Dressing Cinderella: an Exploration of Women's Engagement with And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Volume 2, Issue 3, Autumn 2018

The Journal of Dress History Volume 2, Issue 3, Autumn 2018 Front Cover Image: Textile Detail of an Evening Dress, circa 1950s, Maker Unknown, Middlesex University Fashion Collection, London, England, F2021AB. The Middlesex University Fashion Collection comprises approximately 450 garments for women and men, textiles, accessories including hats, shoes, gloves, and more, plus hundreds of haberdashery items including buttons and trimmings, from the nineteenth century to the present day. Browse the Middlesex University Fashion Collection at https://tinyurl.com/middlesex-fashion. The Journal of Dress History Volume 2, Issue 3, Autumn 2018 Editor–in–Chief Jennifer Daley Editor Scott Hughes Myerly Proofreader Georgina Chappell Published by The Association of Dress Historians [email protected] www.dresshistorians.org The Journal of Dress History Volume 2, Issue 3, Autumn 2018 [email protected] www.dresshistorians.org Copyright © 2018 The Association of Dress Historians ISSN 2515–0995 Online Computer Library Centre (OCLC) accession #988749854 The Journal of Dress History is the academic publication of The Association of Dress Historians through which scholars can articulate original research in a constructive, interdisciplinary, and peer reviewed environment. The Association of Dress Historians supports and promotes the advancement of public knowledge and education in the history of dress and textiles. The Association of Dress Historians (ADH) is Registered Charity #1014876 of The Charity Commission for England and Wales. The Journal of Dress History is copyrighted by the publisher, The Association of Dress Historians, while each published author within the journal holds the copyright to their individual article. The Journal of Dress History is circulated solely for educational purposes, completely free of charge, and not for sale or profit. -

Index to Marrickville Heritage Society Inc Newsletter Issn 0818-0695

INDEX TO MARRICKVILLE HERITAGE SOCIETY INC NEWSLETTER ISSN 0818-0695 Vol 1 No 1 June 1984 To Vol 25 No 10 June 2009 Compiled by Robert Thompson The first issue of Marrickville Heritage Society’s Newsletter appeared in June 1984, just a short time after the formation of the Society. That first issue boldly declared itself to be vol 1 no 1. That we are now able to present an index to Volumes 1 to 25 is due to the determination and skill of each of the editors and contributors who have continued to produce a publication of such high quality. An early decision taken by members of the Society was that it should be an active organisation, rather than a remote one where members would simply pay their subscriptions and leave all the work to a committee. Because of its superb program of activities it has become a true ‘society’. The resulting comradeship has seen members working together to preserve not only the built environment of Marrickville but, perhaps more importantly, our social history as well. The story of Marrickville’s people is a vibrant, ongoing one in which each of us continues to play a part. And while members’ research will uncover and document more of our past, the initiatives and activities of Marrickville Heritage Society will ensure its relevance to a wider society, encouraging the protection of our heritage into the future. The Newsletter records each of our excursions and the speakers – from within and outside the Society – who have entertained and informed us; the fascinating, the horrifying and the sometimes bizarre in Marrickville’s unique story. -

February 2012

The Park Press Winter Park | Baldwin Park | College Park | M a i t l a n d F E b R u a R y 2 0 1 2 FREE Duck Derby a Makeover Technology Winner allows Creativity 10 15 18 It’s Great To be Grand! – by Tricia Cable Teachers, in general, are some of the the doctor’s visits, helping to pay for med- most thoughtful human beings on the icine, paying for children with impaired planet. They certainly don’t become vision to get glasses, and on occasion, pay- teachers because of the pay, and many of ing their rent to avoid eviction. the professional educators in my circle But the team of five woman who take spend a great deal of their hard-earned on the responsibility to educate the 88 5 wages on classroom supplies and oth- and 6-year-olds who attend kindergarten er items in an effort to be the very best there are not only incredibly dedicated and teachers for our children. John F. Ken- competent, but also a very compassionate nedy once said “Our progress as a nation and caring group. “Students here are such can be no swifter than our progress in sweet and inquisitive boys and girls,” ex- education. The human mind is our fun- plains team leader Sarah Schneider. “They damental resource.” tend to lack the knowledge of the world The kindergarten team at Grand Av- beyond their own neighborhood, and that enue Primary Learning Center takes that Kindergarten Team Leader Sarah Schneider with a group of her is where we come in,” she continues. -

Polish Musicians Merge Art, Business the INAUGURAL EDITION of JAZZ FORUM SHOWCASE POWERED by Szczecin Jazz—Which Ran from Oct

DECEMBER 2019 VOLUME 86 / NUMBER 12 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Andy Hermann, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow; South Africa: Don Albert. -

34 Underlines

SHAPING TODAY & TOMOROW UNDERLINES ONCE AGAIN TAKES AN INDEPTH LOOK AT THE SUPPLY AND DEMAND CHAIN FOR SHAPING GARMENTS, PARTICULARLY HOW THE MARKET HAS EVOLVED IN THE LAST 12 MONTHS, BY TALKING SIMULTANEOUSLY TO RETAILERS (BOTH LARGE AND SMALL CHAINS AND INDEPENDENT SHOPS*) AND TO LARGE ESTABLISHED SHAPEWEAR PRODUCERS AND NEW BRANDS EMERGING IN THE MARKET. HERE WE REVEAL OUR FINDINGS AND THEY PRODUCE SOME INTERESTING INDICATORS FOR THE FUTURE OF SHAPEWEAR SECTOR. 20% of our respondents this year were large stores or small chains with the 80% balance being represented by specialists and independent shops. Over 50% of all those interviewed have been selling shapewear in some form for over 15 years. However the number of brands represented (even in larger stores) is more restricted than in previous years: 50% sold up to 3 brands with 50% selling between 4-6 brands. WHICH FUNCTIONAL SHAPING UNDERWEAR BRANDS ARE YOUR BESTSELLERS? BRAND NAME % INDICATED AS BESTSELLER MIRACLESUIT 32% SPANX 24% BODYWRAP 16% ELOMI/FANTASIE 12% MAIDENFORM 10% BODYWRAP 10% NAOMI & NICOLE 6% TRIUMPH 6% CONTOURELLE/FELINA 4% CETTE SLIMSHAPERS 2% Note: figures do not equal 100% as respondents could identify more than one bestseller In common with the last 4-5 years American functional brands of shapewear take the top slots. Yummie Cameo high waisted shaping briefs 34 underlines WHICH FASHIONABLE SHAPING UNDERWEAR BRANDS ARE YOUR BESTSELLERS? BRAND NAME % INDICATED AS BESTSELLER PRIMADONNA/VAN DE VELDE 10% IMPLICITE 8% WACOAL 6% PASSIONATA/CHANTELLE 6% WOLFORD 2% 38% of those surveyed said they did not believe they sold shapewear which could be regarded as fashionable. -

Criminal Liability for Maritime Disasters Causing Death in Australian Territorial Waters

YOU’RE A CROOK, CAPTAIN HOOK: CRIMINAL LIABILITY FOR MARITIME DISASTERS CAUSING DEATH IN AUSTRALIAN TERRITORIAL WATERS ALEXANDER M MCVEY This thesis is presented for the Honours degree of Bachelor of Laws of Murdoch University. The author hereby declares that it is his own account of his research. 15,149 words (excluding title pages, table of contents, footnotes and bibliography) 2015 To Linda, who encouraged my curious mind, and to Matt and Leanne who still do. I am truly grateful to my supervisor, Dr Kate Lewins, for her guidance and support. ABSTRACT The world is seeing more maritime disasters every year, in a variety of jurisdictions around the world. Many of these disasters cause a large number of deaths. As a result of those deaths, there is often pressure on the relevant authorities to prosecute the parties responsible. The master of the vessel may be the most obvious party to charge, but there may have been other parties responsible for the operation and management of the vessel whose negligent or reckless conduct contributed to the vessel’s demise. Despite the contributions of other parties, the master of a vessel may become a scapegoat, and, as a result, bear the brunt of any prosecution. There are several reasons why the master may receive the most blame in these situations. One of those may be that the law in force within the relevant jurisdiction does not provide particular criminal charges that apply to parties other than the master. This paper asks whether Australian law encourages prosecuting bodies to scapegoat the master of a vessel and whether this is demonstrative of the wider problem of seafarer criminalisation worldwide. -

Changes in Female Body Shape and Its Effect on the Intimate Apparel Industry

Changes in Female Body Shape and its effect on the Intimate Apparel Industry Abstract With the well-documented changes in women’s body mass index, the future consequences on intimate apparel fashion design cannot be ignored. The theories of fashion may be complex and diverse, but the rapidly increasing average weight of the wealthy western woman may force the return to a curvy fashionable female shape, and since mildly overweight people live longer than those who are too thin, they have more time to enjoy their wardrobe. Recent size surveys in the UK and America have identified body shapes that do not match intimate apparel manufacturer’s block patterns or size charts, thus substantially reducing sales and customer satisfaction. Linking closely to this increased and reshaped body size, is the comfort factor. A trim figure type does not require the engineered fit of her plus sized sister and is unlikely to suffer the abrasive, posture-disturbing outcome of intimate apparel designed to reproduce a fashionable silhouette. Reproduction corsets have run their course so it becomes the task of new technology to offer a pathway between fashion, comfort and shape. The massive worldwide success of the molded cup bra is a fitting example. It does not relate to any fashion theory, aside from its seamless outline, it is a great camouflage device for every woman. It disguises asymmetric body shapes, smoothes fullness or encourages the ego and provides the best business corporate shape. It will be this type of ‘need to wear’ fashion design that will promote the extension of seamless, fused, smart fabric constructions into the new 21st century underwear and performance shapewear. -

Marriageability and Indigenous Representation in the White Mainstream Media in Australia

Marriageability and Indigenous Representation in the White Mainstream Media in Australia PhD Thesis 2007 Andrew King BA (Hons) Supervisor: Associate Professor Alan McKee Creative Industries, Queensland University of Technology Abstract By means of a historical analysis of representations, this thesis argues that an increasing sexualisation of Indigenous personalities in popular culture contributes to the reconciliation of non-Indigenous and Indigenous Australia. It considers how sexualised images and narratives of Indigenous people, as they are produced across a range of film, television, advertising, sport and pornographic texts, are connected to a broader politics of liberty and justice in the present postmodern and postcolonial context. By addressing this objective the thesis will identify and evaluate the significance of ‘banal’ or everyday representations of Aboriginal sexuality, which may range from advertising images of kissing, television soap episodes of weddings, sultry film romances through to more evocatively oiled-up representations of the pin- up-calendar variety. This project seeks to explore how such images offer possibilities for creating informal narratives of reconciliation, and engendering understandings of Aboriginality in the media beyond predominant academic concerns for exceptional or fatalistic versions. i Keywords Aboriginality Indigenous Marriageability Reconciliation Popular Culture Sexuality Relationships Interracial Public Sphere Mediasphere Celebrity ii Table of Contents Introduction …………………………………………………………………………. -

Estta272541 03/17/2009 in the United States Patent And

Trademark Trial and Appeal Board Electronic Filing System. http://estta.uspto.gov ESTTA Tracking number: ESTTA272541 Filing date: 03/17/2009 IN THE UNITED STATES PATENT AND TRADEMARK OFFICE BEFORE THE TRADEMARK TRIAL AND APPEAL BOARD Proceeding 91183558 Party Plaintiff Temple University -- Of the Commonwealth System of Higher Education Correspondence Leslie H Smith Address Liacouras & Smith, LLP 1515 Market Street, Suite 808 Philadelphia, PA 19102 UNITED STATES [email protected] Submission Motion for Summary Judgment Filer's Name Leslie H Smith Filer's e-mail [email protected] Signature /Leslie H Smith/ Date 03/17/2009 Attachments TEMPLE WORKOUT GEAR SJ Motion with Exhibits and Certif of Service.pdf ( 75 pages )(1933802 bytes ) IN THE UNITED STATES PATENT AND TRADEMARK OFFICE BEFORE THE TRADEMARK TRIAL AND APPEAL BOARD In the Matter of Application No. 77/038246 Published in the Official Gazette on December 18, 2007 Temple University – Of The Commonwealth: System of Higher Education, : : Opposer, : Opposition No. 91183558 : v. : : BCW Prints, Inc., : : Applicant. : SUMMARY JUDGMENT MOTION OF OPPOSER TEMPLE UNIVERSITY – OF THE COMMONWEALTH SYSTEM OF HIGHER EDUCATION TABLE OF CONTENTS Page I. INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………… 2 II. UNDISPUTED FACTS……………………………………………………… 3 III. THE UNDISPUTED FACTS ESTABLISH A LIKELIHOOD OF CONFUSION BETWEEN THE TEMPLE MARKS AND OPPOSER’S TEMPLE WORKOUT GEAR (AND DESIGN) TRADEMARK…………… 7 A. Likelihood of Confusion is a Question of Law Appropriate for Summary Judgment………………………………………………………………….. 7 B. Under the du Pont Test, the Undisputed Facts Establish A Likelihood of Confusion between Temple’s TEMPLE Marks and Opposer’s TEMPLE WORKOUT GEAR (and design) Mark…………………………………… 7 1. The TEMPLE Marks and the TEMPLE WORKOUT GEAR (and design) Mark Are Similar in Appearance, Sound, Connotation, and Commercial Impression………………………… 8 2. -

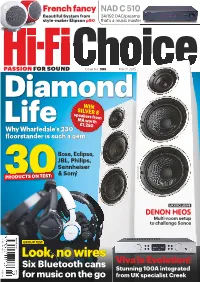

Look, No Wires

French fancy NAD C 510 Beautiful System from 24/192 DAC/preamp style-maker Elipson p90 that’s a music master PASSION FOR SOOUND Issue No. 395 March 2015 Diamond WIN SILVER 8 speakers from MA worth Life £1,250 Why Wharfedale’s 2300 floorstander is such a gem Bose, Eclipse, JBL, Philips, Sennheiser & Sony 30PRODUCTS ON TEST: UK EXCLUSIVE DENON HEOS Multi-room setup to challenge Sonos PRINTED IN THE UK US$13.99 US$13.99 PRINTED IN THE UK £4.50 2015 MARCH GROUP TEST Look, no wires Viva la Evolution! Six Bluetooth cans Stunning 100A integrated for music on the go from UK specialist Creek Our SuperUniti all-in-one player will unleash your digital music, from high- resolution audio files to Spotify playlists. Its analogue heart is an integrated amplifier backed by 40 years of engineering knowledge to offer countless years of musical enjoyment. Just add speakers. SuperUniti. Reference digital music player and integrated amplifier. Next-generation music systems, hand-built in Salisbury, England. Discover more at naimaudio.com INTRODUCTION PASSION FOR SOUND Welcome www.hifichoice.co.uk Issue No. 395 March 2015 Try to imagine for a moment a world without wires connecting your speakers and hi-fi components. It’s a pretty impossible thought for a serious hi-fi fan, right? Most of us see wires like the veins of our hi-fi systems that carry the signal 58 Novafidelity X12 between vital components enabling the music to flow to our speakers, delivering soundwaves to ears, bringing the music to life and feeding our souls. -

21961 Notices of Motions and Orders of The

21961 PARLIAMENT OF NEW SOUTH WALES LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY 2003-06 FIRST SESSION OF THE FIFTY-THIRD PARLIAMENT ___________________ NOTICES OF MOTIONS AND ORDERS OF THE DAY No. 172 TUESDAY 4 APRIL 2006 ___________________ GOVERNMENT BUSINESS NOTICES OF MOTION— 1 Mr IEMMA to move— That leave be given to bring in a bill for an Act to protect the rights of victims of asbestos products of the James Hardie corporate group to obtain compensation despite the restructuring of that group and to provide for the winding up and external administration of former subsidiaries of that group; and for other purposes. (James Hardie (Imposition of Corporate Responsibility) Bill). (Notice given 30 November 2005) ORDERS OF THE DAY— 1 National Parks and Wildlife (Adjustment of Areas) Bill; resumption of the adjourned debate, on the motion of Ms Nori, “That this bill be now read a second time” (from 28 February 2006—Mr Maguire). 21962 BUSINESS PAPER Tuesday 4 April 2006 2 Fisheries Management Amendment Bill; resumption of the adjourned debate, on the motion of Mr Campbell, “That this bill be now read a second time” (from 28 February 2006—Mr George). 3 Protection of the Environment Operations Amendment (Waste Reduction) Bill; resumption of the adjourned debate, on the motion of Mr Debus, “That this bill be now read a second time” (from 8 March 2006—Mr Maguire). 4 Environmental Planning and Assessment Amendment (Reserved Land Acquisition) Bill; resumption of the adjourned debate, on the motion of Mr Sartor, “That this bill be now read a second time” (from 28 March 2006—Mr George). -

Obama Signs LGBT Hospital Access Memo President Calls Lesbian Denied Access to Partner Page 8 by Tracy Baim

THE VOICE OF CHICAGO’S GAY, LESBIAN, BI AND TRANS COMMUNITY SINCE 1985 April 21, 2010 • vol 25 no 29 www.WindyCityMediaGroup.com Gender JUST rally Obama signs LGBT hospital access memo President calls lesbian denied access to partner page 8 BY TRacY Baim “I’m sorry.” Those two little words are what Janice Lang- behn has been waiting to hear since February 2007, when her partner of 18 years, Lisa Pond, just 39 years old, died separated from Langbehn and their children. But the apology did not come from Jack- son Memorial Hospital in Florida, where Pond lay dying from a brain aneurysm suffered Feb. 18, 2007, hours after the family boarded the R Family Cruise. Instead, President Barack Obama said those words to Langbehn in a phone call April 15, 2010, when he phoned her in Olym- pia, Wash., from Air Force One, ironically while it circled over Miami, where Jackson Memorial is Chicago located. Obama called Langbehn to explain a memo he Red Stars page 22 had signed that day to address discrimination LGBT families face from healthcare facilities. The Obama memo directs the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS), Kathleen Sebelius, to move forward on steps to address hospital visitation and other related LGBT healthcare access issues. The resulting regula- tion is expected to require hospitals that receive Turn to page 6 Janice Langbehn (left) and Lisa Pond in 1996. Dan Choi sounds off at Boston gala BY CHUCK COLBERT What should the president do? Choi insists that the president include repeal language in the Mario In the nearly six weeks since his arrest for civil Defense Authorization Act of 2010.