Biography and Homoeopathy in Bengal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Postcoloniality, Science Fiction and India Suparno Banerjee Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, Banerjee [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2010 Other tomorrows: postcoloniality, science fiction and India Suparno Banerjee Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Banerjee, Suparno, "Other tomorrows: postcoloniality, science fiction and India" (2010). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3181. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3181 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. OTHER TOMORROWS: POSTCOLONIALITY, SCIENCE FICTION AND INDIA A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In The Department of English By Suparno Banerjee B. A., Visva-Bharati University, Santiniketan, West Bengal, India, 2000 M. A., Visva-Bharati University, Santiniketan, West Bengal, India, 2002 August 2010 ©Copyright 2010 Suparno Banerjee All Rights Reserved ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My dissertation would not have been possible without the constant support of my professors, peers, friends and family. Both my supervisors, Dr. Pallavi Rastogi and Dr. Carl Freedman, guided the committee proficiently and helped me maintain a steady progress towards completion. Dr. Rastogi provided useful insights into the field of postcolonial studies, while Dr. Freedman shared his invaluable knowledge of science fiction. Without Dr. Robin Roberts I would not have become aware of the immensely powerful tradition of feminist science fiction. -

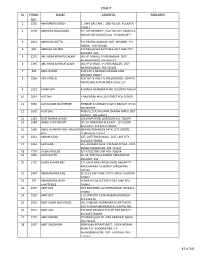

Sl Form No. Name Address Remarks

STARLIT SL FORM NAME ADDRESS REMARKS NO. 1 2235 ABHIMANYU SINGH 2, UMA DAS LANE , 2ND FLOOR , KOLKATA- 700013 2 1998 ABHISHEK MAJUMDER R.P. APPARTMENT , FLAT NO-303 PRAFULLA KANAN (W) KOLKATA-101 P.S-BAGUIATI 3 1922 ABHRANIL DUTTA P.O-PRAFULLANAGAR DIST-24PGS(N) , P.S- HABRA , PIN-743268 4 860 ABINASH HALDER 139 BELGACHIA EAST HB-6 SALT LAKE CITY KOLKATA -106 5 2271 ABU HENA MONIRUL ALAM VILL+P.O-MILKI, P.S-REJINAGAR DIST- MURSHIDABAD, PIN-742163 6 1395 ABU HENA SAHINUR ALAM VILL+P.O-MILKI , P.S-REGINAGAR , DIST- MURSHIDABAD, PIN-742163 7 446 ABUL HASAN B 32 1AH 3 MIAJAN OSTAGAR LANE KOLKATA 700017 8 3286 ADA AFREEN FLAT NO 9I PINES IV GREENWOOD SONATA NEWTOWN ACTION AREA II KOL 157 9 1623 ADHIR GIRI 8 DURGA CHANDRA ROAD KOLKATA 700014 10 2807 AJIT DAS 6 RAJENDRA MULLICK STREET KOL-700007 11 3650 AJIT KUMAR MUKHERJEE SHIBBARI K,S ROAD P.O &P.S NAIHATI DT 24 PGS NORTH 12 1602 AJOY DAS PO&VILL SOUTH GARIA CHARAK MATH DIST 24 PGS S PIN 743613 13 1261 AJOY KUMAR GHOSH 326 JAWPUR RD. DUMDUM KOL-700074 14 1584 AKASH CHOUDHURY DD-19, NARAYANTALA EAST , 1ST FLOOR BAGUIATI , KOLKATA-700059 15 2460 AKHIL CHANDRA ROY MNJUSRI 68 RANI RASHMONI PATH CITY CENTRE ROY DURGAPUR 713216 16 2311 AKRAM AZAD 227, DUTTABAD ROAD, SALT LAKE CITY , KOLKATA-700064 17 1441 ALIP JANA VILL-KHAMAR CHAK P.O-NILKUNTHIA , DIST- PURBA MIDNAPORE PIN-721627 18 2797 ALISHA BEGUM 5/2 B DOCTOR LANE KOL-700014 19 1956 ALOK DUTTA AC-64, PRAFULLA KANAN KRISHNAPUR KOLKATA -101 20 1719 ALOKE KUMAR DEY 271 SASHI BABU ROAD SAHID NAGAR PO KANCHAPARA PS BIZPUR 24PGSN PIN 743145 21 3447 -

DOCUMENTO De TRABAJO DOCUMENTO DE TRABAJO

InstitutoINSTITUTO de Economía DE ECONOMÍA TRABAJO de DOCUMENTO DOCUMENTO DE TRABAJO 423 2012 Marry for What? Caste and Mate Selection in Modern India Abhijit Banerjee, Esther Duflo, Maitreesh Ghatak, Jeanne Lafortune. www.economia.puc.cl • ISSN (edición impresa) 0716-7334 • ISSN (edición electrónica) 0717-7593 Versión impresa ISSN: 0716-7334 Versión electrónica ISSN: 0717-7593 PONTIFICIA UNIVERSIDAD CATOLICA DE CHILE INSTITUTO DE ECONOMIA Oficina de Publicaciones Casilla 76, Correo 17, Santiago www.economia.puc.cl MARRY FOR WHAT? CASTE AND MATE SELECTION IN MODERN INDIA Abhijit Banerjee Esther Duflo Maitreesh Ghatak Jeanne Lafortune* Documento de Trabajo Nº 423 Santiago, Marzo 2012 * [email protected] INDEX ABSTRACT INTRODUCTION 1 2. MODEL 5 2.1 Set-up 5 2.2 An important caveat: preferences estimation with unobserved attributes 8 2.3 Stable matching patterns 8 3. SETTING AND DATA 13 3.1 Setting: the search process 13 3.2 Sample and data collection 13 3.3 Variable construction 14 3.4 Summary statistics 15 4. ESTIMATING PREFERENCES 17 4.1 Basic empirical strategy 17 4.2 Results 18 4.3 Heterogeneity in preferences 20 4.4 Do these coefficients really reflect preferences? 21 4.4.1 Strategic behavior 21 4.4.2 What does caste signal? 22 4.5 Do these preferences reflect dowry? 24 5. PREDICTING OBSERVED MATCHING PATTERNS 24 5.1 Empirical strategy 25 5.2 Results 27 5.2.1 Who stays single? 27 5.2.2 Who marries whom? 28 6. THE ROLE OF CASTE PREFERENCES IN EQUILIBRIUM 30 6.1 Model Predictions 30 6.2 Simulations 30 7. -

Biography and Homoeopathy in Bengal

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Apollo Biography and Homoeopathy in Bengal: Colonial Lives of a European Heterodoxy1 Short Title: Biography and Homoeopathy in Bengal Centre for Research in Arts Social Science and Humanities, University of Cambridge, UK Email: [email protected] Despite being recognised as a significant literary mode in understanding the advent of modern self, biographies as a genre have received relatively less attention from South Asian historians. Likewise, histories of science and healing in British India have largely ignored the colonial trajectories of those sectarian, dissenting, supposedly pseudo-sciences and medical heterodoxies that flourished in Europe since the late eighteenth century. This article addresses these gaps in the historiography to identify biographies as a principal mode through which an incipient, ‘heterodox’ western science like homoeopathy could consolidate and sustain itself in Bengal. In recovering the cultural history of a category that the state archives render largely invisible, this article contends biographies as more than a mere repository of individual lives, and to be a veritable site of power. In bringing histories of print and publishing, histories of medicine and histories of life writing practices together, it pursues two broad themes: First, it analyses the sociocultural strategies and networks by which scientific doctrines and concepts are translated across cultural borders. It explores the relation between medical commerce, print capital and therapeutic knowledge, to illustrate that acculturation of medical science necessarily drew upon and reinforced local constellations of class, kinship and religion. Second, it simultaneously reflects upon the expanding genre of homoeopathic biographies published since the mid nineteenth century: on their features, relevance and functions, examining in particular, the contemporary status of biography vis-à-vis ‘history’ in writing objective pasts. -

Oswaal ISC 11Th History Self Assessment Paper

Time : 3 Hours Maximum Marks : 80 HISTORY ISC Solutions Self Assessment Paper 1 PART I 1. (i) Lord Curzon toured East Bengal to mobilise support of the Muslims of these areas for implementing the Partition plan. (ii) The main purpose of Swadeshi Movement was to organise constructive activities instead of appealing to the British authority. (iii) Phillip Francis, the Councilor of Lord Warren Hastings. (iv) Raja Ram Mohan Roy. (v) Swami Dayanand Saraswati, Lala Hans Raj, Pandit Guru Dutt and Lala Lajpat Rai are some of the reformers of the Arya Samaj. (vi) Dinabandhu Mitra. (vii) Mahatma Gandhi founded the Satyagraha Ashram to teach the Indians about the idea of Satyagraha. (viii) Nehru report was drafted by a committee headed by Motilal Nehru in August 1928. (ix) The seven states were Britain, Belgium, France, Portugal, Spain, Germany and Holland. (x) England. (xi) Nicolas II was the last Czar of Russia. (xii) Treaty of St. Germain. (xiii) Germany and Soviet Union. (xiv) 9 – 1 Chief Judge and 8 Associate Judges. (xv) Some of the ways are: (a) Subsidies were given to agriculture. (b) Guarantee of price was given. (c) Marketing Boards were established which regulated price by restricting output. (d) In ship building, cotton industry attempts were made to boost up production. (xvi) Czarina or wife of Czar Nicholas II. (xvii) The outstanding achievement of Mussolini was the settlement of dispute with the Papacy. By the Lateran Treaty of 1929, the Pope recognised Kingdom of Italy with Rome as capital. The Fascist government recognised Vatican City as a sovereign state. (xviii) On June 30, 1934, a number of enemies and critics of Hitler were executed. -

The Bengal Renaissance : a Critique

20th European Conference of Modern South Asian Studies Manchester (UK), 8th – 11th July 2008 Panel 9: Bengal Studies The Bengal Renaissance : a critique by Prof. Soumyajit Samanta Dept. of English, University of North Bengal, Darjeeling West Bengal, India, 734013 Preamble This paper welcomes listeners to a fresh review of the phenomenon known as The Bengal Renaissance. It is a fact that during the early 19th century the Bengali intellect learned to raise questions about issues & beliefs under the impact of British rule in the Indian subcontinent. In a unique manner, Bengal had witnessed an intellectual awakening that deserves to be called a Renaissance in European style. The new intellectual avalanche of European knowledge, especially philosophy, history, science & literature through the medium of education in English may be said to have affected contemporary mind & life very radically. Renaissance minds included Raja Rammohan Roy (1774-1833), Henry Louis Vivian Derozio (1809-1831) & his radical disciples Debendranath Tagore (1817-1905) & his followers, Akshay Kumar Datta (1820-1826), Iswar Chandra Vidyasagar (1820-91), Michael Madhusudan Dutt (1824-73), Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay (1838-94), & Swami Vivekananda (1863-1902). 1 The major vehicle & expressions of the Bengal Renaissance were: • the appearance of a large number of newspapers & periodicals • the growth of numerous societies & associations • a number of reform movements, both religious & social These served as so many forums for different dialogues & exchanges that the Renaissance produced. The major achievements of the Renaissance were: • a secular struggle for rational freethinking • growth of modern Bengali literature • spread of Western education & ideas • fervent & diverse intellectual inquiry • rise of nationalistic ideas • rise of nationalism challenged the foreign subjugation of country In British Orientalism & the Bengal Renaissance (1969), David Kopf considers the idea of R(r)enaissance (with a lower case r) as synonymous with modernization or revitalization. -

The High Court at Calcutta 150 Years : an Overview

1 2 The High Court at Calcutta 150 Years : An Overview 3 Published by : The Indian Law Institute (West Bengal State Unit) iliwbsu.in Printed by : Ashutosh Lithographic Co. 13, Chidam Mudi Lane Kolkata 700 006 ebook published by : Indic House Pvt. Ltd. 1B, Raja Kalikrishna Lane Kolkata 700 005 www.indichouse.com Special Thanks are due to the Hon'ble Justice Indira Banerjee, Treasurer, Indian Law Institute (WBSU); Mr. Dipak Deb, Barrister-at-Law & Sr. Advocate, Director, ILI (WBSU); Capt. Pallav Banerjee, Advocate, Secretary, ILI (WBSU); and Mr. Pradip Kumar Ghosh, Advocate, without whose supportive and stimulating guidance the ebook would not have been possible. Indira Banerjee J. Dipak Deb Pallav Banerjee Pradip Kumar Ghosh 4 The High Court at Calcutta 150 Years: An Overview तदॆततत- क्षत्रस्थ क्षत्रैयद क्षत्र यद्धर्म: ।`& 1B: । 1Bद्धर्म:1Bत्पटैनास्ति।`抜֘टै`抜֘$100 नास्ति ।`抜֘$100000000स्ति`抜֘$1000000000000स्थक्षत्रैयदत । तस्थ क्षत्रै यदर्म:।`& 1Bण । ᄡC:\Users\सत धर्म:" ।`&ﲧ1Bशैसतेधर्मेण।h अय अभलीयान् भलीयौसमाशयनास्ति।`抜֘$100000000 भलीयान् भलीयौसमाशयसर्म: ।`& य राज्ञाज्ञा एवम एवर्म: ।`& 1B ।। Law is the King of Kings, far more powerful and rigid than they; nothing can be mightier than Law, by whose aid, as by that of the highest monarch, even the weak may prevail over the strong. Brihadaranyakopanishad 1-4.14 5 Copyright © 2012 All rights reserved by the individual authors of the works. All rights in the compilation with the Members of the Editorial Board. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the copyright holders. -

Colonial India in Children's Literature

COLONIAL INDIA IN CHILDREN’S LITERATURE SUPRIYA GOSWAMI NEW YORK AND LONDON First published 2012 by Routledge 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017 Simultaneously published in the UK by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2012 Taylor & Francis The right of Supriya Goswami to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. Trademark Notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Goswami, Supriya. Colonial India in children’s literature / Supriya Goswami. p. cm. — (Childrens literature and culture ; 85) Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Children’s literature, English—History and criticism. 2. Imperialism in literature. 3. India—In literature. I. Title. PR990.G67 2012 820.9'9282—dc23 2011052747 ISBN13: 978-0-415-88636-9 (hbk) ISBN13: 978-0-203-11222-9 (ebk) Typeset in Minion by IBT Global. Chapter Five Trivializing Empire The Topsy-Turvy World of Upendrakishore Ray and Sukumar Ray On October 16, 1905, Lord Curzon partitioned Bengal—the cradle of British rule in India and the birthplace of the Bengali intelligentsia—by proclaiming that it was administratively prudent to divide such a populous and geographi- cally unwieldy entity into two separate states. -

Admissions Are Provisional

JADAVPUR UNIVERSITY KOLKATA – 700 032 August 6, 2019 A D M I S S I O N M.A. (DAY) COURSE IN JOURNALISM & MASS COMMUNICATION SESSION 2019 - 2021 It may please be noted that all admissions are provisional. I. The Revised Selection and Waiting Lists given below are provisional and are subject to: the fulfilling of the eligibility criteria as notified earlier. the verification of the equivalence of marks/degree from other universities to those of this university, where applicable. correction in the merit position due to any error, if any. II. If at the time of counselling/admission and verification of marks, it is found by the university authority that a student does not satisfy the eligibility criteria, and does not have completed results up to and including 5th semester (or semester up to the Final semester) or Part- I and Part-II of Honours/Major course in the relevant subject, s/he will not be considered for admission, even if he/she is provisionally selected for admission; a student has provided incorrect information in his online application form, his/her application and offer of provisional admission shall be liable to be cancelled; a student had entered incorrect marks in his/her on-line application form, his/her rank position in the selection/merit list provided below shall be revised and corrected accordingly on the basis of actual marks obtained in the examination concerned. III. SC/ST/OBC-A/OBC-B/PD quota as per State Govt. rules. IV. No separate intimation will be sent to individual candidate. Number of Seats Category Seats General 27 S.C. -

Containment Zone Preparation.Xlsx

S.No Borough Area Name Ward No. 1 1 H/22, J K Ghosh Road, Lal Maidan 3 Lal Maidan (Krishna Mallick lane & 86 Belgachia Road, J K 2 1 Ghosh Road) ,Belgachhia PS- Ultadanga 3 51/2 ANATH NATH DEB LANE, KOLKATA 700037, Anath deb 3 1 lane,Manmath ditta rd,talapark ave 3 75/A KHUDIRAM BOSE SARANI, PO BELGACHIA, PS 4 1 ULTADANGA, KOL - 37 3 13/A/6 RAJA MANINDRA ROAD, KOLKATA 37, 5, 6, 7, 8, 10, 11, 5 1 12, 13, 14 Raja Manindra Road, Rani Harshamuki Road, 4 Chandra Nath Simlai Lane 11C NORTHERN AVENUE, PAIKPARA, BELGACHIA SO, 6 1 BELGACHIA, KOLKATA 700037, 10 TO 12 UMAKANTA SEN 4 LANE, 3 TO 28 NORTHERN AVENUE 107/1B BELGACHIA ROAD,( KHUDIRAM BOSE SARANI) KOLKATA 7 1 700004, 90 to 107/1b belgachia rd,rail qtr,kolkata stn 5 jhupri,raicharan sadhukhan rd, 20/1/1 Khudiram Bose sarani, Belgachia Road, Kolkata 37, Belgachia Road, 20 Belgachia Road, Sirish Chowdhury Lane, 8 1 Nilmoni Mitra Road, Bonomali Chatterjee Lane, Tarak Bose 5 Lane, Raja Siew Box, Sashibushan Chatterjee Lane, Shyama Charan Mukherjee Lane, 9 1 32/9, B.T. Road, PS Cossipore 1 26/9 KC Road, Chiriya More, Kolkata 700002, 26/9 KHAGEN 10 1 CHATTERJEE ROAD ENTIRE BUSTEE 1 22/4/H/6 KC ROAD, COSSIPORE, KOLKATA, 22 KHAGEN 11 1 CHATTERJEE ROAD ENTIRE BUSTEE 1 96/H/22/2 Kashipur, Kolkata 33, 95, 96, 99, 100 KASHI PUR 12 1 ROAD ENTIRE BUSTEE AREA. 1 23/1, COSSIPORE ROAD, P.O- COSSIPORE, 13 1 KOLKATA 6 8 NO SETHPUKUR ROAD, KASIPUR, 1 - 9 JOGEN MUKHERJEE ROAD, BANGA SEN LANE, 1,2,3,Cossipur Rd,JagannathTemple rd 14 1 all premises , P1 Stand Bank Rd,Nawab patty all premises, 6 Turner Rd all premises,Brojodayal Shah Rd all premises, 524B, RABINDRA SARANI, P.O.- BAGBAZAR, PS: SHYAMPUKUR, 15 1 WestBengal KOLKATA 700003, 517 TO 580 RABINDRA SARANI, 8 496, RABNDRA SARANI, KOL-5, RADHAKANTA DEB LANE, LALBAGAN BUSTEE, 22/A, RAJA MANINDRA ROAD, CHITPUR, KOLKATA-37, 22 16 1 RAJA MONINDRA ROAD ENTIRE SLUM 4 S.No Borough Area Name Ward No. -

Indina Journal of Comparative Literature and Trandslation Studies

ISSN: 2321-8274 INDINA JOURNAL OF COMPARATIVE LITERATURE AND TRANDSLATION STUDIES VOLUME 1, NUMBER 2 DECEMBER 2013 LITERATURE, ART AND PERFORMANCE EDITORS MRINMOY PRAMANICK MD. INTAJ ALI IJCLTS is an Online Open Access Journal of Comparative Literature and Translation Studies Published By Mrinmoy Pramanick And Md. Intaj Ali Published on: 30th March, 2014 Journal URL: http://ijclts.wordpress.com/ @All the Copy Rights reserved to the Editors, IJCLTS Advisory Committee 1. Prof. Avadhesh K Singh, Director, School of Translation Studies and Training, Indira Gandhi National Open University, New Delhi, India 2. Prof. Tutun Mukherjee, Professor, Centre for Comparative Literature, School of Humanities, University of Hyderabad, India 3.Nikhila H, M.A., Ph.D. (Bangalore), Associate Professor, Department Of Film Studies And Visual Communication, EFLU, Hyderabad, India 4. Tharakeshwar, V.B, Head & Associate Professor, Department of Translation Studies, School of Interdisciplinary Studies, EFLU, Hyderabad, India Editorial Board Co-Editors: 1. Saswati Saha, ICSSR Doctoral Fellow, Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Calcutta, India 2. Rindon Kundu, Research Scholar, Centre for Applied Linguistics and Translation Studies, University of Hyderabad, India 3. Nisha Kutty, Centre for Comparative Literature, University of Hyderabad, India Board of Editors: (Board of Editors includes Editors and Co-Editors) -Dr. Ami U Upadhyay, Professor of English, Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Open University, Ahamedabad, India - Dr. Rabindranath Sarma, Associate Professor, Centre for Tribal Folk Lore, Language and Literature, Central University of Jharkhand, India -Dr. Sushumna Kannan, PhD in Cultural Studies Centre for the Study of Culture and Society, Bangalore, Adjunct Faculty, Department of Women’s Studies, San Diego State University -Dr. -

Golam Murshad-All Book Script

Reluctant Debutante: Response of Bengali Women to Modernisation, 1849-1905 G. Murshid Rajshahi : Sahitya Samsad, Rajshahi University 1983 ______________________________________________________________Preface This book is a modest study of how a section of English educated Bengali men exposed their women to the process of modernization during the late nineteenth century and how women responded to these male efforts. It also gives an evaluation of how far some Bengali women were modernized as a result of the male initiated reform movement. While a number of books on how social reformers such as Rammohan Roy, Iswar Chandra Bidyasagar, Akshay Kumar Datta, Keshab Chandra Sen and Dwarkanth Ganguli contributed to the elevation of the downtrodden Bengali women have been published, no one has tried to give an account of how women themselves responded to modernization. This book seeks particularly to throw some light on this aspect, so long neglected. I am grateful to the University of Melbourne for giving me a post-doctoral research fellowship for two years (1978-1980) as well as for giving a grant for securing research material from overseas. I appreciate the help of Professor Sibnarayan Ray under whose supervision I did my research. He helped me in clarifying my ideas. I am very much indebted to Professor David Kopf, Dr Marian Maddern, Dr Ellen McEwan and Dr Meredith Borthwick for reading the manuscript and for suggesting improvements. I am also grateful to James Wise, Patrick Wolfe, Professor Joan Hussein, Ali Anwar and Pauline Rule for their valuable suggestions. I am extremely grateful to the Ford Foundation, Dacca, for giving me a generous grant, which covered almost the entire cost of publishing the first edition of this book.