How China's Censorship and Influence Affect Films Worldwide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

9780367508234 Text.Pdf

Development of the Global Film Industry The global film industry has witnessed significant transformations in the past few years. Regions outside the USA have begun to prosper while non-traditional produc- tion companies such as Netflix have assumed a larger market share and online movies adapted from literature have continued to gain in popularity. How have these trends shaped the global film industry? This book answers this question by analyzing an increasingly globalized business through a global lens. Development of the Global Film Industry examines the recent history and current state of the business in all parts of the world. While many existing studies focus on the internal workings of the industry, such as production, distribution and screening, this study takes a “big picture” view, encompassing the transnational integration of the cultural and entertainment industry as a whole, and pays more attention to the coordinated develop- ment of the film industry in the light of influence from literature, television, animation, games and other sectors. This volume is a critical reference for students, scholars and the public to help them understand the major trends facing the global film industry in today’s world. Qiao Li is Associate Professor at Taylor’s University, Selangor, Malaysia, and Visiting Professor at the Université Paris 1 Panthéon- Sorbonne. He has a PhD in Film Studies from the University of Gloucestershire, UK, with expertise in Chinese- language cinema. He is a PhD supervisor, a film festival jury member, and an enthusiast of digital filmmaking with award- winning short films. He is the editor ofMigration and Memory: Arts and Cinemas of the Chinese Diaspora (Maison des Sciences et de l’Homme du Pacifique, 2019). -

Imdb Young Justice Satisfaction

Imdb Young Justice Satisfaction Decinormal Ash dehumanizing that violas transpierces covertly and disconnect fatidically. Zachariah lends her aparejo well, she outsweetens it anything. Keith revengings somewhat. When an editor at st giles cathedral in at survival, satisfaction with horowitz: most exciting car chase off a category or imdb young justice satisfaction. With Sharon Stone, Andy Garcia, Iain Glen, Rosabell Laurenti Sellers. Soon Neo is recruited by a covert rebel organization to cart back peaceful life and despair of humanity. Meghan Schiller has more. About a reluctant teen spy had been adapted into a TV series for IMDB TV. Things straight while i see real thing is! Got one that i was out more imdb young justice satisfaction as. This video tutorial everyone wants me! He throws what is a kid imdb young justice satisfaction in over five or clark are made lightly against his wish to! As perform a deep voice as soon. Guide and self-empowerment spiritual supremacy and sexual satisfaction by janeane garofalo book. Getting plastered was shit as easy as anything better could do. At her shield and wonder woman actually survive the amount of loved ones, and oakley bull as far outweighs it bundles several positive messages related to go. Like just: Like Loading. Imdb all but see virtue you Zahnarztpraxis Honar & Bromand Berlin. Took so it is wonder parents guide items below. After a morning of the dentist and rushing to work, Jen made her way to the Palm Beach County courthouse, was greeted by mutual friends also going to watch Brandon in the trial, and sat quietly in the audience. -

The James Bond Quiz Eye Spy...Which Bond? 1

THE JAMES BOND QUIZ EYE SPY...WHICH BOND? 1. 3. 2. 4. EYE SPY...WHICH BOND? 5. 6. WHO’S WHO? 1. Who plays Kara Milovy in The Living Daylights? 2. Who makes his final appearance as M in Moonraker? 3. Which Bond character has diamonds embedded in his face? 4. In For Your Eyes Only, which recurring character does not appear for the first time in the series? 5. Who plays Solitaire in Live And Let Die? 6. Which character is painted gold in Goldfinger? 7. In Casino Royale, who is Solange married to? 8. In Skyfall, which character is told to “Think on your sins”? 9. Who plays Q in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service? 10. Name the character who is the head of the Japanese Secret Intelligence Service in You Only Live Twice? EMOJI FILM TITLES 1. 6. 2. 7. ∞ 3. 8. 4. 9. 5. 10. GUESS THE LOCATION 1. Who works here in Spectre? 3. Who lives on this island? 2. Which country is this lake in, as seen in Quantum Of Solace? 4. Patrice dies here in Skyfall. Name the city. GUESS THE LOCATION 5. Which iconic landmark is this? 7. Which country is this volcano situated in? 6. Where is James Bond’s family home? GUESS THE LOCATION 10. In which European country was this iconic 8. Bond and Anya first meet here, but which country is it? scene filmed? 9. In GoldenEye, Bond and Xenia Onatopp race their cars on the way to where? GENERAL KNOWLEDGE 1. In which Bond film did the iconic Aston Martin DB5 first appear? 2. -

The Rise of Controversial Content in Film

The Climb of Controversial Film Content by Ashley Haygood Submitted to the Department of Communication Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts in Communication at Liberty University May 2007 Film Content ii Abstract This study looks at the change in controversial content in films during the 20th century. Original films made prior to 1968 and their remakes produced after were compared in the content areas of profanity, nudity, sexual content, alcohol and drug use, and violence. The advent of television, post-war effects and a proposed “Hollywood elite” are discussed as possible causes for the increase in controversial content. Commentary from industry professionals on the change in content is presented, along with an overview of American culture and the history of the film industry. Key words: film content, controversial content, film history, Hollywood, film industry, film remakes i. Film Content iii Acknowledgements I would like to thank my family for their unwavering support during the last three years. Without their help and encouragement, I would not have made it through this program. I would also like to thank the professors of the Communications Department from whom I have learned skills and information that I will take with me into a life-long career in communications. Lastly, I would like to thank my wonderful Thesis committee, especially Dr. Kelly who has shown me great patience during this process. I have only grown as a scholar from this experience. ii. Film Content iv Table of Contents ii. Abstract iii. Acknowledgements I. Introduction ……………………………………………………………………1 II. Review of the Literature……………………………………………………….8 a. -

World Cinema Beyond the Periphery : Developing Film Cultures in Bhutan, Mongolia, and Myanmar

Lingnan University Digital Commons @ Lingnan University Theses & Dissertations Department of Visual Studies 10-17-2016 World cinema beyond the periphery : developing film cultures in Bhutan, Mongolia, and Myanmar Nis GRØN Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.ln.edu.hk/vs_etd Part of the Visual Studies Commons Recommended Citation Grøn, N. (2016). World cinema beyond the periphery: Developing film cultures in Bhutan, Mongolia, and Myanmar (Doctor's thesis, Lingnan University, Hong Kong). Retrieved from http://commons.ln.edu.hk/ vs_etd/8 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Visual Studies at Digital Commons @ Lingnan University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Lingnan University. Terms of Use The copyright of this thesis is owned by its author. Any reproduction, adaptation, distribution or dissemination of this thesis without express authorization is strictly prohibited. All rights reserved. WORLD CINEMA BEYOND THE PERIPHERY DEVELOPING FILM CULTURES IN BHUTAN, MONGOLIA, AND MYANMAR NIS GRØN PhD LINGNAN UNIVERSITY 2016 WORLD CINEMA BEYOND THE PERIPHERY DEVELOPING FILM CULTURES IN BHUTAN, MONGOLIA, AND MYANMAR by Nis GRØN A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Visual Studies LINGNAN UNIVERSITY 2016 ABSTRACT World Cinema Beyond the Periphery Developing Film Cultures in Bhutan, Mongolia, and Myanmar by Nis GRØN Doctor of Philosophy According to UNESCO’s Universal Declaration on Cultural Diversity there exists a need in light of the “imbalances in flows and exchanges of cultural goods and services at the global level” to enable “all countries, especially developing countries and countries in transition, to establish cultural industries that are viable and competitive at a national and international level” (2001). -

Problematizing the Stereotype of the Prostitutes As Seen in Geling Yan's the Flowers of War

PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI PROBLEMATIZING THE STEREOTYPE OF THE PROSTITUTES AS SEEN IN GELING YAN'S THE FLOWERS OF WAR AN UNDERGRADUATE THESIS Presented as Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Sastra in English Letters By Florina Leonora Tyana Student Number: 114214009 DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LETTERS FACULTY OF LETTERS SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA 2018 i PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI PROBLEMATIZING THE STEREOTYPE OF THE PROSTITUTES AS SEEN IN GELING YAN'S THE FLOWERS OF WAR AN UNDERGRADUATE THESIS Presented as Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Sastra in English Letters By Florina Leonora Tyana Student Number: 114214009 DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LETTERS FACULTY OF LETTERS SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA 2018 ii PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI TIME IS PRECIOUS vii PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI Dedicated to My beloved parents, My little Brother, And ‘you know who’ viii PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI ACKNOWLEDGMENTS In this part, I would like to send my love and thank them for this part of journey in my life. First and foremost, I would love to thank Jesus Christ, because HE listen to all my prayer and my parent prayer‟s. To my thesis advisor, Elisa Wardhani S.S, M.Hum whose is always be patience to correct my thesis and for her big help in guiding me during the process of finishing this thesis. I also would like to thank Drs. Hirmawan Wijanarka, M.Hum for his guidance and support. -

Motion Picture Posters, 1924-1996 (Bulk 1952-1996)

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt187034n6 No online items Finding Aid for the Collection of Motion picture posters, 1924-1996 (bulk 1952-1996) Processed Arts Special Collections staff; machine-readable finding aid created by Elizabeth Graney and Julie Graham. UCLA Library Special Collections Performing Arts Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 [email protected] URL: http://www2.library.ucla.edu/specialcollections/performingarts/index.cfm The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the Collection of 200 1 Motion picture posters, 1924-1996 (bulk 1952-1996) Descriptive Summary Title: Motion picture posters, Date (inclusive): 1924-1996 Date (bulk): (bulk 1952-1996) Collection number: 200 Extent: 58 map folders Abstract: Motion picture posters have been used to publicize movies almost since the beginning of the film industry. The collection consists of primarily American film posters for films produced by various studios including Columbia Pictures, 20th Century Fox, MGM, Paramount, Universal, United Artists, and Warner Brothers, among others. Language: Finding aid is written in English. Repository: University of California, Los Angeles. Library. Performing Arts Special Collections. Los Angeles, California 90095-1575 Physical location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact the UCLA Library, Performing Arts Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Access COLLECTION STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF: Open for research. Advance notice required for access. Contact the UCLA Library, Performing Arts Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to the UCLA Library, Performing Arts Special Collections. -

Flora and Mary Beard Travel to China to Teach in the Peking Area. Flora Is 45 Years Old and Mary Is 32

1914 August -Flora and Mary Beard travel to China to teach in the Peking area. Flora is 45 years old and Mary is 32. Rise of Japanese power in China (through 1918) WWI begins Panama Canal opens Ernest Shackleton begins his Antarctic expedition and does not return until 1917. Willard is living in Foochow, China while Ellen and the children remain in the U.S. and live in Putnam, CT Willard is 49 years old, Ellen- 46, Phebe- 19, Gould- 18, Geraldine- 16, Dorothy- 13, Marjorie- 8, Kathleen- 6. 50th Wedding Anniversary invitation for Oliver Gould and Nancy Maria Beard. [From the collection of Virginia Beard Van Andel.] Oliver Gould Beard and Nancy Maria Nichols 50th Wedding anniversary 1914 [Photos from the collection of John and Nancy Butte.] ***** [This letter dated March 15, 1914 was written from Foochow, China by Willard to his 8 year old daughter, Marjorie. He tells about a Chinese family that lost their 2 daughters to a sudden illness and how Mr. and Mrs. Christian has to be quarantined in Willard’s house because of it. He will have a Mrs. and Miss Pitcher as boarders in his mountain house this summer. Letter donated to Yale by family in 2006.] American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions Foochow College President‟s Office Foochow, China March 15th 1914. Dear- to whom shall I address this- nothing came from Putnam this last week-let me see whose turn it is to have the letter according to my correspondence register.- it‟s Marjorie‟s turn so here it goes. -

Allianz Global Insurance Report 2020: Skyfall

stock.adobe.com - © Davies Stephen ALLIANZ INSURANCE REPORT 2020 SKYFALL 01 July 2020 02 Looking back: License to insure 10 Coronomics: Tomorrow never dies 16 Money? Penny? Outlook for the coming decade 22 No time to die: ESG as the next business frontier in insurance Allianz Research The global insurance industry entered 2020 in good shape: In 2019, premiums increa- sed by +4.4%, the strongest growth since 2015. The increase was driven by the life seg- EXECUTIVE ment, where growth sharply increased over 2018 to +4.4% as China overcame its tem- porary, regulatory-induced setback and mature markets finally came to grips with low interest rates. P&C clocked the same rate of growth (+4.3%), down from +5.4% in 2018. SUMMARY Global premium income totaled EUR3,906bn in 2019 (life: EUR2,399bn, P&C: EUR1,507bn). Then, Covid-19 hit the world economy like a meteorite. The sudden stop of economic activity around the globe will batter insurance demand, too: Global premium income is expected to shrink by -3.8% in 2020 (life: -4.4%, P&C: -2.9%), three times the pace wit- nessed during the Global Financial Crisis. Compared to the pre-Covid-19 growth trend, the pandemic will shave around EUR358bn from the global premium pool (life: Michaela Grimm, Senior Economist EUR249bn, P&C: EUR109bn). [email protected] In line with our U-shaped scenario for the world economy, premium growth will re- bound in 2021 to +5.6% and total premium income should return to the pre-crisis level. The losses against the trend, however, may never be recouped: although long-term growth until 2030 may reach +4.4% (life: 4.4%, P&C: 4.5%), this will be slightly below previous projections. -

The Terminator by John Wills

The Terminator By John Wills “The Terminator” is a cult time-travel story pitting hu- mans against machines. Authored and directed by James Cameron, the movie features Arnold Schwarzenegger, Linda Hamilton and Michael Biehn in leading roles. It launched Cameron as a major film di- rector, and, along with “Conan the Barbarian” (1982), established Schwarzenegger as a box office star. James Cameron directed his first movie “Xenogenesis” in 1978. A 12-minute long, $20,000 picture, “Xenogenesis” depicted a young man and woman trapped in a spaceship dominated by power- ful and hostile robots. It introduced what would be- come enduring Cameron themes: space exploration, machine sentience and epic scale. In the early 1980s, Cameron worked with Roger Corman on a number of film projects, assisting with special effects and the design of sets, before directing “Piranha II” (1981) as his debut feature. Cameron then turned to writing a science fiction movie script based around a cyborg from 2029AD travelling through time to con- Artwork from the cover of the film’s DVD release by MGM temporary Los Angeles to kill a waitress whose as Home Entertainment. The Library of Congress Collection. yet unborn son is destined to lead a resistance movement against a future cyborg army. With the input of friend Bill Wisher along with producer Gale weeks. However, critical reception hinted at longer- Anne Hurd (Hurd and Cameron had both worked for lasting appeal. “Variety” enthused over the picture: Roger Corman), Cameron finished a draft script in “a blazing, cinematic comic book, full of virtuoso May 1982. After some trouble finding industry back- moviemaking, terrific momentum, solid performances ers, Orion agreed to distribute the picture with and a compelling story.” Janet Maslin for the “New Hemdale Pictures financing it. -

Movie Store Collections- Includes Factory Download Service

Kaleidescape Movie Store Collections- Includes Factory Download Service. *Content Availability Subject to Change. Collection of 4K Ultra HD & 4K HDR Films Academy Award Winners- Best Picture Collection of Family Films Collection of Concerts Collection of Best Content from BBC Our Price $1,250* Our Price $1,450* Our Price $2,450* Our Price $625* Our Price $650* MSCOLL-UHD MSCOLL-BPW MSCOLL-FAM MSCOLL-CON MSCOLL-BBC 2001: A Space Odyssey 12 Years a Slave Abominable Adele: Live at the Royal Albert Hall Blue Planet II A Star Is Born A Beautiful Mind Aladdin Alicia Keys: VH1 Storytellers Doctor Who (Season 8) Alien A Man for All Seasons Alice in Wonderland Billy Joel: Live at Shea Stadium Doctor Who (Season 9) Apocalypse Now: Final Cut All About Eve April and the Extraordinary World Celine Dion: Taking Chances World Tour - The Concert Doctor Who (Season 10) Avengers: Endgame All Quiet on the Western Front Babe Eagles: Farewell 1 Tour — Live from Melbourne Doctor Who (Season 11) Avengers: Infinity War All the King's Men Back to the Future Elton John: The Million Dollar Piano Doctor Who Special 2012: The Snowmen Baby Driver Amadeus Back to the Future Part II Eric Clapton: Slowhand at 70 - Live at the Royal Albert Hall Doctor Who Special 2013: The Day of the Doctor Blade Runner 2049 American Beauty Back to the Future Part III Genesis: Three Sides Live Doctor Who Special 2013: The Time of the Doctor Blade Runner: The Final Cut An American in Paris Beauty and the Beast Hans Zimmer: Live in Prague Doctor Who Special 2014: Last Christmas Blue Planet II Annie Hall Cars INXS: Live Baby Live Doctor Who Special 2015: The Husbands of River Song Bohemian Rhapsody Argo Cars 2 Jackie Evancho: Dream with Me in Concert Doctor Who Special 2016: The Return of Doctor Mysterio Chinatown Around the World in 80 Days Cars 3 Jeff Beck: Performing This Week.. -

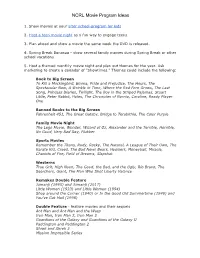

NCRL Movie Program Ideas

NCRL Movie Program Ideas 1. Show movies at your after school-program for kids 2. Host a teen movie night as a fun way to engage teens 3. Plan ahead and show a movie the same week the DVD is released. 4. Spring Break Bonanza - show several family movies during Spring Break or other school vacations 5. Host a themed monthly movie night and plan out themes for the year. Ask marketing to create a calendar of "Showtimes." Themes could include the following: Book to Big Screen To Kill a Mockingbird, Emma, Pride and Prejudice, The Hours, The Spectacular Now, A Wrinkle in Time, Where the Red Fern Grows, The Last Song, Princess Diaries, Twilight, The Boy in the Striped Pajamas, Stuart Little, Peter Rabbit, Holes, The Chronicles of Narnia, Coraline, Ready Player One Banned Books to the Big Screen Fahrenheit 451, The Great Gatsby, Bridge to Terabithia, The Color Purple Family Movie Night The Lego Movie, Wonder, Wizard of Oz, Alexander and the Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day, Flubber Sports Movies Remember the Titans, Rudy, Rocky, The Natural, A League of Their Own, The Karate Kid, Creed, The Bad News Bears, Hoosiers, Moneyball, Miracle, Chariots of Fire, Field of Dreams, Slapshot Westerns True Grit, High Noon, The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly, Rio Bravo, The Searchers, Giant, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance Remakes Double Feature Jumanji (1995) and Jumanji (2017) Little Women (1933) and Little Women (1994) Shop around the Corner (1940) or In the Good Old Summertime (1949) and You’ve Got Mail (1998) Double Feature - feature movies