A High-Resolution Integrated Map of Copy Number Polymorphisms Within

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Single Cell Derived Clonal Analysis of Human Glioblastoma Links

SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: Single cell derived clonal analysis of human glioblastoma links functional and genomic heterogeneity ! Mona Meyer*, Jüri Reimand*, Xiaoyang Lan, Renee Head, Xueming Zhu, Michelle Kushida, Jane Bayani, Jessica C. Pressey, Anath Lionel, Ian D. Clarke, Michael Cusimano, Jeremy Squire, Stephen Scherer, Mark Bernstein, Melanie A. Woodin, Gary D. Bader**, and Peter B. Dirks**! ! * These authors contributed equally to this work.! ** Correspondence: [email protected] or [email protected]! ! Supplementary information - Meyer, Reimand et al. Supplementary methods" 4" Patient samples and fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS)! 4! Differentiation! 4! Immunocytochemistry and EdU Imaging! 4! Proliferation! 5! Western blotting ! 5! Temozolomide treatment! 5! NCI drug library screen! 6! Orthotopic injections! 6! Immunohistochemistry on tumor sections! 6! Promoter methylation of MGMT! 6! Fluorescence in situ Hybridization (FISH)! 7! SNP6 microarray analysis and genome segmentation! 7! Calling copy number alterations! 8! Mapping altered genome segments to genes! 8! Recurrently altered genes with clonal variability! 9! Global analyses of copy number alterations! 9! Phylogenetic analysis of copy number alterations! 10! Microarray analysis! 10! Gene expression differences of TMZ resistant and sensitive clones of GBM-482! 10! Reverse transcription-PCR analyses! 11! Tumor subtype analysis of TMZ-sensitive and resistant clones! 11! Pathway analysis of gene expression in the TMZ-sensitive clone of GBM-482! 11! Supplementary figures and tables" 13" "2 Supplementary information - Meyer, Reimand et al. Table S1: Individual clones from all patient tumors are tumorigenic. ! 14! Fig. S1: clonal tumorigenicity.! 15! Fig. S2: clonal heterogeneity of EGFR and PTEN expression.! 20! Fig. S3: clonal heterogeneity of proliferation.! 21! Fig. -

WO 2019/068007 Al Figure 2

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization I International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2019/068007 Al 04 April 2019 (04.04.2019) W 1P O PCT (51) International Patent Classification: (72) Inventors; and C12N 15/10 (2006.01) C07K 16/28 (2006.01) (71) Applicants: GROSS, Gideon [EVIL]; IE-1-5 Address C12N 5/10 (2006.0 1) C12Q 1/6809 (20 18.0 1) M.P. Korazim, 1292200 Moshav Almagor (IL). GIBSON, C07K 14/705 (2006.01) A61P 35/00 (2006.01) Will [US/US]; c/o ImmPACT-Bio Ltd., 2 Ilian Ramon St., C07K 14/725 (2006.01) P.O. Box 4044, 7403635 Ness Ziona (TL). DAHARY, Dvir [EilL]; c/o ImmPACT-Bio Ltd., 2 Ilian Ramon St., P.O. (21) International Application Number: Box 4044, 7403635 Ness Ziona (IL). BEIMAN, Merav PCT/US2018/053583 [EilL]; c/o ImmPACT-Bio Ltd., 2 Ilian Ramon St., P.O. (22) International Filing Date: Box 4044, 7403635 Ness Ziona (E.). 28 September 2018 (28.09.2018) (74) Agent: MACDOUGALL, Christina, A. et al; Morgan, (25) Filing Language: English Lewis & Bockius LLP, One Market, Spear Tower, SanFran- cisco, CA 94105 (US). (26) Publication Language: English (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every (30) Priority Data: kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, 62/564,454 28 September 2017 (28.09.2017) US AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BN, BR, BW, BY, BZ, 62/649,429 28 March 2018 (28.03.2018) US CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DJ, DK, DM, DO, (71) Applicant: IMMP ACT-BIO LTD. -

Genome-Wide Screening Identifies Genes and Biological Processes

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 10-12-2018 Genome-Wide Screening Identifies Genes and Biological Processes Implicated in Chemoresistance and Oncogene-Induced Apoptosis Tengyu Ko Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Cancer Biology Commons, Cell Biology Commons, and the Genomics Commons Recommended Citation Ko, Tengyu, "Genome-Wide Screening Identifies Genes and Biological Processes Implicated in Chemoresistance and Oncogene- Induced Apoptosis" (2018). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 4715. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/4715 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. GENOME-WIDE SCREENING IDENTIFIES GENES AND BIOLOGICAL PROCESSES IMPLICATED IN CHEMORESISTANCE AND ONCOGENE- INDUCED APOPTOSIS A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Biomedical and Veterinary Medical Sciences through the Department of Comparative Biomedical Sciences by Tengyu Ko B.S., University of California, Santa Barbara 2010 December 2018 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my sincerest gratitude to my major supervisor Dr. Shisheng Li for giving me the opportunity to join his team and the freedom to pursue projects. I appreciate all of his thoughts and efforts. Truly, none of these findings would be possible without his supervisions, supports, insightful discussions, and patience. -

Gene and Protein Networks in Understanding Cellular Function

Gene and Protein Networks in Understanding Cellular Function Sonja Katriina Lehtinen A thesis sumbitted to University College London for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 2015 1 I, Sonja Lehtinen, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Sonja Lehtinen 2 March, 2015 2 Abstract Over the past decades, networks have emerged as a useful way of representing complex large-scale systems in a variety of fields. In cellular and molecular biology, gene and protein networks have attracted considerable interest as tools for making sense of increasingly large volumes of data. Despite this interest, there is still substantial debate over how to best exploit network models in cellular biology. This thesis explores the use of gene and protein networks in various biological contexts. The first part of the thesis (Chapter 2) examines protein function prediction using network-based `guilt-by-association' approaches. Given the falling costs of genome sequencing and the availability of large volumes of biological data, automated annotation of gene and protein function is becoming increasingly useful. Chapter 2 describes the development of a new network-based protein function prediction method and compares it to a leading algorithm on a number of benchmarks. Biases in benchmarking methods are also explicitly explored. The second part (Chapters 3 and 4) explores network approaches in under- standing loss of function variation in the human genome. For a number of genes, homozygous loss of function appears to have no detrimental effect. -

Supplementary Data

SUPPLEMENTARY METHODS 1) Characterisation of OCCC cell line gene expression profiles using Prediction Analysis for Microarrays (PAM) The ovarian cancer dataset from Hendrix et al (25) was used to predict the phenotypes of the cell lines used in this study. Hendrix et al (25) analysed a series of 103 ovarian samples using the Affymetrix U133A array platform (GEO: GSE6008). This dataset comprises clear cell (n=8), endometrioid (n=37), mucinous (n=13) and serous epithelial (n=41) primary ovarian carcinomas and samples from 4 normal ovaries. To build the predictor, the Prediction Analysis of Microarrays (PAM) package in R environment was employed (http://rss.acs.unt.edu/Rdoc/library/pamr/html/00Index.html). When more than one probe described the expression of a given gene, we used the probe with the highest median absolute deviation across the samples. The dataset from Hendrix et al. (25) and the dataset of OCCC cell lines described in this manuscript were then overlaid on the basis of 11536 common unique HGNC gene symbols. Only the 99 primary ovarian cancers samples and the four normal ovary samples were used to build the predictor. Following leave one out cross-validation, a predictor based upon 126 genes was able to identify correctly the four distinct phenotypes of primary ovarian tumour samples with a misclassification rate of 18.3%. This predictor was subsequently applied to the expression data from the 12 OCCC cell lines to determine the likeliest phenotype of the OCCC cell lines compared to primary ovarian cancers. Posterior probabilities were estimated for each cell line in comparison to the following phenotypes: clear cell, endometrioid, mucinous and serous epithelial. -

Us 2018 / 0305689 A1

US 20180305689A1 ( 19 ) United States (12 ) Patent Application Publication ( 10) Pub . No. : US 2018 /0305689 A1 Sætrom et al. ( 43 ) Pub . Date: Oct. 25 , 2018 ( 54 ) SARNA COMPOSITIONS AND METHODS OF plication No . 62 /150 , 895 , filed on Apr. 22 , 2015 , USE provisional application No . 62/ 150 ,904 , filed on Apr. 22 , 2015 , provisional application No. 62 / 150 , 908 , (71 ) Applicant: MINA THERAPEUTICS LIMITED , filed on Apr. 22 , 2015 , provisional application No. LONDON (GB ) 62 / 150 , 900 , filed on Apr. 22 , 2015 . (72 ) Inventors : Pål Sætrom , Trondheim (NO ) ; Endre Publication Classification Bakken Stovner , Trondheim (NO ) (51 ) Int . CI. C12N 15 / 113 (2006 .01 ) (21 ) Appl. No. : 15 /568 , 046 (52 ) U . S . CI. (22 ) PCT Filed : Apr. 21 , 2016 CPC .. .. .. C12N 15 / 113 ( 2013 .01 ) ; C12N 2310 / 34 ( 2013. 01 ) ; C12N 2310 /14 (2013 . 01 ) ; C12N ( 86 ) PCT No .: PCT/ GB2016 /051116 2310 / 11 (2013 .01 ) $ 371 ( c ) ( 1 ) , ( 2 ) Date : Oct . 20 , 2017 (57 ) ABSTRACT The invention relates to oligonucleotides , e . g . , saRNAS Related U . S . Application Data useful in upregulating the expression of a target gene and (60 ) Provisional application No . 62 / 150 ,892 , filed on Apr. therapeutic compositions comprising such oligonucleotides . 22 , 2015 , provisional application No . 62 / 150 ,893 , Methods of using the oligonucleotides and the therapeutic filed on Apr. 22 , 2015 , provisional application No . compositions are also provided . 62 / 150 ,897 , filed on Apr. 22 , 2015 , provisional ap Specification includes a Sequence Listing . SARNA sense strand (Fessenger 3 ' SARNA antisense strand (Guide ) Mathew, Si Target antisense RNA transcript, e . g . NAT Target Coding strand Gene Transcription start site ( T55 ) TY{ { ? ? Targeted Target transcript , e . -

ARTICLE Extensive Copy-Number Variation of the Human Olfactory Receptor Gene Family

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector ARTICLE Extensive Copy-Number Variation of the Human Olfactory Receptor Gene Family Janet M. Young,1 RaeLynn M. Endicott,1 Sean S. Parghi,1 Megan Walker,1 Jeffrey M. Kidd,1,2 and Barbara J. Trask1,* As much as a quarter of the human genome has been reported to vary in copy number between individuals, including regions containing about half of the members of the olfactory receptor (OR) gene family. We have undertaken a detailed study of copy-number variation of ORs to elucidate the selective and mechanistic forces acting on this gene family and the true impact of copy-number variation on human OR repertoires. We argue that the properties of copy-number variants (CNVs) and other sets of large genomic regions violate the assump- tions of statistical methods that are commonly used in the assessment of gene enrichment. Using more appropriate methods, we provide evidence that OR enrichment in CNVs is not due to positive selection but is because of OR preponderance in segmentally duplicated regions, which are known to be frequently copy-number variable, and because purifying selection against CNVs is lower in OR-contain- ing regions than in regions containing essential genes. We also combine multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA) and PCR to assay the copy numbers of 37 candidate CNV ORs in a panel of ~50 human individuals. We confirm copy-number variation of 18 ORs but find no variation in this human-diversity panel for 16 other ORs, highlighting the caveat that reported intervals often overre- present true CNVs. -

Explorations in Olfactory Receptor Structure and Function by Jianghai

Explorations in Olfactory Receptor Structure and Function by Jianghai Ho Department of Neurobiology Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Hiroaki Matsunami, Supervisor ___________________________ Jorg Grandl, Chair ___________________________ Marc Caron ___________________________ Sid Simon ___________________________ [Committee Member Name] Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Neurobiology in the Graduate School of Duke University 2014 ABSTRACT Explorations in Olfactory Receptor Structure and Function by Jianghai Ho Department of Neurobiology Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Hiroaki Matsunami, Supervisor ___________________________ Jorg Grandl, Chair ___________________________ Marc Caron ___________________________ Sid Simon ___________________________ [Committee Member Name] An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Neurobiology in the Graduate School of Duke University 2014 Copyright by Jianghai Ho 2014 Abstract Olfaction is one of the most primitive of our senses, and the olfactory receptors that mediate this very important chemical sense comprise the largest family of genes in the mammalian genome. It is therefore surprising that we understand so little of how olfactory receptors work. In particular we have a poor idea of what chemicals are detected by most of the olfactory receptors in the genome, and for those receptors which we have paired with ligands, we know relatively little about how the structure of these ligands can either activate or inhibit the activation of these receptors. Furthermore the large repertoire of olfactory receptors, which belong to the G protein coupled receptor (GPCR) superfamily, can serve as a model to contribute to our broader understanding of GPCR-ligand binding, especially since GPCRs are important pharmaceutical targets. -

Supplementary Tables

Supplementary Tables Supplementary Table 1. Differentially methylated genes in correlation with their expression pattern in the A4 progression model A. Hypomethylated–upregulated Genes (n= 76) ALOX5 RRAD RTN4R DSCR6 FGFR3 HTR7 WNT3A POGK PLCD3 ALPPL2 RTEL1 SEMA3B DUSP5 FOSB ITGB4 MEST PPL PSMB8 ARHGEF4 BST2 SEMA7A SLC12A7 FOXQ1 KCTD12 LETM2 PRPH PXMP2 ARNTL2 CDH3 SHC2 SLC20A2 HSPA2 KIAA0182 LIMK2 NAB1 RASIP1 ASRGL1 CLDN3 DCBLD1 SNX10 SSH1 KREMEN2 LIPE NDRG2 ATF3 CLU DCHS1 SOD3 ST3GAL4 MAL LRRC1 NR3C2 ATP8B3 CYC1 DGCR8 EBAG9 SYNGR1 TYMS MCM2 NRG2 RHOF DAGLA DISP2 FAM19A5 TNNI3 UNC5B MYB PAK6 RIPK4 DAZAP1 DOCK3 FBXO6 HSPA4L WHSC1 PNMT PCDH1 B. Hypermethylated-downregulated Genes (n= 31) ARHGAP22 TNFSF9 KLF6 LRP8 NRP1 PAPSS2 SLC43A2 TBC1D16 ASB2 DZIP1 TPM1 MDGA1 NRP2 PIK3CD SMARCA2 TLL2 C18orf1 FBN1 LHFPL2 TRIO NTNG2 PTGIS SOCS2 TNFAIP8 DIXDC1 KIFC3 LMO1 NR3C1 ODZ3 PTPRM SYNPO Supplementary Table 2. Genes enriched for different histone methylation marks in A4 progression model identified through ChIP-on-chip a. H3K4me3 (n= 978) AATF C20orf149 CUL3 FOXP1 KATNA1 NEGR1 RAN SPIN2B ABCA7 C20orf52 CWF19L1 FRK KBTBD10 NEIL1 RANBP2 SPPL2A ABCC9 C21orf13-SH3BGR CXCL3 FSIP1 KBTBD6 NELF RAPGEF3 SPRY4 ABCG2 C21orf45 CYC1 FUK KCMF1 NFKB2 RARB SPRYD3 ABHD7 C22orf32 CYorf15A FXR2 KCNH7 NGDN RASAL2 SPTLC2 ACA15 C2orf18 DAXX FZD9 KCNMB4 NKAP RASD1 SRFBP1 ACA26 C2orf29 DAZ3 G6PD KCTD18 NKTR RASEF SRI ACA3 C2orf32 DBF4 GABPB2 KDELR2 NNT RASGRF1 SRM ACA48 C2orf55 DBF4B GABRA5 KIAA0100 NOL5A RASSF1 SSH2 ACAT1 C3orf44 DBI GADD45B KIAA0226 NOLC1 RASSF3 SSH3 ACSL5 -

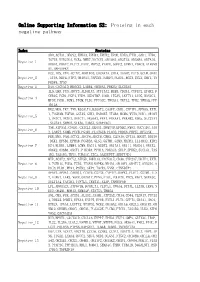

Online Supporting Information S2: Proteins in Each Negative Pathway

Online Supporting Information S2: Proteins in each negative pathway Index Proteins ADO,ACTA1,DEGS2,EPHA3,EPHB4,EPHX2,EPOR,EREG,FTH1,GAD1,HTR6, IGF1R,KIR2DL4,NCR3,NME7,NOTCH1,OR10S1,OR2T33,OR56B4,OR7A10, Negative_1 OR8G1,PDGFC,PLCZ1,PROC,PRPS2,PTAFR,SGPP2,STMN1,VDAC3,ATP6V0 A1,MAPKAPK2 DCC,IDS,VTN,ACTN2,AKR1B10,CACNA1A,CHIA,DAAM2,FUT5,GCLM,GNAZ Negative_2 ,ITPA,NEU4,NTF3,OR10A3,PAPSS1,PARD3,PLOD1,RGS3,SCLY,SHC1,TN FRSF4,TP53 Negative_3 DAO,CACNA1D,HMGCS2,LAMB4,OR56A3,PRKCQ,SLC25A5 IL5,LHB,PGD,ADCY3,ALDH1A3,ATP13A2,BUB3,CD244,CYFIP2,EPHX2,F CER1G,FGD1,FGF4,FZD9,HSD17B7,IL6R,ITGAV,LEFTY1,LIPG,MAN1C1, Negative_4 MPDZ,PGM1,PGM3,PIGM,PLD1,PPP3CC,TBXAS1,TKTL2,TPH2,YWHAQ,PPP 1R12A HK2,MOS,TKT,TNN,B3GALT4,B3GAT3,CASP7,CDH1,CYFIP1,EFNA5,EXTL 1,FCGR3B,FGF20,GSTA5,GUK1,HSD3B7,ITGB4,MCM6,MYH3,NOD1,OR10H Negative_5 1,OR1C1,OR1E1,OR4C11,OR56A3,PPA1,PRKAA1,PRKAB2,RDH5,SLC27A1 ,SLC2A4,SMPD2,STK36,THBS1,SERPINC1 TNR,ATP5A1,CNGB1,CX3CL1,DEGS1,DNMT3B,EFNB2,FMO2,GUCY1B3,JAG Negative_6 2,LARS2,NUMB,PCCB,PGAM1,PLA2G1B,PLOD2,PRDX6,PRPS1,RFXANK FER,MVD,PAH,ACTC1,ADCY4,ADCY8,CBR3,CLDN16,CPT1A,DDOST,DDX56 ,DKK1,EFNB1,EPHA8,FCGR3A,GLS2,GSTM1,GZMB,HADHA,IL13RA2,KIR2 Negative_7 DS4,KLRK1,LAMB4,LGMN,MAGI1,NUDT2,OR13A1,OR1I1,OR4D11,OR4X2, OR6K2,OR8B4,OXCT1,PIK3R4,PPM1A,PRKAG3,SELP,SPHK2,SUCLG1,TAS 1R2,TAS1R3,THY1,TUBA1C,ZIC2,AASDHPPT,SERPIND1 MTR,ACAT2,ADCY2,ATP5D,BMPR1A,CACNA1E,CD38,CYP2A7,DDIT4,EXTL Negative_8 1,FCER1G,FGD3,FZD5,ITGAM,MAPK8,NR4A1,OR10V1,OR4F17,OR52D1,O R8J3,PLD1,PPA1,PSEN2,SKP1,TACR3,VNN1,CTNNBIP1 APAF1,APOA1,CARD11,CCDC6,CSF3R,CYP4F2,DAPK1,FLOT1,GSTM1,IL2 -

Molecular Mechanism of Parosmia

medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.02.05.21251085; this version posted February 8, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under a CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license . 1 Molecular Mechanism of Parosmia 2 3 Jane K. Parker1, Christine E. Kelly2, Simon B. Gane3 4 5 6 1Department of Food and Nutritional Sciences, University of Reading, Whiteknights, Reading, UK 7 2AbScent, 14 London Road, Andover, Hampshire, UK 8 3Royal National Ear, Nose and Throat and Eastman Dental Hospitals, University College London 9 Hospital, UK. 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Corresponding author: S. Gane, Royal National Ear, Nose and Throat and Eastman Dental Hospitals, 21 University College London Hospital, UK. E-mail: [email protected] 22 NOTE: This preprint reports new research that has not been certified by peer review and should not be used to guide clinical practice. 1 medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.02.05.21251085; this version posted February 8, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under a CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license . 23 Abstract 24 The molecular stimuli that trigger a parosmic response have been identified. Parosmia is a debilitating 25 disease in which familiar smells become distorted and unpleasant. -

Genetic Analysis of Very Obese Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/185900; this version posted September 12, 2017. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Genetic analysis of very obese children with autism spectrum disorder Herman D. Cortes and Rachel Wevrick* Dept. of Medical Genetics, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta Canada *Corresponding author. Authors: Rachel Wevrick, Dept. of Medical Genetics, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta Canada, [email protected] Herman D. Cortes, Dept. of Medical Genetics, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta Canada, [email protected] Running title: Syndromic autism with obesity in the SSC Key words: SSC, autism spectrum disorder, obesity, Wnt, Gene Ontology 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/185900; this version posted September 12, 2017. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Abstract: Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is defined by the triad of deficits in social interactions, deficits in communication, and repetitive behaviors. Common co-morbidities in syndromic forms of ASD include intellectual disability, seizures, and obesity. We asked whether very obese children with ASD had different behavioral, physical and genetic characteristics compared to children with ASD who were not obese. We found that very obese children with ASD had significantly poorer scores on standardized behavioral tests.