Mobile Phone Manufacturing in China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

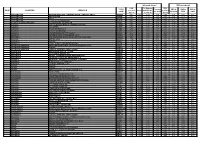

ZONE COUNTRIES OPERATOR TADIG CODE Calls

Calls made abroad SMS sent abroad Calls To Belgium SMS TADIG To zones SMS to SMS to SMS to ZONE COUNTRIES OPERATOR received Local and Europe received CODE 2,3 and 4 Belgium EUR ROW abroad (= zone1) abroad 3 AFGHANISTAN AFGHAN WIRELESS COMMUNICATION COMPANY 'AWCC' AFGAW 0,91 0,99 2,27 2,89 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 3 AFGHANISTAN AREEBA MTN AFGAR 0,91 0,99 2,27 2,89 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 3 AFGHANISTAN TDCA AFGTD 0,91 0,99 2,27 2,89 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 3 AFGHANISTAN ETISALAT AFGHANISTAN AFGEA 0,91 0,99 2,27 2,89 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 1 ALANDS ISLANDS (FINLAND) ALANDS MOBILTELEFON AB FINAM 0,08 0,29 0,29 2,07 0,00 0,09 0,09 0,54 2 ALBANIA AMC (ALBANIAN MOBILE COMMUNICATIONS) ALBAM 0,74 0,91 1,65 2,27 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 2 ALBANIA VODAFONE ALBVF 0,74 0,91 1,65 2,27 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 2 ALBANIA EAGLE MOBILE SH.A ALBEM 0,74 0,91 1,65 2,27 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 2 ALGERIA DJEZZY (ORASCOM) DZAOT 0,74 0,91 1,65 2,27 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 2 ALGERIA ATM (MOBILIS) (EX-PTT Algeria) DZAA1 0,74 0,91 1,65 2,27 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 2 ALGERIA WATANIYA TELECOM ALGERIE S.P.A. -

Taiwan's Top 50 Corporates

Title Page 1 TAIWAN RATINGS CORP. | TAIWAN'S TOP 50 CORPORATES We provide: A variety of Chinese and English rating credit Our address: https://rrs.taiwanratings.com.tw rating information. Real-time credit rating news. Credit rating results and credit reports on rated corporations and financial institutions. Commentaries and house views on various industrial sectors. Rating definitions and criteria. Rating performance and default information. S&P commentaries on the Greater China region. Multi-media broadcast services. Topics and content from Investor outreach meetings. RRS contains comprehensive research and analysis on both local and international corporations as well as the markets in which they operate. The site has significant reference value for market practitioners and academic institutions who wish to have an insight on the default probability of Taiwanese corporations. (as of June 30, 2015) Chinese English Rating News 3,440 3,406 Rating Reports 2,006 2,145 TRC Local Analysis 462 458 S&P Greater China Region Analysis 76 77 Contact Us Iris Chu; (886) 2 8722-5870; [email protected] TAIWAN RATINGS CORP. | TAIWAN'S TOP 50 CORPORATESJenny Wu (886) 2 872-5873; [email protected] We warmly welcome you to our latest study of Taiwan's top 50 corporates, covering the island's largest corporations by revenue in 2014. Our survey of Taiwan's top corporates includes an assessment of the 14 industry sectors in which these companies operate, to inform our views on which sectors are most vulnerable to the current global (especially for China) economic environment, as well as the rising strength of China's domestic supply chain. -

Gomo Troubleshoot

GOMO Travel SIM Frequently Asked Questions 1. What is GOMO Travel SIM? GOMO Travel SIM is a prepaid, data-only SIM Card for travellers heading to Malaysia, Australia, Thailand, Philippines, Indonesia, Hong Kong, Macau, Taiwan, South Korea and Japan. FYI, this is a data-only SIM, so no talk time/SMS is included. We suggest using your favourite chat or social apps. 2. How do I activate my data after getting my GOMO Travel SIM? Simple! Just head over to gomo.sg/activate and choose your desired travel start date. It only takes minutes to complete! 3. How can I check the data balance and expiry date of my GOMO Travel SIM? Check your data balance and expiry date at gomo.sg/manage. 4. Can I share the data with my friends? Yes, you can tether the data with a mobile phone or WIFI dongle. 5. How long is the data valid for in my GOMO Travel SIM? You can use it for 10 days from your desired travel start date. 6. Can I top up the data in my GOMO Travel SIM? There is no top up option available. You can’t since each GOMO Travel SIM is valid for 10 days only. 7. I have previously purchased a GOMO Travel SIM. Is it still valid? Yes! Your 3GB travel SIM is still valid for use till 12 June 2020, while your 2GB travel SIM is valid till 21 Feb 2021. 8. I can’t connect to data after landing, please help! Please refer to our troubleshooting guide below. -

Ctbc Financial Holding Co., Ltd. and Subsidiaries

1 Stock Code:2891 CTBC FINANCIAL HOLDING CO., LTD. AND SUBSIDIARIES Consolidated Financial Statements With Independent Auditors’ Report For the Six Months Ended June 30, 2019 and 2018 Address: 27F and 29F, No.168, Jingmao 2nd Rd., Nangang Dist., Taipei City 115, Taiwan, R.O.C. Telephone: 886-2-3327-7777 The independent auditors’ report and the accompanying consolidated financial statements are the English translation of the Chinese version prepared and used in the Republic of China. If there is any conflict between, or any difference in the interpretation of the English and Chinese language independent auditors’ report and consolidated financial statements, the Chinese version shall prevail. 2 Table of contents Contents Page 1. Cover Page 1 2. Table of Contents 2 3. Independent Auditors’ Report 3 4. Consolidated Balance Sheets 4 5. Consolidated Statements of Comprehensive Income 5 6. Consolidated Statements of Changes in Stockholder’s Equity 6 7. Consolidated Statements of Cash Flows 7 8. Notes to the Consolidated Financial Statements (1) History and Organization 8 (2) Approval Date and Procedures of the Consolidated Financial Statements 8 (3) New Standards, Amendments and Interpretations adopted 9~12 (4) Summary of Significant Accounting Policies 12~39 (5) Primary Sources of Significant Accounting Judgments, Estimates and 40 Assumptions Uncertainty (6) Summary of Major Accounts 40~202 (7) Related-Party Transactions 203~215 (8) Pledged Assets 216 (9) Significant Contingent Liabilities and Unrecognized Contract 217~226 Commitment (10) Significant Catastrophic Losses 227 (11) Significant Subsequent Events 227 (12) Other 227~282 (13) Disclosures Required (a) Related information on significant transactions 283~287 (b) Related information on reinvestment 287~289 (c) Information on investment in Mainland China 289~290 (14) Segment Information 291 KPMG 11049 5 7 68 ( 101 ) Telephone + 886 (2) 8101 6666 台北市 信義路 段 號 樓 台北 大樓 68F., TAIPEI 101 TOWER, No. -

Deloitte Football Money League 2009

Lost in translation Football Money League Sports Business Group February 2009 The unique nature of the football industry will enable major clubs to be relatively resistant to the economic downturn Contents 2 Welcome 5 How we did it 6 Ups and downs 7 The Deloitte Football Money League 28 Tackling the crunch Edited by Dan Jones Authors Austin Houlihan, Rich Parkes, Martyn Hawkins, Simon Hearne, Amelia Ashton-Jones and Caspar Schmick Sports Business Group at Deloitte PO Box 500, 2 Hardman Street, Manchester, UK M60 2AT Telephone: +44 (0)161 455 8787 Fax: +44 (0)161 455 6013 E-mail: [email protected] www.deloitte.co.uk/sportsbusinessgroup February 2009 Football Money League 2009 Sports Business Group 1 Welcome Welcome to the twelfth edition of the Deloitte Football Chart 1: Total revenues 2007/08 (€m) Money League, in which we profile the largest clubs in the world’s most popular sport. Being released less than 400 nine months after the end of the 2007/08 season, and 8 as soon as all the clubs’ revenue figures are available to . 350 5 6 us, the Money League is the most contemporary and 3 8 . reliable analysis of clubs’ relative financial performance. 4 2 300 8 . 3 8 3 . 0 5 3 There are a number of methods that can be used to 9 2 9 . 4 . 250 8 e l determine the size of a club including measures of 4 r 6 l i 6 u 2 e 2 p s s r fanbase, attendance, broadcast audience, or on-pitch t a o d e M H t 9 i V success. -

“Hi!Dataroam” Refers to the Various Singtel Mobile Prepaid Data Roam Plans Described in Clause 2 Below

hi!DataRoam Specific Terms & Conditions 1. Definitions “hi!DataRoam” refers to the various Singtel Mobile Prepaid Data Roam Plans described in clause 2 below. “General Terms” refers to Singapore Telecommunications Limited's General Terms and Conditions of Service found at www.singtel.com/prepaid. “Main Account” refers to the User’s charging account for the purchase of hi!DataRoam plans. “Specific Terms” refers to Singapore Telecommunications Limited’s Specific Terms and Conditions of Service. “Singtel Mobile” refers to Singtel Mobile Singapore Pte Ltd (CRN: 201012456C). “User” refers to the Customer of SingTel who is the registered owner of the Singtel Mobile Prepaid line. Words and expressions used in this hi!DataRoam special Terms and Conditions shall have the same meaning as defined in the General Terms and/or the Specific Terms unless the context otherwise requires. The headings or titles to the clauses in this hi!DataRoam special Terms and Conditions are for reference only and shall not be referred to or relied upon in the construction of any provision of these hi!DataRoam Plans Terms and Conditions. 2. Purchase of hi!DataRoam Plans 2.1 The hi!DataRoam plan comprises 100MB of data to be used whilst roaming in the following countries and with the preferred operators. Country Preferred Operator Handset Display Malaysia Maxis My Maxis / My 012/50 212 Indonesia Telkomsel TELKOMSEL / IND TELKOMSEL / TSEL China China Mobile CHINA MOBILE / CMCC China Unicom China Unicom / CHN CUGSM / CUGSM Hong Kong CSL HK CSL India Bharti AirTel / IND Airtel / INA AIRTEL Thailand AIS AIS / 520 03 / TH GSM / TH AIS / TH AIS GSM Philippines Globe Telecom GLOBE PH / GLOBE Australia Optus YES OPTUS TAIWAN MOBILE / TW MOBILE / TWN GSM / Taiwan Taiwan Mobile PACIFIC / TWN GSM1800 / TWN97 / ROC 97 / 466 97 / TW 97 / TCC Japan Softbank Mobile J-Phone / Vodafone JP / 44020 / SOFTBANK South Korea SK Telecom SK TELECOM / KOR SK Telecom / 450 05 2.2 User will be able to purchase the plan within Singapore or at Country of destination included in the above plan by calling *100#. -

TAICS 2018 Annual Report

2018 Annual Report Taiwan Association of Information and Communication Standards 1 Annual Event 03/09 Technical Management Technical Meeting Committee Meeting #6.1 Standard Counsel Committee 03/09 Meeting #6 03/13 The Sixth Meetings Activity of the First Board of Supervisors Seminar 5G Standardization Lecture ~ Workshop 05/18 The trend of 3GPP 5G NR 2nd TAICS-ARIB Joint 5G Standardization Smart Mobile Application 05/25 and Services Workshop 05/30 Technical Management Committee Meeting #7 06/11 Forum 2018 TAICS Standardation 2018 Public Meeting: Security Certification & Verification 06/26 Forum: Battery Management Procedure of IoT Devices and Service Development 06/26 Trends of Electric Vehicles The 1st General Meeting of Activity Second General Assembly & 07/10 The 1st Meetings of the The Signing Ceremony Second Board of Supervisors Annual 07/26 5G NR Lecture-1 Seminar Indusrial Exporter Forum of 08/01 The NFC Test Specification of Readers and Mobile Phones 08/02 5G NR Lecture-2 Report Technical Management 08/03 Committee Meeting #7 Technical Meeting 08/31 5G Millimeter Wave Lecture The Latest International Technical Management 09/18 10/04 Standardation Sharing - 5G & IoV Committee Meeting #7.2 2018 TAICS Global Standards 10/16 Forum - Cybersecurity–Privacy Workshop Protection in IoT-era The 2nd Meetings of the Second Board 11/02 10/30 TSDSI-TAICS 5G Workshop of Supervisors Activity TC Plenary Meeting#6 11/30 Technical Meeting IoT Security Mark 12/12 Launching Ceremony Taiwan Association of Information and Communication Standards Forum -

40% More Gigabytes in Spite of the Pandemic

Industry analysis #3 2020 Mobile data – first half 2020 40% more gigabytes in spite of the pandemic But revenue negatively affected: -0.5% 140% Average +51% Average +54% th 120% Tefficient’s 28 public analysis on the 100% development and drivers of mobile data ranks 116 80% operators based on average data usage per 60% SIM, total data traffic and revenue per gigabyte in 40% the first half of 2020. y growth in mobile data usage data mobile in y growth - o - 20% Y The data usage per SIM grew for basically every 0% Q1 2020 Q2 2020 operator. 42% could turn -20% that data usage growth into ARPU growth. It’s a bit lower than in our previous reports and COVID-19 is to blame; many operators did report negative revenue development in Q2 2020 when travelling stopped and many prepaid subscriptions expired. Mobile data traffic continued to grow, though: +40%. Although operators in certain markets were giving mobile data away to mitigate the negative consequences of lockdowns, most of the global traffic growth is true, underlying, growth. Data usage actually grew faster in Q2 2020 than in Q1 2020 even though lockdowns mainly affected Q2. Our industry demonstrated resilience, but now needs to fill the data monetisation toolbox with more or sharper tools. tefficient AB www.tefficient.com 3 September 2020 1 27 operators above 10 GB per SIM per month in 1H 2020 Figure 1 shows the average mobile data usage for 116 reporting or reported1 mobile operators globally with values for the first half of 2020 or the full year of 2019. -

Roaming User Guide

Data Roaming Tips Singtel helps you stay seamlessly connected with data roaming overseas while avoiding bill shock from unexpected roaming charges. The information below can help you make smart data roaming decisions, allowing you to enjoy your trip with peace of mind. 1. Preferred Network Operators and LTE Roaming ...................................................................................... 2 2. USA Data Roaming Plan Coverage .......................................................................................................... 13 3. Network Lock .............................................................................................................................................. 14 4. My Roaming Settings................................................................................................................................. 16 5. Data Roaming User Guide ......................................................................................................................... 16 1. Preferred Network Operators and LTE Roaming The following table lists our preferred operators offering Singtel data roaming plans and indicates their handset display names. Country Roaming Plans Operator Handset Display Albania Daily Vodafone (LTE) VODAFONE AL / voda AL / AL-02 / 276-02 Anguilla Daily Cable & Wireless C&W / 365 840 Antigua and Daily Cable & Wireless C&W / 344 920 Barbuda CLARO Argentina / CTIARG / AR310 / Claro (LTE) Claro AR Argentina Daily Telefonica (LTE) AR 07 / 722 07 / unifon / movistar Armenia Daily VEON (LTE) -

Post-Paid Autoroamtm

Post-Paid AutoroaMtM Using yoUr Post-Paid Mobile overseas Optus AutoRoam™ lets you stay in touch while you’re travelling through some of the most popular overseas destinations. Post-Paid autoroam™ gives you these great benefits: • Stay in touch with your family and friends even when you are on holidays, day or night. • There’s no need for expensive hotel phones or the inconvenience of public phones. • Your mobile number doesn’t change, which means your contacts can call you without having to remember another number. • Callers in Australia are only charged for a national call to you while you are overseas. • Depending on your overseas carrier, you can screen your incoming calls and divert those you don’t want to answer to voicemail.# as an optus Post-Paid customer, you can: • SMS ‘A’ to 321 and VoiceMail will call you back (standard roaming charges apply)~ or • Access VoiceMail by calling +61 4 1100 0321 (standard roaming charges apply) • For general or billing enquiries while overseas, please call Optus Customer Care on +61 2 8082 5678. (50¢ per call). Optus Customer Care is open from 8am – 7pm (AEST) Mon to Fri and 9am – 5pm (AEST) on Saturdays. • And for faults with your mobile phone, you can call +61 2 8082 2642 for assistance. The Mobile Technical Support Centre is open 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. For your convenience, all your overseas charges are billed back to your Optus account in Australian dollars. ConvenienCe of data roaMing While the ability to use your regular data services overseas is convenient, it’s good to know how data is charged when roaming. -

Case No COMP/M.3911 - BENQ / SIEMENS MOBILE

EN Case No COMP/M.3911 - BENQ / SIEMENS MOBILE Only the English text is available and authentic. REGULATION (EC) No 139/2004 MERGER PROCEDURE Article 6(1)(b) NON-OPPOSITION Date: 07/09/2005 In electronic form on the EUR-Lex website under document number 32005M3911 Office for Official Publications of the European Communities L-2985 Luxembourg COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES Brussels, 07-IX-2005 SG-Greffe(2005) D/204914 PUBLIC VERSION MERGER PROCEDURE ARTICLE 6(1)(b) DECISION To the notifying party Dear Sir/Madam, Subject: Case No COMP/M.3911 –BenQ / Siemens Mobile Notification of 04/08/05 pursuant to Article 4 of Council Regulation No 139/20041 1. On the 4 August 2005, the Commission received a notification of a proposed concentration pursuant to Article 4 of Council Regulation (EC) No 139/2004 by which the undertaking BenQ Corporation (“BenQ”, Taiwan, Republic of China) acquires, within the meaning of 3(1)(b) of the Council Regulation, control of the mobile device business of Siemens AG (“Siemens device business”, Germany) by way of purchase of assets, and in respect of Germany and the UK, also by purchase of shares. I. THE PARTIES 2. BenQ is active in the communication and multimedia device business. Within this business it is active in the areas of digital displays, scanners and keyboards, mobile telephones (including communication devices like GSM mobile phones), digital projectors, storage devices, wireless technologies and electronic components. In the area of mobile telephones, BenQ sells its products mainly to other producers of telephones but also to a small extend under its own brand label to retailers and network operators. -

The Taiwan Fund, Inc ®

THE TAIWAN FUND,INC ® THE TAIWAN FUND, INC. Annual Report WHAT’S INSIDE August 31, 2009 Page Chairman’s Statement 2 Report of the Investment Manager 4 Portfolio Snapshot 7 Sector Allocation 8 Investments 9 Financial Statements 11 Notes to Financial Statements 14 Report of Independent Registered Public Accounting Firm 19 Other Information 20 Summary of Dividend Reinvestment and Cash Purchase Plan 22 Directors and Officers 25 CHAIRMAN’S STATEMENT Dear Shareholders, I am pleased to present the Annual Report of The Taiwan Fund, Inc. (the “Fund”) for the fiscal year ended August 31, 2009. The Fund’s net asset value (“NAV”) per share decreased by 10.29%* in U.S. dollar terms for the fiscal year. During the same period, the Taiwan Stock Exchange Index (the “TAIEX”) decreased by 7.13%* in U.S. dollar terms. The U.S. dollar depreciated by 4.14% against the NT dollar during this period. On August 31, 2009, the Fund’s shares were trading at a price equal to US$12.14 per share, reflecting a discount of 12.28% to the Fund’s NAV of $US13.84. The Fund’s shares were trading at a discount of 8.85% on August 31, 2008. During the year, we liquidated the Trust through which the Fund had invested in Taiwan securities since its inception. We believe that this will provide the Fund with greater investment flexibility, as it will no longer be subject to certain Taiwan regulations that restricted the investments made through the Trust. In connection with the liquida- tion of the Trust, we also restructured the investment management agreement the Fund has with HSBC Global Asset Management (Taiwan) Ltd.