Criminal Liability for Maritime Disasters Causing Death in Australian Territorial Waters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Index to Marrickville Heritage Society Inc Newsletter Issn 0818-0695

INDEX TO MARRICKVILLE HERITAGE SOCIETY INC NEWSLETTER ISSN 0818-0695 Vol 1 No 1 June 1984 To Vol 25 No 10 June 2009 Compiled by Robert Thompson The first issue of Marrickville Heritage Society’s Newsletter appeared in June 1984, just a short time after the formation of the Society. That first issue boldly declared itself to be vol 1 no 1. That we are now able to present an index to Volumes 1 to 25 is due to the determination and skill of each of the editors and contributors who have continued to produce a publication of such high quality. An early decision taken by members of the Society was that it should be an active organisation, rather than a remote one where members would simply pay their subscriptions and leave all the work to a committee. Because of its superb program of activities it has become a true ‘society’. The resulting comradeship has seen members working together to preserve not only the built environment of Marrickville but, perhaps more importantly, our social history as well. The story of Marrickville’s people is a vibrant, ongoing one in which each of us continues to play a part. And while members’ research will uncover and document more of our past, the initiatives and activities of Marrickville Heritage Society will ensure its relevance to a wider society, encouraging the protection of our heritage into the future. The Newsletter records each of our excursions and the speakers – from within and outside the Society – who have entertained and informed us; the fascinating, the horrifying and the sometimes bizarre in Marrickville’s unique story. -

Marriageability and Indigenous Representation in the White Mainstream Media in Australia

Marriageability and Indigenous Representation in the White Mainstream Media in Australia PhD Thesis 2007 Andrew King BA (Hons) Supervisor: Associate Professor Alan McKee Creative Industries, Queensland University of Technology Abstract By means of a historical analysis of representations, this thesis argues that an increasing sexualisation of Indigenous personalities in popular culture contributes to the reconciliation of non-Indigenous and Indigenous Australia. It considers how sexualised images and narratives of Indigenous people, as they are produced across a range of film, television, advertising, sport and pornographic texts, are connected to a broader politics of liberty and justice in the present postmodern and postcolonial context. By addressing this objective the thesis will identify and evaluate the significance of ‘banal’ or everyday representations of Aboriginal sexuality, which may range from advertising images of kissing, television soap episodes of weddings, sultry film romances through to more evocatively oiled-up representations of the pin- up-calendar variety. This project seeks to explore how such images offer possibilities for creating informal narratives of reconciliation, and engendering understandings of Aboriginality in the media beyond predominant academic concerns for exceptional or fatalistic versions. i Keywords Aboriginality Indigenous Marriageability Reconciliation Popular Culture Sexuality Relationships Interracial Public Sphere Mediasphere Celebrity ii Table of Contents Introduction …………………………………………………………………………. -

21961 Notices of Motions and Orders of The

21961 PARLIAMENT OF NEW SOUTH WALES LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY 2003-06 FIRST SESSION OF THE FIFTY-THIRD PARLIAMENT ___________________ NOTICES OF MOTIONS AND ORDERS OF THE DAY No. 172 TUESDAY 4 APRIL 2006 ___________________ GOVERNMENT BUSINESS NOTICES OF MOTION— 1 Mr IEMMA to move— That leave be given to bring in a bill for an Act to protect the rights of victims of asbestos products of the James Hardie corporate group to obtain compensation despite the restructuring of that group and to provide for the winding up and external administration of former subsidiaries of that group; and for other purposes. (James Hardie (Imposition of Corporate Responsibility) Bill). (Notice given 30 November 2005) ORDERS OF THE DAY— 1 National Parks and Wildlife (Adjustment of Areas) Bill; resumption of the adjourned debate, on the motion of Ms Nori, “That this bill be now read a second time” (from 28 February 2006—Mr Maguire). 21962 BUSINESS PAPER Tuesday 4 April 2006 2 Fisheries Management Amendment Bill; resumption of the adjourned debate, on the motion of Mr Campbell, “That this bill be now read a second time” (from 28 February 2006—Mr George). 3 Protection of the Environment Operations Amendment (Waste Reduction) Bill; resumption of the adjourned debate, on the motion of Mr Debus, “That this bill be now read a second time” (from 8 March 2006—Mr Maguire). 4 Environmental Planning and Assessment Amendment (Reserved Land Acquisition) Bill; resumption of the adjourned debate, on the motion of Mr Sartor, “That this bill be now read a second time” (from 28 March 2006—Mr George). -

21013 Notices of Motions and Orders of The

21013 PARLIAMENT OF NEW SOUTH WALES LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY 2003-06 FIRST SESSION OF THE FIFTY-THIRD PARLIAMENT ___________________ NOTICES OF MOTIONS AND ORDERS OF THE DAY No. 169 TUESDAY 28 MARCH 2006 ___________________ GOVERNMENT BUSINESS NOTICES OF MOTION— 1 Mr DEBUS to move— That leave be given to bring in a bill for an Act to amend the Crimes Act 1900 to make further provision with respect to theft of motor vehicles and vessels, and their parts; to amend other Acts consequentially; and for other purposes. (Crimes Amendment (Organised Car and Boat Theft) Bill). (Notice given 9 March 2006) 21014 BUSINESS PAPER Tuesday 28 March 2006 2 Mr IEMMA to move— That leave be given to bring in a bill for an Act to protect the rights of victims of asbestos products of the James Hardie corporate group to obtain compensation despite the restructuring of that group and to provide for the winding up and external administration of former subsidiaries of that group; and for other purposes. (James Hardie (Imposition of Corporate Responsibility) Bill). (Notice given 30 November 2005) ORDERS OF THE DAY— 1 Air Transport Amendment Bill; resumption of the adjourned debate, on the motion of Mr Watkins, “That this bill be now read a second time” (from 28 February 2006—Mr Maguire). 2 National Parks and Wildlife (Adjustment of Areas) Bill; resumption of the adjourned debate, on the motion of Ms Nori, “That this bill be now read a second time” (from 28 February 2006—Mr Maguire). 3 Child Protection (International Measures) Bill; resumption of the adjourned debate, on the motion of Ms Meagher, “That this bill be now read a second time” (from 28 February 2006—Mr George). -

1951 Aug GIRLS

THE MAGAZINE OF THE FORT STREET GIRLS’ HIGH SCHOOL Volume V., No. 9. August, 1951 r The Magazine of tho Jart Street ®trls’ litali School AUGUST, 1951. FABER EST SUAE QUISQUE FORTUNAE. THE STAFF. Principal: Miss F. COHEN, M.A., B.Sc. DepuUj-Principal: Miss B. SMITH, B.A. Dejiartmcnt of English: Miss D. DEY, M.A. (Mistress). Miss D. CROXON, B.A. Miss E. COCHRANE, B.A. Miss B. ROBERTS, B.A. Ì Mrs. M. CRADDOCK, B.A. Miss R. TRANT-FISCHER, M.A. Miss K. CROOKS, B.A. Department of Classics: Miss M. GLANVILLE, B.A. Department of Mathematics : Miss E. KERR, B.A. (Mistress). Miss I. GREEN, B.A. Miss K. CONNOLLY, B.Sc. Miss D. LLEWELLYN, B.Sc., B.Ec. Miss H. GORDON, B.Sc. Mrs. B. MURPHY, B.Sc. Department of Science: Miss A. PUXLEY. B.Sc. (Mistress). Miss V. HUNT, B.Sc Miss M. CHEETHAM, B.A. Miss V. McMULLEN, B.Sc. Miss J. CRAWFORD. B.A. Mrs. B. MURPHY, B.Sc. Department of Modern Dangaages: Miss B. MITCHELL. B.A. (Mistress). Miss M. KENT HUGHES, M.A. (Vic). Miss L. ARTER, B A. Mrs. M. PATTERSON. B.A. Mrs. M. CRADDOCK, B.A. Miss B. SMITH, B.A. Art: Miss J. PALFREY. Needlework: Miss J- BURTON. Music: Mrs. J. MURRAY, A.Mus.A., T.D.S.C.M. School Counsellor : Miss J. ROBINSON, B.A. Physical Training: Miss N. ANDERSON. Miss E. STERN, Dip. Phys. Ed. Magazine Editor: M iss D. DEY, M.A. Sub-Editor: Miss K. CROOKS. B.A. School Captain: ROSEMARY RANDALL. -

![Scope [Skohp] Noun, Verb, Scoped, Scoping](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3049/scope-skohp-noun-verb-scoped-scoping-3253049.webp)

Scope [Skohp] Noun, Verb, Scoped, Scoping

scope [skohp] noun, verb, scoped, scoping extent or range of view, outlook, operation, effectiveness, etc. space for movement or activity; opportunity for operation: to give one’s fancy full scope. extent in space, a tract or area. aim or purpose Liguisitics, logic, the range or words or elements of an expression over which DPRGLÀHURURSHUDWRUKDVFRQWURO (used as a short form of PLFURVFRSHRVFLORVFRSHSHULVFRSHUDGDUVFRSHULÁHVFRSH telescopic sight etc.) Slang. to look at, read, or investigate, as in order to appreciate or evaluate. scope out, slang. to look at or over; examine; check out. the range of one’s perceptions, thoughts, or actions. SCOPE 2007 Hi there... Meet Scope ‘07 . d f He’s ha an interesting li e... Born in war-torn Sierra Leone, he fled to Australia, he was HOMELESS for a while, living at a beach, before going to a COMEDY CLUB and doing some stand-up. He has a brother WITH AUTISM, a relative with dementia and a war-heroine grandma Norwegian . Scope07 has worked in a shoe shop, a chicken abattoir, & as a busker. ONE DAY the world and his apathetic generation, , angry at he w patch. He bec ent through a bad ame addicted to Crystal Meth and late r had to go to He tried to findMILITARY salvation a COURT. Convention so Scope’07 t Hillsong To hear and joined the , but it wasn’t for him, pa went to ge and start readin MORE religion ofDENMARK of to a g.... Scope’07’s Harry Potter.Fan adventures, Lena Lowe, SCOPE07’SWilla McDonald, BEST Christine FRIENDS Jones, ARE:Anne and Greg McDonald, Mac Coffee Cart, all the lovely student authors tu rn the SCOPE‘07 WAS GENEROUSLY ACCESSORISED a BY THE FOLLOWINGand dictionary.comPHOTOGRAPHERS AND t F Carrie Barbash, Dustin Glick, Lisa Bunker, Samuel Groves, fe Helen Davidson, Angela Nicholls, Anson Fehross, iStock. -

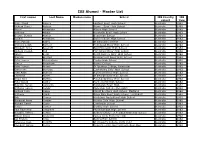

ISS Alumni - Master List

ISS Alumni - Master List First names Last Name Maiden name School ISS Country ISS cohort Year Brian David Aarons Fairfield Boys' High School Australia 1962 Richard Daniel Aldous Narwee Boys' High School Australia 1962 Alison Alexander Albury High School Australia 1962 Anthony Atkins Hurstville Boys' High School Australia 1962 George Dennis Austen Bega High School Australia 1962 Ronald Avedikian Enmore Boys' High School Australia 1962 Brian Patrick Bailey St Edmund's College Australia 1962 Anthony Leigh Barnett Homebush Boys' High School Australia 1962 Elizabeth Anne Beecroft East Hills Girls' High School Australia 1962 Richard Joseph Bell Fort Street Boys' High School Australia 1962 Valerie Beral North Sydney Girls' High School Australia 1962 Malcolm Binsted Normanhurst Boys' High School Australia 1962 Peter James Birmingham Casino High School Australia 1962 James Bradshaw Barker College Australia 1962 Peter Joseph Brown St Ignatius College, Riverview Australia 1962 Gwenneth Burrows Canterbury Girls' High School Australia 1962 John Allan Bushell Richmond River High School Australia 1962 Christina Butler St George Girls' High School Australia 1962 Bruce Noel Butters Punchbowl Boys' High School Australia 1962 Peter David Calder Hunter's Hill High School Australia 1962 Malcolm James Cameron Balgowlah Boys' High Australia 1962 Anthony James Candy Marcellan College, Randwich Australia 1962 Richard John Casey Marist Brothers High School, Maitland Australia 1962 Anthony Ciardi Ibrox Park Boys' High School, Leichhardt Australia 1962 Bob Clunas -

Cloudland, Stronzoland, Brisbane: Urban Development and Ethnic Bildung in Venero Armanno’S Fiction

CLOUDLAND, STRONZOLAND, BRISBANE: URBAN DEVELOPMENT AND ETHNIC BILDUNG IN VENERO ARMANNO’S FICTION Jessica Carniel Abstract The evolving urban landscape of Brisbane becomes a significant presence in Venero Armanno’s fiction, distinct from the often more documented sites of Sydney, Melbourne. The use of Brisbane as the setting for Armanno’s novels is significant in that this city, like the characters he creates within it, is often seen as being in search for its own culture and identity, having grown up in the shadow of the reputedly more cosmopolitan eastern coast capital cities of Sydney and Melbourne. Brisbane’s recovery from its somewhat shady past involving corrupt government and law enforcement echoes the journey upon which Armanno’s protagonists embark. Furthermore, Brisbane, especially the suburbs of New Farm and Fortitude Valley featured in Armanno’s works, acts as a symbolic Little Italy to which the protagonists might retreat in search of their ethnic beginnings. Questions of community and identity are intrinsic to the urban landscape through which the protagonist travels in their quest for Bildung . Focussing on the three of Armanno’s fictional works set in the city of Brisbane and using critical definitions of Bildung and the notion of ethnic Bildungsromane , this paper aims to examine the parallel development of the Italian Australian protagonists and their urban environments. Brisbane is so sleepy, so slatternly, so sprawlingly unlovely! I have taken to wandering about after school looking for one simple object in it that might be romantic, or appalling even, but there is nothing. It is simply the most ordinary place in the world. -

MEDIA KIT As at 22.8.16

Screen Australia and Seven Network present A Screentime Production MEDIA KIT As at 22.8.16 NETWORK PUBLICIST Elizabeth Johnson T 02 8777 7254 M 0412 659 052 E [email protected] ABOUT THE PRODUCTION Screen Australia and Seven Network present a Screentime, a Banijay Group company, production The Secret Daughter produced with the assistance of Screen Australia and Screen NSW. The major new drama for Channel Seven - THE SECRET DAUGHTER starring Jessica Mauboy, was filmed in Sydney and country NSW. The ARIA and AACTA award-winning singer and actress leads the cast as Billie Carter, a part- time country pub singer whose life changes forever after a chance meeting with wealthy city hotelier Jack Norton, played by acting great Colin Friels. Bonnie Sveen (Home and Away) plays Billie’s best friend Layla. The feel-good drama also stars Matt Levett (A Place To Call Home, Devil’s Playground), David Field (Catching Milat, No Activity), Rachel Gordon (Winter, The Moodys, Blue Heelers), Salvatore Coco (Catching Milat, The Principal), Jared Turner (The Almighty Johnsons, The Shannara Chronicles) and outstanding newcomer Jordan Hare. Supporting cast members include former Miss World Australia Erin Holland, J.R. Reyne (Neighbours), Libby Asciak (Here Come The Habibs), Johnny Boxer (Fat Pizza vs Housos), Terry Serio (Janet King), Jeremy Ambrum (Cleverman, Mabo) and Amanda Muggleton (City Homicide, Prisoner). Seven’s Director of Network Production, Brad Lyons, said: “Seven is the home of Australian drama and we’re immensely proud to be bringing another great Australian story to the screen. Jessica Mauboy is an amazing talent and this is a terrific yarn full of warmth, humour and music and we can’t wait to share it with everyone.” Screentime CEO Rory Callaghan, added: "We are delighted that this heart-warming production has attracted a cast of such depth and calibre.” THE SECRET DAUGHTER is a Screentime, a Banijay Group company, production for Channel Seven produced with the financial assistance of Screen Australia and Screen NSW. -

P-Plater Restrictions 'Need Some Rethinking': NRDSC

THE BYRON SHIRE ECHO Advertising & news enquiries: Mullumbimby 02 6684 1777 Byron Bay 02 6685 5222 Back Fax 02 6684 1719 [email protected] [email protected] to http://www.echo.net.au VOLUME 21 #31 TUESDAY, JANUARY 16, 2007 School! 22,300 copies every week *>}iÃÊ£ÈÊE棂 $1 at newsagents only DO NOT FOLD UNDER PRESSURE P-plater restrictions ‘need Woodchop fest a cut above some rethinking’: NRDSC The Northern Rivers Social Devel- the hours of 11pm and 5am would education and recreation. Impor- opment Council (NRSDC) says it be unreasonable for some P-plat- tantly we must avoid a situation is pleased that the debate on road ers, particularly where there is no where novice drivers are forced safety is being taken seriously by public transport alternative in rural into breaking the law in order to the NSW Minister for Roads Eric areas,’ said NRSDC president transport themselves and friends Roozendaal, who will introduce Jenny Dowell. ‘Driving family simply because there are no other new restrictions on P-plate drivers, members, travelling to work or viable alternatives. however NRSDC calls for the community commitments such as ‘As the government moves to debate to be widened to discuss SES or rural fi re fi ghting and driv- toughen conditions for P-plate and offer viable, safe alternatives, ing in an emergency are appropri- drivers, particularly at night, they such as better public transport ate exemptions.’ also must guarantee that there will options for everyone in rural and ‘There are few transport options be suitable alternatives available, regional areas. -

What About Me?: Identity, Subjectivity and Reality TV Participation

What about me? Identity, subjectivity and reality TV participation Winnie Salamon Submitted in total fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy November 2010 School of Culture and Communication University of Melbourne 2 Abstract This thesis examines first person accounts of former reality television participants who have appeared on Australian versions of Big Brother , Australian Idol and The Biggest Loser . While scholars have researched audience responses to a wide range of reality shows, little research has been conducted on the participants themselves. My qualitative research study involving 15 semi-structured one-on-one interviews with reality TV participants addresses this gap, using these accounts to explore broader issues surrounding late modern identity and subjectivity. 3 Declaration This is to certify that 1. the thesis comprises only my original work 2. due acknowledgement has been made in the text to all material used 3. the thesis is less than 100,000 words in length, exclusive of bibliography Winnie Salamon 4 Table of Contents Acknowledgements Introduction 6 Chapter One 15 Reality TV and our collective selves: a history and review of the literature Chapter Two 52 Qualitative research and reflexivity: interviewing through an ethnographic gaze Chapter Three 77 ‘There’s no reality in reality TV’: performing the real in a ‘reality flavoured’ universe Chapter Four 110 What about me? Reality TV and the self-governed citizen Chapter Five 149 Brand new world: reality TV and the branded human Chapter Six 179 Reality is a bitch: expectations and disappointments in reality TV participation Chapter Seven 212 Hijacking the branded self: reality TV and the politics of subversion Conclusion 239 Appendix 1: The interviewees 245 Appendix 2: Interview questions 249 Bibliography 252 5 Acknowledgments This thesis would not have been possible without the tireless support, encouragement and guidance of my supervisor, Dr Carolyne Lee. -

The Triangle

THE TRIANGLE 2016 THE MAGAZINE OF TRINITY GRAMMAR SCHOOL THE TRIANGLE TRINITY GRAMMAR SCHOOL 2016 SUMMER HILL SENIOR, MIDDLE AND JUNIOR SCHOOLS STRATHFIELD PREPARATORY SCHOOL WOOLLAMIA FIELD STUDIES CENTRE FOUNDER THE RT. REV. G. A. CHAMBERS, O. B. E., D. D. SCHOOL PRAYER MISSION STATEMENT Heavenly Father, Trinity aims to provide its boys with a thoroughly Christian education, which recognises the importance We ask your blessing of spiritual qualities in every sphere of learning and upon all who work living. Its commitment to academic excellence, pastoral in and for this School. care and participation in a breadth of sporting activities, creative and performing arts promotes a rich cultural Grant us faith to grow spiritually, ethos and develops the individual talents of each boy in Strength to grow bodily, Mind, Body and Spirit. A wide-ranging curriculum caters for both the intellectually gifted and those interested in And wisdom to grow intellectually, vocational courses, and is arguably the most extensive of Through Jesus Christ our Lord, Amen. non-selective Independent Boys Schools in NSW. CONTENTS SENIOR AND MIDDLE SCHOOLS PREPARATORY SCHOOL JUNIOR SCHOOL 3rd Summer Hill Scout Group 129 Music Competitions 116 3rd Summer Hill Scout Group 129 3rd Summer Hill Scout Group 129 Academic Dean 32 Music Concerts 116 Basketball 230 Basketball 268 Academy of Music 112 Music Quartets 123 Captain's Report 210 Captain's Report 248 Activities Master's Report 92 Music Trios 122 Chapel 212 Chess 256 AFL 139 Old Trinitarians' Union Report 49 Chess 219