The SCERTS Model a Transactional, Family-Centered Approach to Enhancing Communication and Socioemotional Abilities of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ASHLING HOUSE Adel | North Leeds ASHLING HOUSE Back Church Lane, Adel Leeds LS16 8DW

listerhaigh.co.uk ASHLING HOUSE Adel | North Leeds ASHLING HOUSE Back Church Lane, Adel Leeds LS16 8DW Central Leeds 7 miles, Central Bradford 10 miles, Harrogate 11 miles, Wetherby 12 miles AN ELEGANT DISCREETLY SITUATED AND LISTED GEORGIAN HOUSE ENJOYING A PRIVATE YET CONVENIENT SETTING ON THE NORTHERN EDGE OF LEEDS IN WONDERFUL FORMAL GROUNDS OF OVER AN ACRE Accommodation Reception Hall • Cloakrooms • Drawing Room • Dining Room Sitting Room • Conservatory • Breakfast Kitchen • Utility and Pantry Central Landing • Master Bedroom with En Suite and Dressing Room Guest Bedroom with En Suite • 2 Further Double Bedrooms House Bathroom • Garaging Exquisite Formal Gardens and Grounds of Over 1 Acre Rydal House, 5 Princes Square, Harrogate North Yorkshire, HG1 1ND Tel: 01423 730700 [email protected] listerhaigh.co.uk Situation Ashling House is a North Leeds hidden gem situated on the northern edge of the city near Headingley Golf Club and close to an extensive range of recreational amenities and day-to-day facilities in Adel. The property faces south west and sits in delightful landscaped grounds that afford a high degree of privacy as one would expect with a property of this calibre. The discreet nature of the setting belies its convenience with Leeds city centre some 7 miles to the south east and within commuting distance of the West Yorkshire conurbation. For travel further afield Leeds Bradford airport is a 10/15 minute drive and for those with more country orientated pursuits Ashling House is quite literally on the edge of Leeds and so within a matter of a few minutes of country walks around the likes of Eccup reservoir, Golden Acre Park and the wider countryside of Lower Wharfedale. -

Display Wetherby

Welcome to Display Wetherby Hello, we are Display UK, part of the Smur�t Kappa Group. When you visit a Display UK site you will notice how we pride ourselves on commitment to our health and safety policies. Please take time to read our visitor safety notices and take care travelling to our site. Above all, we wish you a great visit. Please enjoy your visit 46 A168 cars A1(M) Scriftain Lane HGVs Wetherby A168 A1(M) Sandbeck Approach B1224 Sandbeck Lane, Wetherby, Yorkshire, LS22 7YD B6164 W Tel: 01937 868200 ether b B1224 y Ro B1224 a d B1224 From the North: WE B1224 Leave the A1(M) at Junction 46, take the B1224 exit signed D H earne Cr ud E ARE s s on York/Wetherby. At the roundabout take the 4th exit onto B1224. k G South Vi D eersto W a ay r of de t n Turn left at the next roundabout onto A168. Follow this road, at the n s e e HERE w A168 Ri d g roundabout take the 3rd exit onto Sandbeck Lane. Destination will e Sandbeck Lane Deighton Bar 46 be on the right. e Kirk Deighton Deighton h Yorkshir HarrogateNort Gates Primary eeds B1224 y L R School Wetherb a cec Badger o urse Fos Hunters W s venue k B A W e n ndbeck Lane e ppleb ood G Sa From the South: c h Ai w al n ood Ba y W sty Vie k w ood l a A168 Take the M1 North, keep left at the fork to stay on the M1, follow d ay e Otter Ri w s signs for Leeds (East). -

Nethermoor View OTLEY ROAD, GUISELEY LS20 8BT

Nethermoor View OTLEY ROAD, GUISELEY LS20 8BT Prices from £320,000 www.daleeddison.co.uk Nethermoor View The exclusive development Nethermoor View is situated in a convenient location in the ever popular village of Guiseley. Built by local developers, Yorkshire Homes Ltd, the development consists of five stone-built townhouses. Plots 1-4 are The Chevin house type and offer spacious yet versatile living space. Plot 5 is The Wharfedale and offers larger accommodation to the ground floor with a superb living/kitchen area and an enhanced specification. On the first floor, each home offers the master bedroom with ensuite shower room, an additional double bedroom, a study and a house bathroom whilst to the second floor there are a further two bedrooms and shower room. Outside, each property enjoys a private rear garden backing onto the cricket ground, with the Wharfedale boasting a larger garden. Each home has private car parking spaces approached from the courtyard entrance to the front. With gas fired central heating and uPVC double glazing the Chevin houses have attractive French doors to the rear, whilst The Wharfedale enjoys aluminium bi-fold doors. Each home is offered with the benefit of the Government back Help to Buy scheme and benefits from a 10 year NHBC warranty. Guiseley What determines a great place to live? Good amenities and transport links, impressive schools, a good range of shops and obviously, nice houses! These are some of the key factors homebuyers look for in a location, and Guiseley fulfils all these requirements and more! Add a dash of historical interest, great community spirit, easy access to the countryside, as well as having one of the country’s liveliest cities on your doorstep, and it’s easy to see why Nethermoor View is a great place to live. -

Guiseley • Horsforth • Wetherby Woodhouse • Alwoodley • Seacroft

FOLD BACK COVER FOLD FRONT COVER GUISELEY Music Centre Want to learn to play an instrument or sing? Guiseley School, Head of Centre: Sarah Baker Already play but want to improve? Fieldhead Road, [email protected] LS20 8DT 07545 603 952 Get expert tuition and friendly support at Leeds Music Centres. HORSFORTH Music Centre Horsforth School, Head of Centre: Alex Wibrew The Music Centres run on Saturday mornings Lea Lane East, [email protected] LS18 5RF 07545 603 953 at venues all over Leeds. All ages are welcome, from under-5s to over-60s. We have something WETHERBY Music Centre Wetherby High School, Head of Centre: Paula Brookes for everyone, from fun beginner groups to Hallfield Lane, [email protected] advanced ensembles, covering all styles and LS22 6JS 07545 603 951 levels of experience. NORTH LEEDS Music Centre Allerton C of E Primary Head of Centre: Mark Sturdy FREE INSTRUMENT HIRE Want to try out School, Lingfield [email protected] a new instrument? We can provide a year’s Approach, LS17 7HL 07545 603 957 / 0113 378 2850 free-of-charge instrument hire for beginners Some classes may also be available on Thursday evenings at Leeds City Academy – call/email for details (subject to availability). After the first year a small STEEL PAN Music Centre charge applies. Leeds City Academy, Head of Centre: Victoria Jaquiss Woodhouse Cliff, [email protected] ENROLMENT Music Centres enrol on the morning LS6 2LG 07725 044 596 of Saturday 10th September 2016. Please see EaST LEEDS Music Centre www.artformsleeds.co.uk for details of times, or Leeds East Academy, call 0113 378 2850. -

Garforth and Church Fenton

High Speed Two Phase 2b ww.hs2.org.uk October 2018 Working Draft Environmental Statement High Speed Rail (Crewe to Manchester and West Midlands to Leeds) Working Draft Environmental Statement Volume 2: Community Area report | Volume 2 | LA16 LA16: Garforth and Church Fenton High Speed Two (HS2) Limited Two Snowhill, Snow Hill Queensway, Birmingham B4 6GA Freephone: 08081 434 434 Minicom: 08081 456 472 Email: [email protected] H27 hs2.org.uk October 2018 High Speed Rail (Crewe to Manchester and West Midlands to Leeds) Working Draft Environmental Statement Volume 2: Community Area report LA16: Garforth and Church Fenton H27 hs2.org.uk High Speed Two (HS2) Limited has been tasked by the Department for Transport (DfT) with managing the delivery of a new national high speed rail network. It is a non-departmental public body wholly owned by the DfT. High Speed Two (HS2) Limited, Two Snowhill Snow Hill Queensway Birmingham B4 6GA Telephone: 08081 434 434 General email enquiries: [email protected] Website: www.hs2.org.uk A report prepared for High Speed Two (HS2) Limited: High Speed Two (HS2) Limited has actively considered the needs of blind and partially sighted people in accessing this document. The text will be made available in full on the HS2 website. The text may be freely downloaded and translated by individuals or organisations for conversion into other accessible formats. If you have other needs in this regard please contact High Speed Two (HS2) Limited. © High Speed Two (HS2) Limited, 2018, except where otherwise stated. Copyright in the typographical arrangement rests with High Speed Two (HS2) Limited. -

Download Original Attachment

Building Name Address 1 Address 2 Address 3 Address 4 Address 5 Postcode Building Use Tenure Type Airedale House Airedale House Royd Ings Avenue KEIGHLEY West Yorkshire BD21 4BZ Police Station Freehold Denholme Contact Point, Mechanics Inst Denholme Contact Point Mechanics Institute, Main Street Denholme BRADFORD West Yorkshire BD13 4BL Contact Point Leasehold Dudley Hill Centre Dudley Hill Centre Harry Street BRADFORD West Yorkshire BD4 9PH Support Office Freehold Eccleshill Police Station Eccleshill Police Station Javelin House Javelin Close BRADFORD West Yorkshire BD10 8SD Police Station Freehold Haworth Contact Point Haworth Contact Point 28 Changegate Haworth BRADFORD West Yorkshire BD22 8DY Contact Point Freehold Ilkley Police Station Ilkley Police Station Riddings Road ILKLEY West Yorkshire LS29 9LU Police Station Freehold New Park Road 24A New Park Road Queensbury BRADFORD West Yorkshire BD13 2EU Neighbourhood Policing Freehold Shipley Police Station Shipley Police Station Manor Lane SHIPLEY West Yorkshire BD18 3RJ Police Station Freehold Toller Lane Police Station Toller Lane Police Station Lawcroft House, Toller Lane Lillycroft Road BRADFORD West Yorkshire BD9 5AF Police Station Freehold Trafalgar House Trafalgar House Nelson Street BRADFORD West Yorkshire BD5 0EW Police Station Freehold Brighouse Police Station Brighouse Police Station Bradford Road BRIGHOUSE West Yorkshire HD6 4AA Police Station Freehold Halifax Police Station Halifax Police Station Richmond Close HALIFAX West Yorkshire HX1 5TW Police Station Freehold Todmorden -

Desserts Drinks

Desserts Drinks Extra Tea or Coffee per person £1.05 Banana Split £4.95 Sliced Banana on a bed of jelly, soft whipped ice cream, with cream SPECIALITY COFFEES Homemade Sherry Trifle £4.95 Cappuccino £2.40 Blend of espresso with foamed milk and a dusting of chocolate (Contains alcohol) Espresso £2.40 Soft Whipped Ice Cream Intense shot of fresh coffee With a choice of chocolate, raspberry, strawberry or butterscotch sauce Latte £2.40 Combination of espresso and steamed milk with a dash of foam Large £3.50 Regular £2.40 Cafe Mocha £2.40 Espresso blended with chocolate topped with steamed milk Mandarin Surprise £4.95 Hot Chocolate £2.40 Combination of chocolate and steamed milk Mandarin oranges with a soft whipped ice cream, topped with butterscotch sauce Brandy Snap Dream £4.95 DRINKS BELOW 5% SUGAR (per 100ml) Brandy Snap, soft whipped ice cream, cream and butterscotch sauce Bottled Coke Zero 330ml £2.55 Bottled Sprite Zero 330ml £2.55 Hot Cherry Surprise £4.95 330ml Hot Cherries, soft whipped ice cream, topped with cream Bottled Fanta Zero £2.55 Bottled Diet Coke 330ml £2.55 Hot Chocolate Fudge Cake £4.95 J2O £2.90 Served with cream or ice cream Schweppes Slimline Tonic 200ml £1.95 Schweppes Soda Water 200ml £1.95 Hot Chocolate Banana Fudge Sundae £4.95 Chocolate sponge, toffee and chocolate sauce with banana and ice cream Bottled Harrogate Spa Mineral Water £2.10 Homemade Treacle Sponge £4.95 DRINKS OVER 5% SUGAR (per 100ml) Served with custard or ice cream Bottled Coke 330ml £2.70 Bottled Sprite 330ml £2.70 Homemade Jam & Coconut Sponge -

Barwick in Elmet and Scholes Neighbourhood Deevelopment Plan

WETHERBY NEIGHBOURHOOD DEVELOPMENT PLAN Consultation Statement January 2018 0 CONTENTS 1. Introduction 2. Compliance with Neighbourhood Development Plan Regulations 3. Consultation on Neighbourhood Planning 4. A description of the process of how the issues and concerns have been considered 5. Highlights of the key issues that emerged to influence the development of policies in the proposed Neighbourhood Development Plan 6. Conclusion Appendices Appendix 1: Initial Consultation Responses Appendix 2: Results from survey conducted across November & December 2013 Appendix 3: Summary of feedback from young people’s focus groups Appendix 4: Summary of business survey results from February 2014 Appendix 5: Results and feedback from Regulation 14 pre- submission consultation Appendix 6: Weblinks to Wetherby News articles & Facebook posts Table 1: Summary of NDP steering group meetings Table 2: List of statutory consultees 1 1. Introduction Wetherby Town Council are responsible for the production of this Neighbourhood Plan. This is in line with the aims and purposes of neighbourhood planning, as set out in the Localism Act (2011), the National Planning Policy Framework (2012) and Planning Practice Guidance (2014). Wetherby Town Council made the decision to begin the development of a Neighbourhood Development Plan in October 2012. A separate neighbourhood plan steering group (NDPSG) was established following a call for volunteers in January 2013. It was proposed from the outset that the neighbourhood plan boundary – the neighbourhood area - would follow the Town Council boundary. The Town Council’s application underwent the statutory six-week consultation period which allowed people who live, work and conduct business to comment on the application and the area boundary. -

Barwick in Elmet ~ Flat 1, 24 Main Street, LS15 4JQ

Barwick In Elmet ~ Flat 1, 24 Main Street, LS15 4JQ A genuinely spacious and beautifully Located within the conservation area in the presented two bedroom first floor heart of the village apartment with large roof terrace Two double bedrooms and two bathrooms Lounge with feature fireplace and log burner garden and rear garage situated in the conservation area of this sought after Dining kitchen village, noted for its maypole and Garage and additional dedicated off road success within the Village in Bloom parking space competition. No upward chain. Large private roof terrace with views of the historic church and maypole No service charge payable £1 69,900 OFFERS OVER FOR THE LEASEHOLD MISREPRESENTATION ACT CHARTERED SURVEYORS 01937 582731 Renton & Parr Ltd for themselves and for the Vendors or lessors of thi s property whose agents they give notice that :- ESTATE AGENTS [email protected] 1. The particul ar s are set out as a gener al outline only f or the gui dance of intending purchaser s or lessees, and do not VALUERS rentonandparr.co.uk constitute, nor constitute part of, an offer or contr act. 2. All descripti ons, di mensions, references to conditi on and necessary per mission for use and occupati on, and other details ar e given in good faith and are believed to be correct but any intending purchasers or tenants shoul d not rely on them as statements or representati ons of fact but must sati sfy themselves by inspecti on or otherwise as to the correctness of each of them. 3. No per son in the empl oyment of Renton & Parr Ltd has any authority to make or give any repr esentati on or warr anty All-round excellence, all round Wetherby since 1950 whatever in relati on to thi s property. -

CASTLE FIELDS OFF KESWICK LANE, BARDSEY at Park Lane Homes, We Believe That Creating Truly Aspirational Living Is All About Attention to the Finer Details

CASTLE FIELDS OFF KESWICK LANE, BARDSEY At Park Lane Homes, we believe that creating truly aspirational living is all about attention to the finer details. That means seeking out the most exclusive locations in Yorkshire - the places served by seamless ASPIRATION ATTENTION DISTINCTION connectivity and the best schools. It means our team of in-house experts coordinate bespoke planning, design and build to achieve character and individuality, rather than ’mass produced’ properties. And it also means finishing our homes to the highest standards, with a comprehensive range of superior features and interior appointments which reflect our customers’ choices and desires. We specialise in creating new homes of genuine distinction, from substantial detached houses, barn conversions and large Victorian- style villas to elegant mews homes and luxury apartments. All properties in our unique and diverse portfolio share fundamental qualities: timeless craftsmanship, an outstanding contemporary specification and a clear focus on meeting your aspirations, achieved with that all-important eye for detail. CASTLE FIELDS OFF KESWICK LANE, BARDSEY Picture this. A secluded cul-de-sac nestled within a tranquil, idyllic village. A select collection of beautifully crafted new 4 and 5 bedroom homes, each styled and built in harmony with their scenic rural surroundings. When we imagined that picture, we focused all of our planning and design expertise on making it a reality. With the launch of Castle Fields in sought-after Bardsey village, the reality is here. LUXURY HARMONY INDIVIDUALITY SECLUSION SERENITY SPACE With generously sized plots included to each property and a mature setting overlooking open countryside, Castle Fields is a haven of seclusion, serenity and space. -

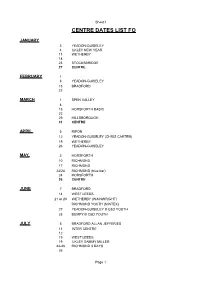

Yorkshire Centre Provisional Dates 2015

Sheet1 CENTRE DATES LIST FOR 2015/16 JANUARY 3 YEADON-GUISELEY 4 ILKLEY NEW YEAR 11 WETHERBY 18 25 STOCKSBRIDGE 27 CENTRE FEBRUARY 1 8 YEADON-GUISELEY 15 BRADFORD 22 MARCH 1 SPEN VALLEY 8 15 HORSFORTH BASIC 22 29 HILLSBOROUGH 31 CENTRE APRIL 5 RIPON 12 YEADON-GUISELEY (CHRIS CARTER) 19 WETHERBY 26 YEADON-GUISELEY MAY 3 HORSFORTH 10 RICHMOND 17 RICHMOND 23/24 RICHMOND (blue bar) 24 HORSFORTH 26 CENTRE JUNE 7 BRADFORD 14 WEST LEEDS 21 or 28 WETHERBY (WAINWRIGHT) RICHMOND YOUTH (MINTEX) 27 YEADON-GUISELEY B C&D YOUTH 28 BUMPY B C&D YOUTH JULY 5 BRADFORD ALLAN JEFFERIES 11 INTER CENTRE 12 19 WEST LEEDS 19 ILKLEY SAMMY MILLER 24-26 RICHMOND 3 DAYS 26 Page 1 Sheet1 28 CENTRE AUGUST 2 9 WEST LEEDS 16 WETHERBY 16 RICHMOND LADIES 23 YEADON-GUISELEY 30 RICHMOND B C&D YOUTH 30 RIPON NOVICE SEPTEMBER 6 SPEN VALLEY 13 WEST LEEDS (WHITE ROSE) 20 RICHMOND 27 YEADON GUISELEY ( Mel Harrison) 29 CENTRE OCTOBER 4 RIPON 11 YEADON-GUISELEY 17 RICHMOND (SCOTT) 18 25 HILLSBOROUGH (TWIN SHOCK) NOVEMBER 1 WETHERBY 7 HORSFORTH 8 NO TRIALS 15 YEADON-GUISELEY 22 24 CENTRE 29 WETHERBY DECEMBER 6 BRADFORD 13 HILLSBOROUGH 20 26 WEST LEEDS 27 WETHERBY 2016 JANUARY 3 ILKLEY NEW YEAR 10 WETHERBY 17 24 STOCKSBRIDGE 26 CENTRE A.G.M. FEBRUARY 7 YEADON-GUISELEY 14 BRADFORD 21 28 Page 2 Sheet1 MARCH 6 SPEN VALLEY 13 HORSFORTH BASIC 20 27 Page 3 Sheet1 CENTRE DATES LIST FOR 2015/16 INTERNATIONAL ARENA WEST YORKSHIRE CHAMP. TRIAL WEST YORKSHIRE CHAMP. -

Adel and Wharfedale Ward April 2019

Adel and Wharfedale ward April 2019 Health profile overview for Adel and Wharfedale ward This profile presents a high level summary of health Population age structure: 21,358 in total related data sets for the Adel and Wharfedale ward. Comparison of ward and Leeds age structures January 2019. Leeds as outline, ward shaded. This ward has a GP registered population of 21,358 Mid range Most deprived 5th Least deprived 5th with the majority of the ward population living in the 100-104 Males: 10,569 Females: 10,789 least deprived fifth of Leeds. In Leeds terms the ward 90-94 is ranked third least deprived. 80-84 The age profile of this ward is very different to Leeds, 70-74 with many more elderly people and far fewer young 60-64 adults and children. 50-54 40-44 30-34 About deprivation in this report 20-24 Deprivation throughout England is measured using the Index of 10-14 Multiple Deprivation (IMD). The IMD is the result of analysis in seven 'domains': Income, employment, education, health, 0-4 crime, barriers to housing & services, and living environment. 6% 3% 0% 3% 6% The IMD provides a score for every part of England and we use Deprivation in this ward this in Leeds to determine which areas of Leeds are most Proportions of this population within each deprivation fifth of deprived. Leeds. January 2019. Leeds is divided into five groups from the most deprived fifth of 61% Leeds the "deprived fifth", to the least. Because this divides Leeds by MSOAs, it is a slightly generalised and removes detail in very small areas.