Transcript of “In Quest of the Jewish Mary”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rosh Hashanah Ubhct Ubfkn

vbav atrk vkp, Rosh HaShanah ubhct ubfkn /UbkIe g©n§J 'UbFk©n Ubhc¨t Avinu Malkeinu, hear our voice. /W¤Ng k¥t¨r§G°h i¤r¤eo¥r¨v 'UbFk©n Ubhc¨t Avinu Malkeinu, give strength to your people Israel. /ohcIy ohH° jr© px¥CUb c,§ F 'UbFknUbh© ct¨ Avinu Malkeinu, inscribe us for blessing in the Book of Life. /vcIy v²b¨J Ubhkg J¥S©j 'UbFk©n Ubhc¨t Avinu Malkeinu, let the new year be a good year for us. 1 In the seventh month, hghc§J©v J¤s«jC on the first day of the month, J¤s«jk s¨j¤tC there shall be a sacred assembly, iIº,C©J ofk v®h§v°h a cessation from work, vgUr§T iIrf°z a day of commemoration /J¤s«et¨r§e¦n proclaimed by the sound v¨s«cg ,ftk§nkF of the Shofar. /U·Gg©, tO Lev. 23:24-25 Ub¨J§S¦e r¤J£t 'ok«ug¨v Qk¤n Ubh¥vO¡t '²h±h v¨T©t QUrC /c«uy o«uh (lWez¨AW) k¤J r¯b ehk§s©vk Ub²um±uuh¨,«um¦nC Baruch Atah Adonai, Eloheinu melech ha-olam, asher kid’shanu b’mitzvotav v’tzivanu l’hadlik ner shel (Shabbat v’shel) Yom Tov. We praise You, Eternal God, Sovereign of the universe, who hallows us with mitzvot and commands us to kindle the lights of (Shabbat and) Yom Tov. 'ok«ug¨v Qk¤n Ubh¥vO¡t '²h±h v¨T©t QUrC /v®Z©v i©n±Zk Ubgh°D¦v±u Ub¨n±H¦e±u Ub²h¡j¤v¤J Baruch Atah Adonai, Eloheinu melech ha-olam, shehecheyanu v’kiy’manu v’higiyanu, lazman hazeh. -

“Cliff Notes” 2021-2022 5781-5782

Jewish Day School “Cliff Notes” 2021-2022 5781-5782 A quick run-down with need-to-know info on: • Jewish holidays • Jewish language • Jewish terms related to prayer service SOURCES WE ACKNOWLEDGE THAT THE INFORMATION FOR THIS BOOKLET WAS TAKEN FROM: • www.interfaithfamily.com • Living a Jewish Life by Anita Diamant with Howard Cooper FOR MORE LEARNING, YOU MAY BE INTERESTED IN THE FOLLOWING RESOURCES: • www.reformjudaism.org • www.myjewishlearning.com • Jewish Literacy by Rabbi Joseph Telushkin • The Jewish Book of Why by Alfred J. Kolatch • The Jewish Home by Daniel B. Syme • Judaism for Dummies by Rabbi Ted Falcon and David Blatner Table of Contents ABOUT THE CALENDAR 5 JEWISH HOLIDAYS Rosh haShanah 6 Yom Kippur 7 Sukkot 8 Simchat Torah 9 Chanukah 10 Tu B’Shevat 11 Purim 12 Pesach (Passover) 13 Yom haShoah 14 Yom haAtzmaut 15 Shavuot 16 Tisha B’Av 17 Shabbat 18 TERMS TO KNOW A TO Z 20 About the calendar... JEWISH TIME- For over 2,000 years, Jews have juggled two calendars. According to the secular calendar, the date changes at midnight, the week begins on Sunday, and the year starts in the winter. According to the Hebrew calendar, the day begins at sunset, the week begins on Saturday night, and the new year is celebrated in the fall. The secular, or Gregorian calendar is a solar calendar, based on the fact that it takes 365.25 days for the earth to circle the sun. With only 365 days in a year, after four years an extra day is added to February and there is a leap year. -

CCAR Journal the Reform Jewish Quarterly

CCAR Journal The Reform Jewish Quarterly Halachah and Reform Judaism Contents FROM THE EDITOR At the Gates — ohrgJc: The Redemption of Halachah . 1 A. Brian Stoller, Guest Editor ARTICLES HALACHIC THEORY What Do We Mean When We Say, “We Are Not Halachic”? . 9 Leon A. Morris Halachah in Reform Theology from Leo Baeck to Eugene B . Borowitz: Authority, Autonomy, and Covenantal Commandments . 17 Rachel Sabath Beit-Halachmi The CCAR Responsa Committee: A History . 40 Joan S. Friedman Reform Halachah and the Claim of Authority: From Theory to Practice and Back Again . 54 Mark Washofsky Is a Reform Shulchan Aruch Possible? . 74 Alona Lisitsa An Evolving Israeli Reform Judaism: The Roles of Halachah and Civil Religion as Seen in the Writings of the Israel Movement for Progressive Judaism . 92 David Ellenson and Michael Rosen Aggadic Judaism . 113 Edwin Goldberg Spring 2020 i CONTENTS Talmudic Aggadah: Illustrations, Warnings, and Counterarguments to Halachah . 120 Amy Scheinerman Halachah for Hedgehogs: Legal Interpretivism and Reform Philosophy of Halachah . 140 Benjamin C. M. Gurin The Halachic Canon as Literature: Reading for Jewish Ideas and Values . 155 Alyssa M. Gray APPLIED HALACHAH Communal Halachic Decision-Making . 174 Erica Asch Growing More Than Vegetables: A Case Study in the Use of CCAR Responsa in Planting the Tri-Faith Community Garden . 186 Deana Sussman Berezin Yoga as a Jewish Worship Practice: Chukat Hagoyim or Spiritual Innovation? . 200 Liz P. G. Hirsch and Yael Rapport Nursing in Shul: A Halachically Informed Perspective . 208 Michal Loving Can We Say Mourner’s Kaddish in Cases of Miscarriage, Stillbirth, and Nefel? . 215 Jeremy R. -

סלח לנו S’Lach Lanu Forgive Us a Short Service for Selichot

סלח לנו S’lach Lanu Forgive Us a short service for Selichot Rabbi Rachel Barenblat 2 Shehecheyanu ָברְּוך ַאָּתה יי ֱֹאלֵהינּו ֶמ ְֶלך ָהעוָֹלם, ׁ ,Baruch atah Adonai Eloheinu melech ha’olam ֶשֶהֱחָינּו ְִוְקּיָמנּו ְוִהִּגיָענּו shehecheyanu vekiyemanu vehigiyanu ַלְּזַמן ַהֶּזה. .lazeman hazeh Blessed are You, Source of all being, Who has given us life, established us and allowed us to reach this sacred moment. Lach Amar Libi (Psalm 27:8) You לָך Lach :Called to my heart ַָאמר ִלבִּי Amar libi ,Come seek My face ַבְּקשׁוּ ָפָני Bakshuּ fanai .Come seek My grace ַבְּקשׁוּ ָפָני Bakshu fanai ,For Your love ֶאת ָפָּנִיך Et panayich ,Source of all הוי''ה Havayah .I will seek ֲַקבאֵשׁ Avakeish (melody from Nava Tehila; singable English by Rabbi David Markus) 3 Havdalah: Sanctifying Transition ִהֵנּה ֵאל ְישׁוָּעִתי, ֶאְבַטח ְולֹא ֶאְפָחד, ,Hineh el yeshuati, evtach v'lo efchad Ki ozi v'zimrat Yah, v'y'hi li l'yeshua. ִכי ָעִזּי ְוִזְמָרת יָהּ יְיָ, ַוְיִהי ִלי ִלישׁוָּעה: Ushavtem mayyim b'sasson mimainei וְּשַׁאְבֶתּם ַמִים ְבָּשׂשׂוֹן ִמַמַּעְיֵני ַהְישָׁוּעה: .ha-yeshua ַלָיי ַהְישָׁוּעה ַעל ַעְמּך ִבְרָכֶתך ֶסָּלה: L'Adonai ha-yeshua el amcha birchatecha יְיָ ְצָבאוֹת ִעָמּנוּ ִמְשָׂגּב ָלנוּ ֱאלֵהי ַיֲעקֹב ֶסָלה: .selah יְיָ ְצָבאוֹת ַאְשֵרי ָאָדם בֵֹּטַח ָבּך: Adonai tz'vaot imanu misgav lanu Elohei Ya'akov selah. יְיָ הוִֹשׁיָעה ַהֶמֶּלך ַיֲעֵננוּ ְביוֹם ָקְרֵאנוּ: .Adonai tz'vaot ashrei adam bote'ach bach ַלְיּהוִּדים ָהְיָתה אוָֹרה ְוִשְׂמָחה ְוָשׂשׂוֹן ִוָיקר: Adonai hoshia hamelech ya'aneinu b'yom ֵכּן ִתְּהֶיה ָלּנוּ, כּוֹס יְשׁוּעוֹת ֶאָשּׂא. .koreinu וְּבֵשׁם יְיָ ֶאְקָרא: ,La-yehudim haita ora v'simcha v'sasson v'ikar Ken tihyeh lanu. -

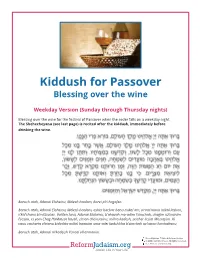

Kiddush for Passover Blessing Over the Wine

Kiddush for Passover Blessing over the wine Weekday Version (Sunday through Thursday nights) Blessing over the wine for the festival of Passover when the seder falls on a weekday night. The Shehecheyanu (see last page) is recited after the kiddush, immediately before drinking the wine. Baruch atah, Adonai Eloheinu, Melech haolam, borei p’ri hagafen. Baruch atah, Adonai Eloheinu, Melech haolam, asher bachar banu mikol am, v’rom’manu mikol lashon, v’kid’shanu b’mitzvotav. Vatiten lanu, Adonai Eloheinu, b’ahavah mo-adim l’simchah, chagim uz’manim l’sason, et yom Chag HaMatzot hazeh, z’man cheiruteinu, mikra kodesh, zeicher litziat Mitzrayim. Ki vanu vacharta v’otanu kidashta mikol haamim umo-adei kodsh’cha b’simchah uv’sason hinchaltanu. Baruch atah, Adonai m’kadeish Yisrael v’hazmanim. From Mishkan T’fi lah: A Reform Siddur. © 2007 by CCAR Press. All rights reserved. See more at ccarpress.org. Blessed are You, Adonai our God, Ruler of the world, Creator of the fruit of the vine. Blessed are You, Our God, Sovereign of the universe, who has chosen us from among the peoples, exalting us by hallowing us with mitzvot. In Your love, Adonai our God, You have given us feasts of gladness, and seasons of joy; this Festival of Pesach, season of our freedom, a sacred occasion, a remembrance of the Exodus from Egypt. For You have chosen us from all peoples and consecrated us to Your service, and given us the Festivals, a time of gladness and joy. Blessed are You, Adonai, who sanctifi es Israel and the Festivals. -

Shabirthday Guide

Happy S H A B B I R T H D A Y וַיְ ִהי בַּי ּוֹם ַה ׁ ְּשלִי ׁ ִשי יוֹם ֻהלֶּ ֶדת ֶאת־ ּפַ ְרע ֹה וַיַּעַשׂ ִמ ׁ ְש ֶּתה לְכָל־עֲבָ ָדיו. And on the third day, his birthday, Pharaoh made a banquet for all his officials. - Genesis 40:20 The very first recorded mention of a birthday celebration in Western literature is right here in the Torah, the Hebrew Bible. But birthdays have been celebrated for thousands of years in Eastern cultures, particularly evident in the Chinese tradition of “longevity noodles” — the longer the noodle you can slurp, the longer your life will be. Now that’s a ritual we can get behind. Whether you’re celebrating a birth date, birth month, star sign, or Chinese zodiac, we hope this guide helps elevate the centerpiece of your Shabbat — the once-in-a-lifetime miracle that is you. O N E T A B L E . O R G | @ O N E T A B L E S H A B B A T Light Shabbat candles! Birthday candles! More light means more joy. The light you create tonight will welcome your weekend, and sparkle long into your new year. בָּרוּךְ ַא ָּתה יְיָ ֱאל ֵֹהינוּ ֶמלֶךְ ָהעוֹלָם ֲא ׁ ֶשר ִק ְדּ ׁ ָשנוּ בְּ ִמצְוֹ ָתיו וְצִוָּנוּ לְ ַה ְדלִיק נֵר ׁ ֶשל ׁ ַשבָּת. Baruch Atah Adonai Eloheinu Melech ha’olam asher kidshanu b’mitzvotav vitzivanu l’hadlik ner shel Shabbat. Blessed is the Oneness that makes us holy through commandments and commands us to kindle the light of Shabbat. -

Selichot to Havdallah – Self-Reflection to Separation NFTY

Selichot to Havdallah – Self-Reflection to Separation NFTY-Missouri Valley LTI | September 3-5, 2010 | Kansas City, MO Melissa Frey – Kutz Camp Director/NFTY Associate Director Touchstone Text: "If one says: I shall sin and repent, sin and repent, no opportunity will be given to him to repent. If one says: I shall sin and the Day of Atonement will bring him forgiveness, the Day of Atonement will not bring him atonement. For transgressions between man and God the Day of Atonement brings atonement." - Talmud in Tractate Yoma 8, p. 2 Goals: This program is an opportunity to introduce teens to the period of repentance and reflection during the weeks before the High Holidays. The program gives them an opportunity to reflect on the past year and consider opportunities for change in the coming year. Objectives: Learn about the concept of forgiveness. Discuss the effect of their actions on others. Identify goals and opportunities for change in the coming year. Materials: Elul Self-Evaluation Worksheets Pens Space Needed: Any space where participants can spread out and have space to write. Detailed Procedure: 00:00-00:05 Introduction and framing with text from Appednix A 00:05-00:15 Readings of texts and stories about Selichot, repentance, forgiveness, Appendix B (multiple readers strategically placed around the room) 00:15-00:20 Introduction to Elul Self-Evaluation Worksheet, Appendix C Teens break into chevruta study groups to discuss texts on the sheet 00:20-00:35 Teens work independently to complete the Elul self-evaluation worksheet 00:35-00:40 -

Chevra Kadisha

CHEVRA KADISHA “I am with you in times of distress.” --Psalms 91:15 Introduction Kehillat Shaarei Torah’s vision includes being a dynamic, inclusive, welcoming modern orthodox community that celebrates Jewish life. We also want to provide inspirational learning opportunities and meaningful participation in religious life. As part of that vision, we are forming a Chevra Kadisha, a Holy Society that cares for the dying, the dead, and the bereaved in our community. This booklet is part of that effort. In these pages, we hope to provide basic information about our community’s practices surrounding end-of-life, and how those reflect traditional Jewish values and practices. Our hope in these pages is to de-mystify the mysterious and often-unspoken-about experience of dying and mourning. We hope that doing so opens us all up to more questioning, more learning, and more support of each other in difficult times, just as we celebrate joyous times together. Note: this version is a draft, prepared as a team effort by the KST Chevra Kadisha working group. We welcome your input, questions, and suggestions. Please send them to [email protected] 1 Preplanning Preplanning funeral arrangements is a wise and economical endeavour. It will save family members anguishing over choices at the time of loss, and may in most instances result in savings over time. Meeting with a representative of the funeral home can be done at any time. The Rabbi can provide the current list of services offered and prices, and you can decide and make appropriate arrangements with the funeral directors. -

Complete Text of Benjamin's Speech with Notes and Comments

Appendix: Complete Text of Benjamin's Speech with Notes and Comments PROLOGUE (MOSIAH 1:1–2:8) Benjamin’s Instructions to His Sons (Mosiah 1:1–8) 1And now there was no more *contention in *all the land of Zarahemla, among all the people who *belonged to king Benjamin, so that king Benjamin had *continual peace all the remainder of his days. 2And it came to pass that he had three sons; and he called their names *Mosiah, and *Helorum, and Helaman. And he caused that they should be taught in *all the language of his fathers, that thereby they might become *men of understanding; and that they might know concerning the *prophecies which had been spoken by the mouths of their fathers, which were *delivered them by the hand of the Lord. 3*And he also taught them concerning the records which were engraven on the *plates of brass, saying: My sons, *I would that ye should remember that were it not for *these plates, which contain these records and these commandments, we must have *suffered in ignorance, even at this present time, not knowing the *mysteries of God. 4For it were not possible that our father, Lehi, could have remembered all these things, to have taught them to his children, except it were for the help of these plates; for *he having been taught in the language of the Egyptians therefore he could read these engravings, and teach them to his children, that thereby they could teach them to their children, and so fullling the *commandments of God, even down to this present time. -

The Perfect Jewish Prayer for Your Vaccination - Alma

6/23/2021 The Perfect Jewish Prayer for Your Vaccination - Alma The Perfect Jewish Prayer for Your Vaccination A way to mark just how important this occasion is. By Sarah Flores Shannon April 6, 2021 Calvin Chan Wai Meng/Getty Images https://www.heyalma.com/the-perfect-jewish-prayer-for-your-vaccination/?utm_medium=social&utm_source=Instagram&utm_campaign=linkinbio&utm_content=la… 1/7 6/23/2021 The Perfect Jewish Prayer for Your Vaccination - Alma I recited my first-ever Shehechiyanu blessing in March 2020 over a Zoom call. I began my conversion journey two months earlier at a local synagogue when I started attending a monthly meeting of people interested in exploring a path toward Judaism. Our conversations ranged in topic and I greatly appreciated the opportunity to have a space to share my questions and curiosity. As it became clear that all future in-person gatherings would be canceled, I found small ways to feel connected to the Jewish community despite the lockdown. Like many across the United States, I began working from home in mid-March and felt that baking bread was an important quarantine activity that I needed to pick up. I quickly decided that baking challah would be the perfect opportunity to try out a new recipe ahead of Shabbat. At the start of our first virtual meeting, I was beaming with pride as I shared that I had successfully baked my first challah. As the group eagerly discussed the best challah recipes, one woman suggested that I recite the Shehechiyanu prayer to celebrate this moment. I had no clue what the Shehechiyanu was and quickly Googled the words. -

TISHREI Rosh Hashanah Begins on Friday Night. When

9 TISHREI The Molad: Monday night, 11:27 and 11 portions.1 The moon may be sanctified until Tuesday, the 15th, 5:49 p.m.2 The fall equinox: Thursday, Cheshvan 1, 9:00 a.m. Rosh HaShanah begins on Monday night. When lighting candles, we recite two blessings: L’hadlik ner shel Yom HaZikaron (“...to kindle the light of the Day of Remembrance”) and Shehecheyanu (“...who has granted us life...”). (In the blessing should be vocalized לזמן Shehecheyanu, the word lizman, with a chirik.) Tzedakah should be given before lighting the candles. Girls should begin lighting candles from the age when they can be trained in the observance of the mitzvah.3 Until marriage, girls should light only one candle. The Rebbe urged that all Jewish girls should light candles before Shabbos and festivals. Through the campaign mounted at his urging, Mivtza Neshek, the light of the Shabbos and the festivals has been brought to tens of thousands of Jewish homes. A man who lights candles should do so with a blessing, but should not recite the blessing Shehecheyanu.4 The Afternoon Service before Rosh HaShanah. “Regarding the issue of kavanah (intent) in prayer, for those who do not have the ability to focus their kavanah because of a lack of knowledge or due to other factors... it is sufficient that they have in mind a general intent: that their prayers be accepted before Him as if they were recited with all the intents 1. One portion equals 1/18 of a minute. 2. The times for sanctifying the moon are based on Jerusalem Standard Time. -

Guide for Sephardim Prepared by Rabbi Yonatan Nacson1

Laws for Praying at Home During the High Holidays A Practical Halachic Guide for Sephardim Prepared by Rabbi Yonatan Nacson1 Laws regarding Selichot 1. The Sephardic custom is to recite Selichot the entire month of Elul, starting from the day after Rosh Chodesh Elul.2 The Ashkenazic custom is to recite Selichot starting from the week of or before Rosh HaShanah.3 2. One may even recite the entire Selichot through technological means (such as a live hookup, the radio, or telephone.) However, if one merely listens to a recording of the Selichot, he may not recite it.4 It is even better to recite Selichot along with a larger minyan through a live hookup than to recite it along with a smaller minyan. This is common in Eretz Yisrael, where there are large Selichot minyanim, and many people follow along with a screen projecting the Selichot live. In such a case, it is better to recite it along with the screen than to form a separate and smaller minyan.5 3. When reciting Selichot without a minyan, one may recite the Thirteen Middot, provided that he recites them with the tune from the Torah reading.6 4. When reciting Selichot alone, one is not required to complete the pasuk for the Thirteen Middot (venakeh lo yenakeh).7 5. One who cannot recite Selichot with a minyan should refrain from saying the Aramaic parts.8 They are as .מחי ומסי (4 .מרנא דבשמיא (3 .דעני לעניי (2 .רחמנא (follows: 1 1 Most of the material in this document was excerpted from the of the Torah reading.