Sant Tukaram.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lesson. 8 Devotional Paths to the Divine

Grade VII Lesson. 8 Devotional paths to the Divine History I Multiple choice questions 1. Religious biographies are called: a. Autobiography b. Photography c. Hierography d. Hagiography 2. Sufis were __________ mystics: a. Hindu b. Muslim c. Buddha d. None of these 3. Mirabai became the disciple of: a. Tulsidas b. Ravidas c. Narsi Mehta d. Surdas 4. Surdas was an ardent devotee of: a. Vishnu b. Krishna c. Shiva d. Durga 5. Baba Guru Nanak born at: a. Varanasi b. Talwandi c. Ajmer d. Agra 6. Whose songs become popular in Rajasthan and Gujarat? a. Surdas b. Tulsidas c. Guru Nanak d. Mira Bai 7. Vitthala is a form of: a. Shiva b. Vishnu c. Krishna d. Ganesha 8. Script introduced by Guru Nanak: a. Gurudwara b. Langar c. Gurmukhi d. None of these 9. The Islam scholar developed a holy law called: a. Shariat b. Jannat c. Haj d. Qayamat 10. As per the Islamic tradition the day of judgement is known as: a. Haj b. Mecca c. Jannat d. Qayamat 11. House of rest for travellers kept by a religious order is: a. Fable b. Sama c. Hospice d. Raqas 12. Tulsidas’s composition Ramcharitmanas is written in: a. Hindi b. Awadhi c. Sanskrit d. None of these 1 Created by Pinkz 13. The disciples in Sufi system were called: a. Shishya b. Nayanars c. Alvars d. Murids 14. Who rewrote the Gita in Marathi? a. Saint Janeshwara b. Chaitanya c. Virashaiva d. Basavanna 1. (d) 2. (b) 3. (b) 4. (b) 5. (b) 6. (d) 7. -

Secrets of RSS

Secrets of RSS DEMYSTIFYING THE SANGH (The Largest Indian NGO in the World) by Ratan Sharda © Ratan Sharda E-book of second edition released May, 2015 Ratan Sharda, Mumbai, India Email:[email protected]; [email protected] License Notes This ebook is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. This ebook may not be re-soldor given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person,please purchase an additional copy for each recipient. If you’re reading this book and didnot purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, then please return to yourfavorite ebook retailer and purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting the hardwork of this author. About the Book Narendra Modi, the present Prime Minister of India, is a true blue RSS (Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh or National Volunteers Organization) swayamsevak or volunteer. More importantly, he is a product of prachaarak system, a unique institution of RSS. More than his election campaigns, his conduct after becoming the Prime Minister really tells us how a responsible RSS worker and prachaarak responds to any responsibility he is entrusted with. His rise is also illustrative example of submission by author in this book that RSS has been able to design a system that can create ‘extraordinary achievers out of ordinary people’. When the first edition of Secrets of RSS was released, air was thick with motivated propaganda about ‘Saffron terror’ and RSS was the favourite whipping boy as the face of ‘Hindu fascism’. Now as the second edition is ready for release, environment has transformed radically. -

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email id Remarks 20001 MUDKONDWAR SHRUTIKA HOSPITAL, TAHSIL Male 9420020369 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PRASHANT NAMDEORAO OFFICE ROAD, AT/P/TAL- GEORAI, 431127 BEED Maharashtra 20002 RADHIKA BABURAJ FLAT NO.10-E, ABAD MAINE Female 9886745848 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PLAZA OPP.CMFRI, MARINE 8281300696 DRIVE, KOCHI, KERALA 682018 Kerela 20003 KULKARNI VAISHALI HARISH CHANDRA RESEARCH Female 0532 2274022 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 MADHUKAR INSTITUTE, CHHATNAG ROAD, 8874709114 JHUSI, ALLAHABAD 211019 ALLAHABAD Uttar Pradesh 20004 BICHU VAISHALI 6, KOLABA HOUSE, BPT OFFICENT Female 022 22182011 / NOT RENEW SHRIRANG QUARTERS, DUMYANE RD., 9819791683 COLABA 400005 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20005 DOSHI DOLLY MAHENDRA 7-A, PUTLIBAI BHAVAN, ZAVER Female 9892399719 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 ROAD, MULUND (W) 400080 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20006 PRABHU SAYALI GAJANAN F1,CHINTAMANI PLAZA, KUDAL Female 02362 223223 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 OPP POLICE STATION,MAIN ROAD 9422434365 KUDAL 416520 SINDHUDURG Maharashtra 20007 RUKADIKAR WAHEEDA 385/B, ALISHAN BUILDING, Female 9890346988 DR.NAUSHAD.INAMDAR@GMA RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 BABASAHEB MHAISAL VES, PANCHIL NAGAR, IL.COM MEHDHE PLOT- 13, MIRAJ 416410 SANGLI Maharashtra 20008 GHORPADE TEJAL A-7 / A-8, SHIVSHAKTI APT., Male 02312650525 / NOT RENEW CHANDRAHAS GIANT HOUSE, SARLAKSHAN 9226377667 PARK KOLHAPUR Maharashtra 20009 JAIN MAMTA -

403 Little Magazines in India and Emergence of Dalit

Volume: II, Issue: III ISSN: 2581-5628 An International Peer-Reviewed Open GAP INTERDISCIPLINARITIES - Access Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies LITTLE MAGAZINES IN INDIA AND EMERGENCE OF DALIT LITERATURE Dr. Preeti Oza St. Andrew‘s College Mumbai University [email protected] INTRODUCTION As encyclopaedia Britannica defines: ―Little Magazine is any of various small, usually avant-garde periodicals devoted to serious literary writings.‖ The name signifies most of all a usually non-commercial manner of editing, managing, and financing. They were published from 1880 through much of the 20th century and flourished in the U.S. and England, though French and German writers also benefited from them. HISTORY Literary magazines or ‗small magazines‘ are traced back in the UK since the 1800s. Americas had North American Review (founded in 1803) and the Yale Review(1819). In the 20th century: Poetry Magazine, published in Chicago from 1912, has grown to be one of the world‘s most well-regarded journals. The number of small magazines rapidly increased when the th independent Printing Press originated in the mid 20 century. Small magazines also encouraged substantial literary influence. It provided a very good space for the marginalised, the new and the uncommon. And that finally became the agenda of all small magazines, no matter where in the world they are published: To promote literature — in a broad, all- encompassing sense of the word — through poetry, short fiction, essays, book reviews, literary criticism and biographical profiles and interviews of authors. Little magazines heralded a change in literary sensibility and in the politics of literary taste. They also promoted alternative perspectives to politics, culture, and society. -

E-Digest on Ambedkar's Appropriation by Hindutva Ideology

Ambedkar’s Appropriation by Hindutva Ideology An E-Digest Compiled by Ram Puniyani (For Private Circulation) Center for Study of Society and Secularism & All India Secular Forum 602 & 603, New Silver Star, Behind BEST Bus Depot, Santacruz (E), Mumbai: - 400 055. E-mail: [email protected], www.csss-isla.com Page | 1 E-Digest - Ambedkar’s Appropriation by Hindutva Ideology Preface Many a debates are raging in various circles related to Ambedkar’s ideology. On one hand the RSS combine has been very active to prove that RSS ideology is close to Ambedkar’s ideology. In this direction RSS mouth pieces Organizer (English) and Panchjanya (Hindi) brought out special supplements on the occasion of anniversary of Ambedkar, praising him. This is very surprising as RSS is for Hindu nation while Ambedkar has pointed out that Hindu Raj will be the biggest calamity for dalits. The second debate is about Ambedkar-Gandhi. This came to forefront with Arundhati Roy’s introduction to Ambedkar’s ‘Annihilation of Caste’ published by Navayana. In her introduction ‘Doctor and the Saint’ Roy is critical of Gandhi’s various ideas. This digest brings together some of the essays and articles by various scholars-activists on the theme. Hope this will help us clarify the underlying issues. Ram Puniyani (All India Secular Forum) Mumbai June 2015 Page | 2 E-Digest - Ambedkar’s Appropriation by Hindutva Ideology Contents Page No. Section A Ambedkar’s Legacy and RSS Combine 1. Idolatry versus Ideology 05 By Divya Trivedi 2. Top RSS leader misquotes Ambedkar on Untouchability 09 By Vikas Pathak 3. -

List of Documentary Films Produced by Sahitya Akademi

Films Produced by Sahitya Akademi (Till Date) S.No. Author Directed by Duration 1. Amrita Pritam (Punjabi) Basu Bhattacharya 60 minutes 2. Akhtar-ul-Iman (Urdu) Saeed Mirza 60 minutes 3. V.K. Gokak (Kannada) Prasanna 60 minutes 4. Takazhi Sivasankara Pillai (Malayalam) M.T. Vasudevan Nair 60 minutes 5. Gopalkrishna Adiga (Kannada) Girish Karnad 60 minutes 6. Vishnu Prabhakar (Hindi) Padma Sachdev 60 minutes 7. Balamani Amma (Malayalam) Madhusudanan 27 minutes 8. Vinda Karandikar (Marathi) Nandan Kudhyadi 60 minutes 9. Annada Sankar Ray (Bengali) Budhadev Dasgupta 60 minutes 10. P.T. Narasimhachar (Kannada) Chandrasekhar Kambar 27 minutes 11. Baba Nagarjun (Hindi) Deepak Roy 27 minutes 12. Dharamvir Bharti (Hindi) Uday Prakash 27 minutes 13. D. Jayakanthan (Tamil) Sa. Kandasamy 27 minutes 14. Narayan Surve (Marathi) Dilip Chitre 27 minutes 15. Bhisham Sahni (Hindi) Nandan Kudhyadi 27 minutes 16. Subhash Mukhopadhyay (Bengali) Raja Sen 27 minutes 17. Tarashankar Bandhopadhyay (Bengali) Amiya Chattopadhyay 27 minutes 18. Vijaydan Detha (Rajasthani) Uday Prakash 27 minutes 19. Navakanta Barua (Assamese) Gautam Bora 27 minutes 20. Mulk Raj Anand (English) Suresh Kohli 27 minutes 21. Gopal Chhotray (Oriya) Jugal Debata 27 minutes 22. Qurratulain Hyder (Urdu) Mazhar Q. Kamran 27 minutes 23. U.R. Anantha Murthy (Kannada) Krishna Masadi 27 minutes 24. V.M. Basheer (Malayalam) M.A. Rahman 27 minutes 25. Rajendra Shah (Gujarati) Paresh Naik 27 minutes 26. Ale Ahmed Suroor (Urdu) Anwar Jamal 27 minutes 1 27. Trilochan Shastri (Hindi) Satya Prakash 27 minutes 28. Rehman Rahi (Kashmiri) M.K. Raina 27 minutes 29. Subramaniam Bharati (Tamil) Soudhamini 27 minutes 30. O.V. -

4.3 Dilip Chitre's Poem “Ode to Bombay”

Indian English Poetry UNIT 4 DILIP CHITRE AND KEKI N. DARUWALLA Structure 4.0 Objectives 4.1 Introduction 4.2 Dilip Chitre: An Introduction 4.3 Dilip Chitre’s Poem “Ode to Bombay” 4.4 Keki N. Daruwalla: An Introduction 4.5 Keki N. Daruwalla’s Poem “Chinar” 4.6 Let Us Sum Up 4.7 Questions 4.8 References 4.9 Suggested Readings 4.0 OBJECTIVES The unit is meant to acquaint you with the phenomenon of the 1980s and 90s in India’s cultural life in general and Indian poetry in particular. In the context, the poets analyzed in the present unit speak of the concerns of this era as life became increasingly opportunity-centric and literature looked inwards to point at its own incapacities. Dilip Chitre and Keki N. Daruwalla are the poets we shall be focusing upon in this unit. You would be able to notice in the poems analyzed here a shift in thematic concerns and change of the poetic style. Importantly, during the period, disillusionment among poets turned to cynicism as there was little that inspired writers. They took for expressing ordinary themes and wistfully looked at life. 4.1 INTRODUCTION As has been mentioned in the previous units, Indian English Poetry became more and more self-oriented in the post-Independence period. It turned to self- interrogation and focused on creating an identity for it, particularly distancing itself from the concerns of the poor and deprived. Indian English poetry tried to emulate the western literary trends and chose to merge with what was considered mainstream writing. -

53 Annual Report Colour Inner Final

SHIVAJI UNIVERSITY Estd : 1962 KOLHAPUR NAAC ‘A’ Grade MHRD-NIRF-28th Rank 53rd Annual Report : 2015-16 Shivaji University, Kolhapur 53rd Annual Report His Excellency Hon. Shri. Chennamaneni Vidyasagar Rao Chancellor Shivaji University, Kolhapur 53rd Annual Report Prof.(Dr.) Devanand Shinde Hon’ble Vice-Chancellor Shi v aji Uni v ersity , K olhapur 53 r d AnnualR Hon’ble Vice-Chancellor, Deans of Various Faculties, Hon. Director, B.C.U.D. Hon. Ag. Registrar, Hon. Controller of Examination, Hon. Ag. Finanace & Accounts Officer & Management Council with the Chief Guest of 52nd Convocation Ceremony Hon’ble Padmashri (Dr.) G. D. Yadav, Vice-Chancellor, Institute of Chemical Technology, Mumbai. eport Shivaji University, Kolhapur 53rd Annual Report The Book Procession at 52nd Convocation Ceremony Procession of 52nd Convocation Ceremony. Dignitaries inaugurating 52nd Convocation Ceremony Shivaji University, Kolhapur 53rd Annual Report Hon’ble Padmashri Prof. (Dr.) G.D. Yadav, Vice Chancellor, Institute of Chemical Technology, Mumbai, the Chief Guest of 52nd Convocation Ceremony being felicitated by Hon’ble Prof. Dr. Devanand Shinde Prof.(Dr.) Devanand Shinde, Vice-Chancellor speaking on the 52nd Convocation Ceremony. Smt. Priyanka Ramchandra Patil receiving President's Gold Medal for the year 2014-15 at the hands of the Chief Guest of 52nd Convocation Ceremony Hon’ble Padmashri Dr. G. D. Yadav, Vice-Chancellor, Institute of Chemical Technology, Mumbai. Shivaji University, Kolhapur 53rd Annual Report Smt. Madhavi Chandrakant Pandit, receiving Chancellor‘s Medal for the year 2014-15 at the hands of the Chief Guest of 52nd Convocation Ceremony Hon’ble Padmashri Dr. G. D. Yadav, Vice-Chancellor, Institute of Chemical Technology, Mumbai. -

Way of Life by Samartha Ramdas

Way of life by Samartha Ramdas In Maharashtra, the period between 12 th and 17 th century was the era of the famous saints, like Dnyaneshwar, Tukaram, Eknath, Namdeo, Samartha Ramdas, and, Meerabi, Kabir etc. in North India. These saints showed common people easy path to reach God, which is called Bhaktiyog. That path was Namasmaran, which ultimately merges into transcendental meditation! The continuous ‘Namasmaran’ leads you to the state of pure consciousness. The ‘Nama’ melts into your soul gradually and your mind becomes thoughtless. The regular practice of ‘Namasmaran’ prepares your mind to overcome the difficult situations, in your life and gives you courage and peace of mind. Actually, peace of mind is the true aim of our life. Isn’t it! That is according to Ramdas, ‘Moksha’ – salvation from worldly pains. For the attainment of this kind of salvation, you need not get rid of your five senses; because the body and the mind go hand in hand. You are very well supposed to fulfill the wishes of your five senses i.e. to see, listen, smell, test, and touch. You need not lead a life of an ascetic Samartha Ramdas (1608-1682) has written approximately 40,000 verses, a verse of four lines each, in different books. Karunshtake Ramdas left home when he was only twelve years old. Although he had strong control over his emotions, it was not easy to lead lonesome and hard life, during his self-training period. In that restless state of mind, Ramdas wrote Karunashtake. These are the prayers full of pathos or “Karuna rasa”. -

History and Political Science

The Coordination Committee formed by GR No. Abhyas - 2116/(Pra.Kra.43/16) SD - 4 Dated 25.4.2016 has given approval to prescribe this textbook in its meeting held on 29.12.2017 and it has been decided to implement it from the educational year 2018-19. HISTORY AND POLITICAL SCIENCE STANDARD TEN Maharashtra State Bureau of Textbook Production and Curriculum Research, Pune. The digital textbook can be obtained through DIKSHA App on a smartphone by using the Q. R. Code given on title page of the textbook and useful audio-visual teaching-learning material of the relevant lesson will be available through the Q. R. Code given in each lesson of this textbook. First Edition : 2018 © Maharashtra State Bureau of Textbook Production and Curriculum Reprint : Research, Pune - 411 004. The Maharashtra State Bureau of Textbook Production and Curriculum Research reserves October 2020 all rights relating to the book. No part of this book should be reproduced without the written permission of the Director, Maharashtra State Bureau of Textbook Production and Curriculum Research, ‘Balbharati’, Senapati Bapat Marg, Pune 411004. History Subject Committee Authors History Political Science Dr Sadanand More, Chairman Dr Shubhangana Atre Dr Vaibhavi Palsule Shri. Mohan Shete, Member Dr Ganesh Raut Shri. Pandurang Balkawade, Member Dr Shubhangana Atre, Member Translation Scrutiny Dr Somnath Rode, Member Shri. Bapusaheb Shinde, Member Dr Shubhangana Atre Dr Manjiri Bhalerao Dr Vaibhavi Palsule Dr Sanjot Apte Shri. Balkrishna Chopde, Member Shri. Prashant Sarudkar, Member Cover and Illustrations Shri. Mogal Jadhav, Member-Secretary Shri. Devdatta Prakash Balkawade Typesetting Civics Subject Committee DTP Section, Balbharati Dr Shrikant Paranjape, Chairman Paper Prof. -

RESUME Sachin Chandrakant Ketkar

1 RESUME Sachin Chandrakant Ketkar (Born 29 September 1972, Valsad, Gujarat, India 396 001) ● Associate Professor, Dept of English, Faculty of Arts, The MS University of Baroda, Baroda, Gujarat, India 2006- till date Academic Qualifications ● Ph.D. Veer Narmad South Gujarat University, Surat, Gujarat, India 2002 ‘Translation of Narsinh Mehta's Poems Into English: with a Critical Introduction' ● MA with English, First Class, The MS University of Baroda, Baroda, India, 1995 ● BA with English and Sanskrit, 58% , South Gujarat University, Surat, India, 1993 Professional experience ● Lecturer in English SB Garda College of Arts, PK Patel College of Commerce, Navasari, Gujarat, 1995- 2006 ● Visiting Post Graduate Teacher at Smt. JP Shroff Arts College, Valsad, India 1998-2006 Areas of Academic Interests Translation Studies, Comparative Literature, Literary Theory, Modernist Indian literature, Contemporary Marathi poetry, and English Language Teaching Publications Books 1. English for Academic Purposes-II, Co- authored with Dr. Deeptha Achar et. al . Ahmedabad: University Granth Nirman Board, 2011, ISBN 978938126-3 2. English for Academic Purposes-I, Co- authored with Dr. Deeptha Achar et. al . Ahmedabad: University Granth Nirman Board, Aug 2011, ISBN 938126512-7 3. Skin, Spam and Other Fake Encounters, Selected Marathi Poems in English translation, Mumbai: Poetrywala, August 2011, ISBN 61-89621-22-X 4. (Trans) Migrating Words: Refractions on Indian Translation Studies, VDM Verlag-1 Publishers, Oct 2010, ISBN 978-3-639-30280-6 5. Jarasandhachya Blog Varche Kahi Ansh, Abhidhanantar Prakashan , Mumbai, Marathi Poems, Jan 2010, ISBN 978-81-89621-15-5 6. Live Update: an Anthology of Recent Marathi Poetry , editor and translator, Poetrywala 2 Publications, Mumbai, July 2005 , ISBN 81-89621-00-9 7. -

03-Result Rollno

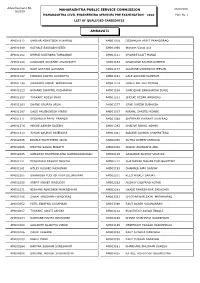

Advertisement No. MAHARASHTRA PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION 03/09/2021 6/2019 MAHARASHTRA CIVIL ENGINEERING SERVICES PRE EXAMINATION - 2020 Page No. 1 LIST OF QUALIFIED CANDIDATES AMRAVATI AM001012 UMEKAR ASHUTOSH VIJAYRAO AM001018 DESHMUKH ARPIT PRAMODRAO AM001080 KATHALE SAURABH NITIN AM001098 Wanode Vishal Anil AM001102 DHIRAJ RAJENDRA TAMGADGE AM001121 DHONDE LALIT MANOJ AM001128 GAWANDE SAURABH JAGANNATH AM001163 NAVDURGE SACHIN RAMESH AM001173 KALE GAYATRI GAJANAN AM001174 GULHANE VAISHNAVI JEEVAN AM001187 POOJARI KARTIK KURMAYYA AM001191 KALE SAURABH RAMESH AM001194 GAWANDE KOMAL WAMANRAO AM001214 UMALE PALLAVI TEJRAO AM001223 HUMANE SWAPNIL PUSHPARAJ AM001224 GHADEKAR SANGHARSH SUNIL AM001257 THAKARE ADESH RAJU AM001261 SHELKE KEDAR AMBADAS AM001264 DHANE GAURAV ARUN AM001277 GAYE JAYESH SUBHASH AM001297 GADE HRUSHIKESH VINOD AM001307 NIRMAL SHRITEJ ASHOK AM001311 DESHMUKH PAYAL PRAMOD AM001360 SHEREKAR VIKRANT VIJAYRAO AM001374 MEKHE ASHISH RAJESH AM001383 DHADVE NIKHIL ASHOK AM001413 JUWAR GAURAV RAJENDRA AM001431 BOKARE LAXMAN CHAMPATRAO AM002006 INGOLE PRATHMESH ARUN AM002050 SUYOG RAMESH BORKAR AM002065 BHOYAR SAGAR EKNATH AM002066 ADSOD AKANKSHA ANIL AM002085 KUMAWAT MUKESHKUMAR RAJENDRAPRASAD AM002100 GAWANDE AKSHAY VINAYAK AM002121 DESHMUKH RASHMI YOGESH AM002122 CHATARKAR MOHAN PURUSHOTTAM AM002141 HOLEY RUGVED RAJKUMAR AM002183 DHAMALE AJAY SANJAY AM002205 BHANGDIA YUDHISHTHIR DILIPKUMAR AM002231 KELO ANIKET SANJAY AM002255 ARBAT ANIKET WASUDEV AM002263 AKSHAY DILIPRAO KOTHE AM002271 NISHANE ABHISHEK PRAKASHRAO AM002281 UKADE