The L. & H. Huning Mercantile Company

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Crime, Law Enforcement, and Punishment

Shirley Papers 48 Research Materials, Crime Series Inventory Box Folder Folder Title Research Materials Crime, Law Enforcement, and Punishment Capital Punishment 152 1 Newspaper clippings, 1951-1988 2 Newspaper clippings, 1891-1938 3 Newspaper clippings, 1990-1993 4 Newspaper clippings, 1994 5 Newspaper clippings, 1995 6 Newspaper clippings, 1996 7 Newspaper clippings, 1997 153 1 Newspaper clippings, 1998 2 Newspaper clippings, 1999 3 Newspaper clippings, 2000 4 Newspaper clippings, 2001-2002 Crime Cases Arizona 154 1 Cochise County 2 Coconino County 3 Gila County 4 Graham County 5-7 Maricopa County 8 Mohave County 9 Navajo County 10 Pima County 11 Pinal County 12 Santa Cruz County 13 Yavapai County 14 Yuma County Arkansas 155 1 Arkansas County 2 Ashley County 3 Baxter County 4 Benton County 5 Boone County 6 Calhoun County 7 Carroll County 8 Clark County 9 Clay County 10 Cleveland County 11 Columbia County 12 Conway County 13 Craighead County 14 Crawford County 15 Crittendon County 16 Cross County 17 Dallas County 18 Faulkner County 19 Franklin County Shirley Papers 49 Research Materials, Crime Series Inventory Box Folder Folder Title 20 Fulton County 21 Garland County 22 Grant County 23 Greene County 24 Hot Springs County 25 Howard County 26 Independence County 27 Izard County 28 Jackson County 29 Jefferson County 30 Johnson County 31 Lafayette County 32 Lincoln County 33 Little River County 34 Logan County 35 Lonoke County 36 Madison County 37 Marion County 156 1 Miller County 2 Mississippi County 3 Monroe County 4 Montgomery County -

The New York City Draft Riots of 1863

University of Kentucky UKnowledge United States History History 1974 The Armies of the Streets: The New York City Draft Riots of 1863 Adrian Cook Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Cook, Adrian, "The Armies of the Streets: The New York City Draft Riots of 1863" (1974). United States History. 56. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_united_states_history/56 THE ARMIES OF THE STREETS This page intentionally left blank THE ARMIES OF THE STREETS TheNew York City Draft Riots of 1863 ADRIAN COOK THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY ISBN: 978-0-8131-5182-3 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 73-80463 Copyright© 1974 by The University Press of Kentucky A statewide cooperative scholarly publishing agency serving Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky State College, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. Editorial and Sales Offices: Lexington, Kentucky 40506 To My Mother This page intentionally left blank Contents Acknowledgments ix -

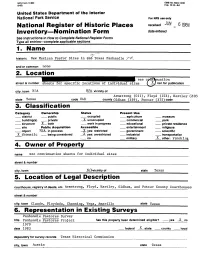

61934 Inventory Nomination Form Date Entered 1. Name 5. Location Of

NPS Form 10-900 0MB No. 1024-0018 (3-82) Exp. 10-31-84 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service For NPS use only National Register of Historic Places received JUN _ 61934 Inventory Nomination Form date entered See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type ail entries complete applicable sections _______________________________ 1. Name historic New Mexican Pastor Sites in this Texas Panhandle and/or common none 2. Location see c»nE*nuation street & number sheets for specific locations of individual sites ( XJ not for publication city, town vicinity of Armstrong (Oil), Floyd (153), Hartley (205 state Texas code 048 county Qldham (359), Potter (375) code______ Category Ownership Status Present Use district public occupied agriculture museum building(s) private X unoccupied commercial park structure X both work in progress educational private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious object N/A jn process X yes: restricted government scientific X thematic being considered X yes: unrestricted industrial transportation no military X other- ranrh-f-ng 4. Owner of Property name see continuation sheets for individual sites street & number city, town JI/Avicinity of state Texas 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Armstrong, Floyd, Hartley, Oldham, and Potter County Courthouses street & number city, town Claude, Floydada, Channing, Vega, Amarillo state Texas 6. Representation in Existing Surveys Panhandle Pastores Survey title Panhandle Pastores -

American Indian Child Removal in Arizona in the Era of Assimilation

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications, Department of History History, Department of March 2004 A Battle for the Children: American Indian Child Removal in Arizona in the Era of Assimilation Margaret D. Jacobs University of Nebraska - Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/historyfacpub Part of the History Commons Jacobs, Margaret D., "A Battle for the Children: American Indian Child Removal in Arizona in the Era of Assimilation" (2004). Faculty Publications, Department of History. 3. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/historyfacpub/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications, Department of History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. A BATTLE FOR THE CHILDREN American Indian Child Removal in Arizona in the Era of Assimilation by Margaret D. Jacobs n 1906, Helen Sekaquaptewa “awoke to fi nd [her] camp sur- Irounded by troops.” She later recalled that a government offi cial “called the men together, ordering the women and children to remain in their separate family groups. He told the men . that the govern- ment had reached the limit of its patience; that the children would have to go to school.” Helen went on to relate how “All children of school age were lined up to be registered and taken away to school. Eighty-two children, including [Helen], were taken to the school- house ... with military escort.” Helen Sekaquaptewa, a Hopi girl from Oraibi, was just one of many American Indian children who, from the 1880s up to the 1930s, were forced by U.S. -

Desired Future Conditions for Southwestern Riparian Ecosystems

Human impacts on riparian ecosystems of the Middle Rio Grande Valley during historic times Frank E. Wozniak’ Abstract.-The development of irrigation agriculture in historic times has profoundly impacted riparian ecosystems in the Middle Rio Grande Valley of New Mexico. A vital relationship has existed between water resources and settlement in the semi-arid Southwest since prehistoric times. Levels of technology have influenced human generated changes in the riparian ecosys- tems of the Middle Rio Grande Valley. The relationship of humans with the riparian levels of technology have been broadly defined but ecosystems of the Middle Rio Grande Valley has specifics have yet to be developed by researchers. been and is complex. The foundations for an These elements should include the introduction of understanding of historic human land uses are to intensive irrigation agriculture by the Spanish in be found in environmental, cultural, political and the 17th century and building of railroads by the socio-economic factors and processes. The relation- Anglo-Americans in the 19th century as well as the ship of humans with the land is based on and impacts of the introductions of plants and animals regulated by resource availability, environmental by the Euro-Americans throughout the last 450 conditions, levels of technological knowledge, years. political and socio-economic structures and cul- In this paper, we will look at the development of tural values regarding land and water and their irrigation agriculture and its impacts on riparian uses. ecosystems in the Middle Rio Grande Valley of During historic times, the riparian resources of New Mexico during historic times (e.g. -

Hidalgo County Historical Museum Archives

Museum of South Texas History Archives Photo Collection Subject Index Inventory Headings List Revision: January 2016 Consult archivist for finding aids relating to photo collections, negatives, slides, stereographs, or exhibit images. HEADING KEY I. Places II. People III. Activity IV. Things The HEADING lists are normally referred to only by their Roman numeral. For example, II includes groups and organizations, and III includes events and occupations. Each of the four HEADING lists is in upper case arranged alphabetically. Occasionally, subheadings appear as italics or with underlining, such as I GOVT BUILDINGS Federal Linn Post Office. Infrequently sub- subheading may appear, indicated by another right margin shift. Beneath each HEADING, Subheading, or Sub-subheading are folder titles. KEY HEADINGS = All Caps Subheadings= Underlined Folder Title = Regular Capitalization A I. AERIAL Brownsville/Matamoros Edinburg/Pan American/HCHM Elsa/Edcouch Hidalgo La Blanca Linn McAllen Madero McAllen Mission/Sharyland Mexico Padre Island, South/Port Isabel Pharr Rio Grande City/Fort Ringgold San Antonio Weslaco I. AGRICULTURE/SUPPLIES/BUSINESSES/AGENCIES/SEED and FEED I. AIRBASES/AIRFIELDS/AIRPORTS Brownsville Harlingen McAllen (Miller) Mercedes Moore World War II Korea Screwworm/Agriculture/Medical Science Projects Reynosa San Benito I. ARCHEOLOGY SITES Boca Chica Shipwreck Mexico I. AUCTION HOUSES B I. BACKYARDS I. BAKERIES/ PANADERIAS I. BANDSTANDS/QIOSCOS/KIOSKS/PAVILIONS Edinburg Mexico Rio Grande City 2 I. BANKS/SAVINGS AND LOANS/CREDIT UNIONS/INSURANCE AGENCIES/ LOAN COMPANY Brownsville Edinburg Chapin Edinburg State First National First State (NBC) Groundbreaking Construction/Expansion Completion Openings Exterior Interior Elsa Harlingen Hidalgo City La Feria McAllen First National Bank First State McAllen State Texas Commerce Mercedes Mission Monterrey San Antonio San Benito San Juan I. -

Ranch Women of the Old West

Hereford Women Ranch Women of the Old West by Sandra Ostgaard Women certainly made very return to one’s hometown to find and the Jesse Evans Gang, Tunstall important contributions to a bride — or if the individual had hired individuals, including Billy America’s Western frontier. There a wife, to make arrangement to the Kid, Chavez y Chavez, Dick are some interesting stories about take her out West. This was the Brewer, Charlie Bowdre and the introduction of women in the beginning of adventure for many Doc Scurlock. The two factions West — particularly as cattlewomen a frontier woman. clashed over Tunstall’s death, with and wives of ranchers. These numerous people being killed women were not typical cowgirls. Susan McSween by both sides and culminating The frontier woman worked Susan McSween in the Battle of Lincoln, where hard in difficult settings and (Dec. 30, 1845- Susan was present. Her husband contributed in a big way to Jan. 3, 1931) was killed at the end of the civilizing the West. For the most was a prominent battle, despite being unarmed part, women married to ranchers cattlewoman of and attempting to surrender. were brought to the frontier after the 19th century. Susan struggled in the the male established himself. Once called the aftermath of the Lincoln County Conditions were rough in the “Cattle Queen of New Mexico,” War to make ends meet in the decade after the Civil War, making the widow of Alexander McSween, New Mexico Territory. She sought it difficult for men to provide who was a leading factor in the and received help from Tunstall’s suitable living conditions for Lincoln County War and was shot family in England. -

Eddy County Petroleum Industry Impact on New Mexico, 2012-2018

Eddy County Petroleum Industry Impact on New Mexico, 2012-2018 December 2019 Prepared by Dr. Kramer Winingham Arrowhead Center Brooke Montgomery Arrowhead Center Trashard Mays Arrowhead Center Chris Dunn Dunn Consulting Arrowhead Center New Mexico State University Las Cruces, NM 88003 arrowheadcenter.nmsu.edu Eddy County Petroleum Industry Impact on New Mexico, 2012-2018 December 2019 Prepared by Dr. Kramer Winingham Arrowhead Center Brooke Montgomery Arrowhead Center Trashard Mays Arrowhead Center Chris Dunn Dunn Consulting Arrowhead Center New Mexico State University Las Cruces, NM 88003 Please send comments or questions to [email protected] This page is left blank intentionally Executive Summary Eddy County New Mexico has contracted Arrowhead Center at New Mexico State University to prepare a study of the impacts of Eddy County’s petroleum industry1 on New Mexico from 2012-2018. Eddy County is currently experiencing a tremendous oil boom. New technology advances and discoveries have made land in this area part of the most attractive oil play in the world. For the first time since 1973, the United States has become the top oil producing nation in the world, driven by oil production in the Permian Basin.2 Recent assessments of oil and gas reserves in the Delaware Basin3 near Carlsbad, New Mexico have reported the largest continuous oil and gas resources ever discovered.4 These new discoveries and subsequent drilling have produced many benefits - increased employment, economic output, and government revenue. The purpose of this impact study is to attempt to quantify and estimate the impact of Eddy County’s petroleum industry on New Mexico from 2012-2018. -

Red and White on the Silver Screen: the Shifting Meaning and Use of American Indians in Hollywood Films from the 1930S to the 1970S

RED AND WHITE ON THE SILVER SCREEN: THE SHIFTING MEANING AND USE OF AMERICAN INDIANS IN HOLLYWOOD FILMS FROM THE 1930s TO THE 1970s a dissertation submitted to Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Bryan W. Kvet May, 2016 (c) Copyright All rights reserved Except for previously published materials Dissertation Written by Bryan W. Kvet B.A., Grove City College, 1994 M.A., Kent State University, 1998 Ph.D., Kent State University, 2015 Approved by ___Kenneth Bindas_______________, Chair, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Dr. Kenneth Bindas ___Clarence Wunderlin ___________, Members, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Dr. Clarence Wunderlin ___James Seelye_________________, Dr. James Seelye ___Bob Batchelor________________, Dr. Bob Batchelor ___Paul Haridakis________________, Dr. Paul Haridakis Accepted by ___Kenneth Bindas_______________, Chair, Department of History Dr. Kenneth Bindas ___James L. Blank________________, Dean, College of Arts and Sciences Dr. James L. Blank TABLE OF CONTENTS…………………………………………………………………iv LIST OF FIGURES………………………………………………………………………v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS……………………………………………………………...vii CHAPTERS Introduction………………………………………………………………………1 Part I: 1930 - 1945 1. "You Haven't Seen Any Indians Yet:" Hollywood's Bloodthirsty Savages……………………………………….26 2. "Don't You Realize this Is a New Empire?" Hollywood's Noble Savages……………………………………………...72 Epilogue for Part I………………………………………………………………..121 Part II: 1945 - 1960 3. "Small Warrior Should Have Father:" The Cold War Family in American Indian Films………………………...136 4. "In a Hundred Years it Might've Worked:" American Indian Films and Civil Rights………………………………....185 Epilogue for Part II……………………………………………………………….244 Part III, 1960 - 1970 5. "If Things Keep Trying to Live, the White Man Will Rub Them Out:" The American Indian Film and the Counterculture………………………260 6. -

Renewing the Creative Economy of New Mexico

Building on the Past, Facing the Future: Renewing the Creative Economy of New Mexico Jeffrey Mitchell And Gillian Joyce With Steven Hill And Ashley M. Hooper 2014 This report was commissioned by the New Mexico Department of Cultural Affairs and prepared by UNM’s Bureau of Business and Economic Research. As will be discussed in this report, we interviewed arts and culture workers and entrepreneurs across the state of New Mexico. We asked them for two words to describe New Mexico in general and for two words to describe how New Mexico has changed. We entered these data into a ’word cloud’ software program. The program visually represents the data so that the more often a word is mentioned, the larger it appears. The figure above is a representation of the words offered by members of the New Mexico creative economy when interviewed for this project. Acknowledgements We would like to thank Secretary Veronica Gonzales for her vision – without her, this project would not have been possible. Also, at the Department of Cultural Affairs we would like to thank Anne Green-Romig, Loie Fecteau and Paulius Narbutas for their support and patience. At the Department of Tourism, we would like to thank Jim Orr for his help with tourism data. We owe a debt of gratitude to the more than 200 arts and culture workers throughout the state who took time out of their days to offer their insights and experiences in the arts and culture industries of New Mexico. At UNM-BBER, we would like to thank Jessica Hitch for her intrepid data collection, Catherine A. -

Preservation Ethics in the Case of Nebraska's Nationally Registered Historic Properties

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Theses and Dissertations in Geography Geography Program (SNR) Summer 7-29-2010 PRESERVATION ETHICS IN THE CASE OF NEBRASKA’S NATIONALLY REGISTERED HISTORIC PROPERTIES Darren Michael Adams University of Nebraska at Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/geographythesis Part of the Agency Commons, American Politics Commons, American Popular Culture Commons, Architectural History and Criticism Commons, Bilingual, Multilingual, and Multicultural Education Commons, Community-Based Research Commons, Construction Law Commons, Cultural History Commons, Cultural Resource Management and Policy Analysis Commons, Economic History Commons, Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons, History of Religion Commons, Human Geography Commons, Indian and Aboriginal Law Commons, Legislation Commons, Other Legal Studies Commons, Other Political Science Commons, Other Public Affairs, Public Policy and Public Administration Commons, Place and Environment Commons, Political Economy Commons, Political History Commons, Politics and Social Change Commons, Public Administration Commons, Race and Ethnicity Commons, Regional Sociology Commons, Religion Law Commons, Rural Sociology Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, Social History Commons, Social Policy Commons, Sociology of Culture Commons, Tourism Commons, Urban, Community and Regional Planning Commons, Urban Studies Commons, and the Urban Studies and Planning Commons Adams, Darren Michael, "PRESERVATION ETHICS IN THE CASE OF NEBRASKA’S NATIONALLY REGISTERED HISTORIC PROPERTIES" (2010). Theses and Dissertations in Geography. 6. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/geographythesis/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Geography Program (SNR) at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations in Geography by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. -

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 065 384 SO 002 574 TITLE Outline of Content: Mexican American Studies. Grades INSTITUTION Los Angeles City Sc

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 065 384 SO 002 574 TITLE Outline of Content: Mexican American Studies. Grades 10-12. INSTITUTION Los Angeles City Schools, Calif. Div. of Instructional Planning and Services. PUB DATE 68 NOTE 57p. EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$3.29 DESCRIPTORS American History; *Cultural Awareness; Cultural Background; Curriculum Guides; Ethnic Groups; Ethnic Studies; *Mexican American History; *Mexican Americans; Minority Groups; Secondary Grades; *Social Studies Units; Spanish Americans; *United States History ABSTRACT An historical survey of Mexican Americans of the Southwest is outlined in this curriculum guide for high school students. The purpose of this course is to have students develop an appreciation for and an understanding of the role of the Mexican American in the development of the United States. Although the first half of the guide focuses upon the historical cultural background of Mexican Americans, the latter half emphases the culture conflict within the ethnic group and, moreover, their strnggle toward obtaining civil rights along with improvement of social and economic conditions. Five units are: 1) Spain in the New World; 2) The Collision of Two Cultures; 3) The Mexican American Heritage in the American Southwest; 4) A Sociological and Psychological View of the Mexican American; and 5) The Mexican American today. An appendix includes Mexican American winners of the Congressional Medal of Honor. Also included is a book and periodical bibliography. (SJM) -411 ' U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, EDUCATION S WELFARE OFFICE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRO- DUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIG- INATING IT. POINTS OF VIEW OR OPIN- IONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICE OF EDU- CATION POSITION OR POLICY.