BOOK REVIEWS Adorno's Aesthetic Theory Is

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NATURE, SOCIOLOGY, and the FRANKFURT SCHOOL by Ryan

NATURE, SOCIOLOGY, AND THE FRANKFURT SCHOOL By Ryan Gunderson A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Sociology – Doctor of Philosophy 2014 ABSTRACT NATURE, SOCIOLOGY, AND THE FRANKFURT SCHOOL By Ryan Gunderson Through a systematic analysis of the works of Max Horkheimer, Theodor W. Adorno, Herbert Marcuse, and Erich Fromm using historical methods, I document how early critical theory can conceptually and theoretically inform sociological examinations of human-nature relations. Currently, the first-generation Frankfurt School’s work is largely absent from and criticized in environmental sociology. I address this gap in the literature through a series of articles. One line of analysis establishes how the theories of Horkheimer, Adorno, and Marcuse are applicable to central topics and debates in environmental sociology. A second line of analysis examines how the Frankfurt School’s explanatory and normative theories of human- animal relations can inform sociological animal studies. The third line examines the place of nature in Fromm’s social psychology and sociology, focusing on his personality theory’s notion of “biophilia.” Dedicated to 바다. See you soon. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I owe my dissertation committee immense gratitude for offering persistent intellectual and emotional support. Linda Kalof overflows with kindness and her gentle presence continually put my mind at ease. It was an honor to be the mentee of a distinguished scholar foundational to the formation of animal studies. Tom Dietz is the most cheerful person I have ever met and, as the first environmental sociologist to integrate ideas from critical theory with a bottomless knowledge of the environmental social sciences, his insights have been invaluable. -

Hansen, Cinema and Experience: Siegfried Kracauer, Walter

Cinema and Experience WEIMAR AND NOW: GERMAN CULTURAL CRITICISM Edward Dimendberg, Martin Jay, and Anton Kaes, General Editors Cinema and Experience Siegfried Kracauer, Walter Benjamin, and Th eodor W. Adorno Miriam Bratu Hansen UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS Berkeley Los Angeles London University of California Press, one of the most distinguished university presses in the United States, enriches lives around the world by advancing scholarship in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. Its activities are supported by the UC Press Foundation and by philanthropic contributions from individuals and institutions. For more information, visit www.ucpress.edu. University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England © 2012 by Th e Regents of the University of California Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Hansen, Marian Bratu, 1949–2011. Cinema and experience : Siegfried Kracauer, Walter Benjamin, and Th eodor W. Adorno / Miriam Bratu Hansen. p. cm.—(Weimar and now: German cultural criticism ; 44) Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 978-0-520-26559-2 (cloth : alk. paper) isbn 978-0-520-26560-8 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Motion pictures. 2. Kracauer, Siegfried, 1889–1966—Criticism and interpretation. 3. Benjamin, Walter, 1892–1940—Criticism and interpretation. 4. Adorno, Th eodor W., 1903–1969—Criticism and interpretation. I. Title. PN1994.H265 2012 791.4309—dc23 2011017754 Manufactured in the United States of America 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 In keeping with a commitment to support environmentally responsible and sustainable printing practices, UC Press has printed this book on Rolland Enviro100, a 100 percent postconsumer fi ber paper that is FSC certifi ed, deinked, processed chlorine-free, and manufactured with renewable biogas energy. -

University of Oklahoma Graduate College

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by SHAREOK repository UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE THE LIFE AND WORK OF GRETEL KARPLUS/ADORNO: HER CONTRIBUTIONS TO FRANKFURT SCHOOL THEORY A Dissertation SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of P hilosophy BY STACI LYNN VON BOECKMANN Norman, Oklahoma 2004 UMI Number: 3147180 UMI Microform 3147180 Copyright 2005 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106-1346 THE LIFE AND WORK OF GRETEL KARPLUS/ADORNO: HER CONTRIBUTIONS TO FRANKFURT SCHOOL THEORY A Dissertation APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH BY ____________________________ _ Prof. Catherine Hobbs (Chair) _____________________________ Prof. David Gross ____________________________ _ Assoc. Prof. Susan Kates _____________________________ Prof. Helga Madland _____________________________ Assoc. Prof. Henry McDonald © Copyright by Staci Lynn von Boeckmann 2004 All Rights Reserved To the memory of my grandmother, Norma Lee Von Boeckman iv Acknowledgements There a number of people and institutions whose contributions to my work I would like to acknowledge. For the encouragement that came from being made a Fulbright Alternative in 1996, I would like to thank t he Fulbright selection committee at the University of Oklahoma. I would like to thank the American Association of University Women for a grant in 1997 -98, which allowed me to extend my research stay in Frankfurt am Main. -

Adorno, the Essay and the Gesture of Aesthetic Experience Estetika, 50(2): 149-168

http://www.diva-portal.org This is the published version of a paper published in Estetika. Citation for the original published paper (version of record): Johansson, A S. (2013) The Necessity of Over-interpretation: Adorno, the Essay and the Gesture of Aesthetic Experience Estetika, 50(2): 149-168 Access to the published version may require subscription. N.B. When citing this work, cite the original published paper. Permanent link to this version: http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:miun:diva-30068 Zlom2_2013_Sestava 1 1.10.13 13:28 Stránka 149 Anders Johansson THE NECESSITY OF OVER-INTERPRETATION: ADORNO, THE ESSAY AND THE GESTURE OF AESTHETIC EXPERIENCE ANDERS JOHANSSON This article is a discussion of Theodor W. Adorno’s comment, in the beginning of ‘The Essay as Form’, that interpretations of essays are over-interpretations. I argue that this statement is programmatic, and should be understood in the light of Adorno’s essayistic ideal of configuration, his notion of truth, and his idea of the enigmatic character of art. In order to reveal how this over-interpreting appears in practice, I turn to Adorno’s essay on Kafka. According to Adorno, the reader of Kafka is caught in an aporia: Kafka’s work cannot be interpreted, yet every single sentence calls for interpretation. This paradox is related to the gestures and images in Kafka’s work: like Walter Benjamin, Adorno means that they contain sedimented, forgotten experiences. Instead of interpreting these images, Adorno visualizes the experiences indirectly by presenting images of his own. His own essay becomes gestural. -

Absolute Relativity: Weimar Cinema and the Crisis of Historicism By

Absolute Relativity: Weimar Cinema and the Crisis of Historicism by Nicholas Walter Baer A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Media and the Designated Emphasis in Critical Theory in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Anton Kaes, Chair Professor Martin Jay Professor Linda Williams Fall 2015 Absolute Relativity: Weimar Cinema and the Crisis of Historicism © 2015 by Nicholas Walter Baer Abstract Absolute Relativity: Weimar Cinema and the Crisis of Historicism by Nicholas Walter Baer Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Media Designated Emphasis in Critical Theory University of California, Berkeley Professor Anton Kaes, Chair This dissertation intervenes in the extensive literature within Cinema and Media Studies on the relationship between film and history. Challenging apparatus theory of the 1970s, which had presumed a basic uniformity and historical continuity in cinematic style and spectatorship, the ‘historical turn’ of recent decades has prompted greater attention to transformations in technology and modes of sensory perception and experience. In my view, while film scholarship has subsequently emphasized the historicity of moving images, from their conditions of production to their contexts of reception, it has all too often left the very concept of history underexamined and insufficiently historicized. In my project, I propose a more reflexive model of historiography—one that acknowledges shifts in conceptions of time and history—as well as an approach to studying film in conjunction with historical-philosophical concerns. My project stages this intervention through a close examination of the ‘crisis of historicism,’ which was widely diagnosed by German-speaking intellectuals in the interwar period. -

10595.Ch01.Pdf

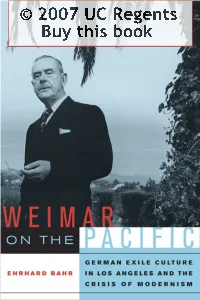

© 2007 UC Regents Buy this book University of California Press, one of the most distin- guished university presses in the United States, enriches lives around the world by advancing scholarship in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. Its ac- tivities are supported by the UC Press Foundation and by philanthropic contributions from individuals and in- stitutions. For more information, visit www.ucpress.edu. University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England © 2007 by The Regents of the University of California Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bahr, Ehrhard. Weimar on the Pacific : German exile culture in Los Angeles and the crisis of modernism / Ehrhard Bahr. p. cm.—(Weimar and now : 41) Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 978-0-520-25128-1 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Modern (Aesthetics)—California—Los Angeles. 2. German—California—Los Angeles—Intellectual life. 3. Jews. German—California—Los Angeles—Intellec- tual life. 4. Los Angeles (Calif.)—Intellectual life— 20th century. I. Title. bh301.m54b34 2007 700.89'31079494—dc22 200700207 Manufactured in the United States of America 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 09 08 07 10 987654321 The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of ansi/niso z39.48-1992 (r 1997) (Permanence of Paper). Contents List of Illustrations vii List of Abbreviations ix Preface xiii Introduction 1 1. The Dialectic of Modernism 30 2. Art and Its Resistance to Society: Theodor W. Adorno’s Aesthetic Theory 56 3. Bertolt Brecht’s California Poetry: Mimesis or Modernism? 79 4. The Dialectic of Modern Science: Brecht’s Galileo 105 5. -

Adorno's Politics

This is the penultimate draft; the final version appears in Philosophy & Social Criticism 40.9 (November 2014): http://psc.sagepub.com/content/early/2014/08/05/0191453714545198.abstract; please cite that version. Adorno’s Politics: Theory and Praxis in Germany’s 1960s∗ Fabian Freyenhagen University of Essex [email protected] Adorno inspired much of Germany’s 1960s student movement, but he came increasingly into conflict with this movement about the practical implications of his critical theory. As early as 1964, student activist lamented what they saw as an unbearable discrepancy between his analysis and his actions.1 As one of his PhD students later expressed it: […] Adorno was incapable of transforming his private compassion towards the “damned of the earth” into an organized partisanship of theory engaged in the liberation of the oppressed. […] his critical option that any philosophy if it is to be true must be immanently oriented towards practical transformation of social reality, loses its binding force if it is not also capable of defining itself in organizational categories. […] Detachment […] drove Adorno […] into complicity with the ruling powers. […]. As he moved more and more away from historical ∗ This article was originally conceived as part of my Adorno’s Practical Philosophy (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), and should be considered as integral to it. My thanks go to all of those who have commented on earlier drafts, especially Gordon Finlayson, Raymond Geuss, Béatrice Han-Pile. Patrice Maniglier, Richard Raatzsch, Jörg Schaub, Dan Swain, and Dan Watts. 1 For example, they produced leaflets with passages from Adorno’s own work – passages such as the following: “There can be no covenant with this world; we belong to it only to the extent that we rebel against it” – and invited students to contact Adorno to complain that he did not act accordingly (see Esther Leslie, ‘Introduction to Adorno/Marcuse Correspondence on the German Student Movement’, New Left Review I/233, January- February 1999, pp. -

Adorno and Ethics

Introduction: Adorno and Ethics Christina Gerhardt Interest in the writings of Theodor W. Adorno has increased over the past decade. To some extent this can be attributed to the fact that Adorno’s writings are now accessible to a wider audience, since more of his works have appeared in English translation over the past ten years.1 New translations of texts that were previously available in English but widely deemed inadequate have also I would like to thank Martin Jay and Tony Kaes for their unwavering support in the organization both of the conference and of this publication. Anson Rabinbach and Andrew Oppenheimer, one of New German Critique’s editors and its managing editor, respectively, have been consistently help- ful throughout the publication process, particularly as the journal has begun publication anew with Duke University Press. It is a tremendous honor for this issue to have been chosen to appear first in this new configuration, or constellation, as Adorno—drawing on Benjamin—would have said. 1. See Theodor W. Adorno, Beethoven: The Philosophy of Music, ed. Rolf Tiedemann, trans. Edmund Jephcott (Cambridge: Polity, 1998); Theodor W. Adorno and Walter Benjamin, The Com- plete Correspondence, 1928–1940, ed. Henri Lonitz, trans. Nicholas Walker (Cambridge, MA: Har- vard University Press, 1999); Theodor W. Adorno, Critical Models: Interventions and Catchwords, trans. Henry W. Pickford (New York: Columbia University Press, 1998); Adorno, Essays on Music, ed. Richard D. Leppert, trans. Susan H. Gillespie (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002); Adorno, Introduction to Sociology, ed. Christoph Gödde, trans. Edmund Jephcott (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2000); Adorno, Kant’s “Critique of Pure Reason,” ed. -

Theodor W. Adorno's Struggle with the Concept

BETWEEN MODERN AND POSTMODERN WORLDS: THEODOR W. ADORNO’S STRUGGLE WITH THE CONCEPT OF MUSICAL KITSCH Molly L. Barnes A thesis submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Music. Chapel Hill 2012 Approved by: Advisor: Felix Wörner Reader: Tim Carter Reader: Jon Finson © 2012 Molly L. Barnes ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT MOLLY L. BARNES: Between Modern and Postmodern Worlds: Theodor W. Adorno’s Struggle with the Concept of Musical Kitsch (Under the direction of Felix Wörner) The concept of “kitsch” remains a perennial concern for philosophers of aesthetics. Many distinguished writers have contributed to the literature on kitsch, yet the valuable work of the musicologist, sociologist, and philosopher Theodor Adorno (1903-1969) has been largely overlooked. Adorno nurtured an abiding interest in the topic of musical kitsch in particular, but was profoundly troubled by its implications for the cultural edification and psychological health of modern society. His writings also indicate that his ambivalence regarding kitsch became more acute with time. Through a close study of four texts by Adorno, including his analyses of specific musical works, I propose that Adorno’s increasingly conflicted attitude toward musical kitsch reflects growing tensions between modernist and postmodernist cultural perspectives in the mid-twentieth century, tensions that have persisted strongly into the twenty-first century. Indeed, Adorno’s thoughts regarding kitsch may help us understand musical aesthetics in his era as well as our own. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I have many people to thank for their help in bringing this thesis to completion. -

Walter Benjamin and the Aesthetics of Film Walter Benjamin and the Aesthetics of Film

Mourenza Walter Benjamin and the Aesthetics of Film Daniel Mourenza Walter Benjamin and the Aesthetics of Film the and Benjamin Walter FOR PRIVATE AND NON-COMMERCIAL USE AMSTERDAM UNIVERSITY PRESS Walter Benjamin and the Aesthetics of Film FOR PRIVATE AND NON-COMMERCIAL USE AMSTERDAM UNIVERSITY PRESS Walter Benjamin and the Aesthetics of Film Daniel Mourenza Amsterdam University Press FOR PRIVATE AND NON-COMMERCIAL USE AMSTERDAM UNIVERSITY PRESS Cover illustration: From left to right: Margot von Brentano, Valentina Kurella, Walter Ben- jamin, Gustav Glück, Bianca Minotti, Bernard von Brentano, Elisabeth Hauptmann. Berlin, New Year’s Eve 1931. Source: Akademie der Künste, Berlin, Elisabeth-Hauptmann-Archiv 758. Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout isbn 978 94 6298 017 4 e-isbn 978 90 4852 935 3 doi 10.5117/9789462980174 nur 670 © D. Mourenza / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2020 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. FOR PRIVATE AND NON-COMMERCIAL USE AMSTERDAM UNIVERSITY PRESS To Jan Sieber (1982–2018), in memoriam FOR PRIVATE AND NON-COMMERCIAL USE AMSTERDAM UNIVERSITY PRESS Acknowledgements I am very grateful to a number of individuals who have contributed directly or indirectly to the completion of this book, a project that began around 2010. I am especially grateful to the School of Fine Art, History of Art and Cultural Studies at the University of Leeds. -

Adorno's Politics: Theory and Praxis in Germany's 1960S∗

This is the penultimate draft; the final version appears in Philosophy & Social Criticism 40.9 (November 2014): http://psc.sagepub.com/content/early/2014/08/05/0191453714545198.abstract; please cite that version. Adorno’s Politics: Theory and Praxis in Germany’s 1960s∗ Fabian Freyenhagen University of Essex [email protected] Adorno inspired much of Germany’s 1960s student movement, but he came increasingly into conflict with this movement about the practical implications of his critical theory. As early as 1964, student activist lamented what they saw as an unbearable discrepancy between his analysis and his actions.1 As one of his PhD students later expressed it: […] Adorno was incapable of transforming his private compassion towards the “damned of the earth” into an organized partisanship of theory engaged in the liberation of the oppressed. […] his critical option that any philosophy if it is to be true must be immanently oriented towards practical transformation of social reality, loses its binding force if it is not also capable of defining itself in organizational categories. […] Detachment […] drove Adorno […] into complicity with the ruling powers. […]. As he moved more and more away from historical ∗ This article was originally conceived as part of my Adorno’s Practical Philosophy (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), and should be considered as integral to it. My thanks go to all of those who have commented on earlier drafts, especially Gordon Finlayson, Raymond Geuss, Béatrice Han-Pile. Patrice Maniglier, Richard Raatzsch, Jörg Schaub, Dan Swain, and Dan Watts. 1 For example, they produced leaflets with passages from Adorno’s own work – passages such as the following: “There can be no covenant with this world; we belong to it only to the extent that we rebel against it” – and invited students to contact Adorno to complain that he did not act accordingly (see Esther Leslie, ‘Introduction to Adorno/Marcuse Correspondence on the German Student Movement’, New Left Review I/233, January- February 1999, pp. -

Art and Aesthetics After Adorno

The Townsend Pa P e r s i n T h e h u m a n i T i e s No. 3 Art and Aesthetics After Adorno Jay M. Bernstein Claudia Brodsky Anthony J. Cascardi Thierry de Duve Aleš Erjavec Robert Kaufman Fred Rush Art and Aesthetics After Adorno The Townsend Pa P e r s i n T h e h u m a n i T i e s No. 3 Art and Aesthetics After Adorno J. M. Bernstein Claudia Brodsky Anthony J. Cascardi Thierry de Duve Aleš Erjavec Robert Kaufman Fred Rush Published by The Townsend Center for the Humanities University of California | Berkeley Distributed by University of California Press Berkeley, Los Angeles, London | 2010 Copyright ©2010 The Regents of the University of California ISBN 978-0-9823294-2-9 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Art and aesthetics after Adorno / J. M. Bernstein...[et al]. p. cm. — (The Townsend papers in the humanities ; no. 3) ISBN 978-0-9823294-2-9 1. Aesthetics, Modern—20th century 2. Aesthetics, Modern—21st century 3. Adorno, Theodor W., 1903–1969. Ästhetische Theorie. I. Bernstein, J. M. BH201.A78 2010 111’.850904—dc22 2010018448 Inquiries concerning proposals for the Townsend Papers in the Humanities from Berkeley faculty and Townsend Center affiliates should be addressed to The Townsend Papers, 220 Stephens Hall, UC Berkeley, Berkeley, CA 94720- 2340, or by email to [email protected]. Design and typesetting: Kajun Graphics Manufactured in the United States of America Credits and acknowledgements for quoted material appear on page 180–81.