Sir Alan Cottrell Interviewed by Tom Lean

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Renaissance Society of America Annual Meeting

CHICAGO 30 March–1 April 2017 RSA 2017 Annual Meeting, Chicago, 30 March–1 April Photograph © 2017 The Art Institute of Chicago. Institute The Art © 2017 Photograph of Chicago. Institute The Art © 2017 Photograph The Renaissance Society of America Annual Meeting The Renaissance Society of America Annual Meeting Program Chicago 30 March–1 April 2017 Front and back covers: Jacob Halder and Workshop, English, Greenwich, active 1576–1608. Portions of a Field Armor, ca. 1590. Steel, etched and gilded, iron, brass, and leather. George F. Harding Collection, 1982.2241a-h. Art Institute of Chicago. Contents RSA Executive Board .......................................................................5 RSA Staff ........................................................................................6 RSA Donors in 2016 .......................................................................7 RSA Life Members ...........................................................................8 RSA Patron Members....................................................................... 9 Sponsors ........................................................................................ 10 Program Committee .......................................................................10 Discipline Representatives, 2015–17 ...............................................10 Participating Associate Organizations ............................................. 11 Registration and Book Exhibition ...................................................14 Policy on Recording and Live -

Vancouver Institute: an Experiment in Public Education

1 2 The Vancouver Institute: An Experiment in Public Education edited by Peter N. Nemetz JBA Press University of British Columbia Vancouver, B.C. Canada V6T 1Z2 1998 3 To my parents, Bel Newman Nemetz, B.A., L.L.D., 1915-1991 (Pro- gram Chairman, The Vancouver Institute, 1973-1990) and Nathan T. Nemetz, C.C., O.B.C., Q.C., B.A., L.L.D., 1913-1997 (President, The Vancouver Institute, 1960-61), lifelong adherents to Albert Einstein’s Credo: “The striving after knowledge for its own sake, the love of justice verging on fanaticism, and the quest for personal in- dependence ...”. 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION: 9 Peter N. Nemetz The Vancouver Institute: An Experiment in Public Education 1. Professor Carol Shields, O.C., Writer, Winnipeg 36 MAKING WORDS / FINDING STORIES 2. Professor Stanley Coren, Department of Psychology, UBC 54 DOGS AND PEOPLE: THE HISTORY AND PSYCHOLOGY OF A RELATIONSHIP 3. Professor Wayson Choy, Author and Novelist, Toronto 92 THE IMPORTANCE OF STORY: THE HUNGER FOR PERSONAL NARRATIVE 4. Professor Heribert Adam, Department of Sociology and 108 Anthropology, Simon Fraser University CONTRADICTIONS OF LIBERATION: TRUTH, JUSTICE AND RECONCILIATION IN SOUTH AFRICA 5. Professor Harry Arthurs, O.C., Faculty of Law, Osgoode 132 Hall, York University GLOBALIZATION AND ITS DISCONTENTS 6. Professor David Kennedy, Department of History, 154 Stanford University IMMIGRATION: WHAT THE U.S. CAN LEARN FROM CANADA 7. Professor Larry Cuban, School of Education, Stanford 172 University WHAT ARE GOOD SCHOOLS, AND WHY ARE THEY SO HARD TO GET? 5 8. Mr. William Thorsell, Editor-in-Chief, The Globe and 192 Mail GOOD NEWS, BAD NEWS: POWER IN CANADIAN MEDIA AND POLITICS 9. -

Sir Alan Cottrell Receives Von Hippel Award

MRS NEWS Sir Alan Cottrell Receives Von Hippel Award The Materials Research Society's highest dislocation theory and the electron theory honor, the Von Hippel Award, this year of metals and alloys. His books have been will be given to Sir Alan Cottrell, honor- profoundly influential in educating genera- - able distinguished research fellow in the tions of diverse materials scientists. Some of Department of Materials Science and his papers have established links to inor- Metallurgy, Cambridge University. He ganic chemistry, especially his active inter- was cited for "converting crystal disloca- est in what constitutes a metal and in the tions from a handwaving hypothesis to a metal-insulator transition. rigorous discipline, transforming the Sir Alan Cottrell is one of the most hon- understanding of brittle fracture, making ored materials scientists. He was knighted varied and crucial advances in the theory by Queen Elizabeth in 1971, and is a fel- of radiation damage, and for transforming low of both the Royal Society and the the teaching of materials science through- Royal Academy of Engineering. He has out the academic world through his pio- received 16 honorary degrees and an even neering textbooks." The Von Hippel greater number of medals and awards Award is given annually to an individual from professional societies and other in recognition of outstanding contributions organizations around the world. He has to interdisciplinary research on materials. written 11 books, including several clas- Sir Alan's earliest research was in solidly of the whole country." His expertise on sics, and more than 160 scientific papers. practical metallurgy related to welding, the fracture mechanics of reactor pressure Sir Alan received his BSc degree in 1939 work hardening, and precipitation harden- vessels, linked to his knowledge of radia- from the University of Birmingham, fol- ing, areas where he always displayed a fine tion embrittlement, has been valuable to lowed by a PhD degree in 1942. -

A Field Dislocation Mechanics Approach to Emergent Properties in Two-Phase Nickel-Based Superalloys

A Field Dislocation Mechanics Approach To Emergent Properties In Two-Phase Nickel-Based Superalloys By James Jordan Little A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF ENGINEERING School of Metallurgy and Materials College of Engineering and Physical Sciences University of Birmingham March 2019 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract The objective of this study is the development of a theoretical framework for treating the flow stress response of two-phase alloys as emergent behaviour arising from fundamental dislocation interactions. To this end a field dislocation mechanics (FDM) formulation has been developed to model heterogeneous slip within a computational domain representative of a two-phase nickel- based superalloy crystal at elevated temperature. A transport equation for the statistically stored dislocation (SSD) field is presented and implemented within a plane strain finite element scheme. Elastic interactions between dislocations and the microstructure are explicitly accounted for in this formulation. The theory has been supplemented with constitutive rules for dislocation glide and climb, as well as local cutting conditions for the γ0 particles by the dislocation field. -

Download Chapter 66KB

Memorial Tributes: Volume 20 Copyright National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. Memorial Tributes: Volume 20 ANTHONY KELLY 1929–2014 Elected in 1986 “For pioneering research in the development of strong solids and composite materials.” BY ARCHIE HOWIE SUBMITTED BY THE NAE HOME SECRETARY ANTHONY KELLY, a seminal figure in the development of composite materials and a reforming vice chancellor at the Uni- versity of Surrey, died on June 3, 2014, at the age of 85. Tony, as he was generally known, was born in Hillingdon, West London, on January 25, 1929. His father, Group Captain Vincent Gerald French Kelly, who was of Irish descent, taught mathematics to pilots in the education service of the Royal Air Force. Tony’s scientific promise became apparent at the age of 13 in Presentation College, Reading, when he successfully corrected a physics teacher’s work on the blackboard. Since Presentation College did not have a sixth form, he had to develop his own habit for intensive study and teach himself enough physics, chemistry, geography, and geology to take the University Intermediate Examination and win an open scholarship in science at the University of Reading. Tony’s doctoral research was carried out between 1950 and 1953 at the Cavendish Laboratory, Cambridge, in Sir Lawrence Bragg’s famous crystallography group. Although his formal supervisor was W.H. Taylor and he had intermittent guid- ance from Bragg, his main mentor was Peter Hirsch, who had been largely responsible for setting up the x-ray microbeam equipment and exploring its use to investigate the structure of deformed metals. -

{PDF} Charles Darwin, the Copley Medal, and the Rise of Naturalism

CHARLES DARWIN, THE COPLEY MEDAL, AND THE RISE OF NATURALISM 1862-1864 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Marsha Driscoll | 9780205723171 | | | | | Charles Darwin, the Copley Medal, and the Rise of Naturalism 1862-1864 1st edition PDF Book In recognition of his distinguished work in the development of the quantum theory of atomic structure. In recognition of his distinguished studies of tissue transplantation and immunological tolerance. Dunn, Dann Siems, and B. Alessandro Volta. Tomas Lindahl. Thomas Henry Huxley. Andrew Huxley. Adam Sedgwick. Ways and Means, Science and Society Picture Library. John Smeaton. Each year the award alternates between the physical and biological sciences. On account of his curious Experiments and Discoveries concerning the different refrangibility of the Rays of Light, communicated to the Society. David Keilin. For his seminal work on embryonic stem cells in mice, which revolutionised the field of genetics. Derek Barton. This game is set in and involves debates within the Royal Society on whether Darwin should receive the Copley Medal, the equivalent of the Nobel Prize in its day. Frank Fenner. For his Paper communicated this present year, containing his Experiments relating to Fixed Air. Read and download Log in through your school or library. In recognition of his pioneering work on the structure of muscle and on the molecular mechanisms of muscle contraction, providing solutions to one of the great problems in physiology. James Cook. Wilhelm Eduard Weber. For his investigations on the morphology and histology of vertebrate and invertebrate animals, and for his services to biological science in general during many past years. Retrieved John Ellis. -

Sir Alan Howard Cottrell Scd, FRS, Freng, LLD (Hon) (17 July 1919 – 15 February 2012)

Sir Alan Howard Cottrell ScD, FRS, FREng, LLD (Hon) (17 July 1919 – 15 February 2012) With the death of Sir Alan we have lost a scientific ‘Colossus’ in the field of materials science and metallurgy. Entering Birmingham University from Moseley Grammar School to read Metallurgy, Alan graduated in 1939 and obtained a PhD in 1942 for research in the field of steel welding, of significance in relation to tank armour. He was greatly influenced by the Head of Department, Professor David Hanson. Recognising Cottrell’s outstanding scientific ability, Hanson took him onto his staff with the remit of developing modern science concepts in both the teaching and research in the Birmingham Department, aided by Raynor from Oxford where the atomic theory of metals was being developed by Hume Rothery. Cottrell had then to teach himself the level of advanced physics unknown to a conventional metallurgist, which was necessary for the task that he had been set. This enabled him in his own research to take dislocation theory forward, to make it more quantitative, and to explain, for example, the phenomenon of the yield point and strain ageing in steel. At the early age of 30 he was appointed Professor of Physical Metallurgy, always showing an ability to present difficult subjects in a new and understandable way. Recognising a rising star, he was made Deputy Head of the Metallurgy Division at the AERE Harwell Laboratory in 1955 where it was becoming clear that a structural atomistic approach was necessary to understand and predict the behaviour of materials in modern reactors. In January 1958 he was approached by Lord Adrian, Vice Chancellor of Cambridge University, to take the Goldsmiths’ Chair of Metallurgy, vacant following the retirement of G P Wesley Austin. -

Download Chapter 189KB

Memorial Tributes: Volume 22 Copyright National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. Memorial Tributes: Volume 22 WALTER C. MARSHALL 1932–1996 Elected in 1979 “Contributions to the technology and direction of nuclear energy programs and to the transfer of the technology to industry.” BY DAVID FISHLOCK AND L.E.J. ROBERTS SUBMITTED BY THE NAE HOME SECRETARY WALTER CHARLES MARSHALL died February 20, 1996, at age 63 in London. He was recognized by the scientific commu- nity at an early age as one of the outstanding theoretical physi- cists of his generation. But he is more likely to be remembered for his distinguished career in public service, which led to a knighthood in 1981 and a life peerage in 1985, and for his forth- right public advocacy of nuclear power. Early Years: Pure and Then Applied Scientist Walter Marshall was born March 5, 1932, in Rumney, near Cardiff, the youngest child of three. In later years, he delighted to recall that he had insisted on “doing sums” on his first day in primary school. His mathematical promise was recognized by his mathematics teacher, Mr. Wustenholme, in grammar school, St. Illtyd’s College in Cardiff. He also developed a seri- ous interest in chess at the age of 11 and became the Welsh Junior Chess Champion at 15. He left school with a major county scholarship in 1949 to study mathematical physics at the University of Birmingham, Adapted and reprinted with the permission of the Royal Society. Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society 44:299–312, published November 1, 1998. -

Harnessing Stochasticity Collection

The Harnessing of Stochasticity Physiological and philosophical consequences Articles by Raymond and Denis Noble This pdf collection of 9 articles brings together a developing story. It can be seen as the culmination of many years of discussions between the two of us on the nature of biology, what causes what and how, and what evolves and how. Those discussions long predate the first articles to appear. The opening shot in print was the 2012 formulation in Interface Focus of the mathematical basis of the principle of biological relativity, meaning relativity of causation by different levels of organisation ganisms in or , which had already been implied in The Music of Life (2006). That principle is insufficient on its own since there has also to be a specific process by which lower level processes are constrained by higher-‐level organisation. The beginnings of identifying that process as including the harnessing of stochasticity occurred at the 2016 meeting at The Royal Society on New Trends in Evolutionary Biology, published in Interface Focus in 2017. But that idea was not followed up in the Discussion Meeting itself, very except for a helpful chance meeting we had with the immunologist Richard Moxon during breakfast the next day. What really set discussion alight was the 2017 article in Biology, which was the subject of a very lengthy interaction -‐ with a neo darwinist referee. That was followed by a cascade of invitations the for subsequent articles published in a variety of journals leading up to the Journal 2020 article in the for the General Philosophy of Science. -

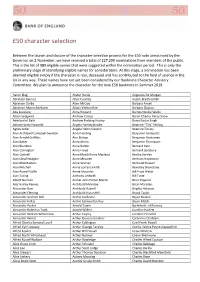

50 Character Selection

£50 character selection Between the launch and closure of the character selection process for the £50 note announced by the Governor on 2 November, we have received a total of 227,299 nominations from members of the public. This is the list of 989 eligible names that were suggested within the nomination period. This is only the preliminary stage of identifying eligible names for consideration: At this stage, a nomination has been deemed eligible simply if the character is real, deceased and has contributed to the field of science in the UK in any way. These names have not yet been considered by our Banknote Character Advisory Committee. We plan to announce the character for the new £50 banknote in Summer 2019. Aaron Klug Alister Hardy Augustus De Morgan Abraham Bennet Allen Coombs Austin Bradford Hill Abraham Darby Allen McClay Barbara Ansell Abraham Manie Adelstein Alliott Verdon Roe Barbara Clayton Ada Lovelace Alma Howard Barnes Neville Wallis Adam Sedgwick Andrew Crosse Baron Charles Percy Snow Aderlard of Bath Andrew Fielding Huxley Bawa Kartar Singh Adrian Hardy Haworth Angela Hartley Brodie Beatrice "Tilly" Shilling Agnes Arber Angela Helen Clayton Beatrice Tinsley Alan Archibald Campbell‐Swinton Anita Harding Benjamin Gompertz Alan Arnold Griffiths Ann Bishop Benjamin Huntsman Alan Baker Anna Atkins Benjamin Thompson Alan Blumlein Anna Bidder Bernard Katz Alan Carrington Anna Freud Bernard Spilsbury Alan Cottrell Anna MacGillivray Macleod Bertha Swirles Alan Lloyd Hodgkin Anne McLaren Bertram Hopkinson Alan MacMasters Anne Warner -

Fred Hoyle's Universe

FRED HOYLE’S UNIVERSE This page intentionally left blank FRED HOYLE’S UNIVERSE Jane Gregory 1 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford ox2 6dp Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York © Jane Gregory 2005 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2005 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organizations. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Data available ISBN 0–19–850791–7 13579108642 Typeset by RefineCatch Limited, Bungay, Suffolk Printed in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, St Ives plc Contents Acknowledgements ix 1 Coming to light 1 Schooldays and scientific ambition; undergraduate life at Cambridge; becoming a mathematician; graduate studies; marriage to Barbara 2 Hut no. -

Conference on Manuscript Studies 1974-2017

SAINT LOUIS CONFERENCE ON MANUSCRIPT STUDIES PROGRAMS 1974–2017 From 1974 to 2017 the Saint Louis Conference on Manuscript Studies—which features papers on medieval and Renaissance manuscript studies, including such topics as paleography, codicology, illumination, text editing, library history, cataloguing, etc.—was organized and hosted by the Vatican Film Library at Saint Louis University. The conference continues and is now held under the auspices of the Saint Louis University Center for Medieval & Renaissance Studies as part of its Annual Symposium on Medieval and Renaissance Studies. 44th Conference (2017) pp. 3–14 43rd Conference (2016) pp. 15–26 42nd Conference (2015) pp. 27–38 41st Conference (2014) pp. 39–49 40th Conference (2013) pp. 50–60 39th Conference (2012) pp. 61–72 38th Conference (2011) pp. 73–84 37th Conference (2010) pp. 85–95 36th Conference (2009) pp. 96–107 35th Conference (2008) pp. 108–111 34th Conference (2007) pp. 112–115 33rd Conference (2006) pp. 116–119 32nd Conference (2005) pp. 120–123 31st Conference (2004) pp. 124–127 30th Conference (2003) pp. 128–130 29th Conference (2002) pp. 131–133 28th Conference (2001) pp. 134–137 27th Conference (2000) pp. 138–140 26th Conference (1999) pp. 141–143 25th Conference (1998) pp. 144–147 24th Conference (1997) pp. 148–151 23rd Conference (1996) pp. 152–155 22nd Conference (1995) pp. 156–159 21st Conference (1994) pp. 160–164 20th Conference (1993) pp. 165–167 19th Conference (1992) pp. 168–170 18th Conference (1991) pp. 171–174 17th Conference (1990) pp. 175–178 16th Conference (1989) pp. 179–182 15th Conference (1988) pp.