Hovering and Intermittent Flight in Birds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Effects of Nestling Diet on Growth and Adult Size of Zebra Finches (Poephila Guttata )

THE AUK A QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ORNITHOLOGY VOL. 104 APRIL 1987 NO. 2 EFFECTS OF NESTLING DIET ON GROWTH AND ADULT SIZE OF ZEBRA FINCHES (POEPHILA GUTTATA ) PETER T. BOAG Departmentof Biology,Queen's University, Kingston, Ontario K7L 3N6, Canada Al•STRACT.--Manipulationof the diet of Zebra Finch (Poephilaguttata) nestlings in the laboratoryshowed that a low-quality diet reducedgrowth ratesof nine externalmorpholog- ical characters,while a high-quality diet increasedgrowth rates.The growth of plumage characterswas least affectedby diet, while growth ratesof tarsusand masswere most af- fected. The treatments also produced differencesin the adult size of experimental birds, differencesnot evident in either their parentsor their own offspring.Diet quality had the strongestimpact on adult massand tarsuslength, while plumage and beak measurements were less affected. Analysis using principal componentsand characterratios showed that the shapeof experimentalbirds was affectedby the experimentaldiets, but to a minor extent comparedwith changesin overall size. Significantshape changes involved ratiosbetween fast- and slow-growingcharacters. The ratios of charactersthat grow at similar, slow rates (e.g. beak shape) were not affected by the diets. Environmental sourcesof morphological variation should not be neglectedin studiesof phenotypicvariation in birds. Received5 June 1986, accepted30 October1986. MORPHOLOGICAL differences between indi- fitness, and weather was seen in the nonran- vidual birds are often assignedfunctional sig- dom survival of House Sparrows collected by nificance, whether those individuals are of dif- Hiram Bumpus following a winter storm ferent species,different sexes,or different-size (O'Donald 1973, Fleischer and Johnston 1982). members of the same sex (Hamilton 1961, Se- Recently, investigators have tried to dem- lander 1966,Clark 1979,James 1982). -

Why So Many Kinds of Passerine Birds?

Letters • Why so many kinds of passerine birds? Raikow and Bledsoe (2000), in em- Slud 1976). It is unreasonable to assume the list of possible reasons for passerine bracing the null model of Slowinski that there is no underlying biological rea- success, but I would place more empha- and Guyer (1989a, 1989b), may perhaps son for this pattern and for the major sis on it than he did. be said literally to have added nothing turnover in avifaunas in the Northern It is difficult to discuss the nest-bufld- to the Kst of suggestions for why there are Hemisphere in favor of passerines after ing capabilities of passerines without re- so many species of passerine birds. When the Oligocène. sorting to anthropomorphisms such as Raikow (1986) addressed this problem Reproductive adaptations presumably "clever" or "ingenious." Is it not mar- previously and could find no key mor- made the holometabolous insects velous, however, that a highly special- phological adaptations to explain the di- (Coleóptera, Díptera, Hymenoptera, ized aerial feeder such as a cliff swallow versity of Passeriformes, the so-called Lepidoptera, and so on) the dominant (Hirundo pyrrhonota), with tiny, weak songbirds or perching birds, he despaired clade of organisms on earth. Likewise, it bill and feet, can fashion a complex nest and suggested that the problem may be appears that reproductive adaptations, out of gobs of mud fastened to a flat, only "an accident of classificatory his- not morphology, are responsible for the vertical surface? What adjective suffices tory," which brought on a storm of protest dominance of passerine birds over other to describe the nest of tailorbirds {Systematic Zoology 37: 68-76; 41: 242- orders of birds. -

Brown2009chap67.Pdf

Swifts, treeswifts, and hummingbirds (Apodiformes) Joseph W. Browna,* and David P. Mindella,b Hirundinidae, Order Passeriformes), and between the aDepartment of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology & University nectivorous hummingbirds and sunbirds (Family Nec- of Michigan Museum of Zoology, 1109 Geddes Road, University tariniidae, Order Passeriformes), the monophyletic sta- b of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-1079, USA; Current address: tus of Apodiformes has been well supported in all of the California Academy of Sciences, 55 Concourse Drive Golden Gate major avian classiA cations since before Fürbringer (3). Park, San Francisco, CA 94118, USA *To whom correspondence should be addressed (josephwb@ A comprehensive historical review of taxonomic treat- umich.edu) ments is available (4). Recent morphological (5, 6), genetic (4, 7–12), and combined (13, 14) studies have supported the apodiform clade. Although a classiA cation based on Abstract large DNA–DNA hybridization distances (4) promoted hummingbirds and swiJ s to the rank of closely related Swifts, treeswifts, and hummingbirds constitute the Order orders (“Trochiliformes” and “Apodiformes,” respect- Apodiformes (~451 species) in the avian Superorder ively), the proposed revision does not inP uence evolu- Neoaves. The monophyletic status of this traditional avian tionary interpretations. order has been unequivocally established from genetic, One of the most robustly supported novel A ndings morphological, and combined analyses. The apodiform in recent systematic ornithology is a close relation- timetree shows that living apodiforms originated in the late ship between the nocturnal owlet-nightjars (Family Cretaceous, ~72 million years ago (Ma) with the divergence Aegothelidae, Order Caprimulgiformes) and the trad- of hummingbird and swift lineages, followed much later by itional Apodiformes. -

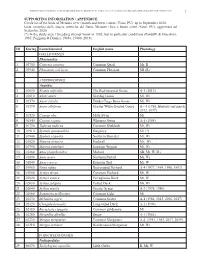

1 ID Euring Latin Binomial English Name Phenology Galliformes

BIRDS OF METAURO RIVER: A GREAT ORNITHOLOGICAL DIVERSITY IN A SMALL ITALIAN URBANIZING BIOTOPE, REQUIRING GREATER PROTECTION 1 SUPPORTING INFORMATION / APPENDICE Check list of the birds of Metauro river (mouth and lower course / Fano, PU), up to September 2020. Lista completa delle specie ornitiche del fiume Metauro (foce e basso corso /Fano, PU), aggiornata ad Settembre 2020. (*) In the study area 1 breeding attempt know in 1985, but in particolar conditions (Pandolfi & Giacchini, 1985; Poggiani & Dionisi, 1988a, 1988b, 2019). ID Euring Latin binomial English name Phenology GALLIFORMES Phasianidae 1 03700 Coturnix coturnix Common Quail Mr, B 2 03940 Phasianus colchicus Common Pheasant SB (R) ANSERIFORMES Anatidae 3 01690 Branta ruficollis The Red-breasted Goose A-1 (2012) 4 01610 Anser anser Greylag Goose Mi, Wi 5 01570 Anser fabalis Tundra/Taiga Bean Goose Mi, Wi 6 01590 Anser albifrons Greater White-fronted Goose A – 4 (1986, february and march 2012, 2017) 7 01520 Cygnus olor Mute Swan Mi 8 01540 Cygnus cygnus Whooper Swan A-1 (1984) 9 01730 Tadorna tadorna Common Shelduck Mr, Wi 10 01910 Spatula querquedula Garganey Mr (*) 11 01940 Spatula clypeata Northern Shoveler Mr, Wi 12 01820 Mareca strepera Gadwall Mr, Wi 13 01790 Mareca penelope Eurasian Wigeon Mr, Wi 14 01860 Anas platyrhynchos Mallard SB, Mr, W (R) 15 01890 Anas acuta Northern Pintail Mi, Wi 16 01840 Anas crecca Eurasian Teal Mr, W 17 01960 Netta rufina Red-crested Pochard A-4 (1977, 1994, 1996, 1997) 18 01980 Aythya ferina Common Pochard Mr, W 19 02020 Aythya nyroca Ferruginous -

Similarities in Body Size Distributions of Small-Bodied Flying Vertebrates

Evolutionary Ecology Research, 2004, 6: 783–797 Similarities in body size distributions of small-bodied flying vertebrates Brian A. Maurer,* James H. Brown, Tamar Dayan, Brian J. Enquist, S.K. Morgan Ernest, Elizabeth A. Hadly, John P. Haskell, David Jablonski, Kate E. Jones, Dawn M. Kaufman, S. Kathleen Lyons, Karl J. Niklas, Warren P. Porter, Kaustuv Roy, Felisa A. Smith, Bruce Tiffney and Michael R. Willig National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis (NCEAS), Working Group on Body Size in Ecology and Paleoecology, 735 State Street, Suite 300, Santa Barbara, CA 93101-5504, USA ABSTRACT Since flight imposes physical constraints on the attributes of a flying organism, it is expected that the distribution of body sizes within clades of small-bodied flying vertebrates should share a similar pattern that reflects these constraints. We examined patterns in similarities of body mass distributions among five clades of small-bodied endothermic vertebrates (Passeriformes, Apodiformes + Trochiliformes, Chiroptera, Insectivora, Rodentia) to examine the extent to which these distributions are congruent among the clades that fly as opposed to those that do not fly. The body mass distributions of three clades of small-bodied flying vertebrates show significant divergence from the distributions of their sister clades. We examined two alternative hypotheses for similarities among the size frequency distributions of the five clades. The hypothesis of functional symmetry corresponds to patterns of similarity expected if body mass distributions of flying clades are constrained by similar or identical functional limitations. The hypothesis of phylogenetic symmetry corresponds to patterns of similarity expected if body mass distributions reflect phylogenetic relationships among clades. -

1 Husbandry Guidelines Apodiformes Hummingbirds-Trochilidae Karen

Husbandry Guidelines Apodiformes Hummingbirds-Trochilidae Karen Krebbs, Conservation Biologist / Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum / Tucson, AZ Dave Rimlinger, Curator of Ornithology / San Diego Zoo / San Diego, CA Michael Mace, Curator of Ornithology / San Diego Wild Animal Park / Escondido, CA September, 2002 1. ACQUISITION AND ACCLIMATIZATION Sources of birds & acclimatization procedures - In the United States local species of hummingbirds can be collected with the proper permits. The Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum usually has species such as Anna's (Calypte anna), Costa's (Calypte costae), and Broad-billed (Cynanthus latirostris) for surplus each year if these species have nested in their Hummingbird Exhibit. In addition to keeping some native species, the San Diego Zoo has tried to maintain several exotic species such as Sparkling violet-ear (Colibri coruscans), Emerald (Amazilia amazilia), Oasis (Rhodopis vesper), etc. The San Diego Wild Animal Park has a large mixed species glass walk-through enclosure and has kept and produced hummingbirds over the years. All hummingbirds are on Appendix II of CITES and thus are covered under the Wild Bird Conservation Act (WBCA). An import permit from USFWS and an export permit from the country of origin must be obtained prior to the importation. Permits have been granted in the past, but currently it is difficult to find a country willing to export hummingbirds. Hummingbirds are more commonly kept in European collections, particularly private collections, and could be a source for future imports. Weighing Hummingbirds can be placed in a soft mesh bag and weighed with a spring scale. Electronic digital platform scales can also be used. A small wooden crate with a wire mesh front can also be used for weighing. -

Birds Checklist STEPPE BIRDS of CALATRAVA

www.naturaindomita.com BIRDS CHECKLIST C = Common R = Resident. All year round. Steppe Birds of Calatrava LC = Less Common S = Spring & Summer. Usually breeding. Calatrava Steppes and Guadiana Steppes R = Rare or Scarce W = Autumn & Winter M = Only on migration Familia Nombre Científico Inglés Español Frequency Season 1 Podicipedidae Podiceps nigricollis Black-Necked Grebe Zampullín Cuellinegro 2 Podicipedidae Tachybaptus ruficollis Little Grebe Zampullín Común 3 Podicipedidae Podiceps cristatus Great Crested Grebe Somormujo Lavanco 4 Phalacrocoracidae Phalacrocorax carbo Great Cormorant Cormorán Grande 5 Ardeidae Botaurus stellaris Great Bittern Avetoro 6 Ardeidae Ixobrychus minutus Little Bittern Avetorillo Común R S 7 Ardeidae Nycticorax nycticorax Black-Crowned Night Heron Martinete Común LC S 8 Ardeidae Bubulcus ibis Cattle Egret Garcilla Bueyera CR 9 Ardeidae Ardeola ralloides Squacco Heron Garcilla Cangrejera RS 10 Ardeidae Egretta garzetta Little Egret Garceta Común CR 11 Ardeidae Egretta alba Great Egret Garceta Grande LC R 12 Ardeidae Ardea cinerea Grey Heron Garza Real LC R 13 Ardeidae Ardea purpurea Purple Heron Garza Imperial RS 14 Ciconiidae Ciconia ciconia White Stork Cigüeña Blanca CR 15 Ciconiidae Ciconia nigra Black Stork Cigüeña Negra 16 Threskiornithidae Plegadis falcinellus Glossy Ibis Morito Común LC S 17 Threskiornithidae Platalea leucorodia Eurasian Spoonbill Espátula Común LC S 18 Phoenicopteridae Phoenicopterus ruber Greater Flamingo Flamenco Común 19 Anatidae Anser albifrons Greater White-Fronted Goose Ánsar -

Urbanisation and Nest Building in Birds Reynolds, Silas; Ibáñezálamo, Juan Diego; Sumasgutner, Petra; Mainwaring, Mark

University of Birmingham Urbanisation and nest building in birds Reynolds, Silas; IbáñezÁlamo, Juan Diego; Sumasgutner, Petra; Mainwaring, Mark DOI: 10.1007/s10336-019-01657-8 License: Creative Commons: Attribution (CC BY) Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Citation for published version (Harvard): Reynolds, S, IbáñezÁlamo, JD, Sumasgutner, P & Mainwaring, M 2019, 'Urbanisation and nest building in birds: a review of threats and opportunities', Journal of Ornithology, vol. 160, pp. 841-860. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10336-019-01657-8 Link to publication on Research at Birmingham portal General rights Unless a licence is specified above, all rights (including copyright and moral rights) in this document are retained by the authors and/or the copyright holders. The express permission of the copyright holder must be obtained for any use of this material other than for purposes permitted by law. •Users may freely distribute the URL that is used to identify this publication. •Users may download and/or print one copy of the publication from the University of Birmingham research portal for the purpose of private study or non-commercial research. •User may use extracts from the document in line with the concept of ‘fair dealing’ under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (?) •Users may not further distribute the material nor use it for the purposes of commercial gain. Where a licence is displayed above, please note the terms and conditions of the licence govern your use of this document. When citing, please reference the published version. Take down policy While the University of Birmingham exercises care and attention in making items available there are rare occasions when an item has been uploaded in error or has been deemed to be commercially or otherwise sensitive. -

CP Bird Collection

Lab Practical 2: Apodiformes - Passeriformes # = Male and Female * = Specimen out only once Timaliidae Emberizidae Apodiformes Wrentit Abert's Towhee Apodidae California Towhee White-throated Swift Paridae Mountain Chickadee Trochilidae Dark-eyed Junco Oak Titmouse # Anna's Hummingbird Golden-crowned Sparrow Aegithalidae Black-chinned Hummingbird Green-tailed Towhee Bushtit Calliope Hummingbird Lincoln's Sparrow Sittidae Costa's Hummingbird Sage Sparrow Pygmy Nuthatch Savannah Sparrow Coraciiformes White-breasted Nuthatch Spotted Towhee Alcedinidae Troglodytidae White-crowned Sparrow Belted Kingfisher Bewick's Wren Cardinalidae Piciformes Cactus Wren # Black-headed Grosbeak Picidae House Wren Blue Grosbeak Acorn Woodpecker Rock Wren Lazuli Bunting Downy Woodpecker Cinclidae # Western Tanager American Dipper Lewis's Woodpecker Icteridae Regulidae # Northern Flicker # Brewer's Blackbird # Ruby-crowned Kinglet Nuttall's Woodpecker # Brown-headed Cowbird Turdidae Red-breasted Sapsucker # Bullock's Oriole American Robin Red-naped Sapsucker # Hooded Oriole Hermit Thrush # Red-winged Blackbird Passeriformes Swainson's Thrush Tyrannidae Tricolored Blackbird # Western Bluebird Ash-throated Flycatcher Western Meadowlark Mimidae Black Phoebe # Yellow-headed Blackbird California Thrasher Cassin's Kingbird Fringillidae Crissal Thrasher Pacific-slope Flycatcher # Cassin's Finch Northern Mockingbird Say's Phoebe # House Finch Sturnidae Western Kingbird Lesser Goldfinch European Starling Pine Siskin Western Wood-Pewee Bombycillidae Passeridae Laniidae Cedar Waxwing # House Sparrow Loggerhead Shrike Ptilogonatidae Corvidae Phainopepla American Crow Parulidae Clark's Nutcracker Common Yellowthroat Mexican Jay MacGillivray's Warbler Steller's Jay Orange-crowned Warbler Western Scrub-Jay Townsend's Warbler Alaudidae Wilson's Warbler Horned Lark Yellow-breasted Chat Hirundinidae Yellow-rumped Warbler Cliff Swallow Tree Swallow Violet-green Swallow SKELETAL SYSTEM ANATOMY In this section you will utilize skeletons and disarticulated bones to identify internal structures. -

Weed Management Increases the Detrimental Effect of an Invasive

Biological Conservation 233 (2019) 93–101 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Biological Conservation journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/biocon Weed management increases the detrimental effect of an invasive parasite on arboreal Darwin's finches T Arno Cimadoma, Heinke Jägerb, Christian H. Schulzec, Rebecca Hood-Nowotnyd, ⁎ Christian Wappla, Sabine Tebbicha, a Department of Behavioural Biology, University of Vienna, 1090 Vienna, Austria b Charles Darwin Research Station, Charles Darwin Foundation, Santa Cruz Island, Galápagos, Ecuador c Department of Botany and Biodiversity Research, University of Vienna, 1030 Vienna, Austria d Institute of Soil Research, University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences, 1180 Vienna, Austria ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: The detrimental effects of invasive parasites on hosts often increase under poor environmental conditions. Both Philornis downsi natural fluctuations in environmental conditions and habitat management measures can temporarily cause Darwin's finches adverse environmental effects. In this study, we investigated the interaction between the invasive parasitic fly Invasive species Philornis downsi, control of invasive plants and precipitation on the breeding success of Darwin's finches. Parasitism Introduced plant species have invaded a unique forest on the Galapagos island of Santa Cruz, which is a key Arthropod biomass habitat for Darwin's finches. The Galapagos National Park Directorate applies manual control and herbicides to Weed management combat this invasion. We hypothesized that these measures led to a reduction in the arthropod food supply during chick rearing, which in turn caused mortality in chicks that were already weakened by parasitism. We compared food availability in three study sites of varying degrees of weed management. To assess the interaction of parasitism and weed management, we experimentally reduced P. -

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material Aleksi Lehikoinen*, Alison Johnston & Dario Massimino 2021: Climate and land use changes: similarity in range and abundance changes of birds in Finland and Great Britain and structure of a breeding. — Ornis Fennica 98: 1–15. A. Lehikoinen, The Helsinki Lab of Ornithology, Finnish Museum of Natural History, P.O. Box 17, Helsinki, Finland * Corresponding author’s e-mail: [email protected] A. Johnston, The Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Cornell University, 159 Sapsucker Woods Road, Ithaca, NY 14850, USA. Department of Zoology, Conservation Science Group, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK. The British Trust for Ornithology, The Nunnery, Thetford, Norfolk IP24 2PU, UK D. Massimino, The British Trust for Ornithology, The Nunnery, Thetford, Norfolk IP24 2PU, UK Supplementary Table 1. Annual rate of range size change and shift in mean weighted latitude of 56 species in Britain and Finland, that were used in distribution analyses. The main habitat type (Hab; F = forest, W = wetland, O = open), mean northerness in terms of latitude of distribution (Lat) as well as taxonomy (Genus, Family and Order) of species are given. Range change Distribution shift Species Hab Lat Genus Family Order Britain Finland Britain Finland Mute Swan Cygnus olor 1.002 1.038 0.828 2.536 W 0.271 Cygnus Anatidae Anseriformes Canada Goose Branta canadensis 1.024 1.155 2.482 3.781 W 0.244 Branta Anatidae Anseriformes Gadwall Anas strepera 1.039 1.105 –1.095 2.453 W 0.309 Mareca Anatidae Anseriformes Garganey Anas querquedula 1.01 0.997 2.91 -

2020 National Bird List

2020 NATIONAL BIRD LIST See General Rules, Eye Protection & other Policies on www.soinc.org as they apply to every event. Kingdom – ANIMALIA Great Blue Heron Ardea herodias ORDER: Charadriiformes Phylum – CHORDATA Snowy Egret Egretta thula Lapwings and Plovers (Charadriidae) Green Heron American Golden-Plover Subphylum – VERTEBRATA Black-crowned Night-heron Killdeer Charadrius vociferus Class - AVES Ibises and Spoonbills Oystercatchers (Haematopodidae) Family Group (Family Name) (Threskiornithidae) American Oystercatcher Common Name [Scientifc name Roseate Spoonbill Platalea ajaja Stilts and Avocets (Recurvirostridae) is in italics] Black-necked Stilt ORDER: Anseriformes ORDER: Suliformes American Avocet Recurvirostra Ducks, Geese, and Swans (Anatidae) Cormorants (Phalacrocoracidae) americana Black-bellied Whistling-duck Double-crested Cormorant Sandpipers, Phalaropes, and Allies Snow Goose Phalacrocorax auritus (Scolopacidae) Canada Goose Branta canadensis Darters (Anhingidae) Spotted Sandpiper Trumpeter Swan Anhinga Anhinga anhinga Ruddy Turnstone Wood Duck Aix sponsa Frigatebirds (Fregatidae) Dunlin Calidris alpina Mallard Anas platyrhynchos Magnifcent Frigatebird Wilson’s Snipe Northern Shoveler American Woodcock Scolopax minor Green-winged Teal ORDER: Ciconiiformes Gulls, Terns, and Skimmers (Laridae) Canvasback Deep-water Waders (Ciconiidae) Laughing Gull Hooded Merganser Wood Stork Ring-billed Gull Herring Gull Larus argentatus ORDER: Galliformes ORDER: Falconiformes Least Tern Sternula antillarum Partridges, Grouse, Turkeys, and