Consecrating the Buddha : Legend, Lo Re,And History of the Imperial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beyond Buddhist Apology the Political Use of Buddhism by Emperor Wu of the Liang Dynasty

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Ghent University Academic Bibliography Beyond Buddhist Apology The Political Use of Buddhism by Emperor Wu of the Liang Dynasty (r.502-549) Tom De Rauw ii To my daughter Pauline, the most wonderful distraction one could ever wish for and to my grandfather, a cakravartin who ruled his own private universe iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Although the writing of a doctoral dissertation is an individual endeavour in nature, it certainly does not come about from the efforts of one individual alone. The present dissertation owes much of its existence to the help of the many people who have guided my research over the years. My heartfelt thanks, first of all, go to Dr. Ann Heirman, who supervised this thesis. Her patient guidance has been of invaluable help. Thanks also to Dr. Bart Dessein and Dr. Christophe Vielle for their help in steering this thesis in the right direction. I also thank Dr. Chen Jinhua, Dr. Andreas Janousch and Dr. Thomas Jansen for providing me with some of their research and for sharing their insights with me. My fellow students Dr. Mathieu Torck, Leslie De Vries, Mieke Matthyssen, Silke Geffcken, Evelien Vandenhaute, Esther Guggenmos, Gudrun Pinte and all my good friends who have lent me their listening ears, and have given steady support and encouragement. To my wife, who has had to endure an often absent-minded husband during these first years of marriage, I acknowledge a huge debt of gratitude. She was my mentor in all but the academic aspects of this thesis. -

Xiao Gang (503-551): His Life and Literature

Xiao Gang (503-551): His Life and Literature by Qingzhen Deng B.A., Guangzhou Foreign Language Institute, China, 1990 M.A., Kobe City University of Foreign Languages, Japan, 1996 Ph.D., Nara Women's University, Japan, 2001 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Doctor of Philosophy in The Faculty of Graduate Studies (Asian Studies) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) February 2013 © Qingzhen Deng, 2013 ii Abstract This dissertation focuses on an emperor-poet, Xiao Gang (503-551, r. 550-551), who lived during a period called the Six Dynasties in China. He was born a prince during the Liang Dynasty, became Crown Prince upon his older brother's death, and eventually succeeded to the crown after the Liang court had come under the control of a rebel named Hou Jing (d. 552). He was murdered by Hou before long and was posthumously given the title of "Emperor of Jianwen (Jianwen Di)" by his younger brother Xiao Yi (508-554). Xiao's writing of amorous poetry was blamed for the fall of the Liang Dynasty by Confucian scholars, and adverse criticism of his so-called "decadent" Palace Style Poetry has continued for centuries. By analyzing Xiao Gang within his own historical context, I am able to develop a more refined analysis of Xiao, who was a poet, a filial son, a caring brother, a sympathetic governor, and a literatus with broad and profound learning in history, religion and various literary genres. Fewer than half of Xiao's extant poems, not to mention his voluminous other writings and many of those that have been lost, can be characterized as "erotic" or "flowery". -

Preface of Selections of Refined Literature”

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 416 4th International Conference on Culture, Education and Economic Development of Modern Society (ICCESE 2020) Exploration on the Completion Time of the “Preface of Selections of Refined Literature” Yong Yu The College of Literature and Journalism Sichuan University Chengdu, China Abstract—The opinions on the completion time of the At the end of the "Preface of Selections of Refined "Preface of Selections of Refined Literature" have always been Literature", it describes the beginning year and end year of divergent and inconsistent. To examine its completion time, it the works collected in "Selections of Refined Literature" and is necessary to combine various internal and external factors the total number of volumes, and explains the basis of the such as the preface, the compilation style of "Selections of style order arrangement. Especially, the poems are Refined Literature", the life story of the editor, and the process subdivided into subtypes and sequenced according to the of writing the book. It helps to make clear the long-standing times. Obviously, it is neither possible for the editor to related disputes in the researches on "anthologizing presume the total number of volumes compiled before principles". completion of "Selections of Refined Literature" nor possible Keywords: “Preface of Selections of Refined Literature”, to previously have an idea of subdividing poems into Xiao Tong, completion time subtypes. If the "Preface of Selections of Refined Literature" was written in the compilation process but before completion I. INTRODUCTION of "Selections of Refined Literature", the editor would also not available to conclude that the total number of volumes is When was the "Preface of Selections of Refined thirty. -

Langdon Warner at Dunhuang: What Really Happened? by Justin M

ISSN 2152-7237 (print) ISSN 2153-2060 (online) The Silk Road Volume 11 2013 Contents In Memoriam ........................................................................................................................................................... [iii] Langdon Warner at Dunhuang: What Really Happened? by Justin M. Jacobs ............................................................................................................................ 1 Metallurgy and Technology of the Hunnic Gold Hoard from Nagyszéksós, by Alessandra Giumlia-Mair ......................................................................................................... 12 New Discoveries of Rock Art in Afghanistan’s Wakhan Corridor and Pamir: A Preliminary Study, by John Mock .................................................................................................................................. 36 On the Interpretation of Certain Images on Deer Stones, by Sergei S. Miniaev ....................................................................................................................... 54 Tamgas, a Code of the Steppes. Identity Marks and Writing among the Ancient Iranians, by Niccolò Manassero .................................................................................................................... 60 Some Observations on Depictions of Early Turkic Costume, by Sergey A. Yatsenko .................................................................................................................... 70 The Relations between China and India -

The Transparent Stone

WU HUNG The TransparentStone: Inverted Vision and Binary Imagery in Medieval Chinese Art A CRUCIAL MOMENT DIVIDES the course of Chinese art into two broad periods. Before this moment,a ritual art traditiontransformed general political and religious concepts into material symbols.Forms that we now call worksof art were integralparts of largermonumental complexes such as temples and tombs,and theircreators were anonymouscraftsmen whose individualcrea- tivitywas generallysubordinated to largercultural conventions. From the fourth and fifthcenturies on, however,there appeared a group of individuals-scholar- artistsand art critics-who began to forge theirown history.Although the con- structionof religiousand politicalmonuments never stopped, these men of let- ters attempted to transformpublic art into their private possessions, either physically,artistically, or spiritually.They developed a strongsentiment toward ruins,accumulated collectionsof antiques,placed miniaturemonuments in their houses and gardens,and "refined"common calligraphicand pictorialidioms into individual styles.This paper discusses new modes of writingand paintingat this liminalpoint in Chinese art history. Reversed Image and Inverted Vision Near the modern cityof Nanjing in eastern China, some ten mauso- leums survivingfrom the early sixth centurybear witnessto the past glory of emperors and princes of the Liang Dynasty(502-57).' The mausoleums share a general design (fig. 1). Three pairs of stone monumentsare usually erected in frontof the tumulus: a pair of stone animals-lions or qilinunicorns according to the statusof the dead-are placed before a gate formedby two stone pillars; the name and titleof the deceased appear on the flatpanels beneath the pillars' capitals. Finallytwo opposing memorialstelae bear identicalepitaphs recording the career and meritsof the dead person. -

The Evolution of the Story of the Wife of Emperor Wu of Liang in the Baojuan ∗ Texts of the Sixteenth–Nineteenth Centuries

《漢學研究》0254-4466 第 37 卷第 4 期 民國 108 年 12 月(2019.12)頁 159-203 漢學研究中心 Narrative of Salvation: The Evolution of the Story of the Wife of Emperor Wu of Liang in the Baojuan ∗ Texts of the Sixteenth–Nineteenth Centuries Rostislav Berezkin∗∗ Abstract The story of Emperor Wu of the Liang dynasty 梁武帝 (r. 502-549) rescuing his wife Lady Xi 郗氏 from an unfortunate rebirth as a snake was a common subject in popular literature related to Buddhist beliefs in late imperial China. Its history can be dated back to the twelfth century, when it quickly spread throughout the country. It is interpreted as a foundation of monastic Buddhist rites for the salvation of the dead, and it has also appeared as a narrative used in ritual storytelling and drama in several areas of China. Although Lady Xi’s story played a major role in the dissemination of Buddhist ideas and rituals among the common folk, its history and cultural impact still remain understudied. The present paper explores the development of Lady Xi’s story in the particular literary form of baojuan 寶卷 (precious scrolls) with the focus on performance traditions of southern Jiangsu. It compares three different Manuscript received: March 28, 2019; revision completed: May 6, 2019; approved: October 8, 2019. ∗ This research was assisted by a grant provided by the Chinese government foundation for research in social studies: “Survey and research on Chinese precious scrolls preserved abroad” 海外藏中國寶卷整理與研究 (17ZDA266). The author also expresses his gratitude to Paula Roberts for help with language issues. -

![Monks of the [Imperial] Family](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5779/monks-of-the-imperial-family-2935779.webp)

Monks of the [Imperial] Family

Tom De Rauw Ann Heirman (Ghent University) Monks for Hire: Liang Wudi’s use of Household Monks (jiaseng 家僧) Abstract Throughout history, Chinese monastic Buddhism has been characterised by a dichotomy between its religious ideal of austerity, and the factual wealth of its monasteries. While this contradiction often formed the basis for criticism on Buddhism and/or its institutions, it appeared to be unproblematic to most early Chinese Buddhist commentators, who frequently idealise the (conceptual) poverty of monks, whilst writing on the lavish adornments of their monasteries. The potential tension between an idealised detachment from material possession on the one hand and the accumulation of wealth on the other, was dissolved by making a distinction between the personal wealth of individual monks, and the collective wealth of the monastic community as a whole. However, during the reign of Liang Wudi 梁武帝 (r. 502-549), we see the emergence of an interesting form of personal financing of monks, namely the practice of imperially paid household monks (jiaseng 家僧). This paper investigates this unique clerical title, which did not last long after Emperor Wu’s reign. What were the motives for hiring monks on a personal basis and how did this tie in with Wu’s political use of Buddhism? Who were these monks, and what was their function? Was there any opposition against them on the basis of their payment? 2 I. Introduction When Liang Wudi 梁武帝 (r. 502-549) ascended the throne, he faced some major challenges. First was the problem of legitimacy. Emperor Wu had seized power from one of his kinsmen, Xiao Baorong 蕭寶融 (488-502), last emperor of the preceding Qi dynasty (479-502 CE), in revenge for the murder of his older brother. -

Download Article

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 233 3rd International Conference on Contemporary Education, Social Sciences and Humanities (ICCESSH 2018) An Investigation on the Creation and Existence of Yuefu Lyric Poetry of the Xianbei Regime during the Northern and Southern Dynasties* Xing Tang School of Liberal Arts Northwest Minzu University Lanzhou, China Abstract—During the period of the Northern and Southern Five Dynasties. Scholars paid much attention to Yuefu lyric Dynasties, the regimes of northern ethnic minority were poetry of the Northern Dynasties. However, the focus of everywhere. After the Xianbei nationality began to rise in the research has been on individual articles and important writers northeast, they turned to fight in the east and the west, and for a long time. In recent years, this situation has been established a number of independent regimes. They almost improved. However, there are still many problems that need crossed the entire period of the Northern Dynasties. With the further investigation. establishment of these Xianbei ethnic regimes, the Yuefu lyric poetry has both inherited and newly created in various political powers. It shows differences and uniqueness in the II. CREATION AND EXISTENCE OF YUEFU LYRIC POETRY subject matter, content, quantity, and ethnic composition of DURING FOEMER YAN TO NORTHERN WEI DYNASTY the author. And at the same time, it presents a certain degree The Yuefu lyric poetry created under Xianbei regime of of commonality and succession. South and North Dynasties should be "Agan Song" in Foemer Yan established by Murongwei. In "Jin Shu", Keywords—Southern and Northern Dynasties; Xianbei "Xianbei called the brother Agan, and Murongwei recalled it regime; Yuefu lyric poetry; creation; existence with a song of Agan"[1]. -

From Barbarians to the Middle Kingdom: the Rise of the Title “Emperor, Heavenly Qaghan” and Its Significance

From Barbarians to the Middle Kingdom: The Rise of the Title “Emperor, Heavenly Qaghan” and Its Significance Han-je Park* INTRODUCTION The entrance of the Five Barbarians wuhu( 五胡) people into the Central Plain of China is a historical event of great significance in the East, comparable in importance to the migration of Germanic tribes into the Roman Empire. The Five Barbarians became the main actors in the establishment of an array of dynasties throughout the periods of the Sixteen Kingdoms of Five Hu, the Northern Dynasties, and eventually the cosmopolitan empires of the Sui (隋) and the Tang (唐). With the passing of time, they lost their original culture and customs, and many came to lose their ethnonym. This phenomenon is described as their sinicization (hanhua 漢化), although there is also a contrary view that the Han (漢) people in China were barbaricized (huhua 胡化) and thus widened the range of Chinese culture. But, we may ask, do the terms “sinicization” and “barbaricization” adequately convey what really happened? Aside from arguments regarding sinicization or barbaricization, what role did the Five Barbarians actually play in the history of China? Were they indeed a people without a culture, who could therefore not bring anything novel to China itself,1 or were they a civilization with a sophisticated culture of their own? *Seoul National University (Seoul, Korea) Journal of Central Eurasian Studies, Volume 3 (October 2012): 23–68 © 2012 Center for Central Eurasian Studies 24 Han-je Park The Han and Tang empires are often joined together and referred to as the “empires of the Han and the Tang,” implying that these two dynasties have a great deal in common. -

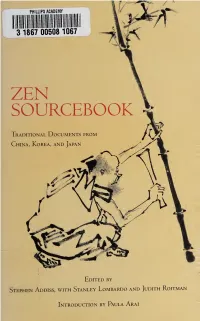

Zen Sourcebook

PHILLIPS ACAD ZEN SOURCEBOOK Traditional Documents from China, Korea, and Japan Edited by Stephen Addiss, with Stanley Lombardo and Judith Roitman Introduction by Paula Arai # C_yfnno 1778 • ft # # PHILLIPS • ACADEMY f> *# ##<*### #-^ass©iaSH!# % # # OLIVER - WEN DELL • HOLMES f># # # LIBRARY # # # # f>* # * ADAMS BOOK FUND ZEN SOURCEBOOK Traditional Documents from China, Korea,, Japan Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2019 with funding from Kahle/Austin Foundation https://archive.org/details/zensourcebooktraOOOOunse ZEN SOURCEBOOK Traditional Documents from China, Korea, japan Edited by Stephen Addiss With Stanley Lombardo and Judith Roitman Introduction by Paula Arai Hackett Publishing Company, Inc. Indianapolis/Cambridge GfT o '’HOB Copyright © 2008 by Hackett Publishing Company, Inc. All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America 14 13 12 11 10 09 08 123436 For further information, please address: Hackett Publishing Company, Inc. P.O. Box 44937 Indianapolis, IN 46244-0937 www.hackettpublishing.com Cover design by Abigail Coyle Text design by Meera Dash Composition by Agnews, Inc. Printed at Edwards Brothers, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Zen sourcebook : traditional documents from China, Korea, and Japan / edited by Stephen Addiss, with Stanley Lombardo and Judith Roitman ; introduction by Paula Arai. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN-13: 978-0-87220-909-1 (pbk.) ISBN-13: 978-0-87220-910-7 (cloth) 1. Zen Buddhism—Early works to 1800. 2. Zen literature. I. Addiss, Stephen, 1935- II. Lombardo, Stanley, 1943- III. Roitman, Judith, 1945- BQ9258.Z464 2008 294.3'927—dc22 2007038739 The paper used in this publication meets the minimum standard requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48—1984. -

Patronage and Community in Medieval China

INTRODUCTION 1 ONE INTRODUCTION This work seeks to explain the development of an important provincial society, the Xiangyang 襄陽 region (in modern northern Hubei province), and the terms on which its members interacted with representatives of the southern court at Jiankang 建康 in the fi fth and sixth centuries CE. It responds to the shortcomings of models of aristocracy and oligarchy , which have been applied to the social system of early medieval China, by demonstrating that a model based on patronage is far more helpful in understanding the tremendous instability of the political system, and the process of recruitment and assimilation of provincial leaders. It is the central thesis of this work that patronage is the most useful model with which to understand the general political organization of the southern dynasties. The work further seeks to understand the effect of patronage on local society and local culture. On this issue it responds to prior efforts to characterize local society as a fairly integrated community , one in which local elites developed a protective, nurturant community ethos, and for which local men felt a signifi cant sense of loyalty and identity. This idea is put to the test and found wanting. Instead, the evidence suggests that local society was extremely fragmented, with loyalties directed at narrowly defi ned familial ties or social subgroups. This fragmentation was perpetuated and accentuated by the patronage system, which persistently drew men’s loyalties up and out of their communities and into the affairs of imperial patrons; it also transmitted the fi erce succession rivalries of the imperial court into local affairs. -

Illusion and Illumination

Illusion and Illumination: A New Poetics of Seeing in Liang Dynasty Court Literature Author(s): Xiaofei Tian Source: Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies , Jun., 2005, Vol. 65, No. 1 (Jun., 2005), pp. 7-56 Published by: Harvard-Yenching Institute Stable URL: http://www.jstor.com/stable/25066762 REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: http://www.jstor.com/stable/25066762?seq=1&cid=pdf- reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies This content downloaded from 206.253.207.235 on Mon, 13 Jul 2020 17:55:52 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Illusion and Illumination: A New Poetics of Seeing in Liang Dynasty Court Literature XIAOFEI TIAN Harvard University PALACE (502-557) Style is a name poetry that was given(gongtishi to poetry written BII?Nf) by the of the Liang dynasty ig Crown Prince Xiao Gang UH (503-551) and his courtiers in the 530s and 540s. This poetry has long been misunderstood as deal ing primarily or even exclusively with the topics of women and romantic passions (yanqing BEflf).1 This paper proposes that we think of Palace Style poetry not only in terms of subject matter but also in terms of its formal aspects.