Agency and the Docile Body in the Hunger Games And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2010 16Th Annual SAG AWARDS

CATEGORIA CINEMA Melhor ator JEFF BRIDGES / Bad Blake - "CRAZY HEART" (Fox Searchlight Pictures) GEORGE CLOONEY / Ryan Bingham - "UP IN THE AIR" (Paramount Pictures) COLIN FIRTH / George Falconer - "A SINGLE MAN" (The Weinstein Company) MORGAN FREEMAN / Nelson Mandela - "INVICTUS" (Warner Bros. Pictures) JEREMY RENNER / Staff Sgt. William James - "THE HURT LOCKER" (Summit Entertainment) Melhor atriz SANDRA BULLOCK / Leigh Anne Tuohy - "THE BLIND SIDE" (Warner Bros. Pictures) HELEN MIRREN / Sofya - "THE LAST STATION" (Sony Pictures Classics) CAREY MULLIGAN / Jenny - "AN EDUCATION" (Sony Pictures Classics) GABOUREY SIDIBE / Precious - "PRECIOUS: BASED ON THE NOVEL ‘PUSH’ BY SAPPHIRE" (Lionsgate) MERYL STREEP / Julia Child - "JULIE & JULIA" (Columbia Pictures) Melhor ator coadjuvante MATT DAMON / Francois Pienaar - "INVICTUS" (Warner Bros. Pictures) WOODY HARRELSON / Captain Tony Stone - "THE MESSENGER" (Oscilloscope Laboratories) CHRISTOPHER PLUMMER / Tolstoy - "THE LAST STATION" (Sony Pictures Classics) STANLEY TUCCI / George Harvey – “UM OLHAR NO PARAÍSO” ("THE LOVELY BONES") (Paramount Pictures) CHRISTOPH WALTZ / Col. Hans Landa – “BASTARDOS INGLÓRIOS” ("INGLOURIOUS BASTERDS") (The Weinstein Company/Universal Pictures) Melhor atriz coadjuvante PENÉLOPE CRUZ / Carla - "NINE" (The Weinstein Company) VERA FARMIGA / Alex Goran - "UP IN THE AIR" (Paramount Pictures) ANNA KENDRICK / Natalie Keener - "UP IN THE AIR" (Paramount Pictures) DIANE KRUGER / Bridget Von Hammersmark – “BASTARDOS INGLÓRIOS” ("INGLOURIOUS BASTERDS") (The Weinstein Company/Universal Pictures) MO’NIQUE / Mary - "PRECIOUS: BASED ON THE NOVEL ‘PUSH’ BY SAPPHIRE" (Lionsgate) Melhor elenco AN EDUCATION (Sony Pictures Classics) DOMINIC COOPER / Danny ALFRED MOLINA / Jack CAREY MULLIGAN / Jenny ROSAMUND PIKE / Helen PETER SARSGAARD / David EMMA THOMPSON / Headmistress OLIVIA WILLIAMS / Miss Stubbs THE HURT LOCKER (Summit Entertainment) CHRISTIAN CAMARGO / Col. John Cambridge BRIAN GERAGHTY / Specialist Owen Eldridge EVANGELINE LILLY / Connie James ANTHONY MACKIE / Sgt. -

February 2012

The Park Press Winter Park | Baldwin Park | College Park | M a i t l a n d F E b R u a R y 2 0 1 2 FREE Duck Derby a Makeover Technology Winner allows Creativity 10 15 18 It’s Great To be Grand! – by Tricia Cable Teachers, in general, are some of the the doctor’s visits, helping to pay for med- most thoughtful human beings on the icine, paying for children with impaired planet. They certainly don’t become vision to get glasses, and on occasion, pay- teachers because of the pay, and many of ing their rent to avoid eviction. the professional educators in my circle But the team of five woman who take spend a great deal of their hard-earned on the responsibility to educate the 88 5 wages on classroom supplies and oth- and 6-year-olds who attend kindergarten er items in an effort to be the very best there are not only incredibly dedicated and teachers for our children. John F. Ken- competent, but also a very compassionate nedy once said “Our progress as a nation and caring group. “Students here are such can be no swifter than our progress in sweet and inquisitive boys and girls,” ex- education. The human mind is our fun- plains team leader Sarah Schneider. “They damental resource.” tend to lack the knowledge of the world The kindergarten team at Grand Av- beyond their own neighborhood, and that enue Primary Learning Center takes that Kindergarten Team Leader Sarah Schneider with a group of her is where we come in,” she continues. -

Polish Musicians Merge Art, Business the INAUGURAL EDITION of JAZZ FORUM SHOWCASE POWERED by Szczecin Jazz—Which Ran from Oct

DECEMBER 2019 VOLUME 86 / NUMBER 12 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Andy Hermann, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow; South Africa: Don Albert. -

125Th Street, Harlem, NY

APOLLO ANNUAL REPORT 2016-17th 125 Street, Harlem, NY 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS APOLLO MUSIC APOLLO COMMUNITY LEADERSHIP Page 10 Page 16 Page 4 APOLLO DANCE APOLLO EDUCATION ELLA FITZGERALD Page 12 Page 18 CENTENNIAL CELEBRATION Page 6 APOLLO THEATER APOLLO IN THE MEDIA Page 13 Page 20 WOMEN OF THE WORLD Page 8 APOLLO SIGNATURE APOLLO CELEBRATIONS Page 14 Page 22 APOLLO PEOPLE STATEMENT OF Page 27 OPERATING ACTIVITY Page 24 APOLLO SUPPORTERS Page 28 STATEMENT OF FINANCIAL POSITION Page 26 JOIN THE APOLLO Page 30 “Since its inception, the Apollo Theater has been home to legendary and FROM OUR up-and-coming artists alike, serving as an ever-changing, driving force in popular music and culture, not only in Harlem but across the world.” LEADERSHIP Jonelle Procope, President and CEO of the Apollo Theater We are delighted to share this Annual Report highlighting It is an incredible honor to bring my voice to the Apollo’s the incredible accomplishments of the Apollo’s season. Key storied legacy and exciting future. My first season at the milestones from the 2016-2017 season include welcoming Apollo has been a whirlwind of inspiring and innovative Kamilah Forbes as the new Executive Producer; presenting performances and programs. I especially want to mention The First Noel, the first multi-week run of an Apollo-Presents the four-day Women of the World Festival, which was show on the iconic Mainstage; and welcoming popular anchored by a special tribute concert to the incomparable Brooklyn-based festival, Afropunk, for their first appearance artist/activist Abbey Lincoln. -

New York Women in Film & Television (Nywift)

NEW YORK WOMEN IN FILM & TELEVISION (NYWIFT) TO CELEBRATE EXCEPTIONAL WOMEN AT ST TH THE 41 ANNUAL NYWIFT MUSE AWARDS VIRTUALLY ON THURSDAY, DECEMBER 17 , 2020 GOLDEN GLOBE WINNING ACTRESS AWKWAFINA, TWO TIME GOLDEN GLOBE WINNING ACTRESS RACHEL BROSNAHAN, GRAMMY AWARD WINNING ACTRESS RASHIDA JONES, PULITZER PRIZE WINNING NEW YORK TIMES JOURNALISTS JODI KANTOR & MEGAN TWOHEY, PRESIDENT OF ORION PICTURES ALANA MAYO, AWARD-WINNING DIRECTOR GINA PRINCE-BYTHEWOOD, AND TONY AWARD-WINNING ACTRESS ALI STROKER TO RECEIVE HONORS NEW YORK, NY – NOVEMBER 30, 2020 – New York Women in Film & Television (NYWIFT) is proud to present ST the 41 Annual NYWIFT Muse Awards virtual event on Thursday, December 17, 2020. The event will be held virtually beginning at 1:00 PM ET and available for all those who register to watch on online at nywift.org/muse. This year’s theme is “Art & Advocacy,” as NYWIFT recognizes the role of the creative community in advancing positive social change. CBS Sunday Morning contributor, comedian, actress, and self-described “Accidental Pundette” Nancy Giles will again emcee the afternoon’s event, which celebrates women of outstanding vision and achievement both in front of and behind the camera in film, television, the music industry, and digital media. The honorees for this year’s Muse Awards are some of the most extraordinary women in the business: Awkwafina will receive a “Made in New York” Award from the Mayor’s Office of Media and Entertainment, for her contributions to NYC’s entertainment industry. She is a Golden Globe-winning actress from Queens, New York, who has used her trademark comedic style and signature flair to become a breakout talent. -

CASA Continuing Education Approved Movie List

Movie List for CASA Continuing Education with Optima Categories [Rev. 8/2020] 13 Reasons Why [Optima: Mental Health Issues] [Stars: Dylan Minnette, Katherine Langford, Christian Navarro][ TV Series 49 episodes and counting] Follows teenager Clay Jensen, in his quest to uncover the story behind his classmate and crush, Hannah, and her decision to end her life. [from a Literary Novel see Reading List] A Girl Like Her [Optima: Communicating with Children and Families, Education, Mental Health Issues] [Stars: Lexi Ainsworth, Hunter King, Jimmy Bennett] [1 hr 31 min] Jessica Burns enlists the help of her best friend, Brian, in order to document the relentless harassment she has received from her former friend, Avery Keller, one of South Brookdale High School's most popular students. A Million Little Pieces [Optima: Substance Abuse] [Stars: Aaron Taylor-Johnson, Billy Bob Thornton, Odessa Young] [1 hr 53 minutes] A drug dependent young man faces his past and his inner demons after he is interned in an institution for addicted. An American Crime [Optima: Child Abuse and Neglect] [Stars: Ellen Page, Hayley McFarland, Nick Searcy] [Run time: 1 hr 38 minutes] The true story of suburban housewife Gertrude Baniszewski, who kept a teenage girl locked in the basement of her Indiana home during the 1960s. Antwone Fisher [Optima: Administration of the System, Child Abuse and Neglect, Cultural Competency, Independent Living and Emancipation] [2hr] Antwone Fisher, a young navy man, is forced to see a psychiatrist after a violent outburst against a fellow crewman. During the course of treatment a painful past is revealed and a new hope begins. -

2012 Twenty-Seven Years of Nominees & Winners FILM INDEPENDENT SPIRIT AWARDS

2012 Twenty-Seven Years of Nominees & Winners FILM INDEPENDENT SPIRIT AWARDS BEST FIRST SCREENPLAY 2012 NOMINEES (Winners in bold) *Will Reiser 50/50 BEST FEATURE (Award given to the producer(s)) Mike Cahill & Brit Marling Another Earth *The Artist Thomas Langmann J.C. Chandor Margin Call 50/50 Evan Goldberg, Ben Karlin, Seth Rogen Patrick DeWitt Terri Beginners Miranda de Pencier, Lars Knudsen, Phil Johnston Cedar Rapids Leslie Urdang, Dean Vanech, Jay Van Hoy Drive Michel Litvak, John Palermo, BEST FEMALE LEAD Marc Platt, Gigi Pritzker, Adam Siegel *Michelle Williams My Week with Marilyn Take Shelter Tyler Davidson, Sophia Lin Lauren Ambrose Think of Me The Descendants Jim Burke, Alexander Payne, Jim Taylor Rachael Harris Natural Selection Adepero Oduye Pariah BEST FIRST FEATURE (Award given to the director and producer) Elizabeth Olsen Martha Marcy May Marlene *Margin Call Director: J.C. Chandor Producers: Robert Ogden Barnum, BEST MALE LEAD Michael Benaroya, Neal Dodson, Joe Jenckes, Corey Moosa, Zachary Quinto *Jean Dujardin The Artist Another Earth Director: Mike Cahill Demián Bichir A Better Life Producers: Mike Cahill, Hunter Gray, Brit Marling, Ryan Gosling Drive Nicholas Shumaker Woody Harrelson Rampart In The Family Director: Patrick Wang Michael Shannon Take Shelter Producers: Robert Tonino, Andrew van den Houten, Patrick Wang BEST SUPPORTING FEMALE Martha Marcy May Marlene Director: Sean Durkin Producers: Antonio Campos, Patrick Cunningham, *Shailene Woodley The Descendants Chris Maybach, Josh Mond Jessica Chastain Take Shelter -

35 Years of Nominees and Winners 36

3635 Years of Nominees and Winners 2021 Nominees (Winners in bold) BEST FEATURE JOHN CASSAVETES AWARD BEST MALE LEAD (Award given to the producer) (Award given to the best feature made for under *RIZ AHMED - Sound of Metal $500,000; award given to the writer, director, *NOMADLAND and producer) CHADWICK BOSEMAN - Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom PRODUCERS: Mollye Asher, Dan Janvey, ADARSH GOURAV - The White Tiger Frances McDormand, Peter Spears, Chloé Zhao *RESIDUE WRITER/DIRECTOR: Merawi Gerima ROB MORGAN - Bull FIRST COW PRODUCERS: Neil Kopp, Vincent Savino, THE KILLING OF TWO LOVERS STEVEN YEUN - Minari Anish Savjani WRITER/DIRECTOR/PRODUCER: Robert Machoian PRODUCERS: Scott Christopherson, BEST SUPPORTING FEMALE MA RAINEY’S BLACK BOTTOM Clayne Crawford PRODUCERS: Todd Black, Denzel Washington, *YUH-JUNG YOUN - Minari Dany Wolf LA LEYENDA NEGRA ALEXIS CHIKAEZE - Miss Juneteenth WRITER/DIRECTOR: Patricia Vidal Delgado MINARI YERI HAN - Minari PRODUCERS: Alicia Herder, Marcel Perez PRODUCERS: Dede Gardner, Jeremy Kleiner, VALERIE MAHAFFEY - French Exit Christina Oh LINGUA FRANCA WRITER/DIRECTOR/PRODUCER: Isabel Sandoval TALIA RYDER - Never Rarely Sometimes Always NEVER RARELY SOMETIMES ALWAYS PRODUCERS: Darlene Catly Malimas, Jhett Tolentino, PRODUCERS: Sara Murphy, Adele Romanski Carlo Velayo BEST SUPPORTING MALE BEST FIRST FEATURE SAINT FRANCES *PAUL RACI - Sound of Metal (Award given to the director and producer) DIRECTOR/PRODUCER: Alex Thompson COLMAN DOMINGO - Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom WRITER: Kelly O’Sullivan *SOUND OF METAL ORION LEE - First -

CINE MEJOR ACTOR JEFF BRIDGES / Bad Blake

CINE MEJOR ACTOR JEFF BRIDGES / Bad Blake - "CRAZY HEART" (Fox Searchlight Pictures) GEORGE CLOONEY / Ryan Bingham - "UP IN THE AIR" (Paramount Pictures) COLIN FIRTH / George Falconer - "A SINGLE MAN" (The Weinstein Company) MORGAN FREEMAN / Nelson Mandela - "INVICTUS" (Warner Bros. Pictures) JEREMY RENNER / Staff Sgt. William James - "THE HURT LOCKER" (Summit Entertainment) MEJOR ACTRIZ SANDRA BULLOCK / Leigh Anne Tuohy - "THE BLIND SIDE" (Warner Bros. Pictures) HELEN MIRREN / Sofya - "THE LAST STATION" (Sony Pictures Classics) CAREY MULLIGAN / Jenny - "AN EDUCATION" (Sony Pictures Classics) GABOUREY SIDIBE / Precious - "PRECIOUS: BASED ON THE NOVEL ‘PUSH’ BY SAPPHIRE" (Lionsgate) MERYL STREEP / Julia Child - "JULIE & JULIA" (Columbia Pictures) MEJOR ACTOR DE REPARTO MATT DAMON / Francois Pienaar - "INVICTUS" (Warner Bros. Pictures) WOODY HARRELSON / Captain Tony Stone - "THE MESSENGER" (Oscilloscope Laboratories) CHRISTOPHER PLUMMER / Tolstoy - "THE LAST STATION" (Sony Pictures Classics) STANLEY TUCCI / George Harvey - "THE LOVELY BONES" (Paramount Pictures) CHRISTOPH WALTZ / Col. Hans Landa - "INGLOURIOUS BASTERDS" (The Weinstein Company/Universal Pictures) MEJOR ACTRIZ DE REPARTO PENÉLOPE CRUZ / Carla - "NINE" (The Weinstein Company) VERA FARMIGA / Alex Goran - "UP IN THE AIR" (Paramount Pictures) ANNA KENDRICK / Natalie Keener - "UP IN THE AIR" (Paramount Pictures) DIANE KRUGER / Bridget Von Hammersmark - "INGLOURIOUS BASTERDS" (The Weinstein Company/Universal Pictures) MO’NIQUE / Mary - "PRECIOUS: BASED ON THE NOVEL ‘PUSH’ BY SAPPHIRE" (Lionsgate) MEJOR ELENCO AN EDUCATION (Sony Pictures Classics) DOMINIC COOPER / Danny ALFRED MOLINA / Jack CAREY MULLIGAN / Jenny ROSAMUND PIKE / Helen PETER SARSGAARD / David EMMA THOMPSON / Headmistress OLIVIA WILLIAMS / Miss Stubbs THE HURT LOCKER (Summit Entertainment) CHRISTIAN CAMARGO / Col. John Cambridge BRIAN GERAGHTY / Specialist Owen Eldridge EVANGELINE LILLY / Connie James ANTHONY MACKIE / Sgt. J.T. -

89Th Oscars® Nominations Announced

MEDIA CONTACT Academy Publicity [email protected] January 24, 2017 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Editor’s Note: Nominations press kit and video content available here 89TH OSCARS® NOMINATIONS ANNOUNCED LOS ANGELES, CA — Academy President Cheryl Boone Isaacs, joined by Oscar®-winning and nominated Academy members Demian Bichir, Dustin Lance Black, Glenn Close, Guillermo del Toro, Marcia Gay Harden, Terrence Howard, Jennifer Hudson, Brie Larson, Jason Reitman, Gabourey Sidibe and Ken Watanabe, announced the 89th Academy Awards® nominations today (January 24). This year’s nominations were announced in a pre-taped video package at 5:18 a.m. PT via a global live stream on Oscar.com, Oscars.org and the Academy’s digital platforms; a satellite feed and broadcast media. In keeping with tradition, PwC delivered the Oscars nominations list to the Academy on the evening of January 23. For a complete list of nominees, visit the official Oscars website, www.oscar.com. Academy members from each of the 17 branches vote to determine the nominees in their respective categories – actors nominate actors, film editors nominate film editors, etc. In the Animated Feature Film and Foreign Language Film categories, nominees are selected by a vote of multi-branch screening committees. All voting members are eligible to select the Best Picture nominees. Active members of the Academy are eligible to vote for the winners in all 24 categories beginning Monday, February 13 through Tuesday, February 21. To access the complete nominations press kit, visit www.oscars.org/press/press-kits. The 89th Oscars will be held on Sunday, February 26, 2017, at the Dolby Theatre® at Hollywood & Highland Center® in Hollywood, and will be televised live on the ABC Television Network at 7 p.m. -

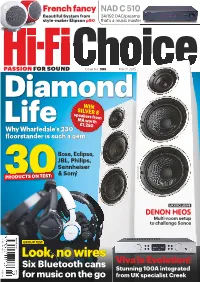

Look, No Wires

French fancy NAD C 510 Beautiful System from 24/192 DAC/preamp style-maker Elipson p90 that’s a music master PASSION FOR SOOUND Issue No. 395 March 2015 Diamond WIN SILVER 8 speakers from MA worth Life £1,250 Why Wharfedale’s 2300 floorstander is such a gem Bose, Eclipse, JBL, Philips, Sennheiser & Sony 30PRODUCTS ON TEST: UK EXCLUSIVE DENON HEOS Multi-room setup to challenge Sonos PRINTED IN THE UK US$13.99 US$13.99 PRINTED IN THE UK £4.50 2015 MARCH GROUP TEST Look, no wires Viva la Evolution! Six Bluetooth cans Stunning 100A integrated for music on the go from UK specialist Creek Our SuperUniti all-in-one player will unleash your digital music, from high- resolution audio files to Spotify playlists. Its analogue heart is an integrated amplifier backed by 40 years of engineering knowledge to offer countless years of musical enjoyment. Just add speakers. SuperUniti. Reference digital music player and integrated amplifier. Next-generation music systems, hand-built in Salisbury, England. Discover more at naimaudio.com INTRODUCTION PASSION FOR SOUND Welcome www.hifichoice.co.uk Issue No. 395 March 2015 Try to imagine for a moment a world without wires connecting your speakers and hi-fi components. It’s a pretty impossible thought for a serious hi-fi fan, right? Most of us see wires like the veins of our hi-fi systems that carry the signal 58 Novafidelity X12 between vital components enabling the music to flow to our speakers, delivering soundwaves to ears, bringing the music to life and feeding our souls. -

Obama Signs LGBT Hospital Access Memo President Calls Lesbian Denied Access to Partner Page 8 by Tracy Baim

THE VOICE OF CHICAGO’S GAY, LESBIAN, BI AND TRANS COMMUNITY SINCE 1985 April 21, 2010 • vol 25 no 29 www.WindyCityMediaGroup.com Gender JUST rally Obama signs LGBT hospital access memo President calls lesbian denied access to partner page 8 BY TRacY Baim “I’m sorry.” Those two little words are what Janice Lang- behn has been waiting to hear since February 2007, when her partner of 18 years, Lisa Pond, just 39 years old, died separated from Langbehn and their children. But the apology did not come from Jack- son Memorial Hospital in Florida, where Pond lay dying from a brain aneurysm suffered Feb. 18, 2007, hours after the family boarded the R Family Cruise. Instead, President Barack Obama said those words to Langbehn in a phone call April 15, 2010, when he phoned her in Olym- pia, Wash., from Air Force One, ironically while it circled over Miami, where Jackson Memorial is Chicago located. Obama called Langbehn to explain a memo he Red Stars page 22 had signed that day to address discrimination LGBT families face from healthcare facilities. The Obama memo directs the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS), Kathleen Sebelius, to move forward on steps to address hospital visitation and other related LGBT healthcare access issues. The resulting regula- tion is expected to require hospitals that receive Turn to page 6 Janice Langbehn (left) and Lisa Pond in 1996. Dan Choi sounds off at Boston gala BY CHUCK COLBERT What should the president do? Choi insists that the president include repeal language in the Mario In the nearly six weeks since his arrest for civil Defense Authorization Act of 2010.