Farmers, Hunters, and Colonists: Interaction Between the Southwest and the Southern Plains

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A History of Fort Bascom in the Canadian River Valley

New Mexico Historical Review Volume 87 Number 3 Article 4 7-1-2012 Boots on the Ground: A History of Fort Bascom in the Canadian River Valley James Blackshear Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr Recommended Citation Blackshear, James. "Boots on the Ground: A History of Fort Bascom in the Canadian River Valley." New Mexico Historical Review 87, 3 (2012). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr/vol87/iss3/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in New Mexico Historical Review by an authorized editor of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. Boots on the Ground a history of fort bascom in the canadian river valley James Blackshear n 1863 the Union Army in New Mexico Territory, prompted by fears of a Isecond Rebel invasion from Texas and its desire to check incursions by southern Plains Indians, built Fort Bascom on the south bank of the Canadian River. The U.S. Army placed the fort about eleven miles north of present-day Tucumcari, New Mexico, a day’s ride from the western edge of the Llano Estacado (see map 1). Fort Bascom operated as a permanent post from 1863 to 1870. From late 1870 through most of 1874, it functioned as an extension of Fort Union, and served as a base of operations for patrols in New Mexico and expeditions into Texas. Fort Bascom has garnered little scholarly interest despite its historical signifi cance. -

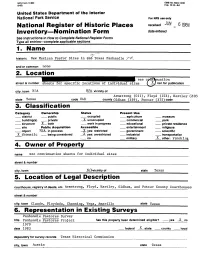

61934 Inventory Nomination Form Date Entered 1. Name 5. Location Of

NPS Form 10-900 0MB No. 1024-0018 (3-82) Exp. 10-31-84 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service For NPS use only National Register of Historic Places received JUN _ 61934 Inventory Nomination Form date entered See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type ail entries complete applicable sections _______________________________ 1. Name historic New Mexican Pastor Sites in this Texas Panhandle and/or common none 2. Location see c»nE*nuation street & number sheets for specific locations of individual sites ( XJ not for publication city, town vicinity of Armstrong (Oil), Floyd (153), Hartley (205 state Texas code 048 county Qldham (359), Potter (375) code______ Category Ownership Status Present Use district public occupied agriculture museum building(s) private X unoccupied commercial park structure X both work in progress educational private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious object N/A jn process X yes: restricted government scientific X thematic being considered X yes: unrestricted industrial transportation no military X other- ranrh-f-ng 4. Owner of Property name see continuation sheets for individual sites street & number city, town JI/Avicinity of state Texas 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Armstrong, Floyd, Hartley, Oldham, and Potter County Courthouses street & number city, town Claude, Floydada, Channing, Vega, Amarillo state Texas 6. Representation in Existing Surveys Panhandle Pastores Survey title Panhandle Pastores -

CHAMPION AEROSPACE LLC AVIATION CATALOG AV-14 Spark

® CHAMPION AEROSPACE LLC AVIATION CATALOG AV-14 REVISED AUGUST 2014 Spark Plugs Oil Filters Slick by Champion Exciters Leads Igniters ® Table of Contents SECTION PAGE Spark Plugs ........................................................................................................................................... 1 Product Features ....................................................................................................................................... 1 Spark Plug Type Designation System ............................................................................................................. 2 Spark Plug Types and Specifications ............................................................................................................. 3 Spark Plug by Popular Aircraft and Engines ................................................................................................ 4-12 Spark Plug Application by Engine Manufacturer .........................................................................................13-16 Other U. S. Aircraft and Piston Engines ....................................................................................................17-18 U. S. Helicopter and Piston Engines ........................................................................................................18-19 International Aircraft Using U. S. Piston Engines ........................................................................................ 19-22 Slick by Champion ............................................................................................................................. -

José Piedad Tafoya, 1834–1913

New Mexico Historical Review Volume 81 Number 1 Article 3 1-1-2006 Comanchero: José Piedad Tafoya, 1834–1913 Thomas Merlan Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr Recommended Citation Merlan, Thomas. "Comanchero: José Piedad Tafoya, 1834–1913." New Mexico Historical Review 81, 1 (). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr/vol81/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in New Mexico Historical Review by an authorized editor of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. Comanchero JOSE PIEDAD TAFOYA, 1834-1913 Thomas Merlan and Frances Levine ose Piedad Tafoya is generally known as a comanchero who traded with Jthe Native people of the Southern Plains during the mid- to late nine teenth century. Born in a New Mexican village on the then far northern frontier of Mexico, he died in a village scarcely twenty-five miles away in the new U.S. state ofNew Mexico. The label comanchero, however, was an inadequate description of Tafoya, for he was also an army scout, farmer, rancher, man of property, and family man. Later, like a number of his New Mexican contemporaries who observed the changing character of territo rial New Mexico, he sent his son to be educated at St. Michael's College in Santa Fe. The purpose here is not only to review an<;l supplement the facts ofTafoya's life as a comanchero but to offer a biographical essay on a man whose life spanned two major economic and cultural networks. -

Vaya Con Dios, Kemosabe: the Multilingual Space of Westerns from 1945 to 1976

https://doi.org/10.5007/2175-7968.2020v40n2p282 VAYA CON DIOS, KEMOSABE: THE MULTILINGUAL SPACE OF WESTERNS FROM 1945 TO 1976 William F. Hanes1 1Pesquisador Autônomo, Niterói, Rio de Janeiro, Brasil Abstract: Since the mythic space of the Western helped shape how Americans view themselves, as well as how the world has viewed them, the characterization of Native American, Hispanic, and Anglo interaction warrants closer scrutiny. For a corpus with substantial diachrony, every Western in the National Registry of Films produced between the end of the Second World War and the American Bicentennial (1945-1976), i.e. the cultural apex of the genre, was assessed for the presence of foreign language and interpretation, the relationship between English and social power, and change over time. The analysis showed that although English was universally the language of power, and that the social status of characters could be measured by their fluency, there was a significant presence of foreign language, principally Spanish (63% of the films), with some form of interpretation occurring in half the films. Questions of cultural identity were associated with multilingualism and, although no diachronic pattern could be found in the distribution of foreign language, protagonism for Hispanics and Native Americans did grow over time. A spectrum of narrative/cinematic approaches to foreign language was determined that could be useful for further research on the presentation of foreigners and their language in the dramatic arts. Keywords: Westerns, Hollywood, Multilingualism, Cold War, Revisionism VAYA CON DIOS, KEMOSABE: O ESPAÇO MULTILINGUE DE FAROESTES AMERICANOS DE 1945 A 1976 Resumo: Considerando-se que o espaço mítico do Faroeste ajudou a dar forma ao modo como os norte-americanos veem a si mesmos, e também Esta obra utiliza uma licença Creative Commons CC BY: https://creativecommons.org/lice William F. -

Desired Future Conditions for Southwestern Riparian Ecosystems

Human impacts on riparian ecosystems of the Middle Rio Grande Valley during historic times Frank E. Wozniak’ Abstract.-The development of irrigation agriculture in historic times has profoundly impacted riparian ecosystems in the Middle Rio Grande Valley of New Mexico. A vital relationship has existed between water resources and settlement in the semi-arid Southwest since prehistoric times. Levels of technology have influenced human generated changes in the riparian ecosys- tems of the Middle Rio Grande Valley. The relationship of humans with the riparian levels of technology have been broadly defined but ecosystems of the Middle Rio Grande Valley has specifics have yet to be developed by researchers. been and is complex. The foundations for an These elements should include the introduction of understanding of historic human land uses are to intensive irrigation agriculture by the Spanish in be found in environmental, cultural, political and the 17th century and building of railroads by the socio-economic factors and processes. The relation- Anglo-Americans in the 19th century as well as the ship of humans with the land is based on and impacts of the introductions of plants and animals regulated by resource availability, environmental by the Euro-Americans throughout the last 450 conditions, levels of technological knowledge, years. political and socio-economic structures and cul- In this paper, we will look at the development of tural values regarding land and water and their irrigation agriculture and its impacts on riparian uses. ecosystems in the Middle Rio Grande Valley of During historic times, the riparian resources of New Mexico during historic times (e.g. -

June 2015 Th SSAASSSS CCOONNVVEENNTTIIOONN San Antonio , 12 by Capitan in George Baylor, SASS Life #24287 Regulator Photos by Black Jack Mcginnis, SASS #2041

!! S S C For Updates, Information and GREAT Offers on the fly-Text SASS to 772937! A ig L CCCooowwwCCbbboooywywy CbbCCoohhyhyrr r oCoConnnhhiiiiirccrcclollolleeeneniiccllee I November 2001 CowCboyw Cbohyr oCSnhircloe niicnlle PaCge 1 NNSNSoeeoopvpvvetteteememmmmbbbbbeeeererrr r 2 2 2 2020000001111 00 S - PPPPaaaagggKgeeee 1 111 E u H ( p E S N R e D T E Cowboy Chroniiclle e o ! October 2010 P page 1o d ! October 2010 a a g f y ~ e T R ! 7 A The Cowboy Chronicle ) I L The Monthly Journal of the Single Action Sh ooting Society ® Vol. 28 No. 6 © Single Action Shooting Society, Inc. June 2015 th SSAASSSS CCOONNVVEENNTTIIOONN San Antonio , 12 By CapItan in George Baylor, SASS Life #24287 Regulator Photos by Black Jack McGinnis, SASS #2041 he Menger Hotel, San Antonio, TTexas, January 7-11, 2015. The Alamo is next door. The Alamo—only a small portion survives. It is a place of legend. The siege of the Alamo defines Texas. In 1836 for 13 days a few Texians held an indefensible mission from the most powerful army on the continent, Santa Anna’s Mexican army. The Texi - ans were outnumbered by more than ten to one. The Alamo fell on the morn - ing of March 6, 1836, and the defenders died to the last man. Sam Houston would rouse his troops with “Remember Historical impersonator Tom Jackson (complete with U.S. Krag carbine) the Alamo,” and “Remember Goliad.” On at the Menger Bar recreates what it would have been like to be a bright, sunshiny April afternoon, recruited into the Rough Riders by Theodore Roosevelt. -

Eddy County Petroleum Industry Impact on New Mexico, 2012-2018

Eddy County Petroleum Industry Impact on New Mexico, 2012-2018 December 2019 Prepared by Dr. Kramer Winingham Arrowhead Center Brooke Montgomery Arrowhead Center Trashard Mays Arrowhead Center Chris Dunn Dunn Consulting Arrowhead Center New Mexico State University Las Cruces, NM 88003 arrowheadcenter.nmsu.edu Eddy County Petroleum Industry Impact on New Mexico, 2012-2018 December 2019 Prepared by Dr. Kramer Winingham Arrowhead Center Brooke Montgomery Arrowhead Center Trashard Mays Arrowhead Center Chris Dunn Dunn Consulting Arrowhead Center New Mexico State University Las Cruces, NM 88003 Please send comments or questions to [email protected] This page is left blank intentionally Executive Summary Eddy County New Mexico has contracted Arrowhead Center at New Mexico State University to prepare a study of the impacts of Eddy County’s petroleum industry1 on New Mexico from 2012-2018. Eddy County is currently experiencing a tremendous oil boom. New technology advances and discoveries have made land in this area part of the most attractive oil play in the world. For the first time since 1973, the United States has become the top oil producing nation in the world, driven by oil production in the Permian Basin.2 Recent assessments of oil and gas reserves in the Delaware Basin3 near Carlsbad, New Mexico have reported the largest continuous oil and gas resources ever discovered.4 These new discoveries and subsequent drilling have produced many benefits - increased employment, economic output, and government revenue. The purpose of this impact study is to attempt to quantify and estimate the impact of Eddy County’s petroleum industry on New Mexico from 2012-2018. -

Renewing the Creative Economy of New Mexico

Building on the Past, Facing the Future: Renewing the Creative Economy of New Mexico Jeffrey Mitchell And Gillian Joyce With Steven Hill And Ashley M. Hooper 2014 This report was commissioned by the New Mexico Department of Cultural Affairs and prepared by UNM’s Bureau of Business and Economic Research. As will be discussed in this report, we interviewed arts and culture workers and entrepreneurs across the state of New Mexico. We asked them for two words to describe New Mexico in general and for two words to describe how New Mexico has changed. We entered these data into a ’word cloud’ software program. The program visually represents the data so that the more often a word is mentioned, the larger it appears. The figure above is a representation of the words offered by members of the New Mexico creative economy when interviewed for this project. Acknowledgements We would like to thank Secretary Veronica Gonzales for her vision – without her, this project would not have been possible. Also, at the Department of Cultural Affairs we would like to thank Anne Green-Romig, Loie Fecteau and Paulius Narbutas for their support and patience. At the Department of Tourism, we would like to thank Jim Orr for his help with tourism data. We owe a debt of gratitude to the more than 200 arts and culture workers throughout the state who took time out of their days to offer their insights and experiences in the arts and culture industries of New Mexico. At UNM-BBER, we would like to thank Jessica Hitch for her intrepid data collection, Catherine A. -

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 065 384 SO 002 574 TITLE Outline of Content: Mexican American Studies. Grades INSTITUTION Los Angeles City Sc

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 065 384 SO 002 574 TITLE Outline of Content: Mexican American Studies. Grades 10-12. INSTITUTION Los Angeles City Schools, Calif. Div. of Instructional Planning and Services. PUB DATE 68 NOTE 57p. EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$3.29 DESCRIPTORS American History; *Cultural Awareness; Cultural Background; Curriculum Guides; Ethnic Groups; Ethnic Studies; *Mexican American History; *Mexican Americans; Minority Groups; Secondary Grades; *Social Studies Units; Spanish Americans; *United States History ABSTRACT An historical survey of Mexican Americans of the Southwest is outlined in this curriculum guide for high school students. The purpose of this course is to have students develop an appreciation for and an understanding of the role of the Mexican American in the development of the United States. Although the first half of the guide focuses upon the historical cultural background of Mexican Americans, the latter half emphases the culture conflict within the ethnic group and, moreover, their strnggle toward obtaining civil rights along with improvement of social and economic conditions. Five units are: 1) Spain in the New World; 2) The Collision of Two Cultures; 3) The Mexican American Heritage in the American Southwest; 4) A Sociological and Psychological View of the Mexican American; and 5) The Mexican American today. An appendix includes Mexican American winners of the Congressional Medal of Honor. Also included is a book and periodical bibliography. (SJM) -411 ' U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, EDUCATION S WELFARE OFFICE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRO- DUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIG- INATING IT. POINTS OF VIEW OR OPIN- IONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICE OF EDU- CATION POSITION OR POLICY. -

Cultural Resource Survey for the Lower Cow Creek Restoration Project, San Miguel County, New Mexico

CULTURAL RESOURCE SURVEY FOR THE LOWER COW CREEK RESTORATION PROJECT, SAN MIGUEL COUNTY, NEW MEXICO PREPARED FOR Pathfinder Environmental, LLC PREPARED BY Okun Consulting Solutions AUGUST 2018 Okun Consulting Solutions NMCRIS ACTIVITY NUMBER 141269 CULTURAL RESOURCE SURVEY FOR THE LOWER COW CREEK RESTORATION PROJECT, SAN MIGUEL COUNTY, NEW MEXICO Prepared for Pathfinder Environmental, LLC 1800 Old Pecos Trail, Suite E Santa Fe, NM 87505 Prepared and Submitted by Adam Okun, Principal Investigator Okun Consulting Solutions 441 Morningside Dr. NE Albuquerque, NM 87108 Reviewing Agencies United States Army Corps of Engineers New Mexico Historic Preservation Division Survey Conducted Under New Mexico General Archaeological Investigation Permit Number: NM-18-285-S Okun Consulting Report Number: OCS-2018-24 Okun Consulting Solutions LOWER COW CREEK RESTORATION PROJECT ABSTRACT The Upper Pecos Watershed Association is proposing a riparian restoration project along lower Cow Creek in San Miguel County, New Mexico. The project is approximately 0.75 miles long and is located less than 1 mile northwest of the town of North San Ysidro. Cow Creek is designated as a cold-water fishery, but water quality in the creek is currently impaired by high temperatures. The purpose of the proposed project is to reduce the water temperature in the creek, which is needed to support its designated use and improve riparian habitat. The project is being funded by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) through the Surface Water Bureau of the New Mexico Environment Department. It will take place entirely on private lands. A variety of restoration treatments are proposed, which will alleviate stream entrenchment and riverbank erosion and improve riparian habitat. -

Ecology, Diversity, and Sustainability of the Middle Rio Grande Basin

This file was created by scanning the printed publication. Errors identified by the software have been corrected; however, some errors may remain. Chapter 3 Human Ecology and Ethnology Frank E. Wozniak, USDA Forest Service, Southwestern Regional Office, Albuquerque, New Mexico ies similar to that of de Buys (1985) on the Sangre de HISTORIC PERIODS Cristos would contribute significantly to our under Spanish Colonial A.D. 1540-1821 standing of the human role, human impacts, and Mexican A.D. 1821-1846 human relationships with the land, water, and other Territorial A.D. 1846-1912 resources of the Middle Rio Grande Basin during Statehood A.D. 1912-present historic times. Farming, ranching, hunting, mining, logging, and other human activities have signifi cantly affected Basin ecosystems in the last 450 years. Most of the research on resource availability and INTRODUCTION its role in regulating human impacts on the Basin has The relationship of humans with Middle Rio focused on the 20th century. Some work has been Grande Basin ecosystems is complex. In historic done on the second half of the 19th century but very times, humans had a critical role in the evolution of little on the 300 years of the historic era preceding environmental landscapes and ecosystems through the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848. This chap out the Middle Rio Grande Basin. The relationship ter summarizes the available historic information. of humans with the land is based on and regulated by resource availability, environmental conditions, OVERVIEW OF HUMAN IMPACTS levels of technological knowledge, political and so cioeconomic structures, and cultural values regard The principal factor influencing the human rela ing the use of land and water.