Desired Future Conditions for Southwestern Riparian Ecosystems

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

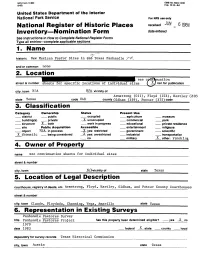

61934 Inventory Nomination Form Date Entered 1. Name 5. Location Of

NPS Form 10-900 0MB No. 1024-0018 (3-82) Exp. 10-31-84 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service For NPS use only National Register of Historic Places received JUN _ 61934 Inventory Nomination Form date entered See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type ail entries complete applicable sections _______________________________ 1. Name historic New Mexican Pastor Sites in this Texas Panhandle and/or common none 2. Location see c»nE*nuation street & number sheets for specific locations of individual sites ( XJ not for publication city, town vicinity of Armstrong (Oil), Floyd (153), Hartley (205 state Texas code 048 county Qldham (359), Potter (375) code______ Category Ownership Status Present Use district public occupied agriculture museum building(s) private X unoccupied commercial park structure X both work in progress educational private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious object N/A jn process X yes: restricted government scientific X thematic being considered X yes: unrestricted industrial transportation no military X other- ranrh-f-ng 4. Owner of Property name see continuation sheets for individual sites street & number city, town JI/Avicinity of state Texas 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Armstrong, Floyd, Hartley, Oldham, and Potter County Courthouses street & number city, town Claude, Floydada, Channing, Vega, Amarillo state Texas 6. Representation in Existing Surveys Panhandle Pastores Survey title Panhandle Pastores -

Eddy County Petroleum Industry Impact on New Mexico, 2012-2018

Eddy County Petroleum Industry Impact on New Mexico, 2012-2018 December 2019 Prepared by Dr. Kramer Winingham Arrowhead Center Brooke Montgomery Arrowhead Center Trashard Mays Arrowhead Center Chris Dunn Dunn Consulting Arrowhead Center New Mexico State University Las Cruces, NM 88003 arrowheadcenter.nmsu.edu Eddy County Petroleum Industry Impact on New Mexico, 2012-2018 December 2019 Prepared by Dr. Kramer Winingham Arrowhead Center Brooke Montgomery Arrowhead Center Trashard Mays Arrowhead Center Chris Dunn Dunn Consulting Arrowhead Center New Mexico State University Las Cruces, NM 88003 Please send comments or questions to [email protected] This page is left blank intentionally Executive Summary Eddy County New Mexico has contracted Arrowhead Center at New Mexico State University to prepare a study of the impacts of Eddy County’s petroleum industry1 on New Mexico from 2012-2018. Eddy County is currently experiencing a tremendous oil boom. New technology advances and discoveries have made land in this area part of the most attractive oil play in the world. For the first time since 1973, the United States has become the top oil producing nation in the world, driven by oil production in the Permian Basin.2 Recent assessments of oil and gas reserves in the Delaware Basin3 near Carlsbad, New Mexico have reported the largest continuous oil and gas resources ever discovered.4 These new discoveries and subsequent drilling have produced many benefits - increased employment, economic output, and government revenue. The purpose of this impact study is to attempt to quantify and estimate the impact of Eddy County’s petroleum industry on New Mexico from 2012-2018. -

Renewing the Creative Economy of New Mexico

Building on the Past, Facing the Future: Renewing the Creative Economy of New Mexico Jeffrey Mitchell And Gillian Joyce With Steven Hill And Ashley M. Hooper 2014 This report was commissioned by the New Mexico Department of Cultural Affairs and prepared by UNM’s Bureau of Business and Economic Research. As will be discussed in this report, we interviewed arts and culture workers and entrepreneurs across the state of New Mexico. We asked them for two words to describe New Mexico in general and for two words to describe how New Mexico has changed. We entered these data into a ’word cloud’ software program. The program visually represents the data so that the more often a word is mentioned, the larger it appears. The figure above is a representation of the words offered by members of the New Mexico creative economy when interviewed for this project. Acknowledgements We would like to thank Secretary Veronica Gonzales for her vision – without her, this project would not have been possible. Also, at the Department of Cultural Affairs we would like to thank Anne Green-Romig, Loie Fecteau and Paulius Narbutas for their support and patience. At the Department of Tourism, we would like to thank Jim Orr for his help with tourism data. We owe a debt of gratitude to the more than 200 arts and culture workers throughout the state who took time out of their days to offer their insights and experiences in the arts and culture industries of New Mexico. At UNM-BBER, we would like to thank Jessica Hitch for her intrepid data collection, Catherine A. -

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 065 384 SO 002 574 TITLE Outline of Content: Mexican American Studies. Grades INSTITUTION Los Angeles City Sc

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 065 384 SO 002 574 TITLE Outline of Content: Mexican American Studies. Grades 10-12. INSTITUTION Los Angeles City Schools, Calif. Div. of Instructional Planning and Services. PUB DATE 68 NOTE 57p. EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$3.29 DESCRIPTORS American History; *Cultural Awareness; Cultural Background; Curriculum Guides; Ethnic Groups; Ethnic Studies; *Mexican American History; *Mexican Americans; Minority Groups; Secondary Grades; *Social Studies Units; Spanish Americans; *United States History ABSTRACT An historical survey of Mexican Americans of the Southwest is outlined in this curriculum guide for high school students. The purpose of this course is to have students develop an appreciation for and an understanding of the role of the Mexican American in the development of the United States. Although the first half of the guide focuses upon the historical cultural background of Mexican Americans, the latter half emphases the culture conflict within the ethnic group and, moreover, their strnggle toward obtaining civil rights along with improvement of social and economic conditions. Five units are: 1) Spain in the New World; 2) The Collision of Two Cultures; 3) The Mexican American Heritage in the American Southwest; 4) A Sociological and Psychological View of the Mexican American; and 5) The Mexican American today. An appendix includes Mexican American winners of the Congressional Medal of Honor. Also included is a book and periodical bibliography. (SJM) -411 ' U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, EDUCATION S WELFARE OFFICE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRO- DUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIG- INATING IT. POINTS OF VIEW OR OPIN- IONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICE OF EDU- CATION POSITION OR POLICY. -

Cultural Resource Survey for the Lower Cow Creek Restoration Project, San Miguel County, New Mexico

CULTURAL RESOURCE SURVEY FOR THE LOWER COW CREEK RESTORATION PROJECT, SAN MIGUEL COUNTY, NEW MEXICO PREPARED FOR Pathfinder Environmental, LLC PREPARED BY Okun Consulting Solutions AUGUST 2018 Okun Consulting Solutions NMCRIS ACTIVITY NUMBER 141269 CULTURAL RESOURCE SURVEY FOR THE LOWER COW CREEK RESTORATION PROJECT, SAN MIGUEL COUNTY, NEW MEXICO Prepared for Pathfinder Environmental, LLC 1800 Old Pecos Trail, Suite E Santa Fe, NM 87505 Prepared and Submitted by Adam Okun, Principal Investigator Okun Consulting Solutions 441 Morningside Dr. NE Albuquerque, NM 87108 Reviewing Agencies United States Army Corps of Engineers New Mexico Historic Preservation Division Survey Conducted Under New Mexico General Archaeological Investigation Permit Number: NM-18-285-S Okun Consulting Report Number: OCS-2018-24 Okun Consulting Solutions LOWER COW CREEK RESTORATION PROJECT ABSTRACT The Upper Pecos Watershed Association is proposing a riparian restoration project along lower Cow Creek in San Miguel County, New Mexico. The project is approximately 0.75 miles long and is located less than 1 mile northwest of the town of North San Ysidro. Cow Creek is designated as a cold-water fishery, but water quality in the creek is currently impaired by high temperatures. The purpose of the proposed project is to reduce the water temperature in the creek, which is needed to support its designated use and improve riparian habitat. The project is being funded by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) through the Surface Water Bureau of the New Mexico Environment Department. It will take place entirely on private lands. A variety of restoration treatments are proposed, which will alleviate stream entrenchment and riverbank erosion and improve riparian habitat. -

Farmers, Hunters, and Colonists: Interaction Between the Southwest and the Southern Plains

Farmers, Hunters, and Colonists: Interaction Between the Southwest and the Southern Plains Item Type book; text Publisher University of Arizona Press (Tucson, AZ) Rights Copyright © 1991 by The Arizona Board of Regents. The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License (CC BY- NC-ND 4.0), https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Download date 11/10/2021 06:58:25 Item License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/632281 Interaction Between the Southwest and the Southern Plains Farmers, Hunters, and Colonists Farmers, Hunters, and Colonists INTERACTION BETWEEN THE SOUTHWEST AND THE SOUTHERN PLAINS Edited by Katherine A. Spielmann THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA PRESS TUCSON This Open Arizona edition is funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities/Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. The University of Arizona Press www.uapress.arizona.edu Copyright © 1991 by The Arizona Board of Regents Open-access edition published 2018 ISBN-13: 978-0-8165-3786-0 (open-access e-book) The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Typographical errors may have been introduced in the digitization process. The Library of Congress has cataloged the print edition as follows: Farmers, hunters, and colonists : interaction between the Southwest and the southern plains / edited by Katherine A. Spielmann. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. -

Ecology, Diversity, and Sustainability of the Middle Rio Grande Basin

This file was created by scanning the printed publication. Errors identified by the software have been corrected; however, some errors may remain. Chapter 3 Human Ecology and Ethnology Frank E. Wozniak, USDA Forest Service, Southwestern Regional Office, Albuquerque, New Mexico ies similar to that of de Buys (1985) on the Sangre de HISTORIC PERIODS Cristos would contribute significantly to our under Spanish Colonial A.D. 1540-1821 standing of the human role, human impacts, and Mexican A.D. 1821-1846 human relationships with the land, water, and other Territorial A.D. 1846-1912 resources of the Middle Rio Grande Basin during Statehood A.D. 1912-present historic times. Farming, ranching, hunting, mining, logging, and other human activities have signifi cantly affected Basin ecosystems in the last 450 years. Most of the research on resource availability and INTRODUCTION its role in regulating human impacts on the Basin has The relationship of humans with Middle Rio focused on the 20th century. Some work has been Grande Basin ecosystems is complex. In historic done on the second half of the 19th century but very times, humans had a critical role in the evolution of little on the 300 years of the historic era preceding environmental landscapes and ecosystems through the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848. This chap out the Middle Rio Grande Basin. The relationship ter summarizes the available historic information. of humans with the land is based on and regulated by resource availability, environmental conditions, OVERVIEW OF HUMAN IMPACTS levels of technological knowledge, political and so cioeconomic structures, and cultural values regard The principal factor influencing the human rela ing the use of land and water. -

The Metal Resources of New Mexico and Their Economic Features Through 1954

BULLETIN 39 The Metal Resources of New Mexico and Their Economic Features Through 1954 A revision of Bulletin 7, by Lasky and Wootton, with detailed information for the years 1932-1954 BY EUGENE CARTER ANDERSON 1957 STATE BUREAU OF MINES AND MINERAL RESOURCES NEW MEXICO INSTITUTE OF MINING & TECHNOLOGY CAMPUS STATION SOCORRO, NEW MEXICO NEW MEXICO INSTITUTE OF MINING & TECHNOLOGY E. J. Workman, President STATE BUREAU OF MINES AND MINERAL RESOURCES Alvin J. Thompson, Director THE REGENTS MEMBERS EX OFFICIO THE HONORABLE EDWIN L. MECHEM………...Governor of New Mexico MRS. GEORGIA L. LUSK ......................Superintendent of Public Instruction APPOINTED MEMBERS ROBERT W. BOTTS ....................................................................Albuquerque HOLM O. BURSUM, JR. .....................................................................Socorro THOMAS M. CRAMER .................................................................... Carlsbad JOHN N. MATHEWS, JR. ...................................................................Socorro RICHARD A. MATUSZESKI ......................................................Albuquerque Contents Page INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 1 Purpose and Scope of Bulletin ..................................................................................... 1 Other Reports Dealing With the Geology and Mineral Resources of New Mexico ...................................................................................................... -

El Camino Real De Tierra Adentro Archival Study

El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro As Revealed Through the Written Record: A Guide to Sources of Information for One of the Great Trails of North America Prepared for: The New Mexico Spaceport Authority (NMSA) Las Cruces and Truth or Consequences, New Mexico The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), Office of Commercial Space Transportation Compiled by: Jemez Mountains Research Center, LLC Santa Fe, New Mexico Contributors: Kristen Reynolds, Elizabeth A. Oster, Michael L. Elliott, David Reynolds, Maby Medrano Enríquez, and José Luis Punzo Díaz December, 2020 El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro As Revealed Through the Written Record: A Guide to Sources of Information for One of the Great Trails of North America Table of Contents 1. Introduction and Statement of Purpose .................................................................................................. 1 • Introduction .............................................................................................................................................. 1 • Scope and Organization ....................................................................................................................... 2 • El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro: Terminology and Nomenclature ............................... 4 2. History of El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro; National Historic Trail Status........................... 6 3. A Guide to Sources of Information for El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro .............................. 16 • 3.1. Archives and Repositories ....................................................................................................... -

Department of Cultural Affairs

NEW MEXICO DEPARTMENT OF CULTURAL AFFAIRS Economic and Rural Development Committee NOVEMBER 12, 2015 DCA research shows that on average, artists working on Public Art projects spend one third of the project budget in the local community where the artwork is installed. The Department of Cultural Affairs is New Mexico’s cultural steward—charged with preserving and showcasing the state’s cultural riches. With its eight museums, eight historic sites, arts, historic preservation, archaeology and library programs, New Mexico’s Department of Cultural Affairs is among the most ambitious and respected state cultural agencies in the nation. Together, the facilities, programs and services of the department see over 1.2 million visitors annually and help support a $5.6 billion cultural industry in New Mexico. The Department is divided into five programs and consists of 15 divisions. DCA owns and cares for 191 buildings with facilities on 16 campuses located throughout the state, and with programs and services reaching every county in New Mexico. The Department’s annual budget is approximately $42.4 million, of which $30.7 million is General Fund. 2 ART AND CULTURAL INDUSTRIES $5.6 billion Pump Into NM’s Economy 76,758 jobs Support 1 in 10 Jobs Statewide Impact $2.3 billion In Salaries And educate our kids to compete in the 21st century. 2014 UNM Bureau of Business & Economic Research Report “Building on the Past, Facing the Future: Renewing the Creative Economy of NM” commissioned by the NM Department of Cultural Affairs. 3 The 2015 International Folk Art Market had approximately 20,000 visitors during a single weekend and an estimated $11.3 million in economic impact to the state. -

Borderlands Wind Project Final Environmental Impact Statement

APPENDIX G: COMMENTS AND RESPONSES TO COMMENTS ON THE DRAFT EIS Borderlands Wind Project Final EIS and Proposed RMP Amendment March 2020 Appendix G: Comments and Responses to Comments on the Draft EIS Page Left Intentionally Blank Borderlands Wind Project Final EIS and Proposed RMP Amendment March 2020 Appendix G: Comments and Responses to Comments on the Draft EIS Table G-1. Comments and Responses to Comments on the Draft EIS Comment Comment on the Draft EIS Response to Comment ID 01.AS-1 I just wanted to say that what happens here in this county and in this small town with Thank you for your comment. It has been noted and will be this wind farm has an effect on Quay County in Tucumcari, New Mexico, specifically included in the administrative record for this EIS. Mesa Lands Community College. I teach wind technicians how to maintain turbines. And when there's a proposed wind farm, I generally get an influx of students from the surrounding high schools in my program. So it's a wonderful boon to our dying little town. There's a lot of dying little towns in New Mexico, and these projects really do boost our economy. And it's not just felt here locally around the local wind farm. It's felt in other places. I just wanted to make that known and that I really appreciate the consideration of the wind farm going in here. 01.MK-1 Generators, light towers, and other equipment powered by diesel, gasoline, or natural gas The construction contractor would ensure that all engines may require registration or an air quality permit if the emissions of any criteria generators, light towers and other equipment powered by air pollutant will exceed 10 pounds per hour and 10 tons per year. -

United States-Mexico Economic Relations Hearings

1liqz S. HRG. 100-424 UNITED STATES-MEXICO ECONOMIC RELATIONS HEARINGS BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON ECONOMIC RESOURCES AND COMPETITJNENESS OF THE JOINT ECONOMIC COMMITTEE CONGRESS OF THE UNITED STATES ONE HUNDREDTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION JUNE 12 AND 13, 1987 Printed for the use of the Joint Economic Committee U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 80-276 WASHINGTON: 1988 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, Congressional Sales Office U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC 20402 JOINT ECONOMIC COMMITTEE [Created pursuant to sec. 5(a) of Public Law 304, 79th Congress] SENATE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES PAUL S. SARBANES, Maryland, LEE H. HAMILTON, Indiana, Chairman Vice Chairman WILLIAM PROXMIRE, Wisconsin AUGUSTUS F. HAWKINS, California LLOYD BENTSEN, Texas DAVID R. OBEY, Wisconsin EDWARD M. KENNEDY, Massachusetts JAMES H. SCHEUER, New York JOHN MELCHER, Montana FORTNEY H. (PETE) STARK, California JEFF BINGAMAN, New Mexico STEPHEN J. SOLARZ, New York WILLIAM V. ROTH, JR., Delaware CHALMERS P. WYLIE, Ohio STEVE SYMMS, Idaho OLYMPIA J. SNOWE, Maine ALFONSE M. D'AMATO, New York HAMILTON FISH, JR., New York PETE WILSON, California J. ALEX McMILLAN, North Carolina JUDITH DAVISON, Executive Director RICHARD F KAUFMAN, General Counsel STEPHEN QUICK, Chief Economist ROBERT J. TOSTERUD, Minority Assistant Director SUBCOMMITTEE ON ECONOM IC RESOURCES AND COMPETITIVENESS HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES SENATE DAVID R. OBEY, Wisconsin, Chairman JOHN MELCHER, Montana JAMES H. SCHEUER, New York JEFF BINGAMAN, New Mexico CHALMERS P. WYLIE, Ohio STEVE SYMMS, Idaho J. ALEX McMILLAN, North Carolina (11) CONTENTS WITNESSES AND STATEMENTS FRIDAY, JUNE 12, 1987 Page Bingaman, Hon. Jeff, member of the Subcommittee on Economic Resources and Competitiveness, presiding: Opening statement .....................