Chevra Kadisha

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rosh Hashanah Ubhct Ubfkn

vbav atrk vkp, Rosh HaShanah ubhct ubfkn /UbkIe g©n§J 'UbFk©n Ubhc¨t Avinu Malkeinu, hear our voice. /W¤Ng k¥t¨r§G°h i¤r¤eo¥r¨v 'UbFk©n Ubhc¨t Avinu Malkeinu, give strength to your people Israel. /ohcIy ohH° jr© px¥CUb c,§ F 'UbFknUbh© ct¨ Avinu Malkeinu, inscribe us for blessing in the Book of Life. /vcIy v²b¨J Ubhkg J¥S©j 'UbFk©n Ubhc¨t Avinu Malkeinu, let the new year be a good year for us. 1 In the seventh month, hghc§J©v J¤s«jC on the first day of the month, J¤s«jk s¨j¤tC there shall be a sacred assembly, iIº,C©J ofk v®h§v°h a cessation from work, vgUr§T iIrf°z a day of commemoration /J¤s«et¨r§e¦n proclaimed by the sound v¨s«cg ,ftk§nkF of the Shofar. /U·Gg©, tO Lev. 23:24-25 Ub¨J§S¦e r¤J£t 'ok«ug¨v Qk¤n Ubh¥vO¡t '²h±h v¨T©t QUrC /c«uy o«uh (lWez¨AW) k¤J r¯b ehk§s©vk Ub²um±uuh¨,«um¦nC Baruch Atah Adonai, Eloheinu melech ha-olam, asher kid’shanu b’mitzvotav v’tzivanu l’hadlik ner shel (Shabbat v’shel) Yom Tov. We praise You, Eternal God, Sovereign of the universe, who hallows us with mitzvot and commands us to kindle the lights of (Shabbat and) Yom Tov. 'ok«ug¨v Qk¤n Ubh¥vO¡t '²h±h v¨T©t QUrC /v®Z©v i©n±Zk Ubgh°D¦v±u Ub¨n±H¦e±u Ub²h¡j¤v¤J Baruch Atah Adonai, Eloheinu melech ha-olam, shehecheyanu v’kiy’manu v’higiyanu, lazman hazeh. -

Download Scrolls SW Affidavit

Case 1:21-mj-00837-PK Document 1 Filed 07/20/21 Page 1 of 18 PageID #: 1 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT EASTERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – X IN RE THE SEIZURE OF: AFFIDAVIT IN SUPPORT OF SEIZURE WARRANT TWENTY-ONE JEWISH FUNERAL SCROLLS, AND WRIT OF ASSISTANCE PINKAS MANUSCRIPTS AND COMMUNITY RECORDS FROM COMMUNITIES IN 21-MJ-837 ROMANIA, HUNGARY, UKRAINE AND SLOVAKIA AS SET FORTH IN EXHIBIT A (Kuo, M.J.) HERETO – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – X EASTERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK, SS: MEGAN BUCKLEY, Special Agent with the Department of Homeland Security, being duly sworn, deposes and says: 1. I am a special agent with the Department of Homeland Security – Homeland Security Investigations (“HSI”) and have been so employed by HSI and its predecessor agencies for approximately 16 years. I am currently assigned to the Cultural Property, Art, and Antiquities Group at HSI. I have investigated, among other matters, criminal activity related to artwork and antiquities, including theft, fraud, and other crimes involving highly regarded works of art such as paintings, sculptures, and antiquities. I have personally participated in the instant investigation. 2. During the course of my employment with HSI, I have executed dozens of search warrants at personal residences, and I have employed various investigative techniques, including physical and electronic surveillance, consensual recording, seizure and review of digital and physical evidence, utilization of confidential human sources and cooperating witnesses, Case 1:21-mj-00837-PK Document 1 Filed 07/20/21 Page 2 of 18 PageID #: 2 undercover operations, and financial analysis. I have been trained on the laws relating to searches and seizures at the Federal Law Enforcement Training Facility in Glynco, Georgia. -

“Cliff Notes” 2021-2022 5781-5782

Jewish Day School “Cliff Notes” 2021-2022 5781-5782 A quick run-down with need-to-know info on: • Jewish holidays • Jewish language • Jewish terms related to prayer service SOURCES WE ACKNOWLEDGE THAT THE INFORMATION FOR THIS BOOKLET WAS TAKEN FROM: • www.interfaithfamily.com • Living a Jewish Life by Anita Diamant with Howard Cooper FOR MORE LEARNING, YOU MAY BE INTERESTED IN THE FOLLOWING RESOURCES: • www.reformjudaism.org • www.myjewishlearning.com • Jewish Literacy by Rabbi Joseph Telushkin • The Jewish Book of Why by Alfred J. Kolatch • The Jewish Home by Daniel B. Syme • Judaism for Dummies by Rabbi Ted Falcon and David Blatner Table of Contents ABOUT THE CALENDAR 5 JEWISH HOLIDAYS Rosh haShanah 6 Yom Kippur 7 Sukkot 8 Simchat Torah 9 Chanukah 10 Tu B’Shevat 11 Purim 12 Pesach (Passover) 13 Yom haShoah 14 Yom haAtzmaut 15 Shavuot 16 Tisha B’Av 17 Shabbat 18 TERMS TO KNOW A TO Z 20 About the calendar... JEWISH TIME- For over 2,000 years, Jews have juggled two calendars. According to the secular calendar, the date changes at midnight, the week begins on Sunday, and the year starts in the winter. According to the Hebrew calendar, the day begins at sunset, the week begins on Saturday night, and the new year is celebrated in the fall. The secular, or Gregorian calendar is a solar calendar, based on the fact that it takes 365.25 days for the earth to circle the sun. With only 365 days in a year, after four years an extra day is added to February and there is a leap year. -

Chevra Kadisha Version2

Congregation Ahavath Sholom Guide for Jewish Burial and Mourning Edited by Rabbi Andrew Bloom The first steps to take when a loved one dies are to call your Rabbi and to call a funeral home. Contacting your family Rabbi before finalizing any burial plans is very important. Aside from aiding you with adhering to Conservative Jewish law, your Rabbi has experience with bereaved families and can discuss with you final wishes of the departed, and other special situations that you may have to consider in planning a funeral, burial, and mourning observance. Your Rabbi’s input will make the decisions you need to face easier and the entire process far less daunting. The passing of a loved one can be a very stressful and traumatic time. You should not try to go through this alone. It is our responsibility as part of the Jewish community to help you through this time in your life. So, contact Congregation Ahavath Sholom as soon as you can. We consider this to be a Rabbinic Emergency. Do not hesitate to call, be it late at night, on the Sabbath, or during a Jewish holiday. There will always be someone for you to contact in case of death. During hours when the synagogue office is open, call Congregation Ahavath Sholom main number, 817- 731-4721 and you will be put through to Rabbi Andrew Bloom. When the office is closed call Congregation Ahavath Sholom main number, listen to the voice prompts, and dial the extension 105 for Rabbi Bloom There will be a message on how to contact the Rabbi, or whomever is covering for the Rabbi in his absence. -

CCAR Journal the Reform Jewish Quarterly

CCAR Journal The Reform Jewish Quarterly Halachah and Reform Judaism Contents FROM THE EDITOR At the Gates — ohrgJc: The Redemption of Halachah . 1 A. Brian Stoller, Guest Editor ARTICLES HALACHIC THEORY What Do We Mean When We Say, “We Are Not Halachic”? . 9 Leon A. Morris Halachah in Reform Theology from Leo Baeck to Eugene B . Borowitz: Authority, Autonomy, and Covenantal Commandments . 17 Rachel Sabath Beit-Halachmi The CCAR Responsa Committee: A History . 40 Joan S. Friedman Reform Halachah and the Claim of Authority: From Theory to Practice and Back Again . 54 Mark Washofsky Is a Reform Shulchan Aruch Possible? . 74 Alona Lisitsa An Evolving Israeli Reform Judaism: The Roles of Halachah and Civil Religion as Seen in the Writings of the Israel Movement for Progressive Judaism . 92 David Ellenson and Michael Rosen Aggadic Judaism . 113 Edwin Goldberg Spring 2020 i CONTENTS Talmudic Aggadah: Illustrations, Warnings, and Counterarguments to Halachah . 120 Amy Scheinerman Halachah for Hedgehogs: Legal Interpretivism and Reform Philosophy of Halachah . 140 Benjamin C. M. Gurin The Halachic Canon as Literature: Reading for Jewish Ideas and Values . 155 Alyssa M. Gray APPLIED HALACHAH Communal Halachic Decision-Making . 174 Erica Asch Growing More Than Vegetables: A Case Study in the Use of CCAR Responsa in Planting the Tri-Faith Community Garden . 186 Deana Sussman Berezin Yoga as a Jewish Worship Practice: Chukat Hagoyim or Spiritual Innovation? . 200 Liz P. G. Hirsch and Yael Rapport Nursing in Shul: A Halachically Informed Perspective . 208 Michal Loving Can We Say Mourner’s Kaddish in Cases of Miscarriage, Stillbirth, and Nefel? . 215 Jeremy R. -

A Guide to Burial in Israel for US Members

A Guide to Burial in Israel for US Members 1 Contents • Introduction 4 • Why Israel? 5 • Eretz Hachaim Cemetery 6 • Costs for a Funeral in the US Section at Eretz Hachaim Cemetery 7 • Purchasing a Plot at Eretz Hachaim Cemetery 7 • Transporting the Deceased to Israel 9 • Funeral & Burial Services 9 • Cemetery Maintenance Fee 9 • United Synagogue Members who have made Aliyah 10 • Israeli Funerals 10 • Sitting Shiva in Israel 11 • Choosing a Stone 12 • Stone Settings 14 • Halacha - While the Deceased is in Transit 14 • Useful Contact Details 15 • Glossary of Hebrew Terms 18 • Further Reading 19 2 3 Introduction Why Israel? Buying a burial plot can be an emotional act. Whether you are The place where we choose to be buried says much about the meaning purchasing one for yourself or for the burial of a loved one, we at the of our lives. Choosing to be buried as a Jew in any country is a United Synagogue wish you and your family strength, and Arichut declaration of our faith and loyalties. Purchasing a plot in Israel further Yamim as you embark on this process. links our destiny to the Jewish people, its land and its faith. At the outset of our nation, Abraham purchases a burial place for his wife Sarah at This booklet is a practical and halachic guide to the process of buying the Cave of Machpela in Hebron marking the start of a distinctive family a burial plot in Israel with the US and for arranging a funeral and stone tradition which would emerge into a nation with a profound connection setting there. -

סלח לנו S’Lach Lanu Forgive Us a Short Service for Selichot

סלח לנו S’lach Lanu Forgive Us a short service for Selichot Rabbi Rachel Barenblat 2 Shehecheyanu ָברְּוך ַאָּתה יי ֱֹאלֵהינּו ֶמ ְֶלך ָהעוָֹלם, ׁ ,Baruch atah Adonai Eloheinu melech ha’olam ֶשֶהֱחָינּו ְִוְקּיָמנּו ְוִהִּגיָענּו shehecheyanu vekiyemanu vehigiyanu ַלְּזַמן ַהֶּזה. .lazeman hazeh Blessed are You, Source of all being, Who has given us life, established us and allowed us to reach this sacred moment. Lach Amar Libi (Psalm 27:8) You לָך Lach :Called to my heart ַָאמר ִלבִּי Amar libi ,Come seek My face ַבְּקשׁוּ ָפָני Bakshuּ fanai .Come seek My grace ַבְּקשׁוּ ָפָני Bakshu fanai ,For Your love ֶאת ָפָּנִיך Et panayich ,Source of all הוי''ה Havayah .I will seek ֲַקבאֵשׁ Avakeish (melody from Nava Tehila; singable English by Rabbi David Markus) 3 Havdalah: Sanctifying Transition ִהֵנּה ֵאל ְישׁוָּעִתי, ֶאְבַטח ְולֹא ֶאְפָחד, ,Hineh el yeshuati, evtach v'lo efchad Ki ozi v'zimrat Yah, v'y'hi li l'yeshua. ִכי ָעִזּי ְוִזְמָרת יָהּ יְיָ, ַוְיִהי ִלי ִלישׁוָּעה: Ushavtem mayyim b'sasson mimainei וְּשַׁאְבֶתּם ַמִים ְבָּשׂשׂוֹן ִמַמַּעְיֵני ַהְישָׁוּעה: .ha-yeshua ַלָיי ַהְישָׁוּעה ַעל ַעְמּך ִבְרָכֶתך ֶסָּלה: L'Adonai ha-yeshua el amcha birchatecha יְיָ ְצָבאוֹת ִעָמּנוּ ִמְשָׂגּב ָלנוּ ֱאלֵהי ַיֲעקֹב ֶסָלה: .selah יְיָ ְצָבאוֹת ַאְשֵרי ָאָדם בֵֹּטַח ָבּך: Adonai tz'vaot imanu misgav lanu Elohei Ya'akov selah. יְיָ הוִֹשׁיָעה ַהֶמֶּלך ַיֲעֵננוּ ְביוֹם ָקְרֵאנוּ: .Adonai tz'vaot ashrei adam bote'ach bach ַלְיּהוִּדים ָהְיָתה אוָֹרה ְוִשְׂמָחה ְוָשׂשׂוֹן ִוָיקר: Adonai hoshia hamelech ya'aneinu b'yom ֵכּן ִתְּהֶיה ָלּנוּ, כּוֹס יְשׁוּעוֹת ֶאָשּׂא. .koreinu וְּבֵשׁם יְיָ ֶאְקָרא: ,La-yehudim haita ora v'simcha v'sasson v'ikar Ken tihyeh lanu. -

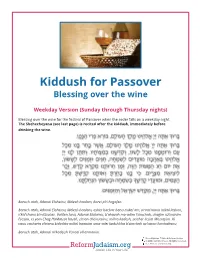

Kiddush for Passover Blessing Over the Wine

Kiddush for Passover Blessing over the wine Weekday Version (Sunday through Thursday nights) Blessing over the wine for the festival of Passover when the seder falls on a weekday night. The Shehecheyanu (see last page) is recited after the kiddush, immediately before drinking the wine. Baruch atah, Adonai Eloheinu, Melech haolam, borei p’ri hagafen. Baruch atah, Adonai Eloheinu, Melech haolam, asher bachar banu mikol am, v’rom’manu mikol lashon, v’kid’shanu b’mitzvotav. Vatiten lanu, Adonai Eloheinu, b’ahavah mo-adim l’simchah, chagim uz’manim l’sason, et yom Chag HaMatzot hazeh, z’man cheiruteinu, mikra kodesh, zeicher litziat Mitzrayim. Ki vanu vacharta v’otanu kidashta mikol haamim umo-adei kodsh’cha b’simchah uv’sason hinchaltanu. Baruch atah, Adonai m’kadeish Yisrael v’hazmanim. From Mishkan T’fi lah: A Reform Siddur. © 2007 by CCAR Press. All rights reserved. See more at ccarpress.org. Blessed are You, Adonai our God, Ruler of the world, Creator of the fruit of the vine. Blessed are You, Our God, Sovereign of the universe, who has chosen us from among the peoples, exalting us by hallowing us with mitzvot. In Your love, Adonai our God, You have given us feasts of gladness, and seasons of joy; this Festival of Pesach, season of our freedom, a sacred occasion, a remembrance of the Exodus from Egypt. For You have chosen us from all peoples and consecrated us to Your service, and given us the Festivals, a time of gladness and joy. Blessed are You, Adonai, who sanctifi es Israel and the Festivals. -

The Laws and Customs of Mourning

COMFORTING THE MOURNERS The Laws and Customs of Mourning Compiled by Rabbi Zalman Manela Table Of Contents A Letter of Consolation ................................................................................................................................. 2 Before the Burial ........................................................................................................................................... 4 Burial Preparations ....................................................................................................................................... 5 The Funeral ................................................................................................................................................... 5 Honoring the Deceased................................................................................................................................. 6 Burial ............................................................................................................................................................. 6 After the Burial .............................................................................................................................................. 7 Tearing the Garments ................................................................................................................................... 7 The First Meal ............................................................................................................................................... 8 Praying and Saying Kaddish -

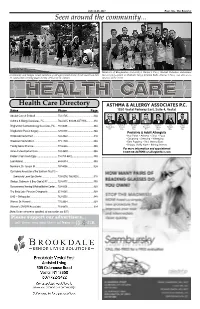

Seen Around the Community

July 14-20, 2017 Page 31A - The Reporter Seen around the community... Members of Binghamton University’s Harpur’s Ferry Student Volunteer Ambulance Community and Temple Israel members of all ages joined in the Torah march on July Service participated in Chabad’s Mega Challah Bake. Harpur’s Ferry was also a co- 22, with some carrying plush Torahs. (Photo by G. Heller) sponsor of the event. Health Care Directory ASTHMA & ALLERGY ASSOCIATES P.C. 1550 Vestal Parkway East, Suite 4, Vestal Name Phone Page Absolut Care at Endicott ...................................754-2705 ........................................32A Asthma & Allergy Associates, PC .....................766-0235, 800-88-ASTHMA ...........31A Elliot Mariah M. Rizwan Joseph Stella M. Julie Shaan Binghamton Gastroenterology Associates, PC ..... 772-0639 .............................................33A Rubinstein, Pieretti, Khan, Flanagan, Castro, McNairn, Waqar, M.D M.D. M.D. M.D. M.D. M.D. M.D. Binghamton Plastic Surgery .............................729-0101 ........................................34A Pediatric & Adult Allergists Brookdale Vestal East ......................................722-3422 ........................................31A • Hay Fever • Asthma • Sinus • Food • Coughing • Sneezing • Wheezing Brookdale Vestal West .....................................771-1700 ........................................33A • Ears Popping • Red, Watery Eyes Family Dental Practice ......................................772-6636 ........................................35A • Drippy, Stuy -

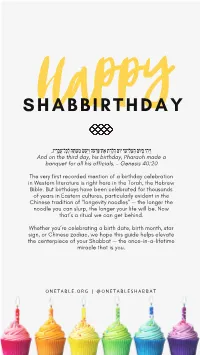

Shabirthday Guide

Happy S H A B B I R T H D A Y וַיְ ִהי בַּי ּוֹם ַה ׁ ְּשלִי ׁ ִשי יוֹם ֻהלֶּ ֶדת ֶאת־ ּפַ ְרע ֹה וַיַּעַשׂ ִמ ׁ ְש ֶּתה לְכָל־עֲבָ ָדיו. And on the third day, his birthday, Pharaoh made a banquet for all his officials. - Genesis 40:20 The very first recorded mention of a birthday celebration in Western literature is right here in the Torah, the Hebrew Bible. But birthdays have been celebrated for thousands of years in Eastern cultures, particularly evident in the Chinese tradition of “longevity noodles” — the longer the noodle you can slurp, the longer your life will be. Now that’s a ritual we can get behind. Whether you’re celebrating a birth date, birth month, star sign, or Chinese zodiac, we hope this guide helps elevate the centerpiece of your Shabbat — the once-in-a-lifetime miracle that is you. O N E T A B L E . O R G | @ O N E T A B L E S H A B B A T Light Shabbat candles! Birthday candles! More light means more joy. The light you create tonight will welcome your weekend, and sparkle long into your new year. בָּרוּךְ ַא ָּתה יְיָ ֱאל ֵֹהינוּ ֶמלֶךְ ָהעוֹלָם ֲא ׁ ֶשר ִק ְדּ ׁ ָשנוּ בְּ ִמצְוֹ ָתיו וְצִוָּנוּ לְ ַה ְדלִיק נֵר ׁ ֶשל ׁ ַשבָּת. Baruch Atah Adonai Eloheinu Melech ha’olam asher kidshanu b’mitzvotav vitzivanu l’hadlik ner shel Shabbat. Blessed is the Oneness that makes us holy through commandments and commands us to kindle the light of Shabbat. -

Selichot to Havdallah – Self-Reflection to Separation NFTY

Selichot to Havdallah – Self-Reflection to Separation NFTY-Missouri Valley LTI | September 3-5, 2010 | Kansas City, MO Melissa Frey – Kutz Camp Director/NFTY Associate Director Touchstone Text: "If one says: I shall sin and repent, sin and repent, no opportunity will be given to him to repent. If one says: I shall sin and the Day of Atonement will bring him forgiveness, the Day of Atonement will not bring him atonement. For transgressions between man and God the Day of Atonement brings atonement." - Talmud in Tractate Yoma 8, p. 2 Goals: This program is an opportunity to introduce teens to the period of repentance and reflection during the weeks before the High Holidays. The program gives them an opportunity to reflect on the past year and consider opportunities for change in the coming year. Objectives: Learn about the concept of forgiveness. Discuss the effect of their actions on others. Identify goals and opportunities for change in the coming year. Materials: Elul Self-Evaluation Worksheets Pens Space Needed: Any space where participants can spread out and have space to write. Detailed Procedure: 00:00-00:05 Introduction and framing with text from Appednix A 00:05-00:15 Readings of texts and stories about Selichot, repentance, forgiveness, Appendix B (multiple readers strategically placed around the room) 00:15-00:20 Introduction to Elul Self-Evaluation Worksheet, Appendix C Teens break into chevruta study groups to discuss texts on the sheet 00:20-00:35 Teens work independently to complete the Elul self-evaluation worksheet 00:35-00:40