Richard III: Victim Or Villain?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cultural and Ideological Significance of Representations of Boudica During the Reigns of Elizabeth I and James I

EXETER UNIVERSITY AND UNIVERSITÉ D’ORLÉANS The Cultural and Ideological Significance Of Representations of Boudica During the reigns of Elizabeth I and James I. Submitted by Samantha FRENEE-HUTCHINS to the universities of Exeter and Orléans as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English, June 2009. This thesis is available for library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgment. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. ..................................... (signature) 2 Abstract in English: This study follows the trail of Boudica from her rediscovery in Classical texts by the humanist scholars of the fifteenth century to her didactic and nationalist representations by Italian, English, Welsh and Scottish historians such as Polydore Virgil, Hector Boece, Humphrey Llwyd, Raphael Holinshed, John Stow, William Camden, John Speed and Edmund Bolton. In the literary domain her story was appropriated under Elizabeth I and James I by poets and playwrights who included James Aske, Edmund Spenser, Ben Jonson, William Shakespeare, A. Gent and John Fletcher. As a political, religious and military figure in the middle of the first century AD this Celtic and regional queen of Norfolk is placed at the beginning of British history. In a gesture of revenge and despair she had united a great number of British tribes and opposed the Roman Empire in a tragic effort to obtain liberty for her family and her people. -

Theatricality and Historiography in Shakespeare's Richard

H ISTRIONIC H ISTORY: Theatricality and Historiography in Shakespeare’s Richard III By David Hasberg Zirak-Schmidt This article focuses on Shakespeare’s history drama Richard III, and investigates the ambiguous intersections between early modern historiography and aesthetics expressed in the play’s use of theatrical and metatheatrical language. I examine how Shakespeare sought to address and question contemporary, ideologically charged representations of history with an analysis of the characters of Richard and Richmond, and the overarching theme of theatrical performance. By employing this strategy, it was possible for Shakespeare to represent the controversial character of Richard undogmatically while intervening in and questioning contemporary discussions of historical verisimilitude. Historians have long acknowledged the importance of the early modern history play in the development of popular historical consciousness.1 This is particularly true of England, where the history play achieved great commercial and artistic success throughout the 1590s. The Shakespearean history play has attracted by far the most attention from cultural and literary historians, and is often seen as the archetype of the genre. The tragedie of kinge RICHARD the THIRD with the death of the Duke of CLARENCE, or simply Richard III, is probably one of the most frequently performed of Shakespeare’s history plays. The play dramatizes the usurpation and short- lived reign of the infamous, hunchbacked Richard III – the last of the Plantagenet kings, who had ruled England since 1154 – his ultimate downfall, and the rise of Richmond, the future king Henry VII and founder of the Tudor dynasty. To the Elizabethan public, there was no monarch in recent history with such a dark reputation as Richard III: usurpation, tyranny, fratricide, and even incest were among his many alleged crimes, and a legacy of cunning dissimulation and cynical Machiavellianism had clung to him since his early biographers’ descriptions of him. -

RHO Volume 35 Back Matter

WORKS OF THE CAMDEN SOCIETY AND ORDER OF THEIR PUBLICATION. 1. Restoration of King Edward IV. 2. Kyng Johan, by Bishop Bale For the year 3. Deposition of Richard II. >• 1838-9. 4. Plumpton Correspondence 6. Anecdotes and Traditions 6. Political Songs 7. Hayward's Annals of Elizabeth 8. Ecclesiastical Documents For 1839-40. 9. Norden's Description of Essex 10. Warkworth's Chronicle 11. Kemp's Nine Daies Wonder 12. The Egerton Papers 13. Chronica Jocelini de Brakelonda 14. Irish Narratives, 1641 and 1690 For 1840-41. 15. Rishanger's Chronicle 16. Poems of Walter Mapes 17. Travels of Nicander Nucius 18. Three Metrical Romances For 1841-42. 19. Diary of Dr. John Dee 20. Apology for the Lollards 21. Rutland Papers 22. Diary of Bishop Cartwright For 1842-43. 23. Letters of Eminent Literary Men 24. Proceedings against Dame Alice Kyteler 25. Promptorium Parvulorum: Tom. I. 26. Suppression of the Monasteries For 1843-44. 27. Leycester Correspondence 28. French Chronicle of London 29. Polydore Vergil 30. The Thornton Romances • For 1844-45. 31. Verney's Notes of the Long Parliament 32. Autobiography of Sir John Bramston • 33. Correspondence of James Duke of Perth I For 1845-46. 34. Liber de Antiquis Legibus 35. The Chronicle of Calais J Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.35.93, on 27 Sep 2021 at 13:24:50, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2042169900003692 CAMDEN K^AHkJ|f SOCIETY, FOR THE PUBLICATION OF EARLY HISTORICAL AND LITERARY REMAINS. -

Featuring Articles on Henry Wyatt, Elizabeth of York, and Edward IV Inside Cover

Richard III Society, Inc. Vol. 42 No. 3 September, 2011 Challenge in the Mist by Graham Turner Dawn on the 14th April 1471, Richard Duke of Gloucester and his men strain to pick out the Lancastrian army through the thick mist that envelopes the battlefield at Barnet. Printed with permission l Copyright © 2000 Featuring articles on Henry Wyatt, Elizabeth of York, and Edward IV Inside cover (not printed) Contents The Questionable Legend of Henry Wyatt.............................................................2 Elizabeth of York: A Biographical Saga................................................................8 Edward IV King of England 1461-83, the original type two diabetic?................14 Duchess of York—Cecily Neville: 1415-1495....................................................19 Errata....................................................................................................................24 Scattered Standards..............................................................................................24 Reviews................................................................................................................25 Behind the Scenes.................................................................................................32 A Few Words from the Editor..............................................................................37 Sales Catalog–September, 2011...........................................................................38 Board, Staff, and Chapter Contacts......................................................................43 -

Prophecy in Shakespeare's English History Cycles Lee Joseph Rooney

Prophecy in Shakespeare’s English History Cycles Lee Joseph Rooney Thesis submitted in accordance with the requirements of the University of Liverpool for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy September 2014 Abstract Prophecy — that is, the action of foretelling or predicting the future, particularly a future thought to represent the will of God — is an ever-present aspect of Shakespeare’s historical dramaturgy. The purpose of this thesis is to offer a reading of the dramas of Shakespeare’s English history cycles — from 1 Henry VI to Henry V — that focuses exclusively upon the role played by prophecy in representing and reconstructing the past. It seeks to show how, through close attention to the moments when prophecy emerges in these historical dramas, we might arrive at a different understanding of them, both as dramatic narratives and as meditations on the nature of history itself. As this thesis seeks to demonstrate, moreover, Shakespeare’s treatment of prophecy in any one play can be viewed, in effect, as a key that can take us to the heart of that drama’s wider concerns. The comparatively recent conception of a body of historical plays that are individually distinct and no longer chained to the Tillyardian notion of a ‘Tudor myth’ (or any other ‘grand narrative’) has freed prophecy from effectively fulfilling the rather one-dimensional role of chorus. However, it has also raised as-yet- unanswered questions about the function of prophecy in Shakespeare’s English history cycles, which this thesis aims to consider. One of the key arguments presented here is that Shakespeare utilises prophecy not to emphasise the pervasiveness of divine truth and providential design, but to express the political, narratorial, and interpretative disorder of history itself. -

George Ferrers and the Historian As Moral Compass.” LATCH 2 (2009): 101-114

Charles Beem. “From Lydgate to Shakespeare: George Ferrers and the Historian as Moral Compass.” LATCH 2 (2009): 101-114. From Lydgate to Shakespeare: George Ferrers and the Historian as Moral Compass Charles Beem University of North Carolina, Pembroke Essay In or around the year 1595, playwright William Shakespeare wrote the historical tragedy Richard II, the chronological starting point for a series of historical plays that culminates with another, better known historical tragedy Richard III. The historical sources Shakespeare consulted to fashion the character of Richard II and a procession of English kings from Henry IV to Richard III included the chronicles of Edward Hall and Raphael Holinshed, as well as the immensely popular The Mirror For Magistrates, which covered the exact same chronological range of Shakespeare’s Ricardian and Henrician historical plays. While Hall’s and Holinshed’s works were mostly straightforward prose narratives, The Mirror was a collaborative poetic history, which enjoyed several print editions over the course of Elizabeth I’s reign. Subjects in The Mirror appear as ghosts to tell their woeful tales of how they rose so high only to fall so hard, a device frequently employed in a number of Shakespeare’s plays, including Richard III. Among the various contributors to The Mirror for Magistrates was a gentleman by the name of George Ferrers. While it is highly unlikely that Shakespeare and Ferrers ever met—indeed, Shakespeare was only 15 when Ferrers died in 1579 at the ripe old age of 69. It is much more certain that Shakespeare was acquainted with Ferrers’ literary works. -

The Tragedy of King Richard the Third

Dating Shakespeare’s Plays: Richard III The Tragedy of King Richard t he Third with the Landing of Earle Richmond and the Battel at Boſworth Field he earliest date for The Tragedy of King murther of his innocent Nephewes: his Richard III (Q1) is 1577, the first edition tyrannicall vsurpation: with the whole of Holinshed. The latest possible date is at course of his detested life, and most deserued Tthe publication of the First Quarto in 1597. death. As it hath beene lately Acted by the Right honourable the Lord Chamber laine his seruants. By William Shake-speare. London Publication Date Printed by Thomas Creede, for Andrew Wise, dwelling in Paules Church yard, at the signe of the Angell. 1598. The Tragedy of King Richard III was registered in 1597, three years after The Contention( 2 Henry The play went through four more quartos before VI) and three years before The True Tragedy of the First Folio in 1623: Richard Duke of York (3 Henry VI): [Q3 1602] The Tragedie of King Richard [SR 1597] 20 Octobris. Andrewe Wise. Entred the third. Conteining his treacherous Plots for his copie vnder thandes of master Barlowe, against his brother Clarence: the pittifull and master warden Man. The tragedie of murther of his innocent Nephewes: his kinge Richard the Third with the death of the tyrannical vsurpation: with the whole course Duke of Clarence. of his detested life, and most deserued death. As it hath bene lately Acted by the Right The play was published anonymously: Honourable the Lord Cham berlaine his seruants. -

Love Thy Neighbor

Love Thy Neighbor An Exhibition Commemorating the Completion of the Episcopal Chapel of St. John the Divine Curated by Christopher D. Cook Urbana The Rare Book & Manuscript Library 2007 Designed and typeset by the curator in eleven-point Garamond Premier Pro using Adobe InDesign CS3 Published online and in print to accompany an exhibition held at The Rare Book & Manuscript Library, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 16 November 2007 through 12 January 2008 [Print version: ISBN 978-0-9788134-1-3] Copyright © 2007 by the Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois All rights reserved. Published 2007 Manufactured in the United States of America Contents Commendation, The Reverend Timothy J. Hallett 5 Introduction 7 A Brief History of the Book of Common Prayer, Thomas D. Kilton 9 Catalog of the Exhibition Beginnings 11 Embroidered Bindings 19 The Episcopal Church in the United States 21 On Church Buildings 24 Bibliography 27 [blank] Commendation It is perhaps a graceful accident that the Episcopal Chapel of St. John the Divine resides across the street from the University of Illinois Library’s remarkable collection of Anglicana. The Book of Common Prayer and the King James version of the Bible have been at the heart of Anglican liturgies for centuries. Both have also enriched the life and worship of millions of Christians beyond the Anglican Communion. This exhibition makes historic editions of these books accessible to a wide audience. Work on the Chapel has been undertaken not just for Anglicans and Episcopalians, but for the enrichment of the University and of the community, and will make our Church a more accessible resource to all comers. -

John Miltonâ•Žs History of Britain: Its Place in English Historiography

Studies in English Volume 6 Article 9 1965 John Milton’s History of Britain: Its Place in English Historiography Michael Landon University of Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/ms_studies_eng Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Landon, Michael (1965) "John Milton’s History of Britain: Its Place in English Historiography," Studies in English: Vol. 6 , Article 9. Available at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/ms_studies_eng/vol6/iss1/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in English by an authorized editor of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Landon: John Milton’s History of Britain: Its Place in English Historiogr JOHN MILTON'S HISTORY OF BRITAIN ITS PLACE IN ENGLISH HISTORIOGRAPHY by Michael Landon The History of Britain, that part especially now called England, from the first traditional Beginning continued to the Norman Conquest, by John Milton, was written at intervals between 1646 and 1660 and was first published in 1670 by James Allestry in a quarto volume of some three hundred and fifty pages which sold for five shillings.1 Few think of Milton as a historian, although anyone familiar with Paradise Lost alone of his best known works will realize that the famous mid-seventeenth century poet knew and had a pro found sense of history.2* His History of Britain has tended to be neglected by Milton scholars and has not as yet been critically -

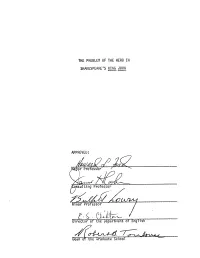

THE PROBLEM of the HERO in SHAKESPEARE's KING JOHN APPROVED: R Professor Suiting Professor Minor Professor Partment of English

THE PROBLEM OF THE HERO IN SHAKESPEARE'S KING JOHN APPROVED: r Professor / suiting Professor Minor Professor l-Q [Ifrector of partment of English Dean or the Graduate School THE PROBLEM OF THE HERO IN SHAKESPEARE'S KING JOHN THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Wilbert Harold Ratledge, Jr., B. A. Denton, Texas June, 1970 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. INTRODUCTION 1 II. THE MILIEU OF KING JOHN 7 III. TUDOR HISTORIOGRAPHY 12 IV. THE ENGLISH CHRONICLE PLAY 22 V. THE SOURCES OF KING JOHN 39 VI. JOHN AS HERO 54 VII. FAULCONBRIDGE AS HERO 67 VIII. ENGLAND AS HERO 82 IX. WHO IS THE VILLAIN? 102 X. CONCLUSION BIBLIOGRAPHY 118 in CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION During the last twenty-five years Shakespeare scholars have puolished at least five major works which deal extensively with Shakespeare's history plays. In addition, many critical articles concerning various aspects of the histories have been published. Some of this new material reinforces traditional interpretations of the history plays; some offers new avenues of approach and differs radically in its consideration of various elements in these dramas. King John is probably the most controversial of Shakespeare's history plays. Indeed, almost everything touching the play is in dis- pute. Anyone attempting to investigate this drama must be wary of losing his way among the labyrinths of critical argument. Critical opinion is amazingly divided even over the worth of King John. Hardin Craig calls it "a great historical play,"^ and John Masefield finds it to be "a truly noble play . -

The Causes of Tyranny As a Guide to Political Reform: St

THE CAUSES OF TYRANNY AS A GUIDE TO POLITICAL REFORM: ST. THOMAS MORE’S HISTORY OF KING RICHARD III OF ENGLAND Carle Mock, Ph.D. University of Dallas, 2017 Dr. Gerard Wegemer, Director Part One of this dissertation establishes a basis for interpreting More’s History of King Richard III. Chapter One inquires into its genre, concluding it is a “rhetorical history” like the histories composed by Thucydides, Livy, Sallust, and Tacitus, a genre similar to drama which aims to reveal fundamental moral and political truths by following classical rhetorical principles. Chapter Two investigates the relationship between the nine textually significant extant versions of this work, and concludes that they derive from a series of revised drafts. The English versions are shown to be preliminary drafts, with the Paris manuscript being the Latin version based on the latest draft. Chapter Three analyzes the changes between drafts and finds that More carefully revised his work and paid particular attention to concepts important in political philosophy. The four chapters of Part Two interpret the work's political teaching. Chapter Four introduces the major theme—the causes of tyranny in the England depicted—by contrasting tyranny with a good political order, “republic.” This chapter defines tyranny, distinguishes the tyrant Richard from the merely bad king Edward, notes the relationship between tyranny and faction, and describes the attributes of a republic and its members, “citizens.” It also discusses aligning public and private interests and avoiding conflicts of interest as principles of political reform. Chapter Five inquires into institutional causes of tyranny, discussing sanctuary and the dangers of imprudent rational critique, the strengths and weaknesses of England's criminal, civil, and constitutional law, and the weaknesses of hereditary kingship. -

Lambert Simnel and the King from Dublin

Lambert Simnel and the King from Dublin GORDON SMITH Throughout his reign (1485-1509) Richard III's supplanter Henry VII was troubled by pretenders to his throne, the most important of whom were Lambert Simnel and Perkin Warbeck.1 Both are popularly remembered perhaps because their names have a pantomime sound to them, and a pantomime context seems a suitable one for characters whom Henry accused of being not real pretenders but mere impersonators. Nevertheless, there have been some doubts about the imposture of Perkin, although there appear to have been none before now about Lambert.2 As A.F. Pollard observed, 'no serious historian has doubted that Lambert was an impostor'.3 This observation is supported by the seemingly straightforward traditional story about the impostor Lambert Simnel, who was crowned king in Dublin but defeated at the battle of Stoke in 1487, and pardoned by Henry VII. This story can be recognised in Francis Bacon's influential history of Henry's reign, published in 1622, where Lambert first impersonated Richard, Duke of York, the younger son of Edward IV, before changing his imposture to Edward, Earl of Warwick.4 Bacon and the sixteenth century historians derived their account of the 1487 insurrection mainly from Polydore Vergil's Anglica Historia, but Vergil, in his manuscript compiled between 1503 and 1513, said only that Simnel counterfeited Warwick.5 The impersonation of York derived from a life of Henry VII, written around 1500 by Bernard André, who failed to name Lambert.6 Bacon's York-Warwick imitation therefore looks like a conflation of the impostures from André and Vergil.