Shinto and Buddhist Metaphors in Departures Yoshiko Okuyama University of Hawaii at Hilo, [email protected]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

English 12: Science Fiction & Fantasy

English 12: Science Fiction & Fantasy TIME CONTENT/THEME CORE GOALS/SKILLS ASSESSMENT LITERATURE Fantasy - Unit #1 Literary Genres: Fantasy o Writing Assignments 1 Marking Period Literary Elements: Elements of Fantasy, Open Ended Questions o The Hero and the Crown Characterization, Point of View, Tone, Discussion Boards Theme, Plot Short Answers Literary Devices: figurative language, Annotated Bibliographies plot structure o Tests / Quizzes Interpret, compare, describe, analyze and Chapter Reviews evaluate literary devices Summative Assessments o Identify and assess effectiveness o Research Assignments of point of view Literary Analysis Articles o Identify and assess the o Projects effectiveness of tone and mood Multimedia Group Project Recognize and analyze the elements of fantasy writing o Anansi Boys Literary Genres: Fantasy o Maskerade Literature Circles – Fantasy Literary Elements: Elements of Fantasy, o Writing Assignments o Sunshine Characterization, Point of View, Tone, Open Ended Questions o Fevre Dream Theme, Plot o The Alchemist Discussion Boards Literary Devices: figurative language, Short Answers plot structure Annotated Bibliographies Interpret, compare, describe, analyze and o Projects evaluate literary devices Group Report o Identify and assess effectiveness of point of view o Identify and assess the effectiveness of tone and mood Recognize and analyze the elements of fantasy writing Vocabulary Word Acquisition and Usage o Writing Assignments Sadlier‐Oxford Books G and H Multiple Meaning/Roots -

The Zen Koan; Its History and Use in Rinzai

NUNC COCNOSCO EX PARTE TRENT UNIVERSITY LIBRARY Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2019 with funding from Kahle/Austin Foundation https://archive.org/details/zenkoanitshistorOOOOmiur THE ZEN KOAN THE ZEN KOAN ITS HISTORY AND USE IN RINZAI ZEN ISSHU MIURA RUTH FULLER SASAKI With Reproductions of Ten Drawings by Hakuin Ekaku A HELEN AND KURT WOLFF BOOK HARCOURT, BRACE & WORLD, INC., NEW YORK V ArS) ' Copyright © 1965 by Ruth Fuller Sasaki All rights reserved First edition Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 65-19104 Printed in Japan CONTENTS f Foreword . PART ONE The History of the Koan in Rinzai (Un-chi) Zen by Ruth F. Sasaki I. The Koan in Chinese Zen. 3 II. The Koan in Japanese Zen. 17 PART TWO Koan Study in Rinzai Zen by Isshu Miura Roshi, translated from the Japanese by Ruth F. Sasaki I. The Four Vows. 35 II. Seeing into One’s Own Nature (i) . 37 vii 8S988 III. Seeing into One’s Own Nature (2) . 41 IV. The Hosshin and Kikan Koans. 46 V. The Gonsen Koans . 52 VI. The Nanto Koans. 57 VII. The Goi Koans. 62 VIII. The Commandments. 73 PART THREE Selections from A Zen Phrase Anthology translated by Ruth F. Sasaki. 79 Drawings by Hakuin Ekaku.123 Index.147 viii FOREWORD The First Zen Institute of America, founded in New York City in 1930 by the late Sasaki Sokei-an Roshi for the purpose of instructing American students of Zen in the traditional manner, celebrated its twenty-fifth anniversary on February 15, 1955. To commemorate that event it invited Miura Isshu Roshi of the Koon-ji, a monastery belonging to the Nanzen-ji branch of Rinzai Zen and situated not far from Tokyo, to come to New York and give a series of talks at the Institute on the subject of koan study, the study which is basic for monks and laymen in traditional, transmitted Rinzai Zen. -

Representations of Pleasure and Worship in Sankei Mandara Talia J

Mapping Sacred Spaces: Representations of Pleasure and Worship in Sankei mandara Talia J. Andrei Submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Columbia University 2016 © 2016 Talia J.Andrei All rights reserved Abstract Mapping Sacred Spaces: Representations of Pleasure and Worship in Sankei Mandara Talia J. Andrei This dissertation examines the historical and artistic circumstances behind the emergence in late medieval Japan of a short-lived genre of painting referred to as sankei mandara (pilgrimage mandalas). The paintings are large-scale topographical depictions of sacred sites and served as promotional material for temples and shrines in need of financial support to encourage pilgrimage, offering travelers worldly and spiritual benefits while inspiring them to donate liberally. Itinerant monks and nuns used the mandara in recitation performances (etoki) to lead audiences on virtual pilgrimages, decoding the pictorial clues and touting the benefits of the site shown. Addressing themselves to the newly risen commoner class following the collapse of the aristocratic order, sankei mandara depict commoners in the role of patron and pilgrim, the first instance of them being portrayed this way, alongside warriors and aristocrats as they make their way to the sites, enjoying the local delights, and worship on the sacred grounds. Together with the novel subject material, a new artistic language was created— schematic, colorful and bold. We begin by locating sankei mandara’s artistic roots and influences and then proceed to investigate the individual mandara devoted to three sacred sites: Mt. Fuji, Kiyomizudera and Ise Shrine (a sacred mountain, temple and shrine, respectively). -

Religion and Culture

Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 40/2: 355–375 © 2013 Nanzan Institute for Religion and Culture review article Constructing Histories, Thinking Ritual Gatherings, and Rereading “Native” Religion A Review of Recent Books Published in Japanese on Premodern Japanese Religion (Part Two) Brian O. Ruppert Histories of Premodern Japanese Religion We can start with Yoshida Kazuhiko’s 吉田一彦 Kodai Bukkyō o yominaosu 古代仏 教 をよみ なお す (Tokyo: Yoshikawa Kōbunkan, 2006), since it seems in many ways like a founder and precursor of the range of works written recently concerning early and, to some extent, medieval Japanese religion. Yoshida, who has long attempted to overcome common misconceptions concerning early Buddhism, succinctly tries to correct the public’s “common sense” (jōshiki 常識). Highlights include clarifications, including reference to primary and secondary sources that “Shōtoku Taishi” is a historical construction rather than a person, and even the story of the destruction of Buddhist images is based primarily on continental Buddhist sources; “popular Buddhism” does not begin in the Kamakura period, since even the new Kamakura Buddhisms as a group did not become promi- nent until the late fifteenth century; discourses on kami-Buddha relations in Japan were originally based on Chinese sources; for early Japanese Buddhists (including Saichō, Kūkai, and so on), Japan was a Buddhist country modeling Brian O. Ruppert is an associate professor in the Department of East Asian Languages and Cul- tures, University of Illinois. 355 356 | Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 40/2 (2013) its Buddhism on the continent; and the term for the sovereign tennō, written as “heavenly thearch” 天皇, was based on Chinese religious sources and only used from the late seventh century. -

Recent Japanese Publications on Buddhism Hubert Durt

Recent Japanese Publications on Buddhism Hubert Durt To cite this version: Hubert Durt. Recent Japanese Publications on Buddhism. Cahiers d’Extrême-Asie, Ecole française d’Extrême-Orient, 1988, no. 4, p. 205-216. halshs-03134192 HAL Id: halshs-03134192 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-03134192 Submitted on 8 Feb 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Cahiers d'Extrême-Asie Recent Japanese Publications on Buddhism Hubert Durt Citer ce document / Cite this document : Durt Hubert. Recent Japanese Publications on Buddhism. In: Cahiers d'Extrême-Asie, vol. 4, 1988. Numéro spécial Etudes taoïstes I / Special Issue on Taoist Studies I en l'honneur de Maxime Kaltenmark. pp. 205-216; https://www.persee.fr/doc/asie_0766-1177_1988_num_4_1_927 Fichier pdf généré le 06/02/2019 REGENT JAPANESE PUBLICATIONS ON BUDDHISM Hubert Durt i. general reference works and works on indian and tibetan buddhism A. Dictionaries 1° Hayashima Kyôshô -^-l^tiïE (iêl^), Takasaki Jikidô jftl^ïËji; ($S) Bukkyô, Indo shisôjiten {AWc ' 4 V KSîli#^r (562 pp.) Tokyo, Shunjusha #ffcÉfc, 1987 9,300 Yen This "Dictionary of Indian and Buddhist Thought" is compiled by a large number of scholars, all signing their own articles and almost all of them connected with Tokyo University. -

Complete Poison Blossoms from a Thicket of Thorn : the Zen Records of Hakuin Ekaku / Hakuin Zenji ; Translated by Norman Waddell

The Publisher is grateful for the support provided by Rolex Japan Ltd to underwrite this edition. And our thanks to Bruce R. Bailey, a great friend to this project. Copyright © 2017 by Norman Waddell All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. ISBN: 978-1-61902-931-6 THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA Names: Hakuin, 1686–1769, author. Title: Complete poison blossoms from a thicket of thorn : the zen records of Hakuin Ekaku / Hakuin Zenji ; translated by Norman Waddell. Other titles: Keisåo dokuzui. English Description: Berkeley, CA : Counterpoint Press, [2017] Identifiers: LCCN 2017007544 | ISBN 9781619029316 (hardcover) Subjects: LCSH: Zen Buddhism—Early works to 1800. Classification: LCC BQ9399.E594 K4513 2017 | DDC 294.3/927—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017007544 Jacket designed by Kelly Winton Book composition by VJB/Scribe COUNTERPOINT 2560 Ninth Street, Suite 318 Berkeley, CA 94710 www.counterpointpress.com Printed in the United States of America Distributed by Publishers Group West 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 To the Memory of R. H. Blyth CONTENTS Chronology of Hakuin’s Life Introduction BOOK ONE Instructions to the Assembly (Jishū) BOOK TWO Instructions to the Assembly (Jishū) (continued) General Discourses (Fusetsu) Verse Comments on Old Koans (Juko) Examining Old -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Soteriology in the Female

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Soteriology in the Female-Spirit Noh Plays of Konparu Zenchiku DISSERTATION submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSPHY in East Asian Languages and Literatures by Matthew Chudnow Dissertation Committee: Associate Professor Susan Blakeley Klein, Chair Professor Emerita Anne Walthall Professor Michael Fuller 2017 © 2017 Matthew Chudnow DEDICATION To my Grandmother and my friend Kristen オンバサラダルマキリソワカ Windows rattle with contempt, Peeling back a ring of dead roses. Soon it will rain blue landscapes, Leading us to suffocation. The walls structured high in a circle of oiled brick And legs of tin- Stonehenge tumbles. Rozz Williams Electra Descending ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iv CURRICULUM VITAE v ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION vi INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1: Soteriological Conflict and 14 Defining Female-Spirit Noh Plays CHAPTER 2: Combinatory Religious Systems and 32 Their Influence on Female-Spirit Noh CHAPTER 3: The Kōfukuji-Kasuga Complex- Institutional 61 History, the Daijōin Political Dispute and Its Impact on Zenchiku’s Patronage and Worldview CHAPTER 4: Stasis, Realization, and Ambiguity: The Dynamics 95 of Nyonin Jōbutsu in Yōkihi, Tamakazura, and Nonomiya CONCLUSION 155 BIBLIOGRAPHY 163 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation is the culmination of years of research supported by the department of East Asian Languages & Literatures at the University of California, Irvine. It would not have been possible without the support and dedication of a group of tireless individuals. I would like to acknowledge the University of California, Irvine’s School of Humanities support for my research through a Summer Dissertation Fellowship. I would also like to extend a special thanks to Professor Joan Piggot of the University of Southern California for facilitating my enrollment in sessions of her Summer Kanbun Workshop, which provided me with linguistic and research skills towards the completion of my dissertation. -

ELEMENTS of FICTION – NARRATOR / NARRATIVE VOICE Fundamental Literary Terms That Indentify Components of Narratives “Fiction

Dr. Hallett ELEMENTS OF FICTION – NARRATOR / NARRATIVE VOICE Fundamental Literary Terms that Indentify Components of Narratives “Fiction” is defined as any imaginative re-creation of life in prose narrative form. All fiction is a falsehood of sorts because it relates events that never actually happened to people (characters) who never existed, at least not in the manner portrayed in the stories. However, fiction writers aim at creating “legitimate untruths,” since they seek to demonstrate meaningful insights into the human condition. Therefore, fiction is “untrue” in the absolute sense, but true in the universal sense. Critical Thinking – analysis of any work of literature – requires a thorough investigation of the “who, where, when, what, why, etc.” of the work. Narrator / Narrative Voice Guiding Question: Who is telling the story? …What is the … Narrative Point of View is the perspective from which the events in the story are observed and recounted. To determine the point of view, identify who is telling the story, that is, the viewer through whose eyes the readers see the action (the narrator). Consider these aspects: A. Pronoun p-o-v: First (I, We)/Second (You)/Third Person narrator (He, She, It, They] B. Narrator’s degree of Omniscience [Full, Limited, Partial, None]* C. Narrator’s degree of Objectivity [Complete, None, Some (Editorial?), Ironic]* D. Narrator’s “Un/Reliability” * The Third Person (therefore, apparently Objective) Totally Omniscient (fly-on-the-wall) Narrator is the classic narrative point of view through which a disembodied narrative voice (not that of a participant in the events) knows everything (omniscient) recounts the events, introduces the characters, reports dialogue and thoughts, and all details. -

NWS Foreshadowing Interview

The Foreshadowing Marcus Sedgwick The Foreshadowing I know you have been interested in the Cassandra myth for some time; can you tell us how it came to form the basis of The Foreshadowing? Cassandra has about four one-line mentions in Homer’s Iliad. Most of her story is in Aeschylus’ Agamemnon, which was my main source, though I did read some of the things that have been written about her as well. Apollo gave Cassandra the gift of the prophecy but then cursed her so that so no one would believe that her visions were true – at least that’s one version of the story. It’s interesting because although people are aware of her story, she’s not a central character in the Trojan Wars. I think that’s because of her curse which I think is a powerful story and one that I have wanted to use for a while. In the end I didn’t need much of the original myth and quickly moved into my own story. By setting the book in the First World War, I was able to give it more layers, whereas a straight retelling of Greek myth would have been more limited. I used the parallels with the original story where they fitted my purpose; for example, their sea journeys and the war. However, I tried not to swamp my story with original source material. And there is a point of departure from the original when Alexandra eventually frees herself with her belief that she can’t make her own future. -

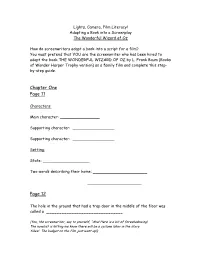

Chapter One Page 11 Page 12

Lights, Camera, Film Literacy! Adapting a Book into a Screenplay The Wonderful Wizard of Oz How do screenwriters adapt a book into a script for a film? You must pretend that YOU are the screenwriter who has been hired to adapt the book THE WONDERFUL WIZARD OF OZ by L. Frank Baum (Books of Wonder Harper Trophy version) as a family film and complete this step- by-step guide. Chapter One Page 11 Characters: Main character: ________________ Supporting character: _________________ Supporting character: _________________ Setting: State: ___________________ Two words describing their home: ______________________ ______________________ Page 12 The hole in the ground that had a trap door in the middle of the floor was called a _______________________________ (You, the screenwriter, say to yourself, “Aha! Here is a bit of foreshadowing! The novelist is letting me know there will be a cyclone later in the story. Yikes! The budget on the film just went up!) Pages 13 & 14 - a picture page. Page 15 As Aunt Em has been described on pages 12 & 13, would you write funny lines or serious lines of dialogue for her? _____________________ Based on the novelist’s descriptions of Aunt Em and Uncle Henry, who would get more lines of dialogue? _______________________ (“Uh, oh…the director has to work with a dog.”) The story opens with the family worried about ___________________. Pages 16, 17, 18 (“Yep…The cyclone. “) Look at your LCL! 3x3 Story Path Act I. (“Wait,” you say. These steps have hardly been developed at all. In the script, I must add more. I’m not sure what yet, but as I read on, I will look for ideas.”) Chapter Two Pages 19 & 20 - a picture page. -

Presenting Foreshadowing

Presenting Foreshadowing Monica Callahan Have you ever finished watching a movie and said “I saw that coming”? Those feelings of “I knew it” or “the clues were right there” are examples of the ways foreshadowing plays out in a film. When a director uses the technique of foreshadowing, the audience is given direct or subtle clues about what will happen. “Foreshadowing is a literary tool authors and film makers adapt to provide early clues about where the plot is headed.”1 My goal for this unit is that my third grade students will be able to recognize foreshadowing in a film and eventually in a written text. I also want my students to be able to produce written pieces that use foreshadowing. Introduction I teach third grade at McVey Elementary School in the Christina School District. McVey Elementary School is made up of approximately 440 students, 50% of whom are low income. Approximately 43% of our students are African American, while 40% are Caucasian. The district includes a section of Wilmington, Delaware’s largest city, and the city of Newark, some 14 miles to the west. There are three high schools, four middle schools and 18 elementary schools. The elementary schools are configured K-5. McVey Elementary School is situated among a quiet community of small detached homes in Newark just off the I-95 corridor and within a mile of the University of Delaware main campus. The 2016-2017 school year will be my first in regular education. I have previously taught Special Education to students with intense behavioral needs. -

Attention, Representation, and Unsettlement in Katherena Vermette's the Break, Or, Teaching

humanities Article Attention, Representation, and Unsettlement in Katherena Vermette’s The Break, or, Teaching and (Re)Learning the Ethics of Reading Cynthia R. Wallace Department of English, St. Thomas More College, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, SK S7N 0W6, Canada; [email protected] Received: 24 July 2019; Accepted: 11 October 2019; Published: 16 October 2019 Abstract: Theories of literary ethics often emphasize either content or the structural relationship between text and reader, and they tend to bracket pedagogy. This essay advocates instead for an approach that sees literary representation and readerly attention as interanimating and that considers teaching an important aspect of an ethics of reading. To support these positions, I turn to Katherena Vermette’s 2016 novel The Break, which both represents the urgent injustice of sexualized violence against Indigenous women and girls and also metafictionally comments on the ethics of witnessing. Describing how I read with my students the novel’s insistent thematization of face-to-face encounters and practices of attention as an invitation to read with Emmanuel Levinas and Simone Weil, I explicate the text’s self-aware commentary on both the need for readers to resist self-enlargement in their encounters with others’ stories and also the danger of generalizing readerly responsibility or losing sight of the material realities the text represents. I source these challenges both in the novel and in my students’ multiple particularities as readers facing the textual other. Ultimately, the essay argues for a more careful attention to which works we bring into our theorizing of literary ethics, and which theoretical frames we bring into classroom conversations.