George Ferrers and the Historian As Moral Compass.” LATCH 2 (2009): 101-114

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2 the Seven Deadly Sins</Em>

Early Theatre 10.1 (2007) ROBERT HORNBACK The Reasons of Misrule Revisited: Evangelical Appropriations of Carnival in Tudor Revels Undoubtedly the most arresting Tudor likeness in the National Portrait Gallery, London, is William Scrots’s anamorphosis (NPG1299). As if mod- eled after a funhouse mirror reflection, this colorful oil on panel painting depicts within a stretched oblong, framed within a thin horizontal rectangle, the profile of a child with red hair and a head far wider than it is tall; measur- ing 63 inches x 16 ¾ inches, the portrait itself is, the Gallery website reports, its ‘squattest’ (‘nearly 4 times wider than it is high’). Its short-lived sitter’s nose juts out, Pinocchio-like, under a low bump of overhanging brow, as the chin recedes cartoonishly under a marked overbite. The subject thus seems to prefigure the whimsical grotesques of Inigo Jones’s antimasques decades later rather than to depict, as it does, the heir apparent of Henry VIII. Such is underrated Flemish master Scrots’s tour de force portrait of a nine-year-old Prince Edward in 1546, a year before his accession. As the NPG website ex- plains, ‘[Edward] is shown in distorted perspective (anamorphosis) …. When viewed from the right,’ however, ie, from a small cut-out in that side of the frame, he can be ‘seen in correct perspective’.1 I want to suggest that this de- lightful anamorphic image, coupled with the Gallery’s dry commentary, pro- vides an ironic but apt metaphor for the critical tradition addressing Edward’s reign and its theatrical spectacle: only when viewed from a one-sided point of view – in hindsight, from the anachronistic vantage point of an Anglo-Amer- ican tradition inflected by subsequent protestantism – can the boy king, his often riotous court spectacle, and mid-Tudor evangelicals in general be made to resemble a ‘correct’ portrait of the protestant sobriety, indeed the dour puritanism, of later generations. -

Elisabeth Parr's Renaissance at the Mid-Tudor Court

Early Modern Women: An Interdisciplinary Journal 2013, vol. 8 Elisabeth Parr’s Renaissance at the Mid-Tudor Court Helen Graham-Matheson oan Kelly’s ground-breaking article, “Did Women Have a Renaissance?” Jcenters on four criteria for ascertaining the “relative contraction (or expansion) of the powers of Renaissance women”: women’s economic, political, cultural roles and the ideology about women across the mid- Tudor period. Focusing particularly on cultural and political roles, this essay applies Kelly’s criteria to Elisabeth Parr née Brooke, Marchioness of Northampton (1526–1565) and sister-in-law of Katherine Parr, Henry VIII’s last wife, whose controversial court career evinces women’s lived experience and their contemporary political importance across the mid- Tudor courts of Henry VIII, Edward VI, Mary I, and Elizabeth I. By taking each reign in isolation, this essay follows Kelly’s call to question “accepted schemes of periodization” and reassesses whether “events that further the historical development of men, liberating them from natural, social, or ideological constraints, have quite different, even opposite, effects upon women.”1 The key point of departure of my essay from Kelly’s argument is that she states that women’s involvement in the public sphere and politics lessened in the Italian cinquecento, whereas my findings suggest that in England women such as Elisabeth Parr increasingly involved themselves in the public world of court politics. According to Kelly, 1 Joan Kelly, ”Did Women Have a Renaissance?” Feminism and Renaissance Studies, ed. L. Hutson (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999), 21. 289 290 EMWJ 2013, vol. 8 Helen Graham-Matheson [n]oblewomen . -

Theatricality and Historiography in Shakespeare's Richard

H ISTRIONIC H ISTORY: Theatricality and Historiography in Shakespeare’s Richard III By David Hasberg Zirak-Schmidt This article focuses on Shakespeare’s history drama Richard III, and investigates the ambiguous intersections between early modern historiography and aesthetics expressed in the play’s use of theatrical and metatheatrical language. I examine how Shakespeare sought to address and question contemporary, ideologically charged representations of history with an analysis of the characters of Richard and Richmond, and the overarching theme of theatrical performance. By employing this strategy, it was possible for Shakespeare to represent the controversial character of Richard undogmatically while intervening in and questioning contemporary discussions of historical verisimilitude. Historians have long acknowledged the importance of the early modern history play in the development of popular historical consciousness.1 This is particularly true of England, where the history play achieved great commercial and artistic success throughout the 1590s. The Shakespearean history play has attracted by far the most attention from cultural and literary historians, and is often seen as the archetype of the genre. The tragedie of kinge RICHARD the THIRD with the death of the Duke of CLARENCE, or simply Richard III, is probably one of the most frequently performed of Shakespeare’s history plays. The play dramatizes the usurpation and short- lived reign of the infamous, hunchbacked Richard III – the last of the Plantagenet kings, who had ruled England since 1154 – his ultimate downfall, and the rise of Richmond, the future king Henry VII and founder of the Tudor dynasty. To the Elizabethan public, there was no monarch in recent history with such a dark reputation as Richard III: usurpation, tyranny, fratricide, and even incest were among his many alleged crimes, and a legacy of cunning dissimulation and cynical Machiavellianism had clung to him since his early biographers’ descriptions of him. -

The Reformation of the Generations: Age, Ancestry and Memory in England 1500-1700

The Reformation of the Generations: Age, Ancestry and Memory in England 1500-1700 Folger Shakespeare Library Spring Semester Seminar 2016 Alexandra Walsham (University of Cambridge): [email protected] The origins, impact and repercussions of the English Reformation have been the subject of lively debate. Although it is now widely recognised as a protracted process that extended over many decades and generations, surprisingly little attention has been paid to the links between the life cycle and religious change. Did age and ancestry matter during the English Reformation? To what extent did bonds of blood and kinship catalyse and complicate its path? And how did remembrance of these events evolve with the passage of the time and the succession of the generations? This seminar will investigate the connections between the histories of the family, the perception of the past, and England’s plural and fractious Reformations. It invites participants from a range of disciplinary backgrounds to explore how the religious revolutions and movements of the period shaped, and were shaped by, the horizontal relationships that early modern people formed with their sibilings, relatives and peers, as well as the vertical ones that tied them to their dead ancestors and future heirs. It will also consider the role of the Reformation in reconfiguring conceptions of memory, history and time itself. Schedule: The seminar will convene on Fridays 1-4.30pm, for 10 weeks from 5 February to 29 April 2016, excluding 18 March, 1 April and 15 April. In keeping with Folger tradition, there will be a tea break from 3.00 to 3.30pm. -

Prophecy in Shakespeare's English History Cycles Lee Joseph Rooney

Prophecy in Shakespeare’s English History Cycles Lee Joseph Rooney Thesis submitted in accordance with the requirements of the University of Liverpool for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy September 2014 Abstract Prophecy — that is, the action of foretelling or predicting the future, particularly a future thought to represent the will of God — is an ever-present aspect of Shakespeare’s historical dramaturgy. The purpose of this thesis is to offer a reading of the dramas of Shakespeare’s English history cycles — from 1 Henry VI to Henry V — that focuses exclusively upon the role played by prophecy in representing and reconstructing the past. It seeks to show how, through close attention to the moments when prophecy emerges in these historical dramas, we might arrive at a different understanding of them, both as dramatic narratives and as meditations on the nature of history itself. As this thesis seeks to demonstrate, moreover, Shakespeare’s treatment of prophecy in any one play can be viewed, in effect, as a key that can take us to the heart of that drama’s wider concerns. The comparatively recent conception of a body of historical plays that are individually distinct and no longer chained to the Tillyardian notion of a ‘Tudor myth’ (or any other ‘grand narrative’) has freed prophecy from effectively fulfilling the rather one-dimensional role of chorus. However, it has also raised as-yet- unanswered questions about the function of prophecy in Shakespeare’s English history cycles, which this thesis aims to consider. One of the key arguments presented here is that Shakespeare utilises prophecy not to emphasise the pervasiveness of divine truth and providential design, but to express the political, narratorial, and interpretative disorder of history itself. -

ABSTRACT REBECCA BRUYERE Mary Tudor and the Return

ABSTRACT REBECCA BRUYERE Mary Tudor and the Return of Catholicism (Under the direction of DR. BENJAMIN EHLERS) Ever since John Foxe's labeling of Mary as a bloody tyrant, the label has persisted throughout history even to the present day. Mary, however, was more in touch with her people than Foxe and others would portray her, as a more Catholic form of religion was widely supported. Many people began celebrating the Mass and other Catholic ceremonies even before Mary's ascent to the throne. Upon claiming the throne, Mary relied principally upon the support of the people to help her. She enacted a series of reforms against the more dramatically Protestant elements that her half-brother, King Edward VI, introduced. Most churches met the requirements for the reconstruction of their churches, a feat that was not easy during such difficult economic times. In doing so, the churches relied greatly upon the support of the parishioners, although Mary did try to ease the difficulty of building back Churches by returning various Catholic items. Through pamphlets, Mary and her bishops sought to educate England about Catholicism so that they might understand some of the more fundamental beliefs. Cardinal Pole was instrumental in assisting Mary as well, implementing reforms as well as preaching about Catholicism. However, a good many Protestants were burned as heretics. Despite Mary's intention for prudence, this was one of the low points of Mary's reign from a modern perspective. However, if Mary lived longer and had an heir, England probably would have had a more Catholic religion and would not have noted so strongly the burning of heretics. -

The Tragedy of King Richard the Third

Dating Shakespeare’s Plays: Richard III The Tragedy of King Richard t he Third with the Landing of Earle Richmond and the Battel at Boſworth Field he earliest date for The Tragedy of King murther of his innocent Nephewes: his Richard III (Q1) is 1577, the first edition tyrannicall vsurpation: with the whole of Holinshed. The latest possible date is at course of his detested life, and most deserued Tthe publication of the First Quarto in 1597. death. As it hath beene lately Acted by the Right honourable the Lord Chamber laine his seruants. By William Shake-speare. London Publication Date Printed by Thomas Creede, for Andrew Wise, dwelling in Paules Church yard, at the signe of the Angell. 1598. The Tragedy of King Richard III was registered in 1597, three years after The Contention( 2 Henry The play went through four more quartos before VI) and three years before The True Tragedy of the First Folio in 1623: Richard Duke of York (3 Henry VI): [Q3 1602] The Tragedie of King Richard [SR 1597] 20 Octobris. Andrewe Wise. Entred the third. Conteining his treacherous Plots for his copie vnder thandes of master Barlowe, against his brother Clarence: the pittifull and master warden Man. The tragedie of murther of his innocent Nephewes: his kinge Richard the Third with the death of the tyrannical vsurpation: with the whole course Duke of Clarence. of his detested life, and most deserued death. As it hath bene lately Acted by the Right The play was published anonymously: Honourable the Lord Cham berlaine his seruants. -

Richard III: Victim Or Villain?

Richard III: Victim or Villain? SYNOPSIS As a student in history class my favourite topic was always the Tudors and their monarchs. So, when presented with the opportunity to form an investigation into a historical period of my choice, without hesitation, I chose the Tudors. After researching, I settled on the controversies surrounding Richard III. Many of the contemporary records widely available are written by the Tudors, the family who usurped the English throne from Richard. I also looked into popular culture and the enduring image we see of Richard III in many dramas, due to Shakespeare. This led me to question how much of King Richard’s image was created by the Tudors and not necessarily based on historical fact. Hence, this led me to my question: “To what extent has the image of Richard III been shaped by Tudor historians?” The most prevalent depictions of Richard III are those that have been kept in popular history, most prominently, the Tudor depiction, through Shakespeare’s play Richard III. To answer my question, I focussed on assessing the role of the early Tudor historians, focussing on the work of Thomas More and Polydore Vergil, in creating the image of Richard III. I then looked at how this image was immortalised by Shakespeare in his historical tragedy Richard III. Finally, I considered more modern revisionists attempts, such as Philippa Langley and the team who led the 2012 dig to find Richard’s remains, and the impacts these efforts have had on revising King Richard III’s image. Jeremy Potter, through his work Good King Richard?1 was the main source which provided insight into the personal context of key historians Sir Thomas More and Polydore Vergil. -

The Purpose of This Thesis Is to Trace Lady Katherine Grey's Family from Princess Mary Tudor to Algernon Seymour a Threefold A

ABSTRACT THE FAMILY OF LADY KATHERINE GREY 1509-1750 by Nancy Louise Ferrand The purpose of this thesis is to trace Lady Katherine Grey‘s family from Princess Mary Tudor to Algernon Seymour and to discuss aspects of their relationship toward the hereditary descent of the English crown. A threefold approach was employed: an examination of their personalities and careers, an investigation of their relationship to the succession problem. and an attempt to draw those elements together and to evaluate their importance in regard to the succession of the crown. The State Papers. chronicles. diaries, and the foreign correspondence of ambassadors constituted the most important sources drawn upon in this study. The study revealed that. according to English tradition, no woman from the royal family could marry a foreign prince and expect her descendants to claim the crown. Henry VIII realized this point when he excluded his sister Margaret from his will, as she had married James IV of Scotland and the Earl of Angus. At the same time he designated that the children of his younger sister Mary Nancy Louise Ferrand should inherit the crown if he left no heirs. Thus, legally had there been strong sentiment expressed for any of Katherine Grey's sons or descendants, they, instead of the Stuarts. could possibly have become Kings of England upon the basis of Henry VIII's and Edward VI's wills. That they were English rather than Scotch also enhanced their claims. THE FAMILY OF LADY KATHERINE GREY 1509-1750 BY Nancy Louise Ferrand A THESIS Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department of History 1964 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am indebted to Dr. -

Love Thy Neighbor

Love Thy Neighbor An Exhibition Commemorating the Completion of the Episcopal Chapel of St. John the Divine Curated by Christopher D. Cook Urbana The Rare Book & Manuscript Library 2007 Designed and typeset by the curator in eleven-point Garamond Premier Pro using Adobe InDesign CS3 Published online and in print to accompany an exhibition held at The Rare Book & Manuscript Library, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 16 November 2007 through 12 January 2008 [Print version: ISBN 978-0-9788134-1-3] Copyright © 2007 by the Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois All rights reserved. Published 2007 Manufactured in the United States of America Contents Commendation, The Reverend Timothy J. Hallett 5 Introduction 7 A Brief History of the Book of Common Prayer, Thomas D. Kilton 9 Catalog of the Exhibition Beginnings 11 Embroidered Bindings 19 The Episcopal Church in the United States 21 On Church Buildings 24 Bibliography 27 [blank] Commendation It is perhaps a graceful accident that the Episcopal Chapel of St. John the Divine resides across the street from the University of Illinois Library’s remarkable collection of Anglicana. The Book of Common Prayer and the King James version of the Bible have been at the heart of Anglican liturgies for centuries. Both have also enriched the life and worship of millions of Christians beyond the Anglican Communion. This exhibition makes historic editions of these books accessible to a wide audience. Work on the Chapel has been undertaken not just for Anglicans and Episcopalians, but for the enrichment of the University and of the community, and will make our Church a more accessible resource to all comers. -

The Plantagenet in the Parish: the Burial of Richard III’S Daughter in Medieval London

The Plantagenet in the Parish: The Burial of Richard III’s Daughter in Medieval London CHRISTIAN STEER Westminster Abbey, the necropolis of royalty, is today a centre piece for commemoration. 1 It represents a line of kings, their consorts, children and cousins, their bodies and monuments flanked by those of loyal retainers and officials who had served the Crown. The medieval abbey contained the remains of Edward the Confessor through to Henry VII and was a mausoleum of monarchy. Studies have shown that this was not exclusive: members of the medieval royal family sometimes chose to be buried elsewhere, often in particular religious houses with which they were personally associated.2 Edward IV (d. 1483) was himself buried in his new foundation at St George’s Chapel, Windsor, where he was commemorated within his sumptuous chantry chapel.3 But the question of what became of their illegitimate issue has sometimes been less clear. One important royal bastard, Henry Fitz-Roy, Duke of Richmond and Somerset (d. 1536), the illegitimate son of Henry VIII, was buried appropriately with his in-laws, the Howard family in Thetford Priory.4 There is less certainty on the burials of other royal by-blows and the location of one such grave, of Lady Katherine Plantagenet, illegitimate daughter of Richard III, has hitherto remained unknown. This article seeks to correct this. Monuments in Medieval London Few monuments have survived in medieval London. Church rebuilding work during the middle ages, the removal of tombs and the stripping out of the religious houses during the Reformation, together with iconoclasm during the Civil War took their toll on London’s commemorative heritage. -

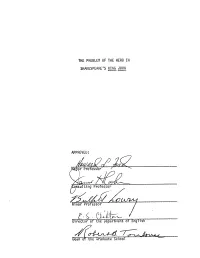

THE PROBLEM of the HERO in SHAKESPEARE's KING JOHN APPROVED: R Professor Suiting Professor Minor Professor Partment of English

THE PROBLEM OF THE HERO IN SHAKESPEARE'S KING JOHN APPROVED: r Professor / suiting Professor Minor Professor l-Q [Ifrector of partment of English Dean or the Graduate School THE PROBLEM OF THE HERO IN SHAKESPEARE'S KING JOHN THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Wilbert Harold Ratledge, Jr., B. A. Denton, Texas June, 1970 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. INTRODUCTION 1 II. THE MILIEU OF KING JOHN 7 III. TUDOR HISTORIOGRAPHY 12 IV. THE ENGLISH CHRONICLE PLAY 22 V. THE SOURCES OF KING JOHN 39 VI. JOHN AS HERO 54 VII. FAULCONBRIDGE AS HERO 67 VIII. ENGLAND AS HERO 82 IX. WHO IS THE VILLAIN? 102 X. CONCLUSION BIBLIOGRAPHY 118 in CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION During the last twenty-five years Shakespeare scholars have puolished at least five major works which deal extensively with Shakespeare's history plays. In addition, many critical articles concerning various aspects of the histories have been published. Some of this new material reinforces traditional interpretations of the history plays; some offers new avenues of approach and differs radically in its consideration of various elements in these dramas. King John is probably the most controversial of Shakespeare's history plays. Indeed, almost everything touching the play is in dis- pute. Anyone attempting to investigate this drama must be wary of losing his way among the labyrinths of critical argument. Critical opinion is amazingly divided even over the worth of King John. Hardin Craig calls it "a great historical play,"^ and John Masefield finds it to be "a truly noble play .