Chapter 1: Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Retail of Food Products in the Baltic States

RETAIL OF FOOD PRODUCTS IN THE BALTIC STATES FLANDERS INVESTMENT & TRADE MARKET SURVEY Retail of food products in the Baltic States December 2019 Flanders Investment & Trade Vilnius Retail of Food Products in the Baltic States| December 2019 1 Content Executive summary ................................................................................................................................. 3 Overview of the consumption market Baltic States ................................................................................ 4 Economic forecasts for the Baltic States ............................................................................................. 4 Lithuania .......................................................................................................................................... 4 Latvia ............................................................................................................................................... 5 Estonia ............................................................................................................................................. 6 Structure of distribution and market entry in the Baltic States ............................................................ 13 Structure ............................................................................................................................................ 13 Market entry ..................................................................................................................................... 14 Key -

I CENTRI COMMERCIALI AL DETTAGLIO in ITALIA: Aprile 2013 Fonte: Infocommercio

I CENTRI COMMERCIALI AL DETTAGLIO IN ITALIA: aprile 2013 Fonte: Infocommercio DENOMINAZIONE E LOCALITÀ SUPERFICIE GLA (mq) LOCOMOTIVA (mq) DENOMINAZIONE E LOCALITÀ SUPERFICIE GLA (mq) LOCOMOTIVA (mq) ABRUZZO (totale n 36) Il Borgo - Viale Della Repubblica 8/A - 67039 Sulmona - Aq 7000 Coop (1.800 mq) Amiternum - Via E. Fermi Loc. Pettino - 67100 L’Aquila - AQ 6500 No Alimen tare Gran Sasso Shopping - Via Nazionale Loc. Piano D’Accio - 64100 Teramo - Te 29700 E.Leclerc - Conad (7.200 mq) Il Parco - Via Tiburtina Km. 110.400 Loc. Capp. dei Marsi : Il Molino - Via Giuseppe Misticoni - 65127 Pescara - Pe 7250 Carrefour Market (1.450 mq) a I Marsi - ssTiburtina Valeria Km. 112,215 - 67051 Avezzano - Aq 18000 Ipercoop (5.000 mq) 67068 Scurcola Marsicana - Aq 7e 375 Pam (3.685 mq) r Marsica Città Shopping - Via Tiburtina Valeria Km 111,500 e Ortona Center - Contr. Santa Liberata 1 - 66026 Ortona - Ch 18000 Iper La Grande I (6.000 mq) v i 67068 Scurcola Marsicana - Aq 4r 530 Maxisidis (1.195 mq) Insieme - Contr. Piano Sant’angelo 190 - 66050 San Salvo - Ch 6000 Conad Superstore (1.520 mq) c Ovidio - S.S.. 17 Appenninica Km.96 Loc. Zona Ind. - 67039 Sulmona - Aq 6s 000 Ipersidis (2.500 mq) Galleria Commerciale Meridiana - Via Rocco Carabba 1 ang. e l Colonnetta - Via Colonnetta 343 - 66100 Chieti - Ch 5i 900 Conad Superstore (1.400 mq) Viale della Stazione - 67100 L’Aquila - Aq 5900 Lidl (850 mq) b o i f g Theate Center - Via Brigata Maiella 56 ang. Via Spezioli 1 - 66100 Chieti - Ch 12000 n Conad Superstore (1.230 mq) Delfino - Via Nazionale Adriatica Nord 211 - 65125 Pescara - Pe 12700 Maxi Tigre (1.450 mq) i g . -

Cushman & Wakefield Global Cities Retail Guide

Cushman & Wakefield Global Cities Retail Guide Italy is a modern and cosmopolitan country, a land of creativity, centrally located in the heart of the Mediterranean. It is at the crossroads linking the North and South of Europe. Italian style, innovation, creativity and love for tradition are all key success factors of the “Made-in-Italy” brand in the competitive world market. Shopping in Italy is also a serious business. Italians take price, style and quality into careful consideration before buying. More recently shopping habits have become more polarised as Italian shoppers are increasingly looking for value through discount and private label goods, though luxury and premium brand retailers’ sales have proved resilient. The shopping streets in all towns and cities are also places to be seen on the early evening “passeggiata.” Compared to many Western European markets the Italian retail sector remains highly fragmented and is dominated by small independent businesses, the majority of which operate as single outlets. ITALY OVERVIEW Cushman & Wakefield | Italy | 2019 1 ITALY ECONOMIC OVERVIEW ECONOMIC SUMMARY ECONOMIC INDICATORS* 2018 2019F 2020F 2021F 2022F GDP growth 0.8 -0.1 0.4 0.5 0.7 Consumer spending 0.6 0.3 0.4 0.6 0.6 Industrial production 0.7 -0.6 0.6 0.7 0.6 Investment 3.2 -0.3 0.4 0.7 0.8 Unemployment rate (%) 10.6 10.8 10.5 10.4 10.2 Inflation 1.1 0.9 0.9 1.1 1.7 US$/€ (average) 1.2 1.1 1.2 1.2 1.3 Interest rates Short Term (%) 0.0 0.0 0.2 0.5 0.7 Interest rates 10-year (%) 2.6 2.9 3.4 3.7 4.1 ECONOMIC BREAKDOWN RETAIL SALES GROWTH: % CHANGE ON PREVIOUS YEAR Population 60.5 Million (2018) GDP (nominal) US$2.07 Trillion (2018) ITALY 2018 2019F 2020F 2021F 2022F Retail Volume* Public Sector Balance -2.1% of GDP (2018) -0.2 0.9 0.7 0.9 0.8 Public Sector Debt 154% of GDP (2018) Current Account Balance 2.5% of GDP (2018) The election in March 2018 resulted in a hung parliament with a majority for the populist parties (Five Star Movement and Lega) and formal Parliament consultations have now started. -

Centrali D'acquisto E Gruppi Distributivi Alimentari in Italia

LE GUIDE DI CENTRALI D’ACQUISTO E GRUPPI DISTRIBUTIVI ALIMENTARI IN ITALIA 2018 1 PREFAZIONE Eccoci giunti alla terza edizione della Guida alle Centrali d’acquisto e ai Gruppi distributivi alimentari in Italia, quella del 2018. In realtà, per come è stata concepita, il concetto di guida annuale sta davvero stretto alla nostra pubblicazione. Indubbiamente non è la prima iniziativa editoriale del genere. A differenza di analoghe guide di tipo cartaceo, destinate a invecchiare precocemente nella rappresentazione di un mondo distributivo in rapida e continua evoluzione, la nostra è stata immaginata come un database informa- tico in grado di sfruttare la velocità del web e la flessibilità del digitale, prestandosi a essere costantemente aggiornato e a recepire facilmente correzioni e integrazioni delle informazioni riportate. Ecco perché nel corso dell’anno sono previste pubblicazioni che riprendono le variazioni intervenute man mano nell’assetto dei centri decisionali e di acquisto nel settore alimentare della distribu- zione moderna. La Guida alle Centrali d’acquisto e ai Gruppi distributivi alimentari in Italia si configura pertanto come un appunta- mento annuale continuativo, un evento atteso da molti nostri lettori che ricercano uno strumento agile e di facile consultazione per essere sempre aggiornati sulle novità del settore. Anche l’edizione 2018 conferma la stessa impostazione delle precedenti. A un quadro prospettico introduttivo delle relazioni di tipo orizzontale e delle integrazioni di tipo verticale che caratterizzano la Grande Distribuzione Organizzata (con una panoramica delle Supercentrali europee, di quelle nazionali e delle Centrali d’acquisto che a queste ultime fanno capo) segue la rassegna dettagliata delle caratteristiche strutturali dei vari gruppi distributivi italiani. -

2016 Italian Food Retail and Distribution Sector Report Retail Foods Italy

THIS REPORT CONTAINS ASSESSMENTS OF COMMODITY AND TRADE ISSUES MADE BY USDA STAFF AND NOT NECESSARILY STATEMENTS OF OFFICIAL U.S. GOVERNMENT POLICY Required Report - public distribution Date: 12/13/2016 GAIN Report Number: IT1655 Italy Retail Foods 2016 Italian Food Retail and Distribution Sector Report Approved By: Fred Giles Prepared By: Dana Biasetti Report Highlights: In 2015, after years of deep recession, Italy showed signs of a long-awaited economic recovery. Affected by diminished disposable incomes and high unemployment, Italian consumers remain very price conscious and tend to seek discounts. With tighter wallets, their changing shopping strategies indicate that now more than ever, they are avidly pursuing true bargains. Major retail brands have embraced the “everyday low price” strategies, increasing their private label ranges. This report provides an overview of the grocery retail sector and how best to place U.S. products in the Italian market. 1 Post: Rome Executive Summary: Section I. Market Summary Italy has a diversified industrial economy, divided into a developed industrial north and a less- developed agricultural south, with high unemployment. The Italian economy is driven in large part by the manufacture of high-quality consumer goods produced by small and medium-sized enterprises, many of them family owned. Italy is the third-largest economy in the euro-zone, but exceptionally high public debt burdens and structural impediments to growth have rendered it vulnerable to scrutiny by financial markets. Italy’s GDP is estimated at $2.175 trillion, and it has a per capita GDP of $35,800. Italy has few natural resources, with much land unsuited for farming. -

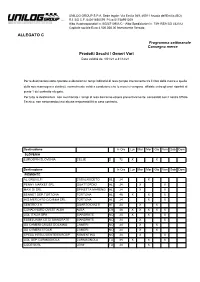

ALLEGATO C Prodotti Secchi / Generi Vari

UNILOG GROUP S.P.A. Sede legale: Via Emilia 369, 40011 Anzola dell'Emilia (BO) R.I. BO C.F. 04011850379 P.Iva 01738951209 Albo Autotrasportatori n. BO/3710901/C - Albo Spedizionieri n. 749 -REA BO 332312 Capitale sociale Euro 3.500.000,00 Interamente Versato ALLEGATO C Programma settimanale Consegna merce Prodotti Secchi / Generi Vari Data validità da 1/01/21 a 31/12/21 Per le destinazioni sotto riportate evidenziamo i tempi indicativi di resa (tempo intercorrente tra il ritiro della merce e quello della sua riconsegna a destino), normalmente validi a condizione che le merci ci vengano affidate entro gli orari riportati al punto 1 del contratto allegato. Per tutte le destinazioni non menzionate i tempi di resa dovranno essere preventivamente concordati con il nostro Ufficio Tecnico, non assumendoci noi alcuna responsabilità in caso contrario. Destinazione In Ore Lun Mar Mer Gio Ven Sab Dom SLOVENIA EUROSPIN SLOVENIA CELJE S 72 X X Destinazione In Ore Lun Mar Mer Gio Ven Sab Dom PIEMONTE AL.GRO/ALFI CASALNOCETO AL 24 X PENNY MARKET SRL QUATTORDIO AL 24 X X MAXI DI SRL SPINETTA MARENG AL 24 X X BENNET DEP.TORTONA TORTONA AL 48 X X X IN'S MERCATO C/O B&M SRL TORTONA AL 24 X X CENTRO 3 A QUARTO D'ASTI AT 24 X X CONAD NORD OVEST ALBA ALBA CN 48 X X X X X LIDL ITALIA SPA BIANDRATE NO 24 X X X ESSELUNGA CE.DI BIANDRATE BIANDRATE NO 24 X X GS CAMERI CROSS DOCKING CAMERI NO 24 X X GS CAMERI STOCK CAMERI NO 24 X X SPESA INTELLIGENTE/EUROSP ROMENTINO NO 24 X X LIDL DEP.CARMAGNOLA CARMAGNOLA TO 48 X X X CODE'SCRL LEINI' TO 24 X Destinazione In Ore -

Elenco Dei Punti Vendita Della Grande Distribuzione Organizzata Aderenti

Data ultimo aggiornamento: Settembre 2021 ELENCO DEI PUNTI VENDITA DELLA GRANDE DISTRIBUZIONE ORGANIZZATA ADERENTI ATS di Denominazi Indirizzo Comune Provincia Circuito Riferimento one Fornitore ATS DELLA BENNET - LENTATE SUL STRADA STATALE 35 LENTATE SUL MONZA E DELLA BENNET BRIANZA SEVESO DEI GIOVI 249 SEVESO BRIANZA ATS DELLA BENNET S.P.A VIA LARIO 17 MONZA MONZA E DELLA BENNET BRIANZA BRIANZA ATS DELLA BENNET SPA - VIA FRANCESCO CASATENOVO LECCO BENNET BRIANZA CASATENOVO CASATI 28 ATS DELLA BENNET SPA - LECCO CORSO CARLO LECCO LECCO BENNET BRIANZA CORSO CARLO ALBERTO 120 ALBERTO ATS DELLA BENNET SPA - LECCO VIA GIOVANNI LECCO LECCO BENNET BRIANZA VIA AMENDOLA AMENDOLA ATS DELLA BENNET SPA - PESCATE VIA STATALE 7 PESCATE LECCO BENNET BRIANZA ATS DELLA BENNET- MONZA E VIALE LOMBARDIA BRUGHERIO MONZA E DELLA BENNET BRIANZA BRIANZA 264 BRIANZA ATS DELLA CARREFOUR EXPRESS VICOLO SAN LECCO LECCO CARREFOUR BRIANZA GIACOMO ATS DELLA CARREFOUR EXPRESS VIA PRETORIO 4 MONZA MONZA E DELLA CARREFOUR BRIANZA MONZA - VIA BRIANZA PRETORIO ATS DELLA CARREFOUR EXPRESS VIA FELICE MONZA MONZA E DELLA CARREFOUR BRIANZA MONZA CAVALLOTTI CAVALLOTTI 131 BRIANZA ATS DELLA CARREFOUR EXPRESS VIA BERGAMO 2 MONZA MONZA E DELLA CARREFOUR BRIANZA MONZA-VIA BERGAMO BRIANZA ATS DELLA CARREFOUR EXPRESS VIA GIOVANNI MONZA MONZA E DELLA CARREFOUR BRIANZA VIA PERGOLESI BATTISTA BRIANZA PERGOLESI 33 ATS DELLA CARREFOUR EXPRESS VIALE IGINIO ROTA VIMERCATE MONZA E DELLA CARREFOUR BRIANZA VIMERCATE (MI) VIA BRIANZA ROTA ATS DELLA CARREFOUR IPER VIA PREALPI 41 GIUSSANO MONZA E DELLA CARREFOUR BRIANZA GIUSSANO BRIANZA ATS DELLA CARREFOUR IPER VIA ISONZO 5 LIMBIATE MONZA E DELLA CARREFOUR BRIANZA LIMBIATE BRIANZA Elenco dei punti vendita della Grande Distribuzione Organizzata aderenti Pag. -

The Supply Chain Initia- Tive, Together for Good Trading Practices”, Aj

Today 16 September marks the official launch of "The Supply Chain Initia- tive, together for good trading practices”, a joint initiative by seven EU- level associations with the aim of ensuring fairness in commercial rela- tions along the food supply chain. The associations involved in spear- heading this Initiative represent the food and drink industry (FoodDrinkEurope), the branded goods manufacturers (AIM), the retail sector (the European Retail Round Table (ERRT), EuroCommerce, Euro- Coop and UGAL), and agricultural traders (CELCAA). On this special occasion, the names of the companies having expressed their intent to sign up to the Supply Chain Initiative are official- ly announced. 82 companies from across the entire EU have expressed their inten- tion to register. Half of these are local companies. Taking into ac- count the subsidiaries of international groups, 454 operating com- panies are signed up. Manufacturing companies that have expressed their intent to register Amanda Seafoods Arla Foods Amba Beauvais Foods Bongrain SA Braüner A/S Carletti A/S Cloetta AB Coca Cola Enterprises Coca Cola Erfrischungsgetränke AG Coca-Cola HBC AG Coca-Cola Iberian Partners S.A. Coca-Cola Europe Group Daloon A/S DanCake Danaeg Manufacturing companies that have expressed their intent to register Danish Crown Danone DLG Food Easy Food Ferrero International SA Felix Abba Oy Fromageries Bel SA Fritz Schur Consumer Products Halloren Shokoladenfabrik AG Haugen-Gruppen AS GlaxoSmithKline Consumer Healthcare Europe Il Fornaio O. Kavli A/S Kellogg Company Kims A/S KOFF A/S Manufacturing companies that have expressed their intent to Kohberg Bakery Group A/S Mondelēz Europe Munakunta Mars Incorporated Müllers Hausmacher Wurst GmbH & Co KG Nestlé SA Nupo A/S Paulig Ltd PepsiCo Royal Unibrew Saarioninen Oy Schwartauer Werke GmbH & Co KGaA Stryhns Unilever Voldsted S/A The Whole Company S/A Wrigley Retail companies that have expressed their intent to Company Country Group Albert Heijn B.V. -

Ipermercati in Italia E Quote Di Mercato (Iper+Super+Lis+Disc) Per Provincia 2017 MAP Fonte: Nielsen - Dati Al 1 Gennaio 2017

Ipermercati in Italia e quote di mercato (iper+super+lis+disc) per provincia 2017 MAP fonte: Nielsen - dati al 1 gennaio 2017 www.markup.it Interspar 3 Iper Poli 1 Bennet 1 82,1 % Conad Superstore 1 Aspiag Coop Superstore 2 Cadoro 1 Bennet 1 Bennet 1 Emisfero 1 Bennet 1 Bennet 7 Iperal 5 Carrefour Market 1 Iper Orvea 1 Auchan 1 Cadoro 1 Carrefour 2 Carrefour 1 Interspar 1 Bennet 3 Esselunga Superstore 1 BZ Carrefour Market 2 Ipercoop 1 Carrefour 2 D’Ambros 1 Ipercoop 2 Esselunga Superstore 4 64,8 Coop 1 Coop 3 Esselunga Superstore 4 % Super Visotto 1 Iperal 1 VB Interspar 3 Esselunga Superstore 7 Il Gigante 1 Iper 1 Il Gigante 3 Iper 1 Aspiag Bennet 3 Iperspar 1 Iper 2 Ipercoop 1 Bennet 1 Carrefour Market 2 Carrefour 1 SO 77,1 Panorama 2 Tigros 1 VB % Iperal 1 Esselunga Superstore 3 Gros Cidac 1 53,8 Esselunga Superstore 2 BL % Ipercoop 1 Il Gigante 3 TN Auchan 3 Auchan 3 SO Ipercoop 3 LC UD Bennet 1 Bennet 2 70,7 PN 47,3 Bennet 10 % Emisfero 1 % VA Aspiag Auchan 1 79,5 Esselunga Superstore 4 Carrefour 11 Ipercoop 1 % AO CO GO Bennet 2 Esselunga 1 Carrefour Market 3 BG 68,7 59,2 54,7 VI Ipersimply 1 Il Gigante 1 % Carrefour 2 56,9 Esselunga Superstore 3 % % MB 58,1 BI BI TV % Coop 1 % Iper 3 Il Gigante 4 Bennet 1 BS Aspiag 62,1 NO TS Esselunga Superstore 10 Coop 1 Ipercoop 7 NO Carrefour 1 VE % VA 44,7 MI Famila Superstore 1 Ipercoop 2 Conad Ipermercato 2 Carrefour Market 1 Famila Superstore 1 % Il Gigante 4 Famila Superstore 1 Mercatò 4 Famila Superstore 1 VR PD Ipercoop 2 51,1 52,9 VC Iper 2 % Panorama 1 % Ipercoop 1 CO BG Coop 1 Iper -

The Competitive Conduct of Consumer Cooperatives∗

The Competitive Conduct of Consumer Cooperatives∗ Marco Duarte,†Lorenzo Magnolfi‡and Camilla Roncoroni§ First Draft: January, 2019; This Draft: January 2020 Abstract Although consumer cooperatives are nominally operated in the interest of their members, their governance structure may allow managers to pursue their own objectives. This article tests empirically whether consumer cooperatives act as profit-maximizing agents. Using data and a structural model, we investigate whether the hypothesis of profit maximization can be rejected for consumer cooperatives operating in the Italian supermarket industry. We do not find significant deviations of cooperatives’ conduct from profit maximization. Counterfactual simulations indicate that full internalization of consumer surplus by cooperatives would increase consumer surplus by about 6% in the market we study. Keywords: Consumer cooperative, estimation of conduct, supermarket industry JEL Codes: L21, L22, L33 ∗We thank Jean-Francois Houde, Gaston Illanes, Simon Martin, Chris Sullivan and audiences at IIOC 2018, Midwest Macro 2018, EARIE 2018, Midwest IO Fest, University of Rochester-Simon, NAMES 2019 and EEA-ESEM 2019 for useful comments. We also thank Renata Gaineddenova and Howard Hsu for excellent research assistance. Support for this research was provided by the University of Wisconsin-Madison, Office of the Vice Chancellor for Research and Graduate Education with funding from the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation. All estimates and analyses in this article based on IRI data are by the authors and not by IRI. All estimates and analyses in this article based on Bank of Italy data are by the authors and not by the Bank of Italy. †Department of Economics, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1180 Observatory Drive, Madison WI, USA. -

Country Retail Scene Report

ITALY COUNTRY RETAIL SCENE REPORT August 2012 KANTAR RETAIL 6 More London Place, Tooley Street, London, UK / Tel. +44 (0)207 031 0251 / www.KantarRetail.com INFORMATION / INSIGHT / STRATEGY / EXECUTION © Kantar Retail 2012 245 First Street 6 More London Place T +44 (0) 207 0310272 Suite 1000 London F +44 (0) 207 0310270 Cambridge, MA 02142 SE1 2QY [email protected] USA UK www.kantarretail.com Index I. Key Themes .......................................................................................................... 2 II. Socio – Economic Background .............................................................................. 3 III. Key Players in the Grocery Retail Sector ............................................................ 11 IV. Grocery Retail Channels ..................................................................................... 19 V. Conclusion ........................................................................................................... 25 © 2012 KANTAR RETAIL | 2012 Italy Retail Scene | www.kantarretail.com 1 245 First Street 6 More London Place T +44 (0) 207 0310272 Suite 1000 London F +44 (0) 207 0310270 Cambridge, MA 02142 SE1 2QY [email protected] USA UK www.kantarretail.com I. Key Themes Private Label Due to the country’s difficult economic situation, Italian household spending is under pressure and shoppers are looking to cut their expenses as much as possible. Private labels are thus seen as a key way for shoppers to cut their grocery expenditure. Private labels are underdeveloped in Italy compared to France, representing only around 25% of sales, whereas French retailers can generate around 40% of their sales through their own brands. Italian retailers are aggressively expanding their assortments of private labels, and heavily promoting their own brands. National Champions The Italian grocery market is dominated by national retailers, from multi-channel retailers to discounters. These national champions accounted for 45% of the Italian grocery retail market in 2011. -

1 CARREFOUR Viale Giulio Cesare Novara 2 CARREFOUR MARKET C.So Trieste, 85 Novara 3 CARREFOUR MARKET Via Gnifetti, 80 Novara

1 CARREFOUR Viale Gilio Ceae Noaa 2 CARREFOUR MARKET C.o Tiee, 85 Noaa 3 CARREFOUR MARKET Via Gnifei, 80 Noaa 4 CARREFOUR MARKET Via Peai 2 Noaa 5 COOP Via Faa, 43 Noaa 6 COOP Coo XXIII Mao 200 Noaa 7 IPERCOOP Via Ugo Poio Noaa 8 LDL Via G. Gibellini 33 Noaa 9 LDL Via Caoai Felice 10 Noaa 10 TIGROS Via Caoai Felice 10 Noaa 11 LD MARKET Via Ca Vioio Veneo 3 Noaa 12 PENNY MARKET C.o Vecelli 203 Noaa 13 PENNY MARKET C.o Riogimeno 17 ang. Via Eopa Noaa 14 PENNY MARKET C.o 23 Mao, 363 Noaa 15 PENNY MARKET C.o Tiee, 64 Noaa 16 PENNY MARKET C.o della Vioia Noaa 17 BILLA Via pe Biandae, 28 Noaa 18 BILLA C.o XXIII Mao 230 Noaa 19 BILLA C.o Toino 33 Noaa 20 BILLA Via Mone S. Gabiele 52 Noaa 21 BILLA Via Camolei 13 Noaa 22 BILLA V.le G. Ceae 96 Noaa 23 BILLA Lago Paoe Noaa 24 BILLA Via Belami Noaa 25 U2 Via Umbia, 20 Noaa 26 CARREFOUR ( VELA) C.o Riogimeno Noaa 27 CARREFOUR EXPRESS Via Gnifei 22 Noaa 28 CARREFOUR EXPRESS Balado Paigiani 1 G/H Noaa 29 DOCKS Coo Vecelli, 91 Noaa 30 LDL Via Libe 16 Bellinago 31 BENNET Via Libe Bellinago 32 CARREFOUR MARKET Via Roma, 63 Biandae 33 TIGROS Via Noaa 24 Calignaga 34 COOP Via Ugo Focolo 32 Camei 35 CRAI C.o Sempione Km 6 Camei 36 SUPERDI' C.o Sempione Camei 37 DIMEGLIO Piaale Ialia, 12 Capignano Seia 38 SIGMA FARA ia Ceae Baii Faa Noaee 39 BILLA Coo Tiee 85 Galliae 40 LD MARKET Lago Ticoloe 1 Galliae 41 LDL Via Peoni 17 Galliae 42 IPERCOOP Via Moneneo Galliae 43 CARREFOUR MARKET Via IV Noembe Gignaco 44 SUPER A&O Viale Saione 4 Gignaco 45 MARGHERITA CONAD Via Sqaini 20 Momo 46 COOP Via Noaa, 99 Oleggio 47 FAMILA Via Camine 24 Oleggio 48 PENNY MARKET Via Noaa 105/c Oleggio 49 CARREFOUR MARKET Via dei Negi 36 Oleggio 50 CONAD Via Noaa, 55 Penae 51 CARREFOUR MARKET Via Noaa, 380 Romagnano Seia 52 BENNET Via Noaa Romagnano Seia 53 PENNY MARKET Via Noaa, 315 Romagnano Seia 54 LDL Via Rggeone Tecae 55 COOP Via G.