Experiential Learning

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Old Woman and the Eagle

The Old Woman and the Eagle Text copyright © 2002 by The Estate of Idries Shah by Illustrations copyright © 2002 by Natasha Delmar Idries Shah ALL RIGHTS RESERVED No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, except as may be expressly permitted by the 1976 Copyright Act or in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed in writing to Hoopoe Books, PO Box 381069, Cambridge MA 02238-1069 First Edition 2003 Second Impression 2005 Published by Hoopoe Books, a division of The Institute for the Study of Human Knowledge ISBN 1-883536-27-8 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Shah, Idries, 1924- The old woman and the eagle / by Idries Shah ; illustrated by Natasha Delmar. p. cm. Summary: A Sufi teaching tale from Afghanistan about an old woman who insists that an eagle must really be a pigeon. ISBN 1-883536-27-8 -- ISBN 1-883536-28-6 (alk. paper) [1. Folklore--Afghanistan.] I. Delmar, Natasha, ill. II. Title. PZ8.1.S47 O1 2002 398.2’09581’02--dc21 [E] 2002068666 Visit www.hoopoekids.com for a complete list of Hoopoe titles, CDs, HOOPOE BOOKS DVDs and parent/teacher guides. BOSTON nce upon a time, when cups were plates and when knives and forks grew in the ground, there was an old woman who had never seen an eagle. One day, an eagle was flying high in the sky and decided to stop for a rest. -

Transcendent Philosophy an International Journal for Comparative Philosophy and Mysticism

Volume 11. December 2010 Transcendent Philosophy An International Journal for Comparative Philosophy and Mysticism Editor Transcendent Philosophy Journal is an academic Seyed G. Safavi peer-reviewed journal published by the London SOAS, University of London, UK Academy of Iranian Studies (LAIS) and aims to create a dialogue between Eastern, Western and Book Review Editor Islamic Philosophy and Mysticism is published in Sajjad H. Rizvi December. Contributions to Transcendent Philosophy Exeter University, UK do not necessarily reflect the views of the editorial board or the London Academy of Iranian Editorial Board Studies. G. A’awani, Iranian Institue of Philosophy, Iran Contributors are invited to submit papers on the A. Acikgenc, Fatih University, Turkey following topics: Comparative studies on Islamic, M. Araki, Islamic Centre England, UK Eastern and Western schools of Philosophy, Philosophical issues in history of Philosophy, Issues S. Chan, SOAS University of London, UK in contemporary Philosophy, Epistemology, W. Chittick, State University of New York, USA Philosophy of mind and cognitive science, R. Davari, Tehran University, Iran Philosophy of science (physics, mathematics, biology, psychology, etc), Logic and philosophical G. Dinani, Tehran University, Iran logic, Philosophy of language, Ethics and moral P.S. Fosl, Transylvania University, USA philosophy, Theology and philosophy of religion, M. Khamenei, SIPRIn, Iran Sufism and mysticism, Eschatology, Political Philosophy, Philosophy of Art and Metaphysics. B. Kuspinar, McGill University, Canada H. Landolt, McGill University, Canada The mailing address of the Transcendent Philosophy O. Leaman, University of Kentucky, USA is: Y. Michot, Hartford Seminary, Macdonald Dr S.G. Safavi Center, USA Journal of Transcendent Philosophy M. Mohaghegh-Damad, Beheshti University, Iran 121 Royal Langford 2 Greville Road J. -

The World of the Sufi

Books by Idries Shah Sufi Studies and Middle Eastern Literature The Sufis Caravan of Dreams The Way of the Sufi Tales of the Dervishes: Teaching-stories Over a Thousand Years Sufi Thought and Action Traditional Psychology, Teaching Encounters and Narratives Thinkers of the East: Studies in Experientialism Wisdom of the Idiots The Dermis Probe Learning How to Learn: Psychology and Spirituality in the Sufi Way Knowing How to Know The Magic Monastery: Analogical and Action Philosophy Seeker After Truth Observations Evenings with Idries Shah The Commanding Self University Lectures A Perfumed Scorpion (Institute for the Study of Human Knowledge and California University) Special Problems in the Study of Sufi Ideas (Sussex University) The Elephant in the Dark: Christianity, Islam and the Sufis (Geneva University) Neglected Aspects of Sufi Study: Beginning to Begin (The New School for Social Research) Letters and Lectures of Idries Shah Current and Traditional Ideas Reflections The Book of the Book A Veiled Gazelle: Seeing How to See Special Illumination: The Sufi Use of Humour The Mulla Nasrudin Corpus The Pleasantries of the Incredible Mulla Nasrudin The Subtleties of the Inimitable Mulla Nasrudin The Exploits of the Incomparable Mulla Nasrudin The World of Nasrudin Travel and Exploration Destination Mecca Studies in Minority Beliefs The Secret Lore of Magic Oriental Magic Selected Folktales and Their Background World Tales A Novel Kara Kush Sociological Works Darkest England The Natives are Restless The Englishman‟s Handbook Translated by Idries Shah The Hundred Tales of Wisdom (Aflaki‟s Munaqib) THE WORLD OF THE SUFI An anthology of writings about Sufis and their work Introduction by IDRIES SHAH ISF PUBLISHING Copyright © The Estate of Idries Shah The right of the Estate of Idries Shah to be identified as the owner of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 Nortfi Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Order Number 9218972 The path of love: Sufism in the novels of Doris Lessing Galin, Muge N., Ph.D. The Ohio State University, 1992 UMI 300 N. -

The Shah Movement Idries Shah and Omar Ali-Shah

The Shah Movement Idries Shah and Omar Ali-Shah PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Tue, 05 Jul 2011 04:52:24 UTC Contents Articles Idries Shah 1 Omar Ali-Shah 16 Institute for the Study of Human Knowledge 18 The Institute for Cultural Research 21 Saira Shah 24 References Article Sources and Contributors 26 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 27 Article Licenses License 28 Idries Shah 1 Idries Shah Idries Shah Born Simla, India Died 23 November 1996London, UK Occupation Writer, publisher Ethnicity Afghan, Indian, Scottish Subjects Sufism, psychology Notable work(s) The Sufis The Subtleties of the Inimitable Mulla Nasrudin The Exploits of the Incomparable Mulla Nasrudin Thinkers of the East Learning How to Learn The Way of the Sufi Reflections Kara Kush Notable award(s) Outstanding Book of the Year (BBC "The Critics"), twice; six first prizes at the UNESCO World Book Year in 1973 Children Saira Shah, Tahir Shah, Safia Shah Signature [1] also known as Idris Shah, né Sayed Idries ,(هاش سیردا :Idries Shah (16 June, 1924 – 23 November, 1996) (Persian was an author and teacher in the Sufi tradition who wrote over three dozen ,(يمشاه سيردإ ديس :el-Hashimi (Arabic Idries Shah 2 critically acclaimed books on topics ranging from psychology and spirituality to travelogues and culture studies. Born in India, the descendant of a family of Afghan nobles, Shah grew up mainly in England. His early writings centred on magic and witchcraft. In 1960 he established a publishing house, Octagon Press, producing translations of Sufi classics as well as titles of his own. -

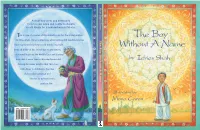

The Boy Without a Name

I d r i e s S h a h A small boy seeks and eventually / C finds his own name and is able to discard a r o an old dream for a new and wonderful one. n This is one of a series of illustrated books for the young written by Idries Shah, whose collections of narratives and teaching stories T h have captivated the hearts and minds of people e B from all walks of life. It belongs to a tradition o y of storytelling from the Middle East and Central W i t Asia that is more than a thousand years old. h o Among the many insights that this story u t introduces to children is the idea A that it takes patience and N a resolve to achieve one’s m e goals in life. Text copyright © 2000 by The Estate of Idries Shah Illustrations copyright © 2000 by Mona Caron ALL RIGHTS RESERVED The Boy Without A Name No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, except as may be expressly permitted by the 1976 Copyright Act or in writing from by the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed in writing to Hoopoe Books, PO Box 381069, Cambridge MA 02238-1069 Idries Shah First Edition 2000 Reprint Edition 2007 Paperback Edition 2007 Spanish English Hardcover Edition 2007 Spanish English Paperback Edition 2007 Published by Hoopoe Books, a division of The Institute for the Study of Human Knowledge Visit www.hoopoekids.com for a complete list of Hoopoe titles, CDs, DVDs, an introduction on the use of Teaching-Stories TM Learning that Lasts , and parent/teacher guides ISBN-10: 1-883536-20-0 ISBN-13: 978-1-883536-20-6 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Shah, Idries, 1924- The boy without a name / written by Idries Shah ; illustrated by Mona Caron.— 1st ed. -

The Way of the Sufi Books by Idries Shah

The Way of the Sufi Books by Idries Shah Sufi Studies and Middle Eastern Literature The Sufis Caravan of Dreams The Way of the Sufi Tales of the Dervishes: Teaching-stories Over a Thousand Years Sufi Thought and Action Traditional Psychology, Teaching Encounters and Narratives Thinkers of the East: Studies in Experientialism Wisdom of the Idiots The Dermis Probe Learning How to Learn: Psychology and Spirituality in the Sufi Way Knowing How to Know The Magic Monastery: Analogical and Action Philosophy Seeker After Truth Observations Evenings with Idries Shah The Commanding Self University Lectures A Perfumed Scorpion (Institute for the Study of Human Knowledge and California University) Special Problems in the Study of Sufi Ideas (Sussex University) The Elephant in the Dark: Christianity, Islam and the Sufis (Geneva University) Neglected Aspects of Sufi Study: Beginning to Begin (The New School for Social Research) Letters and Lectures of Idries Shah Current and Traditional Ideas Reflections The Book of the Book A Veiled Gazelle: Seeing How to See Special Illumination: The Sufi Use of Humour The Mulla Nasrudin Corpus The Pleasantries of the Incredible Mulla Nasrudin The Subtleties of the Inimitable Mulla Nasrudin The Exploits of the Incomparable Mulla Nasrudin The World of Nasrudin Travel and Exploration Destination Mecca Studies in Minority Beliefs The Secret Lore of Magic Oriental Magic Selected Folktales and Their Background World Tales A Novel Kara Kush Sociological Works Darkest England The Natives Are Restless The Englishman’s Handbook Translated by Idries Shah The Hundred Tales of Wisdom (Aflaki’s Munaqib) The Way of the Sufi Idries Shah ISF PUBLISHING Copyright © The Estate of Idries Shah The right of the Estate of Idries Shah to be identified as the owner of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. -

The Silly Chicken Stories by Idries Shah, Learns to Speak As We Do

Idries Shah • Jef f Jackson Written by Idries Shah The sixth title in this award-winning series of children’s stories by Idries Shah, The Silly Chicken is the delightful tale of a chicken who learns to speak as we do. What follows will intrigue young children and, at the same time, alert them in a very amusing way to the dangers of being too gullible. This tale is one of the many hundreds of Sufi develop- mental stories collected by Idries Shah from oral and written sources in Central Asia and the Middle East. For more than a thousand years this story has entertained young people and helped to foster in them the ability to examine their assumptions and to think for themselves. This is illustrator/animator Jeff Jackson’s first children's book. It expresses his unique ability to create a lively and amusing world, rich in color, and one in which anything can happen. His illustrations are full of visual delights and details faithful to the part of the world from which this story comes. Illustrated by Jeff Jackson Text copyright 2000 by The Estate of Idries Shah Illustrations copyright 2000 by Jeff Jackson ALL RIGHTS RESERVED No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, except as may be expressly permitted by the 1976 Copyright Act or in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed in writing to Written by Hoopoe Books, PO Box 381069, Cambridge MA 02238-1069 Idries Shah First Edition 2000 Second Impression 2005 Illustrated by Jeff Jackson Published by Hoopoe Books, a division of The Institute for the Study of Human Knowledge Visit www.hoopoekids.com for a complete list of Hoopoe titles, CDs, DVDs and parent/teacher guides. -

Neem, the Half-Boy

I D R I E S S NEEM THE HALF- BOY Because she fails to follow the precise instructions given to her by H Arif the Wise Man, the Queen of Hich-Hich gives birth to a half-boy. A How this happens and how Neem, the half-boy, becomes whole is a H BY / story that has been told and retold, by campfire and candlelight, to M children all over the Middle East for more than a thousand years. O IDRIES SHAH R For over 30 years, Idries Shah’s collections of narratives and teaching I stories from the Sufi tradition have captivated the hearts and minds of & R people from all walks of life. This is the first in a series of books for E the young. V E L Midori Mori and Robert Revels both live and work in San Francisco. S They are graduates of the Academy of Art College in San Francisco. N E E M T H E H A L F - B O Y ILLUSTRATED BY MIDORI MORI & ROBERT REVELS Text copyright 1998 by The Estate of Idries Shah Illustrations copyright 1998 by Midori Mori & Robert Revels NEEM THE HALF-BOY ALL RIGHTS RESERVED No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, except as may be expressly permitted by the BY IDRIES SHAH 1976 Copyright Act or in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed in writing to Hoopoe Books, PO Box 381069, Cambridge MA 02238-1069. -

Sufi Masters

Sufi Masters Enter the living world of the Sufi mystics and experience the extraordinary ... the teachers and teachings of the ancient and contemporary mystical traditions of Sufism, the masters of wisdom, esoteric knowledge and self-realization. Explore millennia-old traditions of spiritual practices, Sufi teachings of inner knowledge, self-realization, and spiritual enlightenment through the finest collection of books on Sufi teachings and practices by Sufi masters, teachers, scholars and authors. These are the teachings, experiences and traditions of the extraordinary sheikhs of the world-wide mystical tradition of Sufism: the exploration of the meaning of human life and activity, the nature of human consciousness, the descriptions of subtle states of being and the manifestation of spiritual dimensions within the universal mind. SUFI MASTERS http://www.sufibooks.com/sufimasters.html (1 of 29) [6/18/2001 8:19:24 AM] Sufi Masters THE KEY TO SALVATION: WELLSPRINGS OF WISDOM A SUFI MANUAL OF INVOCATION A translation (with commentary) of "Kitab In its first English translation, this important work al-Yanabi" by Abu Ya'qub al-Sijistani, this is an by Ibn 'Ata' Allah Al-Iskandari, the third great investigation of al-Sijistani's highly original master of the Shadhili Sufi Order, contains the combination of scientific Neoplatonism and an principles of actual Sufi mystical practices. It sheds Ismaili interpretation of Islam. Explored are a rich a new light on sacred invocation and assorted range of topics including the intellect and the soul, practices such as the spiritual retreat. Lucid in creation and prophecy in Islam, the Christian cross, style, it also offers a glimpse into the 7th Islamic the Word of God, the nature of evil, and the century Sufi world. -

A Living Organic Spiritual Teaching

A LIVING ORGANIC SPIRITUAL TEACHING ‘We work in all places and at all times .’ Saying Flexibility and Adaptability The ‘Great Teaching’ is universal and timeless in its essential nature, although its forms may alter as it adapts to changing circumstances. Such a developmental teaching is a living entity, essentially applicable at all times and in all circumstances, and is able to operate within any culture and in any language: ‘The clothes may vary, but the person is the same .’ The actual position and intention of the Tradition does not change, but it must have some flexibility because of changing social, geographical, political and other considerations. In former times we used verbal and other communications which were correct for the time. In primitive times we used primitive techniques, even though we had more sophisticated techniques which we could have used. The reason primitive techniques were used was because there was nothing strange or hostile about them. (1) The Teaching is conveyed in response to the needs of the community to which it is directed. It presents itself in a form which is perceptible and comprehensible to each person in direct accordance with their individual needs and capacities. “People differ at different times – what is appropriate for one person in one civilization may not be useful for another. Conditions of life change, understandings progress and regress, and the ‘ground’ on which the Teaching is based changes. Since it is a ‘growing, organic process,’ it becomes different in different eras.” The principle of ‘time, place and people’ refers to projecting a teaching afresh in each time and culture, in accordance with the real characteristics of a situation. -

MODELS of INNER DEVELOPMENT the Four Elements

MODELS OF INNER DEVELOPMENT The Four Elements The stages of spiritual development have been allegorized, as a teaching framework, in the form of the four elements: Earth, Water, Air and Fire. The order of the elements represents increasing degrees of refinement and decreasing levels of density and materiality. The lowest stage ‘Earth’ is the coarsest degree of matter and denotes passivity and fixation. At this point individuals are still conditioned by the grosser levels of manifestation, whether sensation, emotion, thought or action, in a manner which precludes any real understanding: The stage of ‘Humanity’ is that of the ordinary man or woman, lacking flexibility, given to ‘earthly’ behaviour and also fixed by habit and training into certain beliefs. Hence its symbol, EARTH: a static condition. It is also known as the ‘Condition of Law,’ in which people act according to almost inescapable rules. These rules may be seen as the interplay of everyone’s inherited susceptibility to training and the training itself. This is the stage of most people, characterized by its relative immo- bility as ‘Mineral.’ It includes many, if not most, of the people who imagine them- selves to be spiritually-minded: the heavily conditioned ones. (1) ‘Water’ symbolizes the stage of potentiality when an individual enters the spiritual path and is able to exercise some capacities towards self-realization. Since a certain amount of growth and movement takes place at this stage, it is sometimes called the ‘Vegetable’ stage: The stage of water, as distinct from earth, marks a very significant period in the development of consciousness: because whereas earth cannot be combined with earth except as a coarse physical mixture, water (the subtler and purer part of the human being) can be mixed with water (the subtler and purer element of a higher consciousness).