Idealized Alaskan Themes Through Media and Their Influence on Culture, Tourism, and Policy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Plusinside Senti18 Cmufilmfest15

Pittsburgh Opera stages one of the great war horses 12 PLUSINSIDE SENTI 18 CMU FILM FEST 15 ‘BLOODLINE’ 23 WE-2 +=??B/<C(@ +,B?*(2.)??) & THURSDAY, MARCH 19, 2015 & WWW.POST-GAZETTE.COM Weekend Editor: Scott Mervis How to get listed in the Weekend Guide: Information should be sent to us two weeks prior to publication. [email protected] Send a press release, letter or flier that includes the type of event, date, address, time and phone num- Associate Editor: Karen Carlin ber of venue to: Weekend Guide, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, 34 Blvd. of the Allies, Pittsburgh 15222. Or fax THE HOT LIST [email protected] to: 412-263-1313. Sorry, we can’t take listings by phone. Email: [email protected] If you cannot send your event two weeks before publication or have late material to submit, you can post Cover design by Dan Marsula your information directly to the Post-Gazette website at http://events.post-gazette.com. » 10 Music » 14 On the Stage » 15 On Film » 18 On the Table » 23 On the Tube Jeff Mattson of Dark Star City Theatre presents the Review of “Master Review of Senti; Munch Rob Owen reviews the new Orchestra gets on board for comedy “Oblivion” by Carly Builder,”opening CMU’s film goes to Circolo. Netflix drama “Bloodline.” the annual D-Jam show. Mensch. festival; festival schedule. ALL WEEKEND SUNDAY Baroque Coffee House Big Trace Johann Sebastian Bach used to spend his Friday evenings Trace Adkins, who has done many a gig opening for Toby at Zimmermann’s Coffee House in Leipzig, Germany, where he Keith, headlines the Palace Theatre in Greensburg Sunday. -

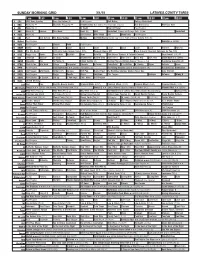

Sunday Morning Grid 12/28/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 12/28/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Chargers at Kansas City Chiefs. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News 1st Look Paid Premier League Goal Zone (N) (TVG) World/Adventure Sports 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) Outback Explore St. Jude Hospital College 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Philadelphia Eagles at New York Giants. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Black Knight ›› (2001) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Cooking Chefs Life Simply Ming Ciao Italia 28 KCET Raggs Play. Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Ed Slott’s Retirement Rescue for 2014! (TVG) Å BrainChange-Perlmutter 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) República Deportiva (TVG) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Tu Dia Tu Dia Happy Feet ››› (2006) Elijah Wood. -

Cablefax Program Awards 2021 Winners and Nominees

March 31, 2021 SPECIAL ISSUE CFX Program Awards Honoring the 2021 Nominees & Winners PROGRAM AWARDS March 31, 2021 The Cablefax Program Awards has a long tradition of honoring the best programming in a particular content niche, regardless of where the content originated or how consumers watch it. We’ve recognized breakout shows, such as “Schitt’s Creek,” “Mad Men” and “RuPaul’s Drag Race,” long before those other award programs caught up. In this special issue, we reveal our picks for best programming in 2020 and introduce some special categories related to the pandemic. Read all about it! As an interactive bonus, the photos with red borders have embedded links, so click on the winner photos to sample the program. — Amy Maclean, Editorial Director Best Overall Content by Genre Comedy African American Winner: The Conners — ABC Entertainment Winner: Walk Against Fear: James Meredith — Smithsonian Channel This timely documentary is named after James Meredith’s 1966 Walk Against Fear, in which he set out to show a Black man could walk peace- fully in Mississippi. He was shot on the second day. What really sets this The Conners shines at finding ways to make you laugh through life’s film apart is archival footage coupled with a rare one-on-one interview with struggles, whether it’s financial pressures, parenthood, or, most recently, the Meredith, the first Black man to enroll at the University of Mississippi. pandemic. You could forgive a sitcom for skipping COVID-19 in its storyline, but by tackling it, The Conners shows us once again that life is messy and Nominees sometimes hard, but with love and humor, we persevere. -

Sunday Morning Grid 5/1/16 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 5/1/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Boss Paid Program PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Rescue Red Bull Signature Series (Taped) Å Hockey: Blues at Stars 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) NBA Basketball First Round: Teams TBA. (N) Basketball 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Woodlands Amazing Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday Midday Prerace NASCAR Racing Sprint Cup Series: GEICO 500. (N) 13 MyNet Paid Program A History of Violence (R) 18 KSCI Paid Hormones Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local 24 KVCR Landscapes Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Martha Pépin Baking Simply Ming 28 KCET Wunderkind 1001 Nights Bug Bites Space Edisons Biz Kid$ Celtic Thunder Legacy (TVG) Å Soulful Symphony 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto Paid Program Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División: Toluca vs Azul República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Schuller In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Formula One Racing Russian Grand Prix. -

March 26 to April 8, 2013 Discovery Channel Primetime Spotlight

March 26 TO April 8, 2013 Discovery Channel Primetime Spotlight Contact: Marilyn Montgomery, 310-975-1630, [email protected] Photos, Videos & Additional Information: http://press.discovery.com SPOTLIGHT: UPCOMING PREMIERES/FINALES/SPECIALS HOW WE INVENTED THE WORLD 4-part special premieres on Tuesday, March 26 at 9PM ET/PT followed by a new episode at 10PM ET/PT How We Invented the World examines four inventions that define the modern world – cell phones, cars, planes, and skyscrapers. Each episode in this 4-part series reveals the fascinating stories and seemingly random events that ultimately led to the creation of these iconic inventions. By showcasing the minds behind the innovations that have shaped our lives in unimaginable and unanticipated ways, this series highlights stories of human ingenuity, extraordinary connections, unprecedented experimentation, and jaw-dropping events that have shaped the world as we know it. Press Contact: Emily Robinson, [email protected], 212-548-5103 Press Web: http://press.discovery.com/us/dsc/programs/how-we-invented-world/ WEED COUNTRY season finale airs on Wednesday, March 27 at 10PM ET/PT Harvest Hell: The Jackson County and Siskiyou County Sheriff’s Departments are teaming up to take down the biggest grow of the season. Mere miles away Shotwell arrives at Mike Boutin’s house to pick up the weed he feels will put him back on top, but Mike isn’t ready to hand over any weed, having not spoken to Matt since their first meeting. Late at night, Mike’s plants are ripped from the ground and Mike suspects it was his guests who did it. -

Feeling Funny

A U T O HOM E LIFE B U S I N ESS A MEM B E R SER VIC E KYF B.CO M 58 W Walnut Mt. Olivet, KY 41064 P: 606-724-5812 E: [email protected] John DeLong Saturday, May 5, 2018 Agency Manager Ari Graynor in “I’m KENTUCKY FARM BUREAU INSURANCE Feeling Dying Up Here” funny If they say they can do what we can… ask for their credentials. - Story on page 2 - For all the times you need care without the wait Whether it’s care for the flu, infections, minor illnesses, sprains, cuts or burns, Meadowview Regional Urgent Care will make sure you can easily and quickly get the care you need to feel better. We Have You Covered - Without an Appointment Monday thru Friday 6 p.m. - 11 p.m.; Saturday & Sunday 12 p.m. - 6 p.m. Most insurance plans accepted. Payment due at time of service. 606-759-9921 525 Tucker Dr. • Maysville, KY 41056 MeadowviewRegional.com A2 | Saturday, May 5, 2018 The Ledger Independent Cover Story Video releases Fifty Shades Freed Golden age of comedy: ‘I’m Dying Up Here’ returns for season 2 Now happily married, Ana (Johnson) and Christian (Dornan) return early When we were first introduced to By Francis Babin Trying to make waves is Dawn Lima from their exotic and romantic hon- TV Media Goldie (Melissa Leo, “The Fighter,” (Xosha Roquemore, “The Mindy Proj- eymoon after they receive word of a 2010) and the club that bears her name ect”), a fearless preacher’s daughter break-in at Christian’s company tandup comedy is hard, and it’s last season, they were on top of the who has something to prove to herself headquarters. -

TV Listings SATURDAY, MARCH 7, 2015

TV listings SATURDAY, MARCH 7, 2015 08:30 Gold Rush 21:20 Alien Mysteries Witch 06:10 Sweet Genius 11:25 Lewis 09:20 Gold Divers: Under The Ice 22:10 Close Encounters 23:10 Wolfblood 07:00 Tastiest Places To Chowdown 12:10 Lewis 10:10 Alaska: The Last Frontier 22:35 Close Encounters 23:35 Wolfblood 07:25 Diners, Drive-Ins & Dives 13:15 Remember Me 11:00 Street Outlaws 23:00 Alien Encounters 07:50 Diners, Drive-Ins & Dives 14:05 Who’s Doing The Dishes 11:50 American Muscle 23:50 How The Universe Works 08:15 Chopped 15:00 Sunday Night At The Palladium 00:50 River Monsters 12:40 How It’s Made 09:05 Siba’s Table 15:55 The Chase: Celebrity Specials 01:45 Ten Deadliest Snakes 13:05 How It’s Made 09:30 Have Cake, Will Travel 16:50 The Jonathan Ross Show 02:40 Gorilla Doctors 13:30 How It’s Made 09:55 Have Cake, Will Travel 17:45 Ant & Dec’s Saturday Night 03:35 Saving Africa’s Giants With 16:50 Baggage Battles 00:30 Fashion Bloggers 10:20 Barefoot Contessa - Back To Takeaway Yao Ming 17:15 Baggage Battles 00:55 Fashion Bloggers Basics 19:00 Sunday Night At The Palladium 04:25 Tanked 17:40 Backroad Bounty 01:25 #RichKids Of Beverly Hills 10:45 Barefoot Contessa - Back To 19:55 Who’s Doing The Dishes 05:15 Alaskan Bush People 18:05 Backroad Bounty 01:50 #RichKids Of Beverly Hills Basics 20:50 The Jonathan Ross Show 06:02 Gorilla Doctors 18:30 Backroad Bounty 02:20 E! News 11:10 Siba’s Table 21:45 Ant & Dec’s Saturday Night 06:49 Saving Africa’s Giants With 18:55 The Carbonaro Effect 00:00 Violetta 03:15 Eric And Jessie: Game On 11:35 Siba’s Table -

December 31, 2017 - January 6, 2018

DECEMBER 31, 2017 - JANUARY 6, 2018 staradvertiser.com WEEKEND WAGERS Humor fl ies high as the crew of Flight 1610 transports dreamers and gamblers alike on a weekly round-trip fl ight from the City of Angels to the City of Sin. Join Captain Dave (Dylan McDermott), head fl ight attendant Ronnie (Kim Matula) and fl ight attendant Bernard (Nathan Lee Graham) as they travel from L.A. to Vegas. Premiering Tuesday, Jan. 2, on Fox. Join host, Lyla Berg, as she sits down with guests Meet the NEW SHOW WEDNESDAY! who share their work on moving our community forward. people SPECIAL GUESTS INCLUDE: and places Mike Carr, President & CEO, USS Missouri Memorial Association that make Steve Levins, Executive Director, Office of Consumer Protection, DCCA 1st & 3rd Wednesday Dr. Lynn Babington, President, Chaminade University Hawai‘i olelo.org of the Month, 6:30pm Dr. Raymond Jardine, Chairman & CEO, Native Hawaiian Veterans Channel 53 special. Brandon Dela Cruz, President, Filipino Chamber of Commerce of Hawaii ON THE COVER | L.A. TO VEGAS High-flying hilarity Winners abound in confident, brash pilot with a soft spot for his (“Daddy’s Home,” 2015) and producer Adam passengers’ well-being. His co-pilot, Alan (Amir McKay (“Step Brothers,” 2008). The pair works ‘L.A. to Vegas’ Talai, “The Pursuit of Happyness,” 2006), does with the company’s head, the fictional Gary his best to appease Dave’s ego. Other no- Sanchez, a Paraguayan investor whose gifts By Kat Mulligan table crew members include flight attendant to the globe most notably include comedic TV Media Bernard (Nathan Lee Graham, “Zoolander,” video website “Funny or Die.” While this isn’t 2001) and head flight attendant Ronnie the first foray into television for the produc- hina’s Great Wall, Rome’s Coliseum, (Matula), both of whom juggle the needs and tion company, known also for “Drunk History” London’s Big Ben and India’s Taj Mahal demands of passengers all while trying to navi- and “Commander Chet,” the partnership with C— beautiful locations, but so far away, gate the destination of their own lives. -

October 13 - 19, 2019

OCTOBER 13 - 19, 2019 staradvertiser.com HIP-HOP HISTORY Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson and Tariq “Black Thought” Trotter discuss the origins and impact of iconic hip-hop anthems in the new six-part docuseries Hip Hop: The Songs That Shook America. The series debut takes a look at Kanye West’s “Jesus Walks,” a Christian rap song that challenged religion. Premiering Sunday, Oct. 13, on AMC. Join host, Lyla Berg as she sits down with guests Meet the NEW EPISODE! who share their work on moving our community forward. people SPECIAL GUESTS INCLUDE: and places Rosalyn K.R.D. Concepcion, KiaҊi Loko AlakaҊi Pond Manager, Waikalua Loko IҊa that make 1st & 3rd Kevin P. Henry, Regional Communications Manager, Red Cross of HawaiҊi Hawai‘i Wednesday of the Month, Matt Claybaugh, PhD, President & CEO, Marimed Foundation 6:30 pm | Channel 53 olelo.org special. Greg Tjapkes, Executive Director, Coalition for a Drug-Free Hawaii ON THE COVER | HIP HOP: THE SONGS THAT SHOOK AMERICA Soundtrack of a revolution ‘Hip Hop: The Songs That “Hip-hop was seen as a low-level art form, or BlackLivesMatter movement. Rapper Pharrell Shook America’ airs on AMC not even seen as actual art,” Questlove said. Williams, the song’s co-producer, talked about “People now see there’s value in hip-hop, but I the importance of tracing hip-hop’s history in feel like that’s based on the millions of dollars a teaser for “Hip Hop: The Songs That Shook By Kyla Brewer it’s generated. Like its value is like that of junk America” posted on YouTube this past May. -

The Pacific Coast and the Casual Labor Economy, 1919-1933

© Copyright 2015 Alexander James Morrow i Laboring for the Day: The Pacific Coast and the Casual Labor Economy, 1919-1933 Alexander James Morrow A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2015 Reading Committee: James N. Gregory, Chair Moon-Ho Jung Ileana Rodriguez Silva Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Department of History ii University of Washington Abstract Laboring for the Day: The Pacific Coast and the Casual Labor Economy, 1919-1933 Alexander James Morrow Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor James Gregory Department of History This dissertation explores the economic and cultural (re)definition of labor and laborers. It traces the growing reliance upon contingent work as the foundation for industrial capitalism along the Pacific Coast; the shaping of urban space according to the demands of workers and capital; the formation of a working class subject through the discourse and social practices of both laborers and intellectuals; and workers’ struggles to improve their circumstances in the face of coercive and onerous conditions. Woven together, these strands reveal the consequences of a regional economy built upon contingent and migratory forms of labor. This workforce was hardly new to the American West, but the Pacific Coast’s reliance upon contingent labor reached its apogee after World War I, drawing hundreds of thousands of young men through far flung circuits of migration that stretched across the Pacific and into Latin America, transforming its largest urban centers and working class demography in the process. The presence of this substantial workforce (itinerant, unattached, and racially heterogeneous) was out step with the expectations of the modern American worker (stable, married, and white), and became the warrant for social investigators, employers, the state, and other workers to sharpen the lines of solidarity and exclusion. -

Country Carpet

PAGE SIX-BFOUR-B TTHURSDAYHURSDAY, ,F AEBRUARYUGUST 23, 2, 20122012 THE LICKING VALLEYALLEY COURIER Stop By Speedy Your Feed Frederick & May Elam’sElam’s FurnitureFurnitureCash SpecialistsYour Feed For All YourStop Refrigeration By New & Used Furniture & AppliancesCheck Specialists NeedsFrederick With A Line& May Of QUALITY FrigidaireFor All Your 2 Miles West Of West Liberty - Phone 743-4196 Safely and Comfortably Heat 500, 1000, to 1500 sq. Feet For Pennies Per Day! 22.6 Cubic Feet Advance QUALITYFEED RefrigerationAppliances. Needs With A iHeater PTC Infrared Heating Systems!!! $ 00 •Portable 110V FEED Line Of Frigidaire Appliances. We hold all customer Regular FOR ALL Remember We 999 •Superior Design and Quality • All Popular Brands • Custom Feed Blends Need Cash? Checks for 30 days! Price •Full Function Credit Card Sized FORYOUR ALL ServiceRemember What We We Service Sell! 22.6 Cubic Feet Remote Control •• All Animal Popular Health Brands Products • Custom Feed Blends •Available in Cherry & Black Finish YOURFARM $ 00 $379 •• Animal Pet Food Health & Supplies Products •Horse Tack What We Sell! Speedy Cash •Reduces Energy Usage by 30-50% 999 Sale •Heats Multiple Rooms •• Pet Farm Food & Garden & Supplies Supplies •Horse Tack ANIMALSFARM Price •1 Year Factory Warranty •• FarmPlus Ole & GardenYeller Dog Supplies Food Frederick & May Brentny Cantrell •Thermostst Controlled ANIMALS $319 •Cannot Start Fires • Plus Ole Yeller Dog Food Frederick & May 1209 West Main St. No Glass Bulbs •Child and Pet Safe! Lyon Feed of West Liberty Lumber Co., Inc. West Liberty, KY 41472 ALLAN’S TIRE SUPPLY, INC. Lyon(Moved Feed To New Location of West Behind Save•A•Lot)Liberty 919 PRESTONSBURG ST. -

Sunday Morning Grid 3/1/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 3/1/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Bull Riding College Basketball 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å Snowboarding U.S. Grand Prix: Slopestyle. (Taped) Red Bull Series PGA Tour Golf 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Explore This Week News (N) NBA Basketball Clippers at Chicago Bulls. (N) Å Basketball 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday NASCAR Racing Sprint Cup Series: Folds of Honor QuikTrip 500. (N) 13 MyNet Paid Program Swimfan › (2002) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR T’ai Chi, Health JJ Virgin’s Sugar Impact Secret (TVG) Deepak Chopra MD Suze Orman’s Financial Solutions for You (TVG) 28 KCET Raggs New. Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Rick Steves’ Europe: A Cultural Carnival Over Hawai’i (TVG) Å 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY7) Doki (TVY7) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly Uncle Buck ›› (1989) 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Al Punto (N) Fútbol Central (N) Mexico Primera Division Soccer: Toluca vs Azul República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B.