CP Bird Collection

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Why So Many Kinds of Passerine Birds?

Letters • Why so many kinds of passerine birds? Raikow and Bledsoe (2000), in em- Slud 1976). It is unreasonable to assume the list of possible reasons for passerine bracing the null model of Slowinski that there is no underlying biological rea- success, but I would place more empha- and Guyer (1989a, 1989b), may perhaps son for this pattern and for the major sis on it than he did. be said literally to have added nothing turnover in avifaunas in the Northern It is difficult to discuss the nest-bufld- to the Kst of suggestions for why there are Hemisphere in favor of passerines after ing capabilities of passerines without re- so many species of passerine birds. When the Oligocène. sorting to anthropomorphisms such as Raikow (1986) addressed this problem Reproductive adaptations presumably "clever" or "ingenious." Is it not mar- previously and could find no key mor- made the holometabolous insects velous, however, that a highly special- phological adaptations to explain the di- (Coleóptera, Díptera, Hymenoptera, ized aerial feeder such as a cliff swallow versity of Passeriformes, the so-called Lepidoptera, and so on) the dominant (Hirundo pyrrhonota), with tiny, weak songbirds or perching birds, he despaired clade of organisms on earth. Likewise, it bill and feet, can fashion a complex nest and suggested that the problem may be appears that reproductive adaptations, out of gobs of mud fastened to a flat, only "an accident of classificatory his- not morphology, are responsible for the vertical surface? What adjective suffices tory," which brought on a storm of protest dominance of passerine birds over other to describe the nest of tailorbirds {Systematic Zoology 37: 68-76; 41: 242- orders of birds. -

Brown2009chap67.Pdf

Swifts, treeswifts, and hummingbirds (Apodiformes) Joseph W. Browna,* and David P. Mindella,b Hirundinidae, Order Passeriformes), and between the aDepartment of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology & University nectivorous hummingbirds and sunbirds (Family Nec- of Michigan Museum of Zoology, 1109 Geddes Road, University tariniidae, Order Passeriformes), the monophyletic sta- b of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-1079, USA; Current address: tus of Apodiformes has been well supported in all of the California Academy of Sciences, 55 Concourse Drive Golden Gate major avian classiA cations since before Fürbringer (3). Park, San Francisco, CA 94118, USA *To whom correspondence should be addressed (josephwb@ A comprehensive historical review of taxonomic treat- umich.edu) ments is available (4). Recent morphological (5, 6), genetic (4, 7–12), and combined (13, 14) studies have supported the apodiform clade. Although a classiA cation based on Abstract large DNA–DNA hybridization distances (4) promoted hummingbirds and swiJ s to the rank of closely related Swifts, treeswifts, and hummingbirds constitute the Order orders (“Trochiliformes” and “Apodiformes,” respect- Apodiformes (~451 species) in the avian Superorder ively), the proposed revision does not inP uence evolu- Neoaves. The monophyletic status of this traditional avian tionary interpretations. order has been unequivocally established from genetic, One of the most robustly supported novel A ndings morphological, and combined analyses. The apodiform in recent systematic ornithology is a close relation- timetree shows that living apodiforms originated in the late ship between the nocturnal owlet-nightjars (Family Cretaceous, ~72 million years ago (Ma) with the divergence Aegothelidae, Order Caprimulgiformes) and the trad- of hummingbird and swift lineages, followed much later by itional Apodiformes. -

Similarities in Body Size Distributions of Small-Bodied Flying Vertebrates

Evolutionary Ecology Research, 2004, 6: 783–797 Similarities in body size distributions of small-bodied flying vertebrates Brian A. Maurer,* James H. Brown, Tamar Dayan, Brian J. Enquist, S.K. Morgan Ernest, Elizabeth A. Hadly, John P. Haskell, David Jablonski, Kate E. Jones, Dawn M. Kaufman, S. Kathleen Lyons, Karl J. Niklas, Warren P. Porter, Kaustuv Roy, Felisa A. Smith, Bruce Tiffney and Michael R. Willig National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis (NCEAS), Working Group on Body Size in Ecology and Paleoecology, 735 State Street, Suite 300, Santa Barbara, CA 93101-5504, USA ABSTRACT Since flight imposes physical constraints on the attributes of a flying organism, it is expected that the distribution of body sizes within clades of small-bodied flying vertebrates should share a similar pattern that reflects these constraints. We examined patterns in similarities of body mass distributions among five clades of small-bodied endothermic vertebrates (Passeriformes, Apodiformes + Trochiliformes, Chiroptera, Insectivora, Rodentia) to examine the extent to which these distributions are congruent among the clades that fly as opposed to those that do not fly. The body mass distributions of three clades of small-bodied flying vertebrates show significant divergence from the distributions of their sister clades. We examined two alternative hypotheses for similarities among the size frequency distributions of the five clades. The hypothesis of functional symmetry corresponds to patterns of similarity expected if body mass distributions of flying clades are constrained by similar or identical functional limitations. The hypothesis of phylogenetic symmetry corresponds to patterns of similarity expected if body mass distributions reflect phylogenetic relationships among clades. -

1 Husbandry Guidelines Apodiformes Hummingbirds-Trochilidae Karen

Husbandry Guidelines Apodiformes Hummingbirds-Trochilidae Karen Krebbs, Conservation Biologist / Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum / Tucson, AZ Dave Rimlinger, Curator of Ornithology / San Diego Zoo / San Diego, CA Michael Mace, Curator of Ornithology / San Diego Wild Animal Park / Escondido, CA September, 2002 1. ACQUISITION AND ACCLIMATIZATION Sources of birds & acclimatization procedures - In the United States local species of hummingbirds can be collected with the proper permits. The Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum usually has species such as Anna's (Calypte anna), Costa's (Calypte costae), and Broad-billed (Cynanthus latirostris) for surplus each year if these species have nested in their Hummingbird Exhibit. In addition to keeping some native species, the San Diego Zoo has tried to maintain several exotic species such as Sparkling violet-ear (Colibri coruscans), Emerald (Amazilia amazilia), Oasis (Rhodopis vesper), etc. The San Diego Wild Animal Park has a large mixed species glass walk-through enclosure and has kept and produced hummingbirds over the years. All hummingbirds are on Appendix II of CITES and thus are covered under the Wild Bird Conservation Act (WBCA). An import permit from USFWS and an export permit from the country of origin must be obtained prior to the importation. Permits have been granted in the past, but currently it is difficult to find a country willing to export hummingbirds. Hummingbirds are more commonly kept in European collections, particularly private collections, and could be a source for future imports. Weighing Hummingbirds can be placed in a soft mesh bag and weighed with a spring scale. Electronic digital platform scales can also be used. A small wooden crate with a wire mesh front can also be used for weighing. -

2020 National Bird List

2020 NATIONAL BIRD LIST See General Rules, Eye Protection & other Policies on www.soinc.org as they apply to every event. Kingdom – ANIMALIA Great Blue Heron Ardea herodias ORDER: Charadriiformes Phylum – CHORDATA Snowy Egret Egretta thula Lapwings and Plovers (Charadriidae) Green Heron American Golden-Plover Subphylum – VERTEBRATA Black-crowned Night-heron Killdeer Charadrius vociferus Class - AVES Ibises and Spoonbills Oystercatchers (Haematopodidae) Family Group (Family Name) (Threskiornithidae) American Oystercatcher Common Name [Scientifc name Roseate Spoonbill Platalea ajaja Stilts and Avocets (Recurvirostridae) is in italics] Black-necked Stilt ORDER: Anseriformes ORDER: Suliformes American Avocet Recurvirostra Ducks, Geese, and Swans (Anatidae) Cormorants (Phalacrocoracidae) americana Black-bellied Whistling-duck Double-crested Cormorant Sandpipers, Phalaropes, and Allies Snow Goose Phalacrocorax auritus (Scolopacidae) Canada Goose Branta canadensis Darters (Anhingidae) Spotted Sandpiper Trumpeter Swan Anhinga Anhinga anhinga Ruddy Turnstone Wood Duck Aix sponsa Frigatebirds (Fregatidae) Dunlin Calidris alpina Mallard Anas platyrhynchos Magnifcent Frigatebird Wilson’s Snipe Northern Shoveler American Woodcock Scolopax minor Green-winged Teal ORDER: Ciconiiformes Gulls, Terns, and Skimmers (Laridae) Canvasback Deep-water Waders (Ciconiidae) Laughing Gull Hooded Merganser Wood Stork Ring-billed Gull Herring Gull Larus argentatus ORDER: Galliformes ORDER: Falconiformes Least Tern Sternula antillarum Partridges, Grouse, Turkeys, and -

Airbirds: Adaptative Strategies to the Aerial Lifestyle from a Life History Perspective

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1998 Airbirds: Adaptative Strategies to the Aerial Lifestyle From a Life History Perspective. Manuel Marin-aspillaga Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Marin-aspillaga, Manuel, "Airbirds: Adaptative Strategies to the Aerial Lifestyle From a Life History Perspective." (1998). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 6849. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/6849 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type o f computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy subm itted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B

Downloaded from http://rstb.royalsocietypublishing.org/ on February 29, 2016 Feeding innovations in a nested phylogeny of Neotropical passerines rstb.royalsocietypublishing.org Louis Lefebvre, Simon Ducatez and Jean-Nicolas Audet Department of Biology, McGill University, 1205 avenue Docteur Penfield, Montre´al, Que´bec, Canada H3A 1B1 Several studies on cognition, molecular phylogenetics and taxonomic diversity Research independently suggest that Darwin’s finches are part of a larger clade of speciose, flexible birds, the family Thraupidae, a member of the New World Cite this article: Lefebvre L, Ducatez S, Audet nine-primaried oscine superfamily Emberizoidea. Here, we first present a new, J-N. 2016 Feeding innovations in a nested previously unpublished, dataset of feeding innovations covering the Neotropi- phylogeny of Neotropical passerines. Phil. cal region and compare the stem clades of Darwin’s finches to other neotropical Trans. R. Soc. B 371: 20150188. clades at the levels of the subfamily, family and superfamily/order. Both in http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2015.0188 terms of raw frequency as well as rates corrected for research effort and phylo- geny, the family Thraupidae and superfamily Emberizoidea show high levels of innovation, supporting the idea that adaptive radiations are favoured when Accepted: 25 November 2015 the ancestral stem species were flexible. Second, we discuss examples of inno- vation and problem-solving in two opportunistic and tame Emberizoid species, One contribution of 15 to a theme issue the Barbados bullfinch Loxigilla barbadensis and the Carib grackle Quiscalus ‘Innovation in animals and humans: lugubris fortirostris in Barbados. We review studies on these two species and argue that a comparison of L. -

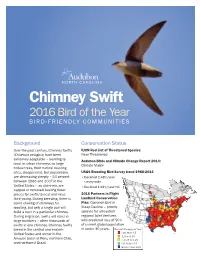

Chimney Swift 2016 Bird of the Year BIRD-FRIENDLY COMMUNITIES

Chimney Swift 2016 Bird of the Year BIRD-FRIENDLY COMMUNITIES Background Conservation Status Over the past century, Chimney Swifts IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: (Chaetura pelagica) have been Near Threatened extremely adaptable – learning to Audubon Birds and Climate Change Report 2014: roost in urban chimneys as large Climate Stable hollow trees, their natural roosting sites, disappeared. But populations USGS Breeding Bird Survey trend 1966-2013 are decreasing steeply – 53 percent •Declined 2.48%/year between 1966 and 2007 in the survey-wide United States – as chimneys are •Declined 1.61%/year NC capped or removed, leaving fewer places for swifts to nest and raise 2016 Partners in Flight their young. During breeding, there is Landbird Conservation some sharing of chimneys for Plan: Common Bird in roosting, but only a single pair will Steep Decline – priority build a nest in a particular chimney. species for all eastern During migration, swifts will roost in regional Joint Ventures large numbers – often thousands of with predicted loss of 50% swifts in one chimney. Chimney Swifts of current global population breed in the central and eastern in under 30 years. Percent Change per Year United States and winter in the Less than 1.5 -1.5 to -0.25 Amazon basin of Peru, northern Chile, > -0.25 to 0.25 and northwest Brazil. > 0.25 to +1.5 Greater than +1.5 Four Ways You Can Help 1 Keep Your Chimney Open The practice of capping older chimneys makes 2 them inaccessible to swifts. One solution is to Be a Citizen hire a chimney sweep to Scientist cap the chimney in Report nesting and 3 November and open it up roosting sites at again before Chimney Construct A nc.audubon.org. -

(Diptera: Muscidae): an Invasive Avian Parasite on the Galápagos Islands Lauren K

Chapter Taxonomic Shifts in Philornis Larval Behaviour and Rapid Changes in Philornis downsi Dodge & Aitken (Diptera: Muscidae): An Invasive Avian Parasite on the Galápagos Islands Lauren K. Common, Rachael Y. Dudaniec, Diane Colombelli-Négrel and Sonia Kleindorfer Abstract The parasitic larvae of Philornis downsi Dodge & Aitken (Diptera: Muscidae) were first discovered in Darwin’s finch nests on the Galápagos Islands in 1997. Larvae of P. downsi consume the blood and tissue of developing birds, caus- ing high in-nest mortality in their Galápagos hosts. The fly has been spreading across the archipelago and is considered the biggest threat to the survival of Galápagos land birds. Here, we review (1) Philornis systematics and taxonomy, (2) discuss shifts in feeding habits across Philornis species comparing basal to more recently evolved groups, (3) report on differences in the ontogeny of wild and captive P. downsi larvae, (4) describe what is known about adult P. downsi behaviour, and (5) discuss changes in P. downsi behaviour since its discovery on the Galápagos Islands. From 1997 to 2010, P. downsi larvae have been rarely detected in Darwin’s finch nests with eggs. Since 2012, P. downsi larvae have regularly been found in the nests of incubating Darwin’s finches. Exploring P. downsi ontogeny and behaviour in the larger context of taxonomic relationships provides clues about the breadth of behavioural flexibility that may facilitate successful colonisation. Keywords: Protocalliphora, Passeromyia, Philornis, nest larvae, hematophagous, subcutaneous, Darwin’s finches, Passeriformes 1. Introduction Three genera of flies within the order Diptera have larvae that parasitise avian hosts: Protocalliphora Hough (Calliphoridae), as well as Passeromyia Rodhain & Villeneuve (Muscidae) and Philornis Meinert (Muscidae). -

Learn About Texas Birds Activity Book

Learn about . A Learning and Activity Book Color your own guide to the birds that wing their way across the plains, hills, forests, deserts and mountains of Texas. Text Mark W. Lockwood Conservation Biologist, Natural Resource Program Editorial Direction Georg Zappler Art Director Elena T. Ivy Educational Consultants Juliann Pool Beverly Morrell © 1997 Texas Parks and Wildlife 4200 Smith School Road Austin, Texas 78744 PWD BK P4000-038 10/97 All rights reserved. No part of this work covered by the copyright hereon may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means – graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, or information storage and retrieval systems – without written permission of the publisher. Another "Learn about Texas" publication from TEXAS PARKS AND WILDLIFE PRESS ISBN- 1-885696-17-5 Key to the Cover 4 8 1 2 5 9 3 6 7 14 16 10 13 20 19 15 11 12 17 18 19 21 24 23 20 22 26 28 31 25 29 27 30 ©TPWPress 1997 1 Great Kiskadee 16 Blue Jay 2 Carolina Wren 17 Pyrrhuloxia 3 Carolina Chickadee 18 Pyrrhuloxia 4 Altamira Oriole 19 Northern Cardinal 5 Black-capped Vireo 20 Ovenbird 6 Black-capped Vireo 21 Brown Thrasher 7Tufted Titmouse 22 Belted Kingfisher 8 Painted Bunting 23 Belted Kingfisher 9 Indigo Bunting 24 Scissor-tailed Flycatcher 10 Green Jay 25 Wood Thrush 11 Green Kingfisher 26 Ruddy Turnstone 12 Green Kingfisher 27 Long-billed Thrasher 13 Vermillion Flycatcher 28 Killdeer 14 Vermillion Flycatcher 29 Olive Sparrow 15 Blue Jay 30 Olive Sparrow 31 Great Horned Owl =female =male Texas Birds More kinds of birds have been found in Texas than any other state in the United States: just over 600 species. -

Apodiformes: Apodidae) Breeding Near Presidente Figueiredo, Amazonas: the First Documented Record for Brazil

Revista Brasileira de Ornitologia, 16(4):398-401 NOTA dezembro de 2008 The White-chinned Swift Cypseloides cryptus (Apodiformes: Apodidae) breeding near Presidente Figueiredo, Amazonas: the first documented record for Brazil Andrew Whittaker and Steven Araújo Whittaker Conjunto Acariquara Sul. Rua Samaumas 214, 69085-410, Manaus, AM, Brasil. E-mails: [email protected] e [email protected] Recebido em 15/01/2008. Aceito em 22/09/2008. RESUMO: O taperuçu Cypseloides cryptus (Apodiformes: Apodidae) nidificando perto de Presidente Figueiredo, Amazonas: primeiro registro documentado para o Brasil. O pouco conhecido Cypseloides cryptus Zimmer, 1945 foi encontrado nidificando em duas cachoeiras situadas em locais diferentes perto de Presidente Figueiredo em julho de 2007. Um ninho predado foi coletado e depositado na coleção de aves do INPA e no outro ninho o filhote foi manipulado, medido e fotografado e colocado de volta em seu ninho. Estes registros estendem para o sul a distribuição conhecida cerca de 700 km a partir dos tepuis do sudeste da Venezuela e sudeste da Guiana. O nome sugerido para a espécie em português é Taperuçu-do-mento-branco. PALAVras-CHAVE: Amazonas, Apodidae, Brasil, cachoeira, Cypseloides cryptus, nidificação, Taperuçu-do-mento-branco, nidificação, cachoeira. KEY-WORDS: Amazonas, Apodidae, Brazil, breeding, Cypseloides cryptus, waterfall, White-chinned Swift. The distribution of the White-chinned Swift Cypsel- AW’s knowledge of the distributions of all know oides cryptus Zimmer, 1945 is poorly known with scattered Brazilian Cypseloides suggested that this record could per- records from both Central and South America. In Cen- tain to the poorly-known White-chinned Swift, which tral America records primarily originate from the Carib- had not yet been documented in Brazil, although known bean slope and lowlands of Belize, Honduras, Nicaragua, to occur and breed further north in the Guianan Shield Costa Rica and Panama. -

Developmental Origins of Mosaic Evolution in the Avian Cranium

Developmental origins of mosaic evolution in the SEE COMMENTARY avian cranium Ryan N. Felicea,b,1 and Anjali Goswamia,b,c aDepartment of Genetics, Evolution, and Environment, University College London, London WC1E 6BT, United Kingdom; bDepartment of Life Sciences, The Natural History Museum, London SW7 5DB, United Kingdom; and cDepartment of Earth Sciences, University College London, London WC1E 6BT, United Kingdom Edited by Neil H. Shubin, The University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, and approved December 1, 2017 (received for review September 18, 2017) Mosaic evolution, which results from multiple influences shaping genes. For example, manipulating the expression of Fgf8 generates morphological traits and can lead to the presence of a mixture of correlated responses in the growth of the premaxilla and palatine ancestral and derived characteristics, has been frequently invoked in in archosaurs (11). Similarly, variation in avian beak shape and describing evolutionary patterns in birds. Mosaicism implies the size is regulated by two separate developmental modules (7). hierarchical organization of organismal traits into semiautonomous Despite the evidence for developmental modularity in the avian subsets, or modules, which reflect differential genetic and develop- skull, some studies have concluded that the cranium is highly in- mental origins. Here, we analyze mosaic evolution in the avian skull tegrated (i.e., not subdivided into semiautonomous modules) (9, using high-dimensional 3D surface morphometric data across a 10, 12). In light of recent evidence that diversity in beak mor- broad phylogenetic sample encompassing nearly all extant families. phology may not be shaped by dietary factors (12), it is especially We find that the avian cranium is highly modular, consisting of seven critical to investigate other factors that shape the evolution of independently evolving anatomical regions.