January 2003 PUBLISHER

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Review of Public Two-Year Institutions of Higher Education in New Mexico

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 103 033 JC 750 175 AUTHOR Esquibel, Antonio . TITLE A Review of Public Tvo-Year Institutions of Higher Education in New Mexico. INSTITUTION New Mexico Univ., Albuquerque. Dept. of Educational Administration. PUB DATE Dec 74 NOTE 75p. IDES PRICE MP-$0.76 HC -53.32 PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS Colleges; *Educational History; *Educational Legislation; Educational Planning; Enrollment Trends; *Junior Colleges; Literature Reviews; Post Secondary Education; *Public Education; *State of the Art Reviews IDENTIFIERS Branch Campuses; *New Mexico ABSTRACT This study vas conducted to establish *The State of the Art* of public two-year colleges in New Mexico* Previous studies of two-year institutions in New Mexico are reviewed. A historical review of two-year colleges and a legislative history of junior colleges in New Mexico are presented. Althougb Nee Mexico does not have a coordinated state system of junior colleges, enrollment in two-year institutions has increased over 200 percent during the last 10 years. New Mexico now has nine branch community college campuses, which are governed by a parent four-year college, and onlyone junior college, which is,controlled by a junior college board elected by the junior college district's voters. New Mexico also hes one military institute, three technical/vocational institutes, and five private and six public four-year institutions. In general, twoo.year colleges in New Mexico have been relegated to the status of stepchild of other institutions* Because they add prestige to the communities in which they are located, branch colleges give the parent institutions additional political clout in the state legislature; this political reality must be considered in future attempts to establish junior college legislation. -

New Mexico New Mexico

NEW MEXICO NEWand MEXICO the PIMERIA ALTA THE COLONIAL PERIOD IN THE AMERICAN SOUTHWEst edited by John G. Douglass and William M. Graves NEW MEXICO AND THE PIMERÍA ALTA NEWand MEXICO thePI MERÍA ALTA THE COLONIAL PERIOD IN THE AMERICAN SOUTHWEst edited by John G. Douglass and William M. Graves UNIVERSITY PRESS OF COLORADO Boulder © 2017 by University Press of Colorado Published by University Press of Colorado 5589 Arapahoe Avenue, Suite 206C Boulder, Colorado 80303 All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America The University Press of Colorado is a proud member of Association of American University Presses. The University Press of Colorado is a cooperative publishing enterprise supported, in part, by Adams State University, Colorado State University, Fort Lewis College, Metropolitan State University of Denver, Regis University, University of Colorado, University of Northern Colorado, Utah State University, and Western State Colorado University. ∞ This paper meets the requirements of the ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper). ISBN: 978-1-60732-573-4 (cloth) ISBN: 978-1-60732-574-1 (ebook) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Douglass, John G., 1968– editor. | Graves, William M., editor. Title: New Mexico and the Pimería Alta : the colonial period in the American Southwest / edited by John G. Douglass and William M. Graves. Description: Boulder : University Press of Colorado, [2017] | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2016044391| ISBN 9781607325734 (cloth) | ISBN 9781607325741 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Spaniards—Pimería Alta (Mexico and Ariz.)—History. | Spaniards—Southwest, New—History. | Indians of North America—First contact with Europeans—Pimería Alta (Mexico and Ariz.)—History. -

Mesilla Valley Bosque State Park Doña Ana County, New Mexico

MESILLA VALLEY BOSQUE STATE PARK DOÑA ANA COUNTY, NEW MEXICO VEGETATION SURVEY Robert Sivinski EMNRD-Forestry Division August 2005 OVERVIEW The proposed Mesilla Valley Bosque State Park consists of west bank Rio Grande floodplain roughly between the Mesilla Dam and the State Road 538 Bridge. Several hundred acres of desert uplands occur to the east of the southern half of this river park. Substrates are mostly recent alluvial and colluvial deposits and generally consist of alkaline, sandy soils. Some of the lowest areas in the floodplain have alkaline silt and fine sand soils, and there are a few clayey outcrops in the desert uplands. The vegetation in this park area has been heavily impacted by river channelization, irrigation ditches, drains, roads and off-road vehicles, alien weeds (especially saltcedar), and centuries of livestock grazing. Nevertheless, there are some interesting remnants of the original Rio Grande floodplain in this area. The saltgrass/sacaton flat between the levee and irrigation ditch is especially noteworthy. Despite a few vague irrigation or drainage furrows, I believe this alkaline grassland (with a few scattered stands of cottonwood trees) is a small remnant piece of the natural vegetation community that dominated much of the middle Rio Grande floodplain prior to channelization and conversion to agriculture. This grassland is not especially diverse in species, but is the most interesting part of the park in terms of its historical significance. Plant association changes in composition and density occur frequently and gradually throughout the park and cannot be mapped with any accuracy. Therefore, the vegetation map of this survey only recognizes three major plant communities: floodplain grassland, mixed riparian (woody plants), and Chihuahuan Desert scrub (also woody plants). -

National Viticulture and Enology Extension Leadership Conference Prosser, WA 20-22 May 2018

National Viticulture and Enology Extension Leadership Conference Prosser, WA 20-22 May 2018 Hosted by: Welcome to Washington! I am very happy to host the first NVEELC in the Pacific Northwest! I hope you find the program over the next few days interesting, educational, and professionally fulfilling. We have built in multiple venues for networking, sharing ideas, and strengthening the Viticulture and Enology Extension network across North America. We would like to sincerely thank our program sponsors, as without these generous businesses and organizations, we would not be able to provide this opportunity. I would equally like to thank our travel scholarship sponsors, who are providing the assistance to help many of your colleagues attend this event. The NVEELC Planning Committee (below) has worked hard over the last year and we hope you find this event enjoyable to keep returning every year, and perhaps, consider hosting in the future! I hope you enjoy your time here in the Heart of Washington Wine Country! Cheers, Michelle M. Moyer NVEELC Planning Committee Michelle M. Moyer, Washington State University Donnell Brown, National Grape Research Alliance Keith Striegler, E. & J. Gallo Winery Hans Walter-Peterson, Cornell University Stephanie Bolton, Lodi Winegrape Commission Meeting Sponsors Sunday Opening Reception: Monday Coffee Breaks: Monday and Tuesday Lunches: Monday Dinner: Tuesday Dinner : Travel Scholarship Sponsors Map Best Western to Clore Center Westernto Clore Best PROGRAM 20-22 May 2018 _________________________________________________________________________________ Sunday, May 20 – Travel Day 6:30 pm - 8:00 pm Welcome Reception - Best Western Plus Inn at Horse Heaven - Sponsored by G.S. Long Co. _________________________________________________________________________________ Monday, May 21 – Regional Reports and Professional Development 8:00 am Depart Hotel for Walter Clore Wine and Culinary Center 8:15 am On-site registration 8:30 am Welcome and Introductions Michelle M. -

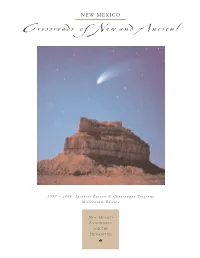

Crossroads of Newand Ancient

NEW MEXICO Crossroads of NewandAncient 1999 – 2000 Speakers Bureau & Chautauqua Programs Millennium Edition N EW M EXICO E NDOWMENT FOR THE H UMANITIES ABOUT THE COVER: AMATEUR PHOTOGRAPHER MARKO KECMAN of Aztec captures the crossroads of ancient and modern in New Mexico with this image of Comet Hale-Bopp over Fajada Butte in Chaco Culture National Historic Park. Kecman wanted to juxtapose the new comet with the butte that was an astronomical observatory in the years 900 – 1200 AD. Fajada (banded) Butte is home to the ancestral Puebloan sun shrine popularly known as “The Sun Dagger” site. The butte is closed to visitors to protect its fragile cultural sites. The clear skies over the Southwest led to discovery of Hale-Bopp on July 22-23, 1995. Alan Hale saw the comet from his driveway in Cloudcroft, New Mexico, and Thomas Bopp saw the comet from the desert near Stanfield, Arizona at about the same time. Marko Kecman: 115 N. Mesa Verde Ave., Aztec, NM, 87410, 505-334-2523 Alan Hale: Southwest Institute for Space Research, 15 E. Spur Rd., Cloudcroft, NM 88317, 505-687-2075 1999-2000 NEW MEXICO ENDOWMENT FOR THE HUMANITIES SPEAKERS BUREAU & CHAUTAUQUA PROGRAMS Welcome to the Millennium Edition of the New Mexico Endowment for the Humanities (NMEH) Resource Center Programming Guide. This 1999-2000 edition presents 52 New Mexicans who deliver fascinating programs on New Mexico, Southwest, national and international topics. Making their debuts on the state stage are 16 new “living history” Chautauqua characters, ranging from an 1840s mountain man to Martha Washington, from Governor Lew Wallace to Capitán Rafael Chacón, from Pat Garrett to Harry Houdini and Kit Carson to Mabel Dodge Luhan. -

Affidavit NM Legislature Final

To: Speaker of the House Brian Egolf State Capitol, Suite 104 490 Old Santa Fe Trail Santa Fe, NM 87501 To: President Pro Tempore Mimi Stewart 313 Moon Street NE Albuquerque, NM 87123 From: _____________________________ _____________________________ _____________________________ Notice by Affidavit to the Legislature of New Mexico State Notice of Maladministration Notice of Malfeasance Demand to End State of Public Health Emergency Notice of Change in Contract Terms Notice of Right to Arbitration Case # 2021-0704B Notice to Agent is Notice to Principal. Notice to Principal is Notice to Agent. Comes now Affiant, __________________________________________, one of the people (as seen in the New Mexico Constitution Article 2 Section 2), Sui Juris, in this Court of Record, does make the following claims: Affiant claims that the United States of America is a constitutional republic and that the Constitution guarantees to every state a republican form of government. See below: republic (n.) c. 1600, "state in which supreme power rests in the people via elected representatives," from French république (15c.) Online Etymology Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/search?q=republic&ref=searchbar_searchhint United States Constitution Article 4 Section 4 The United States shall guarantee to every state a republican form of government... Affiant claims that the New Mexico Constitution affirms that all political power is inherent in the people, and that you, as public servant and trustee, serve at the will of the people. You do not have granted authority to control the people's private affairs or to “rule over” us. Please see constitutional provisions below: New Mexico Constitution Bill of Rights Article 2 Section 2: All political power is vested in and derived from the people: all government of right originates with the people, is founded upon their will and is instituted solely for their good. -

In the Shadow of Billy the Kid: Susan Mcsween and the Lincoln County War Author(S): Kathleen P

In the Shadow of Billy the Kid: Susan McSween and the Lincoln County War Author(s): Kathleen P. Chamberlain Source: Montana: The Magazine of Western History, Vol. 55, No. 4 (Winter, 2005), pp. 36-53 Published by: Montana Historical Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4520742 . Accessed: 31/01/2014 13:20 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Montana Historical Society is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Montana: The Magazine of Western History. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 142.25.33.193 on Fri, 31 Jan 2014 13:20:15 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions In the Shadowof Billy the Kid SUSAN MCSWEEN AND THE LINCOLN COUNTY WAR by Kathleen P. Chamberlain S C.4 C-5 I t Ia;i - /.0 I _Lf Susan McSween survivedthe shootouts of the Lincoln CountyWar and createda fortunein its aftermath.Through her story,we can examinethe strugglefor economic control that gripped Gilded Age New Mexico and discoverhow women were forced to alter their behavior,make decisions, and measuresuccess againstthe cold realitiesof the period. This content downloaded from 142.25.33.193 on Fri, 31 Jan 2014 13:20:15 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions ,a- -P N1878 southeastern New Mexico declared war on itself. -

Billy the Kid and the Lincoln County War 1878

Other Forms of Conflict in the West – Billy the Kid and the Lincoln County War 1878 Lesson Objectives: Starter Questions: • To understand how the expansion of 1) We have many examples of how the the West caused other forms of expansion into the West caused conflict with tension between settlers, not just Plains Indians – can you list three examples conflict between white Americans and of conflict and what the cause was in each Plains Indians. case? • To explain the significance of the 2) Can you think of any other groups that may Lincoln County War in understanding have got into conflict with each other as other types of conflict. people expanded west and any reasons why? • To assess the significance of Billy the 3) Why was law and order such a problem in Kid and what his story tells us about new communities being established in the law and order. West? Why was it so hard to stop violence and crime? As homesteaders, hunters, miners and cattle ranchers flooded onto the Plains, they not only came into conflict with the Plains Indians who already lived there, but also with each other. This was a time of robberies, range wars and Indian wars in the wide open spaces of the West. Gradually, the forces of law and order caught up with the lawbreakers, while the US army defeated the Plains Indians. As homesteaders, hunters, miners and cattle ranchers flooded onto the Plains, they not only came into conflict with the Plains Indians who already lived there, but also with each other. -

61934 Inventory Nomination Form Date Entered 1. Name 5. Location Of

NPS Form 10-900 0MB No. 1024-0018 (3-82) Exp. 10-31-84 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service For NPS use only National Register of Historic Places received JUN _ 61934 Inventory Nomination Form date entered See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type ail entries complete applicable sections _______________________________ 1. Name historic New Mexican Pastor Sites in this Texas Panhandle and/or common none 2. Location see c»nE*nuation street & number sheets for specific locations of individual sites ( XJ not for publication city, town vicinity of Armstrong (Oil), Floyd (153), Hartley (205 state Texas code 048 county Qldham (359), Potter (375) code______ Category Ownership Status Present Use district public occupied agriculture museum building(s) private X unoccupied commercial park structure X both work in progress educational private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious object N/A jn process X yes: restricted government scientific X thematic being considered X yes: unrestricted industrial transportation no military X other- ranrh-f-ng 4. Owner of Property name see continuation sheets for individual sites street & number city, town JI/Avicinity of state Texas 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Armstrong, Floyd, Hartley, Oldham, and Potter County Courthouses street & number city, town Claude, Floydada, Channing, Vega, Amarillo state Texas 6. Representation in Existing Surveys Panhandle Pastores Survey title Panhandle Pastores -

Promise Beheld and the Limits of Place

Promise Beheld and the Limits of Place A Historic Resource Study of Carlsbad Caverns and Guadalupe Mountains National Parks and the Surrounding Areas By Hal K. Rothman Daniel Holder, Research Associate National Park Service, Southwest Regional Office Series Number Acknowledgments This book would not be possible without the full cooperation of the men and women working for the National Park Service, starting with the superintendents of the two parks, Frank Deckert at Carlsbad Caverns National Park and Larry Henderson at Guadalupe Mountains National Park. One of the true joys of writing about the park system is meeting the professionals who interpret, protect and preserve the nation’s treasures. Just as important are the librarians, archivists and researchers who assisted us at libraries in several states. There are too many to mention individuals, so all we can say is thank you to all those people who guided us through the catalogs, pulled books and documents for us, and filed them back away after we left. One individual who deserves special mention is Jed Howard of Carlsbad, who provided local insight into the area’s national parks. Through his position with the Southeastern New Mexico Historical Society, he supplied many of the photographs in this book. We sincerely appreciate all of his help. And finally, this book is the product of many sacrifices on the part of our families. This book is dedicated to LauraLee and Lucille, who gave us the time to write it, and Talia, Brent, and Megan, who provide the reasons for writing. Hal Rothman Dan Holder September 1998 i Executive Summary Located on the great Permian Uplift, the Guadalupe Mountains and Carlsbad Caverns national parks area is rich in prehistory and history. -

Jeremy L. Weiss

Jeremy L. Weiss, PhD Climate and Geospatial Extension Scientist School of Natural Resources and the Environment University of Arizona 1064 East Lowell Street Tucson, AZ 85721 (520) 626-8063 [email protected] Website: cals.arizona.edu/research/climategem LinkedIn: www.linkedin.com/in/jeremylweiss Twitter: @jeremylweiss HIGHER EDUCATION 2012 Doctor of Philosophy, University of Arizona • major: geosciences (climate dynamics) • minor: natural resources • advisor: Dr. Jonathan T. Overpeck • thesis: “Spatiotemporal Measures of Exposure and Sensitivity to Climatic Variability and Change: The Cases of Modern Sea Level Rise and Southwestern U.S. Bioclimate” 2002 Master of Science, University of New Mexico • major: earth and planetary sciences (climatology) • advisor: Dr. David S. Gutzler • thesis: “Relating Vegetation Variability to Meteorological Variables at the Sevilleta National Wildlife Refuge, New Mexico” 1998 Bachelor of Science, Arizona State University, summa cum laude major: botany (horticulture) minor: Spanish HONORS & AWARDS 2018 Laureate, Campus France “Make Our Planet Great Again – Short Stay Program” 2016 Environmental Research Letters 10th Anniversary Collection 2012 Galileo Circle Scholar 2010 Tony Gonzales Excellence in GIS Scholarship 2009 William G. McGinnies Scholarship in Arid Lands Studies 2002 Master of Science degree examination passed with distinction 2002 Geology Alumni Scholarship 2001 Jerry Harbour Memorial Scholarship 1998 Outstanding Graduating Senior Award, Department of Plant Biology 1997-1998 Mike Krantz Memorial Fund Scholarship 1996-1998 Dougherty Foundation Scholarship Award 1995 Phi Kappa Phi Honor Society 1993-1996 Award for Outstanding Scholarship 1993-1996 Hudson Achievement Award 1993-1996 Northern Arizona University Academic Award PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE 2014-present Climate and Geospatial Extension Scientist, University of Arizona Cooperative Extension, Tucson AZ 2013-2014 Research Scientist, University of Arizona, Tucson AZ 2012-2014 Scientific and Technical Consultant, Tucson AZ Jeremy L. -

On the Internal Border: Colonial Difference, the Cold War, and the Locations of "Underdevelopment" Alyosha Goldstein

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository American Studies Faculty and Staff ubP lications American Studies 2008 On the Internal Border: Colonial Difference, the Cold War, and the Locations of "Underdevelopment" Alyosha Goldstein Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/amst_fsp Recommended Citation Comparative Studies in Society and History 2008;50(1):26-56 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the American Studies at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in American Studies Faculty and Staff ubP lications by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Comparative Studies in Society and History 2008;50(1):26–56. 0010-4175/08 $15.00 # 2008 Society for Comparative Study of Society and History DOI: 10.1017/S0010417508000042 On the Internal Border: Colonial Difference, the Cold War, and the Locations of “Underdevelopment” ALYOSHA GOLDSTEIN American Studies, University of New Mexico In 1962, the recently established Peace Corps announced plans for an intensive field training initiative that would acclimate the agency’s burgeoning multitude of volunteers to the conditions of poverty in “underdeveloped” countries and immerse them in “foreign” cultures ostensibly similar to where they would be later stationed. This training was designed to be “as realistic as possible, to give volunteers a ‘feel’ of the situation they will face.” With this purpose in mind, the Second Annual Report of the Peace Corps recounted, “Trainees bound for social work in Colombian city slums were given on-the-job training in New York City’s Spanish Harlem...