country Carpet

PAGE SIX-BFOUR-B TTHURSDAYHURSDAY, ,F AEBRUARYUGUST 23, 2, 20122012 THE LICKING VALLEYALLEY COURIER Stop By Speedy Your Feed Frederick & May Elam’sElam’s FurnitureFurnitureCash SpecialistsYour Feed For All YourStop Refrigeration By New & Used Furniture & AppliancesCheck Specialists NeedsFrederick With A Line& May Of QUALITY FrigidaireFor All Your 2 Miles West Of West Liberty - Phone 743-4196 Safely and Comfortably Heat 500, 1000, to 1500 sq. Feet For Pennies Per Day! 22.6 Cubic Feet Advance QUALITYFEED RefrigerationAppliances. Needs With A iHeater PTC Infrared Heating Systems!!! $ 00 •Portable 110V FEED Line Of Frigidaire Appliances. We hold all customer Regular FOR ALL Remember We 999 •Superior Design and Quality • All Popular Brands • Custom Feed Blends Need Cash? Checks for 30 days! Price •Full Function Credit Card Sized FORYOUR ALL ServiceRemember What We We Service Sell! 22.6 Cubic Feet Remote Control •• All Animal Popular Health Brands Products • Custom Feed Blends •Available in Cherry & Black Finish YOURFARM $ 00 $379 •• Animal Pet Food Health & Supplies Products •Horse Tack What We Sell! Speedy Cash •Reduces Energy Usage by 30-50% 999 Sale •Heats Multiple Rooms •• Pet Farm Food & Garden & Supplies Supplies •Horse Tack ANIMALSFARM Price •1 Year Factory Warranty •• FarmPlus Ole & GardenYeller Dog Supplies Food Frederick & May Brentny Cantrell •Thermostst Controlled ANIMALS $319 •Cannot Start Fires • Plus Ole Yeller Dog Food Frederick & May 1209 West Main St. No Glass Bulbs •Child and Pet Safe! Lyon Feed of West Liberty Lumber Co., Inc. West Liberty, KY 41472 ALLAN’S TIRE SUPPLY, INC. Lyon(Moved Feed To New Location of West Behind Save•A•Lot)Liberty 919 PRESTONSBURG ST. -

Put Your Foot Down

PAGE SIX-B THURSDAY, MARCH 1, 2012 THE LICKING VALLEY COURIER Elam’sElam’s FurnitureFurniture Your Feed Stop By New & Used Furniture & Appliances Specialists Frederick & May For All Your 2 Miles West Of West Liberty - Phone 743-4196 Safely and Comfortably Heat 500, 1000, to 1500 sq. Feet For Pennies Per Day! iHeater PTC Infrared Heating Systems!!! QUALITY Refrigeration Needs With A •Portable 110V FEED Line Of Frigidaire Appliances. Regular •Superior Design and Quality Price •Full Function Credit Card Sized FOR ALL Remember We Service 22.6 Cubic Feet Remote Control • All Popular Brands • Custom Feed Blends •Available in Cherry & Black Finish YOUR $ 00 $379 • Animal Health Products What We Sell! •Reduces Energy Usage by 30-50% 999 Sale •Heats Multiple Rooms • Pet Food & Supplies •Horse Tack FARM Price •1 Year Factory Warranty • Farm & Garden Supplies •Thermostst Controlled ANIMALS $319 •Cannot Start Fires • Plus Ole Yeller Dog Food Frederick & May No Glass Bulbs •Child and Pet Safe! Lyon Feed of West Liberty FINANCING AVAILABLE! (Moved To New Location Behind Save•A•Lot) Lumber Co., Inc. Williams Furniture 919 PRESTONSBURG ST. • WEST LIBERTY We Now Have A Good Selection 548 Prestonsburg St. • West Liberty, Ky. 7598 Liberty Road • West Liberty, Ky. TPAGEHE LICKING TWE LVVAELLEY COURIER THURSDAYTHURSDAY, NO, VJEMBERUNE 14, 24, 2012 2011 THE LICKING VALLEY COURIER Of Used Furniture Phone (606) 743-3405 Phone: (606) 743-2140 Call 743-3136 PAGEor 743-3162 SEVEN-B Holliday’s Stop By Your Feed Frederick & May OutdoorElam’sElam’s Power FurnitureFurniture Equipment SpecialistsYour Feed For All YourStop Refrigeration By New4191 & Hwy.Used 1000 Furniture • West & Liberty, Appliances Ky. -

A Flatlander's View of Flying Alaska

SAY AGAIN? THE FINANCE AND TAXES OF ATC MISCONCEPTIONS FLYING YOUR ECLIPSE FOR BUSINESS EJOPA EDITION THE PRIVATE JET SUMMER 2017 MAGAZINE A FLATLANDER’S VIEW OF FLYING ALASKA WHY GET MISSION ALL ABOUT UPSET? ACCOMPLISHED OSHKOSH UPSET TRAINING CIRRUS GETS EVEN BETTER EAA AIR VENTURE Contrails.EJOPA.indd 1 8/14/17 1:51 PM THIS IS EPIC. AIRCRAFT SALES & ACQUISITIONS MAXIMUM TIME TO CLIMB RANGE MAX RANGE ECO PAYLOAD AEROCOR has quickly become the world's number one VLJ broker, with more listings and CRUISE SL TO 34,000 CRUISE CRUISE (FULL FUEL) more completed transactions than the competition. Our success is driven by product 325 KTAS 15 Minutes 1385 NM 1650 NM 1120 lbs. specialization and direct access to the largest pool of light turbine buyers. Find out why buyers and sellers are switching to AEROCOR. ACCURATE INTEGRITY UNPARALLELED PRICING EXPOSURE Proprietary market Honest & fair Strategic partnership tracking & representation with Aerista, the world's valuation tools largest Cirrus dealer CALL US TODAY! (747)(747) 777-9505 777-9505 or [email protected] or [email protected] www.epicaircraft.com 541-639-4602 888-FLY-EPIC WWW .AEROCOR.COM Contrails.EJOPA.indd 2-3 8/14/17 1:51 PM THIS IS EPIC. AIRCRAFT SALES & ACQUISITIONS MAXIMUM TIME TO CLIMB RANGE MAX RANGE ECO PAYLOAD AEROCOR has quickly become the world's number one VLJ broker, with more listings and CRUISE SL TO 34,000 CRUISE CRUISE (FULL FUEL) more completed transactions than the competition. Our success is driven by product 325 KTAS 15 Minutes 1385 NM 1650 NM 1120 lbs. -

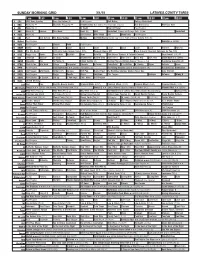

Sunday Morning Grid 3/1/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 3/1/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Bull Riding College Basketball 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å Snowboarding U.S. Grand Prix: Slopestyle. (Taped) Red Bull Series PGA Tour Golf 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Explore This Week News (N) NBA Basketball Clippers at Chicago Bulls. (N) Å Basketball 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday NASCAR Racing Sprint Cup Series: Folds of Honor QuikTrip 500. (N) 13 MyNet Paid Program Swimfan › (2002) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR T’ai Chi, Health JJ Virgin’s Sugar Impact Secret (TVG) Deepak Chopra MD Suze Orman’s Financial Solutions for You (TVG) 28 KCET Raggs New. Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Rick Steves’ Europe: A Cultural Carnival Over Hawai’i (TVG) Å 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY7) Doki (TVY7) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly Uncle Buck ›› (1989) 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Al Punto (N) Fútbol Central (N) Mexico Primera Division Soccer: Toluca vs Azul República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. -

Idealized Alaskan Themes Through Media and Their Influence on Culture, Tourism, and Policy

'I am the last frontier': idealized Alaskan themes through media and their influence on culture, tourism, and policy Item Type Other Authors Lawhorne, Rebecca Download date 04/10/2021 09:20:08 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/11122/11871 ‘I AM THE LAST FRONTIER’: IDEALIZED ALASKAN THEMES THROUGH MEDIA AND THEIR INFLUENCE ON CULTURE, TOURISM, AND POLICY Rebecca Lawhorne, B.A. A Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degreed of Master of Arts In Professional Communication University of Alaska Fairbanks May 2020 APPROVED: Rich Hum, Committee Chair Brian O’Donoghue, Committee Member Tori McDermott, Committee Member Charles Mason, Department Chair Department of Communication and Journalism Abstract A large body of literature suggests that in media history there exists prominent narrative themes about the State of Alaska. These themes affect both resident and visitor perceptions and judgements about what life is and should be in Alaska and subsequently, create values that ultimately influence how the state operates. The evolution of these themes are understood in a modern capacity in the Alaska reality television phenomenon of the early 2000’s. This study concludes that the effect of these forms of media may create conflict and ultimately, may not work in the state’s best interests. The researcher believes that the state has new tools to use in its image management. She recommends that new forms of media be cultivated Alaskan residents, tourism industry leaders and special interest groups as a means of alleviating the misrepresentations, expanding communication representation and developing positive visitor experiences for younger visitors who utilize new forms of media. -

Port Back on Comp Plan

Fifteen and done: Giants devastate Packers in Green Bay /B1 MONDAY CITRUS COUNTY TODAY & Tuesday morning HIGH Partly cloudy, winds 5 to 73 10 mph. Slight chance LOW of rain Tuesday. 47 PAGE A4 www.chronicleonline.com JANUARY 16, 2012 Florida’s Best Community Newspaper Serving Florida’s Best Community 50¢ VOLUME 117 ISSUE 162 NEWS BRIEFS Port back on comp plan Government center to open CHRIS VAN ORMER As part of the groundwork Commissioners (BOCC) portation planner, ex- “One of the recommenda- Tuesday Staff Writer to conduct a feasibility conducted a transmittal plained the background for tions of the 1996 evaluation study for the proposed Port public hearing on the port the need to put back the appraisal report was to re- The new West Citrus Keeping the port project Citrus project, county staff element and voted unani- port element. Jones said the move the port element from Government Center in on course, commissioners on had to put the port element mously to authorize trans- original comprehensive the comprehensive plan,” Meadowcrest opens for Tuesday agreed to add an- back into the comprehen- mittal of the element to plan adopted in 1989 in- Jones said. “The board in business Tuesday other chapter to the county’s sive plan. The Citrus state agencies for review. cluded a ports and aviation morning. comprehensive plan. County Board of County Cynthia Jones, trans- element. See PORT/Page A4 The satellite offices for clerk of court, tax collec- tor, property appraiser and supervisor of elec- tions relocated from their old offices in a Crystal River shopping center on U.S.