Howes Now Fall 2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inventory of American Sheet Music (1844-1949)

University of Dubuque / Charles C. Myers Library INVENTORY OF AMERICAN SHEET MUSIC (1844 – 1949) May 17, 2004 Introduction The Charles C. Myers Library at the University of Dubuque has a collection of 573 pieces of American sheet music (of which 17 are incomplete) housed in Special Collections and stored in acid free folders and boxes. The collection is organized in three categories: African American Music, Military Songs, and Popular Songs. There is also a bound volume of sheet music and a set of The Etude Music Magazine (32 items from 1932-1945). The African American music, consisting of 28 pieces, includes a number of selections from black minstrel shows such as “Richards and Pringle’s Famous Georgia Minstrels Songster and Musical Album” and “Lovin’ Sam (The Sheik of Alabami)”. There are also pieces of Dixieland and plantation music including “The Cotton Field Dance” and “Massa’s in the Cold Ground”. There are a few pieces of Jazz music and one Negro lullaby. The group of Military Songs contains 148 pieces of music, particularly songs from World War I and World War II. Different branches of the military are represented with such pieces as “The Army Air Corps”, “Bell Bottom Trousers”, and “G. I. Jive”. A few of the delightful titles in the Military Songs group include, “Belgium Dry Your Tears”, “Don’t Forget the Salvation Army (My Doughnut Girl)”, “General Pershing Will Cross the Rhine (Just Like Washington Crossed the Delaware)”, and “Hello Central! Give Me No Man’s Land”. There are also well known titles including “I’ll Be Home For Christmas (If Only In my Dreams)”. -

Early Life of Elizabeth Garrett

Library of Congress Early Life of Elizabeth Garrett Redfield Georgia B. FEB 15 1937 [?] 2/11/37 512 words Early Life of Elizabeth Garrett Given In An Interview. Feb. 9-1937 “As an ‘old-timer’-as you say-I will be glad to tell you anything you would like to hear of my life in our Sunshine State-New Mexico”; said Elizabeth Garrett in an appreciated interview graciously granted this writer. Appreciated because undue publicity of her splendid achievuments and of her private life, is avoided by this famous but unspoiled musician and composer. “My father, Pat Garrett came to Fort Sumner New Mexico in 1878. He and my mother, who was Polinari Gutierez Gutiernez , were married in Fort Sumner. “I”Was born at Eagle Creek, up above the Ruidoso in the White Mountain country. “We moved to Roswell (five miles east) while I was yet an infant. I have never been back to my birthplace but believe a lodge has been built on our old mountain home site. “You ask what I think of the Elizabeth Garrett bill presented at this session of the legislature? To grant me a monthly payment during my lifetime for what I have accomplished of the State Song, I think was a beautiful tho'ught. Early Life of Elizabeth Garrett http://www.loc.gov/resource/wpalh1.19181508 Library of Congress “I owe appreciation and thanks to New Mexico people and particulary to Grace T. Bear and to the “Club o' Ten” as the originators of the idea. If this bill is passed New Mexico will be the first state that has given such evidence of appreciation (in such a distinctive way) to a composer & autho'r of a State Song. -

Christopher A. Reynolds Collection of Women's Song

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt1t1nf085 No online items Inventory of the Christopher A. Reynolds Collection of Women's Song Sara Gunasekara & Jared Campbell Department of Special Collections General Library University of California, Davis Davis, CA 95616-5292 Phone: (530) 752-1621 Fax: (530) 754-5758 Email: [email protected] © 2013 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Inventory of the Christopher A. D-435 1 Reynolds Collection of Women's Song Collector: Reynolds, Christopher A. Title: Christopher A. Reynolds Collection of Women's Song Date (inclusive): circa 1800-1985 Extent: 15.3 linear feet Abstract: Christopher A. Reynolds, Professor of Music at the University of California, Davis, has identified and collected sheet music written by women composers active in North America and England. This collection contains over 3000 songs and song publications mostly published between 1850 and 1950. The collection is primarily made up of songs, but there are also many works for solo piano as well as anthems and part songs. In addition there are books written by the women song composers, a letter written by Virginia Gabriel in the 1860s, and four letters by Mrs. H.H.A. Beach to James Francis Cooke from the 1920s. Physical location: Researchers should contact Special Collections to request collections, as many are stored offsite. Repository: University of California, Davis. General Library. Dept. of Special Collections. Davis, California 95616-5292 Collection number: D-435 Language of Material: Collection materials in English Biography Christoper A. Reynolds received his PhD from Princeton University. He is Professor of Music at the University of Californa, Davis and author of Papal Patronage and the Music of St. -

Section IX the STATE PAGES

Section IX THE STATE PAGES THE FOLLOWING section presents information on all the states of the United States and the District of Columbia; the commonwealths of Puerto Rico and the Northern Mariana Islands; the territories of American Samoa, Guam and the Virgin Islands; and the United Na tions trusteeships of the Federated States of Micronesia, the Marshall Islands and the Republic of Belau.* Included are listings of various executive officials, the justices of the supreme courts and officers of the legislatures. Lists of all officials are as of late 1981 or early 1982. Comprehensive listings of state legislators and other state officials appear in other publications of The Council of State Governments. Concluding each state listing are population figures and other statistics provided by the U.S. Bureau of the Census, based on the 1980 enumerafion. Preceding the state pages are three tables. The first lists the official names of states, the state capitols with zip codes and the telephone numbers of state central switchboards. The second table presents historical data on all the states, commonwealths and territories. The third presents a compilation of selected state statistics from the state pages. *The Northern Mariana Islands, the Federated States of Micronesia, the Marshall Islands and the Republic of Belau (formerly Palau) have been administered by the United Slates since July 18, 1947, as part of the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands (TTPl), a trusteeship of the United Nations. The Northern Mariana Islands separated themselves from TTPI in March 1976 and now operate under a constitutional govern ment instituted January 9, 1978. -

New Mexico Musician Vol 58 No 3 (Spring 2011)

New Mexico Musician Volume 58 | Number 3 Article 1 4-1-2011 New Mexico Musician Vol 58 No 3 (Spring 2011) Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nm_musician Part of the Music Education Commons Recommended Citation . "New Mexico Musician Vol 58 No 3 (Spring 2011)." New Mexico Musician 58, 3 (2011). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/ nm_musician/vol58/iss3/1 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in New Mexico Musician by an authorized editor of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ·.:.��!.�� Look Forward To Practice! You spend so much time practicing, you really should enjoy it. That's why Yamaha created the SV-150 Silent Practice Plus vmlin It feels. plays and sounds like an acoustic violin but it's got some maior advantages.. The SV-150 comes with a music player/controller that can hold gigabytes of your favorite songs and performance pieces Play along with them and listen-in privacy-through headphones You can slow down any song to learnit. or speed 11 up for a challenge.• The SV-150's violin tone is rich and natural Use the 24 included digital effects to sweeten it up and create any sound you want. • Last but not least. the SV-150 packs a tuner and metronome in the controller, it's everything you need in one package • Visit yamahastrings.com to learn more about the SV-150 and to find a dealer near you Practice will never be dull again Saveyour favonte Ad1ust the 1empo MP3,WAV. -

New Mexico Daily Lobo, Volume 075, No 95, 2/23/1972." 75, 95 (1972)

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository 1972 The aiD ly Lobo 1971 - 1980 2-23-1972 New Mexico Daily Lobo, Volume 075, No 95, 2/ 23/1972 University of New Mexico Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/daily_lobo_1972 Recommended Citation University of New Mexico. "New Mexico Daily Lobo, Volume 075, No 95, 2/23/1972." 75, 95 (1972). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/daily_lobo_1972/24 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the The aiD ly Lobo 1971 - 1980 at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in 1972 by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. _______________________________ , ___ -- ------·- Nixon-Chou Meeting Longer Than Expected Pat Enjoys First Sightseeing PEKING (U;t>I)- President the cultul'al revolutiou that shook Pt<H>ident might have another radio, v,rhich had paid little coverage, told UPI he assumed the Nixon and Premier Chou En· Lai China in the late 1960s. meeting with Communist Party attention to the visit previously, press had waited until Tuesday conferred in strict secrecy for White Hou&e Press Secretary Chairman Mao Tse-Tung whom he suddenly gave it a big splash on ''in order that our American three hours and 50 minutes Ronald Ziegler smiled broadly as saw on Monday a short time after Tuesday. A new atmosphere of friends might have the Tuesday as the governmept press he fend~d off all questions about his arrival in Peking. relaxation and friendliness marked opportunity to publish the and Chinese people ~ as if on cue the substance of the second The talks Tuesday, which Chou newsmen's contacts with pictures first in their papers." from Mao Tse·Tung - suddenly extended session between Nixon has said he hoped would be "a government press aides, The unprecedented Chinese warmed to their search for and Chou, referring newsmen to frank exchange of views between department store clerks and coverage of the visit made it clear reconciliation. -

America's Majestic National Parks

America’s Majestic National Parks LAND TOUR Plus optional extensions in: The Dakota Badlands New Mexico: Albuquerque, Taos & Santa Fe 2016 Grand Circle Travel Handbook America’s Majestic National Parks Table of Contents 1. YOUR HEALTH ..................................................................................................................................... 3 Keep Your Abilities In Mind ................................................................................................................... 3 Health Check ............................................................................................................................................ 4 High Altitude ........................................................................................................................................... 4 Prescription Medications ......................................................................................................................... 4 2. LUGGAGE REGULATIONS & AIR TRAVEL ................................................................................. 5 Luggage Limits ........................................................................................................................................ 5 Luggage Suggestions ............................................................................................................................... 6 Airport Security/TSA ............................................................................................................................... 6 Airport -

Business Boom in Downtown Clovis ❏ Breweries, Fitness Center Among Businesses Moving In

WEEKEND EDITION SUNDAY,AUG. 23, 2020 Inside: $1.50 Livestock sale still open for donations — Page 6A Vol. 92 ◆ No. 42 SERVING CLOVIS, PORTALES AND THE SURROUNDING COMMUNITIES EasternNewMexicoNews.com Business boom in downtown Clovis ❏ Breweries, fitness center among businesses moving in. By Lily Martin STAFF WRITER [email protected] CLOVIS — From breweries to fitness cen- ters, downtown Clovis is seeing a surge of incoming businesses as old buildings on and around Main Street are being renovated to house new endeavors. Range Movement opened its doors in April as founders Brooke McDonald and Meg Crawford combined childcare and fitness to create a unique workout space. Staff photo: Kevin Wilson “We are a fitness studio specializing in small Cowboys for Trump leads a parade north along Prince Street in Clovis Saturday morning. The group, along with Bikers for group classes. We do everything from strength, Trump, held an event that was part rally and part protest at the Lowe’s parking lot and Ned Houk Park. HIIT, yoga, barre, and recovery,” McDonald said. Along with adult classes, Range Movement also has “mini-ranger” classes for kids during Cowboys push for Trump support popular workout times. While parents are working out, their kids can be playing safely ❏ Couy Griffin: the park about various topics, nearby, making their workouts more accessible most notably the need for the to parents and caretakers. ‘Silent majority needs "silent majority" to elect Trump “We like the downtown area, we wanted to and other conservative leaders. kind of help bring some business to it,” to be a little louder.’ “It’s become necessary the McDonald said. -

Western Liberal, 03-24-1916 Lordsburg Print Company

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Lordsburg Western Liberal, 1889-1918 New Mexico Historical Newspapers 3-24-1916 Western Liberal, 03-24-1916 Lordsburg Print Company Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/lwl_news Recommended Citation Lordsburg Print Company. "Western Liberal, 03-24-1916." (1916). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/lwl_news/919 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the New Mexico Historical Newspapers at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Lordsburg Western Liberal, 1889-1918 by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i I .J LU K ! i) .i 1L üiliO WEST LldlL .A. Volume XXIX No. 19 Lordsburg, New BUMcnrnoN, m rs Mexico, Friday, March 24, 1916 SINCLB COPIES, TENmCUITO DEATH OF BENJ. TITUS v ROAD WORK DONE1 MINES AND MINING SOCIAL EVENTS Another of Lordsburg's False Reports Ho! to the boys of the 85 Mine. St Patrick '8 Day " in the eve-ni- n' On Saturday evening at the 85 "pioneers has answered the call " of the Grim Reaper. Benjamin The Grant County road workers SELLS TUNGSTEN rROERTY Following, the Liberal is pub- was very appropriately Mine Theatre, the "boys" of our Titus, for twenty years manager have completed the new Border- One of the most important min- lishing an article appearing in celebrated by a large crowd of prosperous mining camp to the of the Binn Lumber Company land Route, going directly west ing transactions of the past few the Los Anéeles Examiner both old and young of Lordsburg south gave a dance. -

New Mexico State Record, 03-09-1917 State Publishing Company

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository New Mexico State Record, 1916-1921 New Mexico Historical Newspapers 3-9-1917 New Mexico State Record, 03-09-1917 State Publishing Company Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nm_state_record_news Recommended Citation State Publishing Company. "New Mexico State Record, 03-09-1917." (1917). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/ nm_state_record_news/35 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the New Mexico Historical Newspapers at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in New Mexico State Record, 1916-1921 by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NEW MEXICO STATE jRECORD 31.50 A YEAR. SANTA FE, NEW MEXICO FRIDAY, MARCH 9, 1917. NUMBER 128 claimed to be an attribute of this OPUflfll AC IlltJCC principles expounded from the back, session Even the time honored Us" bone of our civilization. MEMORY OF LATE FEDERAL - jOllilUUL MINtO POWDER THIRD STATE LEGISLATURE 31ipJljr Mill WAS jJdICU UWWU III U1J3- Any system of education that fails iness basis, and there were very few to teach child who did the how to earn his employees not earn their GEOLOGIC SURVEY bread and butter is worse than no GOVERNOR OBSERVED money In fact there were some FACTORY IS NOT system. Specialization is the magic HAS PASSED INTO HISTORY employees who did enough extra to success wotk at the rate of key and it matters but pay prescribed little whether the controlling fac- BY I j make up for deficiencies in this IS NOW ESSENTIAL tor be brain or brawn. -

Official Scenic Historic Marker Program Application Form

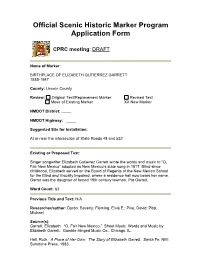

Official Scenic Historic Marker Program Application Form CPRC meeting: DRAFT Name of Marker: BIRTHPLACE OF ELIZABETH GUTIERREZ GARRETT 1885-1947 County: Lincoln County Review: Original Text/Replacement Marker Revised Text Move of Existing Marker XX New Marker NMDOT District: NMDOT Highway: Suggested Site for Installation: At or near the intersection of State Roads 48 and 532 Existing or Proposed Text: Singer songwriter Elizabeth Gutierrez Garrett wrote the words and music to “O, Fair New Mexico” adopted as New Mexico’s state song in 1917. Blind since childhood, Elizabeth served on the Board of Regents of the New Mexico School for the Blind and Visually Impaired, where a residence hall now bears her name. Garret was the daughter of famed 19th century lawman, Pat Garrett. Word Count: 63 Previous Title and Text: N/A Researcher/author: Duran, Beverly; Fleming, Elvis E.; Pike, David; Pital, Michael Source(s): Garrett, Elizabeth. “O, Fair New Mexico.” Sheet Music. Words and Music by Elizabeth Garrett. Gamble Hinged Music Co., Chicago, IL. Hall, Ruth. A Place of Her Own: The Story of Elizabeth Garrett. Santa Fe, NM: Sunstone Press, 1983. Melzer, Richard, Ph.D. Buried Treasures. Santa Fe, NM: Sunstone Press, 2007. Metz, Leon Claire. Pat Garrett: The Story of a Western Lawman. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1972. Redfield, Georgia B. “Early Life of Elizabeth Garrett.” Works Progress Administration Interview, February 9, 1937. Redfield, Georgia B. “Elizabeth Garrett. Works Progress Administration Interview January 13, 1939. Weigle, Marta and Peter White. The Lore of New Mexico. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press, 2005. Text Approved by CPRC on Date: CPRC Comments: For Referral to: . -

Message from the President National Book Festival

Volume 48, Issue 5 September/October 2018 Inside this issue: Message from the President Eli Guinnee Returns 2 Dr. John Sandstrom, NMLA President, [email protected] to New Mexico January/February 2016 Funding for Library 3 Happy Fall! We are gearing up for our Annual Conference, Completing the Circle, and it looks Broadband like a good time will be had by all. UNM University 4 Wednesday starts with a great line-up of pre-conferences, including Mary Keeling, AASO Libraries News President-Elect, and the day ends with the Opening Reception with the Vendors at 4:30 pm. In light of it being Halloween, I hope you all will join me in dressing for the occasion. Who knows, NMSU Library 5 there may even be some prizes. News Proposal to Fund 6 Thursday starts with our Keynote Speaker, Jim Neal, Immediate Past-President of the American Rural Libraries Library Association (http://tinyurl.com/nmla2018) and finishes with our Annual Awards Banquet. Remember that it isn’t too late to nominate people for our annual awards (https://nmla.org/ awards-honors/). NMLA Continuing 6 Education Grants There is a huge variety of great programming on Thursday and Friday aimed at all types of libraries. This will also be a chance to meet the folks on the State Library Commission as well as Four Corner 7 meeting the new State Librarian, Eli Guinnee. And don’t forget our President’s Luncheon on Storytelling Friday, featuring John Chrastka, Executive Director of EveryLibrary, speaking on positioning your library for advocacy success. 2018 Go Bond 7 In other news, ballots for electing the 2019 officers will be out soon.