Defining and Sizing-Up Mountains

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Los Cien Montes Más Prominentes Del Planeta D

LOS CIEN MONTES MÁS PROMINENTES DEL PLANETA D. Metzler, E. Jurgalski, J. de Ferranti, A. Maizlish Nº Nombre Alt. Prom. Situación Lat. Long. Collado de referencia Alt. Lat. Long. 1 MOUNT EVEREST 8848 8848 Nepal/Tibet (China) 27°59'18" 86°55'27" 0 2 ACONCAGUA 6962 6962 Argentina -32°39'12" -70°00'39" 0 3 DENALI / MOUNT McKINLEY 6194 6144 Alaska (USA) 63°04'12" -151°00'15" SSW of Rivas (Nicaragua) 50 11°23'03" -85°51'11" 4 KILIMANJARO (KIBO) 5895 5885 Tanzania -3°04'33" 37°21'06" near Suez Canal 10 30°33'21" 32°07'04" 5 COLON/BOLIVAR * 5775 5584 Colombia 10°50'21" -73°41'09" local 191 10°43'51" -72°57'37" 6 MOUNT LOGAN 5959 5250 Yukon (Canada) 60°34'00" -140°24’14“ Mentasta Pass 709 62°55'19" -143°40’08“ 7 PICO DE ORIZABA / CITLALTÉPETL 5636 4922 Mexico 19°01'48" -97°16'15" Champagne Pass 714 60°47'26" -136°25'15" 8 VINSON MASSIF 4892 4892 Antarctica -78°31’32“ -85°37’02“ 0 New Guinea (Indonesia, Irian 9 PUNCAK JAYA / CARSTENSZ PYRAMID 4884 4884 -4°03'48" 137°11'09" 0 Jaya) 10 EL'BRUS 5642 4741 Russia 43°21'12" 42°26'21" West Pakistan 901 26°33'39" 63°39'17" 11 MONT BLANC 4808 4695 France 45°49'57" 06°51'52" near Ozero Kubenskoye 113 60°42'12" c.37°07'46" 12 DAMAVAND 5610 4667 Iran 35°57'18" 52°06'36" South of Kaukasus 943 42°01'27" 43°29'54" 13 KLYUCHEVSKAYA 4750 4649 Kamchatka (Russia) 56°03'15" 160°38'27" 101 60°23'27" 163°53'09" 14 NANGA PARBAT 8125 4608 Pakistan 35°14'21" 74°35'27" Zoji La 3517 34°16'39" 75°28'16" 15 MAUNA KEA 4205 4205 Hawaii (USA) 19°49'14" -155°28’05“ 0 16 JENGISH CHOKUSU 7435 4144 Kyrghysztan/China 42°02'15" 80°07'30" -

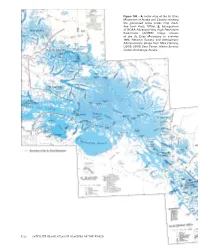

Alaska Range

Alaska Range Introduction The heavily glacierized Alaska Range consists of a number of adjacent and discrete mountain ranges that extend in an arc more than 750 km long (figs. 1, 381). From east to west, named ranges include the Nutzotin, Mentas- ta, Amphitheater, Clearwater, Tokosha, Kichatna, Teocalli, Tordrillo, Terra Cotta, and Revelation Mountains. This arcuate mountain massif spans the area from the White River, just east of the Canadian Border, to Merrill Pass on the western side of Cook Inlet southwest of Anchorage. Many of the indi- Figure 381.—Index map of vidual ranges support glaciers. The total glacier area of the Alaska Range is the Alaska Range showing 2 approximately 13,900 km (Post and Meier, 1980, p. 45). Its several thousand the glacierized areas. Index glaciers range in size from tiny unnamed cirque glaciers with areas of less map modified from Field than 1 km2 to very large valley glaciers with lengths up to 76 km (Denton (1975a). Figure 382.—Enlargement of NOAA Advanced Very High Resolution Radiometer (AVHRR) image mosaic of the Alaska Range in summer 1995. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration image mosaic from Mike Fleming, Alaska Science Center, U.S. Geological Survey, Anchorage, Alaska. The numbers 1–5 indicate the seg- ments of the Alaska Range discussed in the text. K406 SATELLITE IMAGE ATLAS OF GLACIERS OF THE WORLD and Field, 1975a, p. 575) and areas of greater than 500 km2. Alaska Range glaciers extend in elevation from above 6,000 m, near the summit of Mount McKinley, to slightly more than 100 m above sea level at Capps and Triumvi- rate Glaciers in the southwestern part of the range. -

Chapter Four

Chapter Four South Denali Visitor Center Complex: Interpretive Master Plan Site Resources Tangible Natural Site Features 1. Granite outcroppings and erratic Resources are at the core of an boulders (glacial striations) interpretive experience. Tangible resources, those things that can be seen 2. Panoramic views of surrounding or touched, are important for connecting landscape visitors physically to a unique site. • Peaks of the Alaska Range Intangible resources, such as concepts, (include Denali/Mt. McKinley, values, and events, facilitate emotional Mt. Foraker, Mt. Hunter, Mt. and meaningful experiences for visitors. Huntington, Mt. Dickey, Moose’s Effective interpretation occurs when Erratic boulders on Curry Ridge. September, 2007 Tooth, Broken Tooth, Tokosha tangible resources are connected with Mountains) intangible meanings. • Peters Hills • Talkeetna Mountains The visitor center site on Curry Ridge maximizes access to resources that serve • Braided Chulitna River and valley as tangible connections to the natural and • Ruth Glacier cultural history of the region. • Curry Ridge The stunning views from the visitor center site reveal a plethora of tangible Mt. McKinley/Denali features that can be interpreted. This Mt. Foraker Mt. Hunter Moose’s Tooth shot from Google Earth shows some of the major ones. Tokosha Ruth Glacier Mountains Chulitna River Parks Highway Page 22 3. Diversity of habitats and uniquely 5. Unfettered views of the open sky adapted vegetation • Aurora Borealis/Northern Lights • Lake 1787 (alpine lake) • Storms, clouds, and other weather • Alpine Tundra (specially adapted patterns plants, stunted trees) • Sun halos and sun dogs • High Brush (scrub/shrub) • Spruce Forests • Numerous beaver ponds and streams Tangible Cultural Site Features • Sedge meadows and muskegs 1. -

North American Notes

268 NORTH AMERICAN NOTES NORTH AMERICAN NOTES BY KENNETH A. HENDERSON HE year I 967 marked the Centennial celebration of the purchase of Alaska from Russia by the United States and the Centenary of the Articles of Confederation which formed the Canadian provinces into the Dominion of Canada. Thus both Alaska and Canada were in a mood to celebrate, and a part of this celebration was expressed · in an extremely active climbing season both in Alaska and the Yukon, where some of the highest mountains on the continent are located. While much of the officially sponsored mountaineering activity was concentrated in the border mountains between Alaska and the Yukon, there was intense activity all over Alaska as well. More information is now available on the first winter ascent of Mount McKinley mentioned in A.J. 72. 329. The team of eight was inter national in scope, a Frenchman, Swiss, German, Japanese, and New Zealander, the rest Americans. The successful group of three reached the summit on February 28 in typical Alaskan weather, -62° F. and winds of 35-40 knots. On their return they were stormbound at Denali Pass camp, I7,3oo ft. for seven days. For the forty days they were on the mountain temperatures averaged -35° to -40° F. (A.A.J. I6. 2I.) One of the most important attacks on McKinley in the summer of I967 was probably the three-pronged assault on the South face by the three parties under the general direction of Boyd Everett (A.A.J. I6. IO). The fourteen men flew in to the South east fork of the Kahiltna glacier on June 22 and split into three groups for the climbs. -

Resedimentation of the Late Holocene White River Tephra, Yukon Territory and Alaska

Resedimentation of the late Holocene White River tephra, Yukon Territory and Alaska K.D. West1 and J.A. Donaldson2 Carleton University3 West, K.D. and Donaldson, J.A. 2002. Resedimentation of the late Holocene White River tephra, Yukon Territory and Alaska. In: Yukon Exploration and Geology 2002, D.S. Emond, L.H. Weston and L.L. Lewis (eds.), Exploration and Geological Services Division, Yukon Region, Indian and Northern Affairs Canada, p. 239-247. ABSTRACT The Wrangell region of eastern Alaska represents a zone of extensive volcanism marked by intermittent pyroclastic activity during the late Holocene. The most recent and widely dispersed pyroclastic deposit in this area is the White River tephra, a distinct tephra-fall deposit covering 540 000 km2 in Alaska, Yukon, and the Northwest Territories. This deposit is the product of two Plinian eruptions from Mount Churchill, preserved in two distinct lobes, created ca. 1887 years B.P. (northern lobe) and 1147 years B.P. (eastern lobe). The tephra consists of distal primary air-fall deposits and proximal, locally resedimented volcaniclastic deposits. Distinctive layers such as the White River tephra provide important chronostratigraphic control and can be used to interpret the cultural and environmental impact of ancient large magnitude eruptions. The resedimentation of White River tephra has resulted in large-scale terraces, which fl ank the margins of Klutlan Glacier. Preliminary analysis of resedimented deposits demonstrates that the volcanic stratigraphy within individual terraces is complex and unique. RÉSUMÉ Au cours de l’Holocène tardif, des matériaux pyroclastiques ont été projetés lors d’importantes et nombreuses éruptions volcaniques, dans la région de Wrangell de l’est de l’Alaska. -

Breasts on the West Buttress Climbing the Great One for a Great Cause

Breasts on the West Buttress Climbing the Great One for a great cause Nancy Calhoun, Sheldon Kerr, Libby Bushell A Ritt Kellogg Memorial Fund Proposal Calhoun, Kerr, Bushell; BOTWB 24 Table of Contents Mission Statement and Goals 3 Libby’s Application, med. form, agreement 4-8 Libby’s Resume 9-10 Nancy’s Application, med. form, agreement 11-15 Nancy’s Resume 16-17 Sheldon’s Application, med. form, agreement 18-23 Sheldon’s Resume 24-25 Ritt Kellogg Fund Agreement 26 WFR Card copies 27 Travel Itinerary 28 Climbing Itinerary 29-34 Risk Management 35-36 Minimum Impact techniques 37 Gear List 38-40 First Aid Contents 41 Food List 42-43 Maps 44 Final Budget 45 Appendix 46-47 Calhoun, Kerr, Bushell; BOTWB 24 Breasts on the West Buttress: Mission Statement It may have started with the simple desire to climb North America’s tallest peak, but with a craving to save the world a more pressing concern on the minds of three Colorado College women (a Vermonter, an NC southern gal, and a life-long Alaskan), we realized that climbing Denali could and should be only a mere stepping stone to the much greater task at hand. Thus, we’ve teamed up with the American Breast Cancer Foundation, an organization that is doing their part to save our world, one breast at a time, in order to do our part, in hopes of becoming role models and encouraging the rest of the world to do their part too. So here’s our plan: We are going to climb Denali (Mount McKinley) via the West Buttress route in June of 2006. -

North America Summary, 1968

240 CLIMBS A~D REGIONAL ?\OTES North America Summary, 1968. Climbing activity in both Alaska and Canada subsided mar kedly from the peak in 1967 when both regions were celebrating their centen nials. The lessened activity seems also to have spread to other sections too for new routes and first ascents were considerably fewer. In Alaska probably the outstanding climb from the standpoint of difficulty was the fourth ascent of Mount Foraker, where a four-man party (Warren Bleser, Alex Birtulis, Hans Baer, Peter Williams) opened a new route up the central rib of the South face. Late in June this party flew in from Talkeetna to the Lacuna glacier. By 11 July they had established their Base Camp at the foot of the South face and started up the rib. This involved 10,000 ft of ice and rotten rock at an angle of 65°. In the next two weeks three camps were estab lished, the highest at 13,000 ft. Here, it was decided to make an all-out push for the summit. On 24 July two of the climbers started ahead to prepare a route. In twenty-eight hours of steady going they finally reached a suitable spot for a bivouac. The other two men who started long after them reached the same place in ten hours of steady going utilising the steps, fixed ropes and pitons left by the first party. After a night in the bivouac, the two groups then contin ued together and reached the summit, 17,300 ft, on 25 July. They were forced to bivouac another night on the return before reaching their high camp. -

Wrangell-St. Elias Alaska

Wrangell - St. Elias National Park Service National Park and National Preserve U.S. Department of the Interior Wrangell-St. Elias Alaska The wildness of Wrangell-St. Elias National Park The Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation vest harbor seals, which feed on fish and In late summer, black and brown bears, drawn and Preserve is uncompromising, its geography Act (ANILCA) of 1980 allows the subsistence marine invertebrates. These species and many by ripening soapberries, frequent the forests awe-inspiring. Mount Wrangell, namesake of harvest of wildlife within the park, and preserve more are key foods in the subsistence diet of and gravel bars. Human history here is ancient one of the park's four mountain ranges, is an and sport hunting only in the preserve. Hunters the Ahtna and Upper Tanana Athabaskans, and relatively sparse, and has left a light imprint active volcano. Hundreds of glaciers and ice find Dall's sheep, the park's most numerous Eyak, and Tlingit peoples. Local, non-Native on the immense landscape. Even where people fields form in the high peaks, then melt into riv large mammal, on mountain slopes where they people also share in the bounty. continue to hunt, fish, and trap, most animal, ers and streams that drain to the Gulf of Alaska browse sedges, grasses, and forbs. Sockeye, Chi fish, and plant populations are healthy and self and the Bering Sea. Ice is a bridge that connects nook, and Coho salmon spawn in area lakes and Long, dark winters and brief, lush summers lend regulati ng. For the species who call Wrangell the park's geographically isolated areas. -

Spring/ Summer 2018

CATALOG SPRING/ SUMMER 2018 S18_Cover_Alt.indd 2 8/30/17 11:13 AM WHEN THE WORLD SUDDENLY CHANGES “Give him to us! We will kill him!” About one hundred belligerent men had gathered in front of the tent, calling for me. Greg Vernovage, an American mountain guide, and Melissa (Arnot) guarded the tent and tried to keep the Sherpas at bay. A lone Sherpa, Pang Nuru, was standing next to them. He had nothing to do with us but was obviously perturbed by the situation and knew that this was just not right. I could hear a fierce discussion. The Sherpas ordered me to come out. I would be the first they would beat to death, and when they had finished with me they would go for the other two. I felt powerless and could not see a way out. How could we possibly turn the situation into our favor? What would happen to us? It was over. I couldn’t do anything. My hands were tied. I thought about how ridiculous the situation was. How many expeditions had I been on and then come back from in one piece? How many critical situations had I survived? And now I was crouching in a tent on Mount Everest, just about to be lynched by a mob of Sherpas. This was impossible and the whole situation so absurd that I had no hope. The Sherpas were incalculable, but I would probably not survive. I started to imagine how my life would end by stoning. —Excerpt from Ueli Steck: My Life in Climbing MOUNTAINEERS BOOKS is the publishing division of The Mountaineers, a nonprofit membership organization that has been a leader in outdoor education for more than 100 years. -

Subject Index

Subject Index NOTE: This index lists Abrams, Pete 21:3 Lands Conservation Act Aleutian Islands 1:4, 3:2, 21:2, 22:2, 23:2 Barnette, E.T. 22:1 most of the subjects Active, John 6:3 (ANILCA) 8:4, 18:3, 3:4, 5:4, 7:2, 7:3, 9:1, Arctic 3:2, 5:4, 6:2, 7:2, Barren Islands 19:3 Adak Island 7:3, 22:2, 19:3, 20:2, 20:3 10:3, 13:2, 18:2, 18:4, 9:4, 12:1,12:4, 13:2, Barrow 1:1, 5:4, 16:2, and people The Alaska 22:4 Alaska Native Arts and 19:2, 21:1, 21:3, 21:4, 20:3 19:2, 21:3, 25:4 Geographic Society has Admiralty Island 1:3, 5:2, Crafts 6:1, 6:3, 7:3, 8:3, 22:2, 22:4, 24:4, 25:4 Arctic Circle 7:1, 7:2, Barter Island 16:2, 20:3 covered in its first 100 7:2, 8:4, 18:3, 20:2, 9:2, 11:3, 12:3, 16:2, Aleutian Islands National 10:4 Bats 8:2, 19:3 issues. The numbers 20:4 17:3, 17:4, 20:2, 21:2, Wildlife Refuge 22:2 Arctic National Wildlife Bears 1:3, 3:4, 4:3, 8:2, (for example, 21:3) Adney, Edwin Tappan 21:4, 22:2, 23:2 Aleutian Range 9:1 Refuge 4:2, 16:2, 19:2, 9:2, 12:4, 15:3, 15:4, 19:1 Alaska Native Claims Alexandrovski 17:1 20:3, 20:4, 23:3 16:1, 17:3, 18:3, 19:2, refer to the Volume and Afognak (community) Settlement Act Alsek River 2:4, 25:2 Arctic Ocean 5:4, 16:2 19:3, 20:2, 20:3, 20:4, Number of the issue 4:3, 19:3 (ANCSA) 3:2, 4:4, 6:3, Alutiiq 12:3, 21:2, 23:2 Arctic Village 7:1, 20:3 21:1, 21:2, 21 :4, 23:4 containing that subject. -

MOUNT SAINT ELIAS As I Was Ascending Mount Logan in 1991

Mount Saint E lia s- Southwest Buttress R u e d i H o m b e r g e r , Schweizer Alpen Club In Memory of Miroslav Šmid I FIRST SAW MOUNT SAINT ELIAS as I was ascending Mount Logan in 1991. The plan to climb this magnificent peak developed slowly. As the highest coastal mountain, it would have been intriguing to climb it, by fair means, directly from sea level from the edge of the ocean at Icy Bay. In the end, however, the route won out which the International Boundary Survey Party had pioneered in 1913 but not completed. I also knew Paul Claus very well; he is the specialized glacier pilot for this region. This offered us the best solution to the transport problems with the long distances and difficult weather conditions. I was closely bound to Miroslav Šmid, called “Mira,” by a fifteen-year-long friendship. We had ventured together in the Pamir, the Alps, the Himalaya and in his own Czech technically-difficult sandstone towers. He was to be our group’s guest of honor. At the beginning of May, we all met in Anchorage and began a giant birthday party, which continued three days later on the Nebesna Glacier. Mira’s birthday and mine were only three days apart and collectively we were 99 years old. But the Nebesna Glacier does not flow off Saint Elias. Why were we there? I first informed Mira and my other friends when we were on the glacier. Paul Claus had simply set us off on the northeast side of Mount Blackburn so that we could acclimatize. -

A, Index Map of the St. Elias Mountains of Alaska and Canada Showing the Glacierized Areas (Index Map Modi- Fied from Field, 1975A)

Figure 100.—A, Index map of the St. Elias Mountains of Alaska and Canada showing the glacierized areas (index map modi- fied from Field, 1975a). B, Enlargement of NOAA Advanced Very High Resolution Radiometer (AVHRR) image mosaic of the St. Elias Mountains in summer 1995. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration image from Mike Fleming, USGS, EROS Data Center, Alaska Science Center, Anchorage, Alaska. K122 SATELLITE IMAGE ATLAS OF GLACIERS OF THE WORLD St. Elias Mountains Introduction Much of the St. Elias Mountains, a 750×180-km mountain system, strad- dles the Alaskan-Canadian border, paralleling the coastline of the northern Gulf of Alaska; about two-thirds of the mountain system is located within Alaska (figs. 1, 100). In both Alaska and Canada, this complex system of mountain ranges along their common border is sometimes referred to as the Icefield Ranges. In Canada, the Icefield Ranges extend from the Province of British Columbia into the Yukon Territory. The Alaskan St. Elias Mountains extend northwest from Lynn Canal, Chilkat Inlet, and Chilkat River on the east; to Cross Sound and Icy Strait on the southeast; to the divide between Waxell Ridge and Barkley Ridge and the western end of the Robinson Moun- tains on the southwest; to Juniper Island, the central Bagley Icefield, the eastern wall of the valley of Tana Glacier, and Tana River on the west; and to Chitistone River and White River on the north and northwest. The boundar- ies presented here are different from Orth’s (1967) description. Several of Orth’s descriptions of the limits of adjacent features and the descriptions of the St.