Download (2MB)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Liverpool Development Update

LIVERPOOL DEVELOPMENT UPDATE November 2016 Welcome Welcome to the latest edition of Liverpool Development Update. When I became Mayor of the city in 2012, I said that Liverpool’s best days were ahead of it. If you consider the levels of investment being seen across the city today in 2016, my prediction is now ringing true. Since the start of 2012, we have seen over £3.8 billion worth of investment which has brought new businesses, new homes, new schools, and new and improved community and health facilities to Liverpool. We have seen the creation of nearly 15,000 job spaces, many of which will be filled with new jobs to the city. We have also created thousands more construction jobs. There is more good news. Several major new schemes are now in delivery mode. I am pleased to see rapid progress on Derwent’s Liverpool Shopping Park at Edge Lane, whilst Project Jennifer is now well underway with construction about to commence on its new Sainsburys and B&M stores. In addition, Neptune Developments have started work on the Lime Street Gateway project, and I can also report that work is underway on the first phase of the Welsh Streets scheme that will now see many of the traditional terraces converted to larger family homes. Meanwhile, some of the new schemes have started under the Strategic Housing Delivery Partnership which will build a further 1,500 new homes and refurbish another 1,000 existing ones. Plans for new schemes continue to be announced. The Knowledge Quarter is to be expanded with a new £1billion campus specialising in FRONT COVER: research establishments, whilst we are now also seeking to expand the Commercial Office District with new Grade A office space at Pall Mall which this city so vitally needs. -

HUNTS CROSS RETAIL PARK | Speke, Liverpool L24 9GB

Open A1 Retail Park Investment HUNTS CROSS RETAIL PARK | Speke, Liverpool L24 9GB ENTER Open A1 Retail Park Investment HUNTS CROSS RETAIL PARK | Speke, Liverpool L24 9GB Investment Considerations > Liverpool is one of the largest > The scheme has an open A1 non- cities in the UK and is a major food planning consent. retail destination. > The total rent is £701,144 per > The subject property is situated annum equating to low rents in a highly accessible location, off averaging £10 per sq ft. the A562, the main arterial route connectingSpeketothecitycentre. > We are instructed to seek offers for the long leasehold interest in > The scheme sits adjacent to the above property based on an Hunts Cross Shopping Centre, attractive net initial yield of 8% anchored by a dominant ASDA. (assuming purchaser’s costs of 5.80%). This equates to a > The scheme totals 70,973 sq ft purchase price of £8,284,000 with demised car parking for 222 (Eight Million,Two Hundred and vehicles. Eighty FourThousand Pounds), > The property is held on a subject to contract and exclusive headlease with 946 years of VAT. unexpired at a peppercorn. > The property benefits from a long average income weighted unexpired lease term of 9.6 years, let to Matalan, Poundstretcher, Xercise4Less and Next. Investment Location Catchment Population Situation & Description Tenancies, Tenure and Asset Management & VAT, Proposal & Considerations & Retail Warehousing Title & Planning Tenants’ Covenants Contacts < > in Liverpool B Oldham M58 M61 M6 Open A1 Retail Park Investment MANCHESTER HUNTS CROSS RETAIL PARK | Speke, Liverpool L24 9GB A580 A580 St. Helens M60 M57 M62 Bootle M60 Sale M62 A57 LIVERPOOL HUNTS CROSS Warrington Stockport RETAIL PARK A557 Location Widnes M56 M53 Liverpool is the 6th largest city in the UK, a major regional centre and the Speke Runcorn principal retail focus for the metropolitan county of Merseyside. -

Engagement & Involvement Group Notes

NOTES Engagement and Involvement Group (E&I) Committee Room 1, Runcorn Town Hall Monday 11 November 2019 13:30-15:30 In attendance: Stacy Evans (Halton CCG), Diane McCormick (PPG+ and Halton Peoples Health Forum), , Michelle Osborne (HBC), Lorna Plumpton (PPG), Des Chow (Halton CCG- acting chair), Ruth Austin-Vincent (GB member Halton CCG), Helen Monaghan (Halton CCG), Nicola Goodwin (HBC) Apologies: Maria Austin (Warrington and Halton CCG), Tracy Tilston (Nightstop communities), Matt Roberts (VSCA), Alec Schofield (Halton CCG), Richard Ashworth (Halton OPEN), Lisa Taylor (HBC), Angela Green (Bridgewater), David Derefaka (SHAP ltd), Sophie Bartsch (One Halton project manager), Phil McClure (Young Addaction Halton). No Agenda Notes Item Welcome Welcomed members to the meeting and introductions took place. 1 and Introductions 2 Minutes of Stacey Evans gave her apologies for last month and will be added under apologies. the last Minutes have been approved by the group. meeting and Please send any specific issues and actions to [email protected] before the next actions meeting takes place. Actions completed:- 1) Samantha Whelan has gone on the distribution list. 2) More communication is needed to highlight the importance of the flu jab for pregnant women. Lisa Taylor was absent to be discussed next month. 3) Richard Ashworth linked in with finance team about costs per bed per night, cost of an ambulance and other NHS services. Action: Send round to all participants encouraging them to attend and/or send deputies as group is focused on engagement with CCG and One Halton work with a couple of actions discussed in this meeting that all members need to support. -

Multiple Group Description Trading Name Number and Street Name

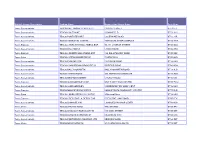

Multiple Group Description Trading Name Number And Street Name Post Code Tesco Supermarkets TESCO BALLYMONEY CASTLE ST CASTLE STREET BT53 6JT Tesco Supermarkets TESCO COLERAINE 2 BANNFIELD BT52 1HU Tesco Supermarkets TESCO PORTSTEWART COLERAINE ROAD BT55 7JR Tesco Supermarkets TESCO YORKGATE CENTRE YORKGATE SHOP COMPLEX BT15 1WA Tesco Express TESCO CHURCH ST BALLYMENA EXP 99-111 CHURCH STREET BT43 8DG Tesco Supermarkets TESCO BALLYMENA LARNE ROAD BT42 3HB Tesco Express TESCO CARNINY BALLYMENA EXP 144 BALLYMONEY ROAD BT43 5BZ Tesco Extra TESCO ANTRIM MASSEREENE CASTLEWAY BT41 4AB Tesco Supermarkets TESCO ENNISKILLEN 11 DUBLIN ROAD BT74 6HN Tesco Supermarkets TESCO COOKSTOWN BROADFIELD ORRITOR ROAD BT80 8BH Tesco Supermarkets TESCO BALLYGOMARTIN BALLYGOMARTIN ROAD BT13 3LD Tesco Supermarkets TESCO ANTRIM ROAD 405 ANTRIM RD STORE439 BT15 3BG Tesco Supermarkets TESCO NEWTOWNABBEY CHURCH ROAD BT36 6YJ Tesco Express TESCO GLENGORMLEY EXP UNIT 5 MAYFIELD CENTRE BT36 7WU Tesco Supermarkets TESCO GLENGORMLEY CARNMONEY RD SHOP CENT BT36 6HD Tesco Express TESCO MONKSTOWN EXPRES MONKSTOWN COMMUNITY CENTRE BT37 0LG Tesco Extra TESCO CARRICKFERGUS CASTLE 8 Minorca Place BT38 8AU Tesco Express TESCO CRESCENT LK DERRY EXP CRESCENT LINK ROAD BT47 5FX Tesco Supermarkets TESCO LISNAGELVIN LISNAGELVIN SHOP CENTR BT47 6DA Tesco Metro TESCO STRAND ROAD THE STRAND BT48 7PY Tesco Supermarkets TESCO LIMAVADY ROEVALLEY NI 119 MAIN STREET BT49 0ET Tesco Supermarkets TESCO LURGAN CARNEGIE ST MILLENIUM WAY BT66 6AS Tesco Supermarkets TESCO PORTADOWN MEADOW CTR MEADOW -

At-Home COVID-19 Testing Kit (PCR)

We are busy updating our site to make it an even better experience for you. Normal service will resume on Sunday evening. In the meantime if you wish to purchase an At-home COVID-19 testing kit, then follow the instructions detailed below. If you wish to purchase an At-home COVID-19 testing kit you will need to do so in store during the period above. Please see the list of stores that stock this test kit at the bottom of this document. MyHealthChecked At-home COVID-19 PCR test What is a MyHealthChecked At-Home COVID-19 PCR Swab Test? The MyHealthChecked At-home COVID-19 PCR test is an easy to use, nasal self-swab test to help identify if you have the COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2) virus. This test can be used for both general testing and international travel, where a Fit to Fly certificate is required. You must check with your travel provider exactly what your requirements are before ordering, as requirements and timings can vary greatly from country to country. The test is also suitable for individuals prior to making decisions such as travel or meeting with friends or family, or someone who needs to prove a negative test result for group attendance. Who is this test suitable for? The MyHealthChecked At-home COVID-19 PCR test is suitable for all ages and can be used by both adults and children. Adults aged 18 and over: self-test (unless unable to do so). Children and teenagers aged 12 to 17: self-test with adult supervision. -

Collection List 2021.Xlsx

AccNoPrefix No Description 1982 1 Shovel used at T Bolton and Sons Ltd. 1982 2 Shovel used at T Bolton and Sons Ltd STENCILLED SIGNAGE 1982 3 Telegraph key used at T Bolton and Sons Ltd 1982 4 Voltmeter used at T Bolton and Sons Ltd 1982 5 Resistor used at T Bolton and Sons Ltd 1982 6 Photograph of Copper Sulphate plant at T Bolton and Sons Ltd 1982 7 Stoneware Jar 9" x 6"dia marked 'Imperial Chemical Industries Ltd General Chemicals Division' 1982 8 Stoneware Jar 11" x 5"dia marked 'Cowburns Botanical Beverages Heely Street Wigan 1939' 1982 9 Glass Carboy for storing hydrochloric acid 1982 10 Bar of 'Bodyguard' soap Gossage and Sons Ltd Leeds 1982 11 Pack of Gossages Tap Water Softener and Bleacher 1982 12 Wall Map Business Map of Widnes 1904 1982 13 Glass Photo Plate Girl seated at machine tool 1982 14 Glass Photo Plate W J Bush and Co Exhibition stand 1982 15 Glass Photo Plate H T Watson Ltd Exhibition stand 1982 16 Glass Photo Plate Southerns Ltd Exhibition stand 1982 17 Glass Photo Plate Fisons Ltd Exhibition stand 1982 18 Glass Photo Plate Albright and Wilson Exhibition stand 1982 19 Glass Photo Plate General view of Exhibition 1982 20 Glass Photo Plate J H Dennis and Co Exhibition stand 1982 21 Glass Photo Plate Albright and Wilson Chemicals display 1982 22 Glass Photo Plate Widnes Foundry Exhibition stand 1982 23 Glass Photo Plate Thomas Bolton and Sons Exhibition stand 1982 24 Glass Photo Plate Albright and Wilson Exhibition stand 1982 25 Glass Photo Plate Albright and Wilson Exhibition stand 1982 26 Glass Photo Plate 6 men posed -

Halton Local Plan 2014-2037 May 2019

Halton Local Plan 2014-2037 Delivery and Allocations Local Plan (incorporating Partial Review of the Core Strategy) (Regulation 19) Proposed Submission Draft May 2019 Halton Delivery and Allocations Local Plan 2018-38 Proposed Submission Draft 2019 FOREWORD I would like to thank you for taking the time to take part in this consultation on Halton Borough Council’s Local Plan. This document builds upon and supports the sustainable growth strategy for the area set out in the adopted Core Strategy. It includes consultation on the Revised Core Strategy policies and the Delivery and Allocations Local Plan. This document will seek to find and allocate the most sustainable sites to provide new housing and jobs, without these our local economy cannot grow and prosper and without the right infrastructure of all types to support that growth, our communities will not thrive. Because of this, the plan is about more than just finding sites to build on. It is also about identifying where building shouldn’t happen at all or where particular care must be taken. Its policies protect what is important to local people such as parks and playing pitches, Conservation Areas and Local Wildlife Sites. The development management policies need to be flexible enough to respond to legislative and market changes, whilst allowing the Council to strive for excellence in all development that arises from the proposals it makes decisions upon. Cllr Hignett iii Halton Delivery and Allocations Local Plan 2018-38 Proposed Submission Draft 2019 CONTENTS FOREWORD ........................................................................................................................................... -

Our Strategy Will Benefit from a Blend of Local, Regional and National Solutions That Are Able to Talk to Each Other Securely, Are Safe and Upgradable

/WarringtonAndHaltonHospitalsNHSFoundationTrust/ @WHHNHS O u r S t r a t e g y 2018 - 2023 Our mission is to be OUTSTANDING for our patients, our communities and each other. Our Mis Page 04 Our Mis, Vis, Val, Aim an Obet Page 05 Abo W Page 06-07 Cont - The Chan Hel Lanc Page 08-09 Delin or Qul Obet Page 10-11 Delin or Pep Obet Page 12-13 Delin or Susaby Obet Page 14-15 Clil Stag an Sers Page 16 How or Mis is be aced Page 17 Enan Stage Page 18-22 How we go he - Enam to da Page 23 Our sat in ac Page 24 2 Cont 3 Our Mis We will be OUTSTANDING for our patients, our communities and each other. Ste Mcu Mel Pic Chairman CBE DL Chief Executive In order to realise this goal, we recognise that we need the engagement and collaboration of our staff, our patients and local population and our partners across the health and care system. We commit to: Always put our patients first through high quality, safe care and an excellent patient experience Be the best place to work with a diverse, engaged workforce that is fit for the future Work in partnership to design and provide high quality, financially sustainable services in innovative and modern buildings We believe WHH has a strong future as part of a progressive local integrated health and care system with new hospital estate at the heart and a focus on supporting our populations to live long and healthy lives independently. Internally, our focus firmly remains on continually improving the quality of our care, embracing new ways of working and developing and empowering our staff to lead change and improvement. -

Wavertree Boulevard South Wavertree Techpark

WAVERTREE TECHPARK LIVERPOOL WAVERTREE BOULEVARD SOUTH WAVERTREE TECHPARK HOME EMAIL SAVE PRINT CLOSE HOME EMAIL SAVE PRINT CLOSE HOME EMAIL SAVE PRINT CLOSE WAVERTREE MODERN OFFICE SPACE TO LET FROM 500 TO 3,500 SQ FT TECHPARK WAVERTREE TECHPARK HOME EMAIL SAVE PRINT CLOSE HOME EMAIL SAVE PRINT CLOSE HOME EMAIL SAVE PRINT CLOSE ALL UNITS HAVE WAVERTREE Self-contained P Ample parking available TECHPARK Offices are well provided with natural light via P Secure site via barrier system P extensive glazing Suitable for a number of uses subject to Flexible business units P planning P WAVERTREECURRENT AVAILABILITY WAVERTREE BOULEV TECHPARKUNIT SQ M SQ FT ARD 1F 40.7 438 P UNIT 1 2C 41.7 449 A F/G 2D/E 307 3,305 D H B C E F G 3B 152.9 1,646 A B 3C 153 1,649 WAVERTREE BOULEVARD SOUTH E AD C UNIT 2 3E 41.7 449 D/E 3F 89.2 961 D HOME EMAIL SAVE PRINT CLOSE RO DRYDEN 4E 181 1,950 A-C F 4F 181 1,950 UNIT 4 F E D C B A G UNIT 3 HOME EMAIL SAVE PRINT CLOSE NUE WAVERTREE AVE HOME EMAIL SAVE PRINT CLOSE WAVERTREE AY KINGSW TUNNEL TECHPARK BA A5049 TH ST TH T ROAD T LEEDS ST PRESCO ’S S CENTRAL D BUSINES AL DISTRICT ON GTON NEW ISLINGT KENSIN TO M62 MOTORWAY> ST CHU T STREET S RCHILL WA PRESCO ST OSW Y EDGE LANE H TITHEBARN LIVERPOOL WAVERTREE EDGE LANE LIVERPOOL SHOPPING PARK PEMBROKE PLACEUNIVERSITY HOSPITAL EDGE LANE LIVERPOOL MILL LA INNOVATION DALE ST PARK BINNS RD RIA ST LIME ST TECHPARK A5080 TO N LIME STREET EDGE LANE DRYDEN RD KNOWLEDGE QUARTER PIGHUE LANE E VIC QUEENS DRIV STATION LITTLEWOODS VD FILM STUDIOS NEWTON CT A5080 MANCHESTER> OW HILL -

Liverpool Biennial 2018

BIENNIAL PARTNER EXHIBITION EXHIBITIONS Liverpool 1 9 WORLDS WITHIN 21 Tate Liverpool LJMU’s Exhibition WORLDS John Moores Royal Albert Dock, Research Lab Painting Prize 2018 Liverpool Waterfront LJMU’s John Lennon Some of these sites Walker Art Gallery L3 4BB Art & Design Building are open at irregular William Brown Street Biennial Duckinfield Street times or for special L3 8EL 2 L3 5RD events only. Refer to Open Eye Gallery p.37 for details. 23 19 Mann Island, 10 Bloomberg New Liverpool Waterfront Blackburne House 7 Contemporaries 2018 2018 L3 1BP Blackburne Place St George’s Hall LJMU’s John Lennon L8 7PE St George’s Place Art & Design Building 3 L1 1JJ Duckinfield Street RIBA North – National 11 L3 5RD Architecture Centre The Oratory 8 21 Mann Island, St James Mt L1 7AZ Victoria Gallery 24 Liverpool Waterfront & Museum This is Shanghai L3 1BP 12 Ashton Street, Mann Island & Liverpool University of The Cunard Building 4 Metropolitan Liverpool L3 5RF Liverpool Waterfront Bluecoat Cathedral Plateau School Lane L1 3BX Mount Pleasant 17 L3 5TQ Chalybeate Spring EXISTING 5 St James’ Gardens COMMISSIONS FACT 13 L1 7A Z 88 Wood Street Resilience Garden L1 4DQ 75–77 Granby Street 18 25 L8 2TX Town Hall Mersey Ferries 6 (Open Saturdays only) High Street L2 3SW Terminal The Playhouse Pier Head, Georges Theatre 14 19 Parade L3 1DP Williamson Square Invisible Wind Central Library L1 1EL Factory William Brown Street 26 (until 7 October) 3 Regent Road L3 8EW George’s Dock L3 7DS Ventilation Tower 7 20 George’s Dock Way St George’s Hall 15 World -

London Borough of Lambeth Retail and Town Centre Needs

London Borough of Lambeth Retail and Town Centre Needs Assessment London Borough of Lambeth 1 March 2013 11482/02/PW/PW This document is formatted for double sided printing. © Nathaniel Lichfield & Partners Ltd 2012. Trading as Nathaniel Lichfield & Partners. All Rights Reserved. Registered Office: 14 Regent's Wharf All Saints Street London N1 9RL All plans within this document produced by NLP are based upon Ordnance Survey mapping with the permission of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. © Crown Copyright reserved. Licence number AL50684A Retail & Town Centre Needs Assessment : London Borough of Lambeth Contents 1.0 Introduction 3 2.0 The Shopping Hierarchy 4 Centres in Lambeth and the Surrounding Area ..............................................4 Analysis of the Main Centres in Lambeth......................................................7 3.0 Assessment of Retail Needs 13 Introduction.............................................................................................13 Retail Trends ...........................................................................................13 Population and Expenditure.......................................................................20 Existing Retail Floorspace 2012 ................................................................20 Existing Spending Patterns 2012...............................................................21 Quantitative Capacity for Convenience Floorspace .......................................22 Quantitative Capacity for Comparison Floorspace ........................................24 -

Race and Radicalisation EJ Peatfield University of Liverpool

Race and Radicalisation E J Peatfield University of Liverpool Race and Radicalisation: Examining Perceptions Of Counter-Radicalisation Policy Amongst Minority Groups in Liverpool 8 and 24. Thesis submitted in accordance with the requirements of the University of Liverpool for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy by Elizabeth-Jane Peatfield February 2017 1 | Page Race and Radicalisation E J Peatfield University of Liverpool Abstract This thesis critically analyses the UK Government’s current counter-radicalisation policy, focusing in particular on groups presented as vulnerable or susceptible to the drivers of radicalisation outlined within the counter-radicalisation policy Prevent (2011). Although there have been a number of studies looking at the effect of counter-radicalisation policy on Muslim communities in Britain, this study is unique in its kind, as it examines the impact of counter-radicalisation policy on non- Muslim minorities. This work draws attention to the linking of terrorism to socio- economically marginalised groups and the concomitant gaze of surveillance or suspicion directed towards those considered risky. Based on the evidence gathered, it is argued that the negative framing of communities based on race and class has linked them to the risk of radicalisation through the construction of counter- radicalisation drivers and vulnerabilities. To explore the intersectionality of race and class with assumptions embedded in counter-radicalisation policy, the research employed both quantitative and qualitative methodology to examinee minority communities in two areas of Liverpool. The research sought to gauge how much non-Muslim minorities knew about Prevent (2011) and the drivers identified in the document, alongside whether they believed they had been affected by counter-radicalisation/terrorism policy.