Reality Television Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} My Life Is a Toilet by Gretel Killeen

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} My Life is a Toilet by Gretel Killeen Killeen, Gretel 1963- Born 1963, in Turramurra, New South Wales, Australia; children: Zeke Morgan, Eppie Morgan. ADDRESSES: CAREER: Freelance writer. Worked as standup comedian, actress, singer, broadcast journalist and presenter, theatrical producer, and advertising copywriter. 9 Network, Sydney, Australia, reporter and writer for Midday Show for seven years; host of the Australian broadcast of the reality program Big Brother, 2003-06; guest on television programs related to the Big Brother series and to other Australian radio and television programs. Appeared as Rhonda Halliwell in the film Gettin' Square, 2003. UNICEF, Australian ambassador, 2001. AWARDS, HONORS: Penguin Award, 1989, for writing and performing "Oz Rap"; Mo Award, best female comic, 2001. WRITINGS: Baby on Board: A Beginner's Guide to Pregnancy, Mandarin (Port Melbourne, Victoria, Australia), 1991. How to Live with a Sausage in a Bonnet, illustrated by Craig Smith, Random House Australia (Milsons Point, New South Wales, Australia), 1991. The Every Girl's Geek Guide, Random House Australia (Milsons Point, New South Wales, Australia), 1992. My Life Is a Toilet, Random House Australia (Milsons Point, New South Wales, Australia), 1994. The My Life Is a Toilet Instruction Book: How to Make the Most of Your Pathetic Existence, Random House Australia (Milsons Point, New South Wales, Australia), 1995. My Sister's a Yo-yo, Random House Australia (Milsons Point, New South Wales, Australia), 1997, new edition, illustrated by Leigh Hobbs, Red Fox (London, England), 2002. My Sister's an Alien, illustrated by Leigh Hobbs, Red Fox (Milsons Point, New South Wales, Australia), 1998. -

1 Boston Legal the New Kids on the Block Season 3, Episode 2 Written

Boston Legal The New Kids on the Block Season 3, Episode 2 Written by David E. Kelley © 2006 David E. Kelley Productions. All Rights Reserved Airdate: September 26, 2006 Transcribed by Sheri and Imamess for boston-legal.org [version updated October 7, 2006] Elevator interior: Crane, Poole & Schmidt Claire Simms: This is abusive. Making me leave New York? I’m gonna call my parents and tell them I’m being abused. Jeffrey Coho: I promise you’ll be happy. It’s the best firm in Boston. Elevator dings as they arrive at their floor. Claire Simms: Ugh. Reception Area: Crane, Poole & Schmidt Denny Crane: cigar in mouth, talking to administrative assistant Write down your phone number. Claire Simms: I don’t like it. Denny Crane: Well, well, well, well, well. If you’re a client, I’ll get you off. If you’re not, the offer’s still good. Claire Simms: Okay. Ick and double ick. Jeffrey Coho: We’re the new guys. Denny Crane: Oh, please. If there were new guys, they would’ve shown up at the season premiere. Claire Simms: He’s smoking, for God’s sake. Denny Crane: It’s a personal gift from Bill Clinton. If you only knew where this cigar has been. Claire Simms: Okay, he’s officially the grossest person I’ve ever met. Jeffrey Coho: See that sign that says, “Crane, Poole & Schmidt”? Denny Crane: pointing to himself with his cigar Crane. Welcome to Boston Legal. Claire Simms: Jeffrey. The gross man is fondling me. Denny Crane: It’s the official firm greeting. -

Index to Marrickville Heritage Society Inc Newsletter Issn 0818-0695

INDEX TO MARRICKVILLE HERITAGE SOCIETY INC NEWSLETTER ISSN 0818-0695 Vol 1 No 1 June 1984 To Vol 25 No 10 June 2009 Compiled by Robert Thompson The first issue of Marrickville Heritage Society’s Newsletter appeared in June 1984, just a short time after the formation of the Society. That first issue boldly declared itself to be vol 1 no 1. That we are now able to present an index to Volumes 1 to 25 is due to the determination and skill of each of the editors and contributors who have continued to produce a publication of such high quality. An early decision taken by members of the Society was that it should be an active organisation, rather than a remote one where members would simply pay their subscriptions and leave all the work to a committee. Because of its superb program of activities it has become a true ‘society’. The resulting comradeship has seen members working together to preserve not only the built environment of Marrickville but, perhaps more importantly, our social history as well. The story of Marrickville’s people is a vibrant, ongoing one in which each of us continues to play a part. And while members’ research will uncover and document more of our past, the initiatives and activities of Marrickville Heritage Society will ensure its relevance to a wider society, encouraging the protection of our heritage into the future. The Newsletter records each of our excursions and the speakers – from within and outside the Society – who have entertained and informed us; the fascinating, the horrifying and the sometimes bizarre in Marrickville’s unique story. -

("Conditions of Entry") Schedule Promotion: the Block Promoter: Nine Network Australia Pty Ltd ABN 88 008 685 407, 24 Artarmon Road, Willoughby, NSW 2068, Australia

NBN The Block Competition Terms & Conditions ("Conditions of Entry") Schedule Promotion: The Block Promoter: Nine Network Australia Pty Ltd ABN 88 008 685 407, 24 Artarmon Road, Willoughby, NSW 2068, Australia. Ph: (02) 9906 9999 Promotional Period: Start date: 09/10/16 at 09:00 am AEDT End date: 19/10/16 at 12:00 pm AEDT Eligible entrants: Entry is only open to residents of NSW and QLD only who are available to travel to Melbourne between 29/10/16 and 30/10/16. How to Enter: To enter the Promotion, the entrant must complete the following steps during the Promotional Period: (a) visit www.nbntv.com.au; (b) follow the prompts to the Promotion tab; (c) input the requested details in the Promotion entry form including their full name, address, daytime contact phone number, email address and code word (d) submit the fully completed entry form. Entries permitted: Entrants may enter multiple times provided each entry is submitted separately in accordance with the entry instructions above. The entrant is eligible to win a maximum of one (1) prize only. By completing the entry method, the entrant will receive one (1) entry. Total Prize Pool: $2062.00 Prize Description Number of Value (per prize) Winning Method this prize The prize is a trip for two (2) adults to Melbourne between 1 Up to Draw date: 29/10/2016 – 30/10/2016 and includes the following: AUD$2062.00 20/10/16 at 10:00 1 night standard twin share accommodation in am AEDT Melbourne (min 3.5 star) (conditions apply); return economy class flights for 2 adults from either Gold Coast or Newcastle to Melbourne); a guided tour of The Block apartments return airport and hotel transfers in Melbourne Prize Conditions: No part of the prize is exchangeable, redeemable or transferable. -

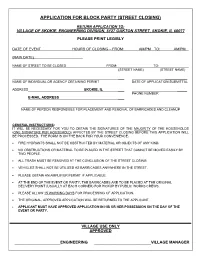

Application for Block Party (Street Closing)

APPLICATION FOR BLOCK PARTY (STREET CLOSING) RETURN APPLICATION TO: VILLAGE OF SKOKIE, ENGINEERING DIVISION, 5127 OAKTON STREET, SKOKIE, IL 60077 PLEASE PRINT LEGIBLY DATE OF EVENT HOURS OF CLOSING – FROM: AM/PM TO: AM/PM (RAIN DATE) NAME OF STREET TO BE CLOSED FROM: TO: (STREET NAME) (STREET NAME) ___ ___________ NAME OF INDIVIDUAL OR AGENCY OBTAINING PERMIT DATE OF APPLICATION SUBMITTAL ADDRESS SKOKIE, IL ___ _____ PHONE NUMBER E-MAIL ADDRESS ___ _______________________________________________________________________________ NAME OF PERSON RESPONSIBLE FOR PLACEMENT AND REMOVAL OF BARRICADES AND CLEANUP GENERAL INSTRUCTIONS: IT WILL BE NECESSARY FOR YOU TO OBTAIN THE SIGNATURES OF THE MAJORITY OF THE HOUSEHOLDS (ONE SIGNATURE PER HOUSEHOLD) AFFECTED BY THE STREET CLOSING BEFORE THIS APPLICATION WILL BE PROCESSED. THE FORM IS ON THE BACK FOR YOUR CONVENIENCE. FIRE HYDRANTS SHALL NOT BE OBSTRUCTED BY MATERIAL OR OBJECTS OF ANY KIND. NO OBSTRUCTIONS OR MATERIAL TO BE PLACED IN THE STREET THAT CANNOT BE MOVED EASILY BY TWO PEOPLE. ALL TRASH MUST BE REMOVED AT THE CONCLUSION OF THE STREET CLOSING. VEHICLES SHALL NOT BE UTILIZED AS BARRICADES ANYWHERE IN THE STREET. PLEASE OBTAIN AN AMPLIFIER PERMIT IF APPLICABLE. AT THE END OF THE EVENT OR PARTY, THE BARRICADES ARE TO BE PLACED AT THE ORIGINAL DELIVERY POINT (USUALLY AT EACH CORNER) FOR PICKUP BY PUBLIC WORKS CREWS. PLEASE ALLOW 15 WORKING DAYS FOR PROCESSING OF APPLICATION. THE ORIGINAL, APPROVED APPLICATION WILL BE RETURNED TO THE APPLICANT. APPLICANT MUST HAVE APPROVED APPLICATION IN HIS OR HER POSSESSION ON THE DAY OF THE EVENT OR PARTY. VILLAGE USE ONLY APPROVED _____________________ENGINEERING __________________________VILLAGE MANAGER A MAJORITY OF HOUSEHOLDS AFFECTED BY THE STREET CLOSING MUST SIGN. -

Nine Wins All Key Demos for 2019

NINE WINS ALL KEY DEMOS FOR 2019 • No. 1 Network All Key Demographics • No. 1 Network Total People • No. 1 Primary Channel All Key Demographics and Total People • No. 1 Commercial Free-to-air BVOD: 9Now • No. 1 Overall Program: State of Origin Game 1 • No. 1 Overall Regular Program: Married at First Sight • No. 1 New Program: LEGO Masters • No. 1 & No. 2 Reality Series: Married at First Sight & The Block • No. 1 & No. 2 & No. 3 Light Entertainment Series: Lego Masters, Australian Ninja Warrior & The Voice • No. 1 Comedy Program: Hamish & Andy’s “Perfect” Holiday • No. 1 Sports Program: State of Origin • No. 1 Weekly Public Affairs Program: 60 Minutes • No. 1 Daily Public Affairs Program: A Current Affair • No. 1 Multichannel Program: The Ashes (4th Test, Day 5, Session 1) With the official ratings survey period wrapping up overnight, Nine is celebrating its best ratings share performance of all time. Key to the network’s success is a year-round schedule of premium Australian content that has once again delivered proven consistency of audience across all advertiser-preferred demographics. It is this reliable slate of family-friendly programming that sees Nine crowned Australia’s No. 1 network for 2019 with the demographics most highly sought after – People 25-54, People 16-39 and Grocery Shoppers with Children. Nine’s primary channel also ranks as Australia’s most watched channel in 2019 with all key demographics. Furthermore, Nine also secured the greatest number of viewers (Total People) for both its primary channel and network share. Nine can also lay claim to the highest rating program of the year, with the first State of Origin game between NSW and Queensland securing a national linear broadcast average audience of 3.230 million viewers (Metro: 2.192 million/Regional: 1.038 million). -

The Block Magazine the Block Is Back in 2020

THE BLOCK MAGAZINE THE BLOCK IS BACK IN 2020 Season 16 of The Block maybe the biggest and most difficult series of The Block yet! The Blockheads will transform five existing homes that have been relocated from different eras dating from 1910 to 1950. The challenge for each team will be to modernise whilst maintaining a nod to heritage in their styles. We’ll capture it all in the 2020 edition of The Block magazine and on our dedicated The Block section of Homes to Love. THE BLOCK 2020 magazine will provide the final reveals, home by home and room by ON SALE, SPECS room featuring all the details. We’ll cover floor plans, before and after shots and budget recommendations, plus the ‘Little Block Book’ of products and suppliers including & RATES furniture, home-wares, prices, stockists, paint colour, lighting, flooring, tiles and surfaces, ON SALE: 16 Nov, 2020 joinery and fittings – everything you need to know to recreate 2020’s sensational BOOKING: 23 Oct, 2020 makeovers. MATERIAL: 27 Nov, 2020 THE BLOCK 2019 series was an outstanding success with the average episode attracting DIMENSIONS just under a million viewers and the finale being the highest rating episode for the season BOOK SIZE: 270x225mm with 1.9M+ Australians tuning in to see Tess & Luke take out the top spot. PRINT RUN: 40,000 Don’t miss out! Be part of Australia’s favourite home renovation show with THE BLOCK ADVERTISING RATES 2020 magazine, flying off the shelves in November 2020. – and HOMES TO LOVE, going DPS: $12,000 live in August 2020 (exact time tbc). -

Measure Twice Cut Once AUGUST 2017 the Builder’S Guide to All Things Timber and Hardware

Measure Twice Cut Once AUGUST 2017 The builder’s guide to all things timber and hardware. Getting To Know You: In This Issue Jeff Hitchcock. • Things Need To Know About Jeff Hitchcock Jeff is one of our drivers here at she was six. I’d like to see where Wilson Timbers. We see Jeff regularly, she came from and meet the • A Field Report From The Boral when he pulls up with an empty truck family that stayed behind.” gets the next delivery loaded and ties I want to head to America get and Bostick’s Trade Night it down properly, (see p3 for how he myself a mustang – cos I’ve doesn’t do it). Then he’s back off on always wanted one since I was a • A Breakthrough In Level the road again. kid… then drive it the length of Foundations route 66.” We caught up with Jeff for a quick Q and A. 6. Where do you see yourself in 10 • Our Responsibility To The years? “Retired. I’m 57, I figure I’ll Planet 1. How long have you worked at retire in 10 years’ time. So 3,627 WT’s for? I’ve been driving here days to go…” for 13 years after stints as a tow truck driver and a taxi driver. 7. What’s the dumbest thing you’ve done that actually turned out 2. If you won a cool million dollars, pretty well?“Getting married. what is the first thing you would Valerie and I have we’ve been buy/do? “Pay off all my debts and married for 21 years now. -

The Good News December 2019

THE GOOD NEWS DECEMBER 2019 Dear Parents, I hope your Thanksgiving was filled with fun, food, family, and friends! We began our day with a wonderful parish Thanksgiving Mass! Thank you so much to our wonderful Religious Education Students who participated as Readers, Greeters, Altar Preparers, Gift Presenters and Altar Servers: Sigmmond & Nash Antony, Alfina, Penelope, Zarina and Zeke Eull, Ashelyn Tablan, Michael and David Solimondo, Anthony La Firenza, Devyn Rochford, Caitlyn Nicole & Kian Wong, Mary Soto, Brenna Bitcon, Gabby Baluyot, Christopher Foes, Isabella Schwartz, Ariana Henderson, Dean & Nathan Staso, Patrick Babuder, and Anthony and Raymond Biedenbeder. Also, special thanks to our teachers: Barbara Mullen, Jeannie Haworth, Barbara Molina, Robyn Solimando, Yoli Baluyot and Caroline Anthony for all their help at the practice and Mass. We turn the corner and the Advent/Christmas Season is upon us…… Back by popular demand this year! Last week I sent home, with the oldest child, a Liturgical Calendar for each family. It is identical to the ones that are used in the classroom with the children. You will notice that this is no ordinary calendar. It is not organized by months and weeks and days. Instead, it is a circle of Sundays, seasons, and feasts. Each Sunday is represented by a block that is the color of the liturgical season in which the Sunday falls. Noted in the block is the Gospel reading for that Sunday. On the back side of the calendar is some information about St. Matthew. There are many ways to use the calendar during the year, some suggestions are in the Family Guide. -

Vince Valitutti

VINCE VALITUTTI IMDB http://imdb.com/name/nm1599631/ PO Box 756 Main Beach~Gold Coast~Qld 4217~ Australia Aust +61 414 069 917 vincevalitutti.com [email protected] FILM AND TELEVISION 2013 Camp Client: NBC Television Directors: Lynn-Maree Danzey, Shawn Seet, Ben Chessell Cast: Rachael Griffiths, Jack Thompson, Nikolai Niolaeff, Tom Green, Adam Garcia 2013 72hrs: Client: TNT Network Director: Neil Degroot Host: R. Brandon Johnson 2013 Nim’s Island 2: Client: Fox-Walden Director: Brendan Maher Cast: Bindi Irwin, Matthew Lillard, John Waters, Sebastian Gregory, Toby Wallace 2013 Fatal Honeymoon: Client: Lifetime Television Director: Nadia Tass Cast: Harvey Keitel, Billy Miller, Gary Sweet, Amber Clayton 2013 Secret of Mako Island: Client: Johnathon Shiff productions Directors: Grant Brown, Evan Clarry Cast: Lucy Fry, Ivy Latimer, Amy Ruffle, Kerith Atkinson, Gemma Forsyth 2013 Reef Doctors: Client: Johnathon Shiff productions, Network 10 Directors: Grant Brown, Colin Budds Cast: Lisa McCune, Matt Day, Andrew Ryan, Richard Brancatisano, Susan Hoecke 2012 Absolute Deception: Client: Limelight International Director: Brian Trenchard-Smith Cast: Cuba Gooding Jr, Emmanuelle Vaugier, Evert McQueen, Brad McMurray 2012 The Strange Calls: Client: Hoodlum Entertainment Director: Daley Pearson Cast: Barry Crocker, Toby Truslove, Patrick Brammall, Katherine Hicks 2011 Slide: Client: Foxtel, Fremantle Media Director: Shawn Seet, Garth Maxwell, Tori Garrett Cast: Lincoln Lewis, Emily Robins, Ben Schumann, Brenton Thwaites, Gracie Gilbert -

Gretel Killeen

Gretel Killeen Broadcaster, author, MC & host Gretel Killeen is known as a stand-up comic, one of Australia’s top advertising voice-artists, a radio host and host of one of the nation’s most controversial reality TV shows, Big Brother. She is also a best-selling author, a journalist, humorist, film director, documentary maker, travel writer – and live performer in the war zones of Afghanistan and Iraq. Gretel Killeen’s career began shortly after she dropped out of law studies at university and accidentally performed stand-up comedy at a poetry reading. This led to comedy writing for Australian radio station 2JJJ and regular spots on national television as a humorist, commentator and actor. Since then she has worked continuously, making Australian audiences laugh. With her well-known warmth, wisdom and wicked wit, Gretel Killeen is the perfect MC or host for an awards night or corporate event. Gretel Killeen has written more than twenty books, including the My Sister Series, My Life is a Toilet and My Life is a Wedgie for younger readers, the teen romance, I Love You Zelda Bloo, and the hilarious memoire, The Night My Bum Dropped, for adults. Gretel has also written for many of Australia’s leading publications, was a regular columnist with The Australian newspaper’s magazine and a weekly columnist with The Sun Herald. While a Goodwill Ambassador for UNICEF Gretel wrote and directed TV commercials for unexploded ordnance awareness in Laos and the need for financial aid in Bangladesh, and wrote and directed a documentary on AIDS Orphans in Zambia. -

Criminal Liability for Maritime Disasters Causing Death in Australian Territorial Waters

YOU’RE A CROOK, CAPTAIN HOOK: CRIMINAL LIABILITY FOR MARITIME DISASTERS CAUSING DEATH IN AUSTRALIAN TERRITORIAL WATERS ALEXANDER M MCVEY This thesis is presented for the Honours degree of Bachelor of Laws of Murdoch University. The author hereby declares that it is his own account of his research. 15,149 words (excluding title pages, table of contents, footnotes and bibliography) 2015 To Linda, who encouraged my curious mind, and to Matt and Leanne who still do. I am truly grateful to my supervisor, Dr Kate Lewins, for her guidance and support. ABSTRACT The world is seeing more maritime disasters every year, in a variety of jurisdictions around the world. Many of these disasters cause a large number of deaths. As a result of those deaths, there is often pressure on the relevant authorities to prosecute the parties responsible. The master of the vessel may be the most obvious party to charge, but there may have been other parties responsible for the operation and management of the vessel whose negligent or reckless conduct contributed to the vessel’s demise. Despite the contributions of other parties, the master of a vessel may become a scapegoat, and, as a result, bear the brunt of any prosecution. There are several reasons why the master may receive the most blame in these situations. One of those may be that the law in force within the relevant jurisdiction does not provide particular criminal charges that apply to parties other than the master. This paper asks whether Australian law encourages prosecuting bodies to scapegoat the master of a vessel and whether this is demonstrative of the wider problem of seafarer criminalisation worldwide.