Golam Murshad-All Book Script

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter-8 Clothing : a Social History

Chapter-8 Clothing : A Social History 1 marks Questions 1. What does ermine stands for? Ans. it’s a type of fur. 2. Sans Culottes stands for what? Ans. Without Knee breaches. 3. Who was William Hogarth? Ans. He was an English painter. 4. What does busk mean? Ans. It means strips of wood and steel 5. Who was Marry Somerville? Ans. She was a Mathematician 6. Who was John Keats? Ans. English Poet 7. Who is the writer of the novel ‘Vanity Fair’? Ans. John Keats. 8. In which year the Rational Dress Society was founded in England? Ans. It was founded in 1889. 9. Which war had changed the women’s clothing? Ans. First World War. 10. When was Western Style clothing introduced in India? Ans. 19th century. 11. What does the phenta means? Ans. It means Hat. 12. Who was Verrier Elwin? Ans. Anthropologist. 13. When did Slavery abolished in Travancore? Ans. 1855. 14. Who was Dewan of Mysore state from 1912 to 1918? Ans. M. Visveswaraya. 15. Who was Governor-General of India between the years 1824-28? Ans. Amherst. 16. Name the person who refused to take off shoes in the court of session Judge. Ans. Manockjee Cowasjee Entee. 17. Who was first Indian ICS officer? Ans. Satyendranath. 18. Name the autobiography of C. Kesvan? Ans. Jeevita Samram. 19. In which year M.K. Gandhi went to London for higher study? Ans. 1888. 20. When did Mahatma Gandhi return back to India? Ans. 1915. 3 marks Questions 1. State any three reasons why khadi was important to Mahatma Gandhi? Ans. -

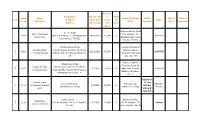

Comp. Sl. No Name S/D/W/O Designation & Office Address Date of First Application (Receving) Basic Pay / Pay in Pay Band Type

Basic Pay Designation Date of First / Type Comp. Name Name & Address Roster Date of Date of Sl. No. & Office Application Pay in of Status Sl. No S/D/W/O D.D.O. Category Birth Retirement Address (Receving) Pay Flat Band Accounts Officer, 9D & Gr. - II Sister Smt. Anita Biswas B.G. Hospital , 57, 1 1879 9D & B.G. Hospital , 57, Beleghata Main 28/12/2012 21,140 A ALLOTTED Sri Salil Dey Beleghata Main Road, Road, Kolkata - 700 010 Kolkata - 700 010 District Fishery Officer Assistant Director of Bikash Mandal O/O the Deputy Director of Fisheries, Fisheries, Kolkata 2 1891 31/12/2012 22,500 A ALLOTTED Lt. Joydev Mandal Kolkata Zone, 9A, Esplanade East, Kol - Zone, 9A, Esplanade 69 East , Kol - 69 Asstt. Director of Fishery Extn. Officer Fisheries, South 24 Swapan Kr. Saha O/O The Asstt. Director of Fisheries 3 1907 1/1/2013 17,020 A Pgns. New Treasury ALLOTTED Lt. Basanta Saha South 24 Pgs., Alipore, New Treasury Building (6th Floor), Building (6th Floor), Kol - 27 Kol - 27 Eligible for Samapti Garai 'A' Type Assistant Professor Principal, Lady Allotted '' 4 1915 Sri Narayan Chandra 2/1/2013 20,970 A flats but Lady Brabourne College Brabourne College B'' Type Garai willing 'B' Type Flat Staff Nurse Gr. - II Accounts Officer, Lipika Saha 5 1930 S.S.K.M. Hospital , 244, A.J.C. Bose Rd. , 4/1/2013 16,380 A S.S.K.M. Hospital , 244, Allotted Sanjit Kumar Saha Kol -20 A.J.C. Bose Rd. , Kol -20 Basic Pay Designation Date of First / Type Comp. -

Rabindranath Tagore: a Social Thinker and an Activist a Review of Literature and a Bibliography Kumkum Chattopadhyay, Retd

2018 Heritage Vol.-V Rabindranath Tagore: a Social Thinker and an Activist A Review of Literature and a Bibliography Kumkum Chattopadhyay, Retd. Associate Professor, Dept. of Political Science, Bethune College, Kolkata-6 Abstract: Rabindranath Tagore, although basically a poet, had a multifaceted personality. Among his various activities his sincerity as a social thinker and activist attract our attention. But this area is till now comparatively unexplored. Many scholars in this area have tried to study Tagore as a social thinker. But so far the findings are scattered and on the whole there is no comprehensive analysis in the strict sense of the term. Hence it is necessary to collect the different findings and to integrate and arrange them within a theoretical framework. This article is an attempt to make a review of literature of the existing books and to prepare a short but sharp bibliography to introduce the area. Key words: Rabindranath Tagore, society, social, political, history, education, Santiniketan, Visva-Bharati Rabindranath Tagore (1861 – 1941) was a prolific writer, a successful music composer, a painter, an actor, a drama director and what not. Besides these talents, he was also a social activist and contributed a lot to Indian social and political thought, although this area has not been very much explored till now. Tagore was emphatic upon society building. So he tried to develop all the component elements which were essential for developing the Indian society. He studied the history of India to follow the trend of its evolution. Next he prepared his programme of action – rural reconstruction and spread of education. -

Courses Taught at Both the Undergraduate and the Postgraduate Levels

Jadavpur University Faculty of Arts Department of History SYLLABUS Preface The Department of History, Jadavpur University, was born in August 1956 because of the Special Importance Attached to History by the National Council of Education. The necessity for reconstructing the history of humankind with special reference to India‘s glorious past was highlighted by the National Council in keeping with the traditions of this organization. The subsequent history of the Department shows that this centre of historical studies has played an important role in many areas of historical knowledge and fundamental research. As one of the best centres of historical studies in the country, the Department updates and revises its syllabi at regular intervals. It was revised last in 2008 and is again being revised in 2011.The syllabi that feature in this booklet have been updated recently in keeping with the guidelines mentioned in the booklet circulated by the UGC on ‗Model Curriculum‘. The course contents of a number of papers at both the Undergraduate and Postgraduate levels have been restructured to incorporate recent developments - political and economic - of many regions or countries as well as the trends in recent historiography. To cite just a single instance, as part of this endeavour, the Department now offers new special papers like ‗Social History of Modern India‘ and ‗History of Science and Technology‘ at the Postgraduate level. The Department is the first in Eastern India and among the few in the country, to introduce a full-scale specialization on the ‗Social History of Science and Technology‘. The Department recently qualified for SAP. -

IP Tagore Issue

Vol 24 No. 2/2010 ISSN 0970 5074 IndiaVOL 24 NO. 2/2010 Perspectives Six zoomorphic forms in a line, exhibited in Paris, 1930 Editor Navdeep Suri Guest Editor Udaya Narayana Singh Director, Rabindra Bhavana, Visva-Bharati Assistant Editor Neelu Rohra India Perspectives is published in Arabic, Bahasa Indonesia, Bengali, English, French, German, Hindi, Italian, Pashto, Persian, Portuguese, Russian, Sinhala, Spanish, Tamil and Urdu. Views expressed in the articles are those of the contributors and not necessarily of India Perspectives. All original articles, other than reprints published in India Perspectives, may be freely reproduced with acknowledgement. Editorial contributions and letters should be addressed to the Editor, India Perspectives, 140 ‘A’ Wing, Shastri Bhawan, New Delhi-110001. Telephones: +91-11-23389471, 23388873, Fax: +91-11-23385549 E-mail: [email protected], Website: http://www.meaindia.nic.in For obtaining a copy of India Perspectives, please contact the Indian Diplomatic Mission in your country. This edition is published for the Ministry of External Affairs, New Delhi by Navdeep Suri, Joint Secretary, Public Diplomacy Division. Designed and printed by Ajanta Offset & Packagings Ltd., Delhi-110052. (1861-1941) Editorial In this Special Issue we pay tribute to one of India’s greatest sons As a philosopher, Tagore sought to balance his passion for – Rabindranath Tagore. As the world gets ready to celebrate India’s freedom struggle with his belief in universal humanism the 150th year of Tagore, India Perspectives takes the lead in and his apprehensions about the excesses of nationalism. He putting together a collection of essays that will give our readers could relinquish his knighthood to protest against the barbarism a unique insight into the myriad facets of this truly remarkable of the Jallianwala Bagh massacre in Amritsar in 1919. -

Landscaping India: from Colony to Postcolony

Syracuse University SURFACE English - Dissertations College of Arts and Sciences 8-2013 Landscaping India: From Colony to Postcolony Sandeep Banerjee Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/eng_etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, Geography Commons, and the South and Southeast Asian Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Banerjee, Sandeep, "Landscaping India: From Colony to Postcolony" (2013). English - Dissertations. 65. https://surface.syr.edu/eng_etd/65 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts and Sciences at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in English - Dissertations by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT Landscaping India investigates the use of landscapes in colonial and anti-colonial representations of India from the mid-nineteenth to the early-twentieth centuries. It examines literary and cultural texts in addition to, and along with, “non-literary” documents such as departmental and census reports published by the British Indian government, popular geography texts and text-books, travel guides, private journals, and newspaper reportage to develop a wider interpretative context for literary and cultural analysis of colonialism in South Asia. Drawing of materialist theorizations of “landscape” developed in the disciplines of geography, literary and cultural studies, and art history, Landscaping India examines the colonial landscape as a product of colonial hegemony, as well as a process of constructing, maintaining and challenging it. In so doing, it illuminates the conditions of possibility for, and the historico-geographical processes that structure, the production of the Indian nation. -

Postcoloniality, Science Fiction and India Suparno Banerjee Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, Banerjee [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2010 Other tomorrows: postcoloniality, science fiction and India Suparno Banerjee Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Banerjee, Suparno, "Other tomorrows: postcoloniality, science fiction and India" (2010). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3181. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3181 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. OTHER TOMORROWS: POSTCOLONIALITY, SCIENCE FICTION AND INDIA A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In The Department of English By Suparno Banerjee B. A., Visva-Bharati University, Santiniketan, West Bengal, India, 2000 M. A., Visva-Bharati University, Santiniketan, West Bengal, India, 2002 August 2010 ©Copyright 2010 Suparno Banerjee All Rights Reserved ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My dissertation would not have been possible without the constant support of my professors, peers, friends and family. Both my supervisors, Dr. Pallavi Rastogi and Dr. Carl Freedman, guided the committee proficiently and helped me maintain a steady progress towards completion. Dr. Rastogi provided useful insights into the field of postcolonial studies, while Dr. Freedman shared his invaluable knowledge of science fiction. Without Dr. Robin Roberts I would not have become aware of the immensely powerful tradition of feminist science fiction. -

Reflections of Bengali Subaltern Society and Cultural Identity Through the Bangali Bhadrolok’S Lenses: an Analysis

Parishodh Journal ISSN NO:2347-6648 Reflections Of Bengali Subaltern Society And Cultural IdentIty through the BangalI Bhadrolok’s lenses: an Analysis -Mithun Majumder Phd Research scholar, Deptt of International Relations, Jadavpur University Abstract The Bengalis are identified as culture savvy race, at the national and international levels. But if one dwells deep into Bengali culture, one may identify an admixture of elite/ higher class culture with typical lower/subaltern class culture. Often, it has been witnessed that elite/upper class culture has influenced subaltern class culture. This essay attempts to analyze such issues like: How is the position of the subaltern class reflected in typical elite class mindset? How do they define the subaltern class? Is Bengali culture dominated by the elite class only or the subaltern class gets priority as the chief producer class? This essay strives to answer many such questions Key Words: Bhadralok, Subalterns, Culture, Class, Race, JanaJati By Bengali society and cultural identity, one does mean the construction of a typical Bhadralok cultural identity and Kolkata is identified as the epicentre of Bengali Bhadralok culture. But the educated middle class city residents, salaried people, intellectuals also represent this culture. Bengali art and literature and the ideas generated from the civil society in Kolkata and its cultural exchanges with typical Mofussil or rural subaltern culture can lead to the construction of new language or dialect and may even lead to deconstruction of the same. The unorganized rural women labourers(mostly working as domestic help) often use the phrase that “ we work in Baboo homes in Kolkata”. -

Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan Title Accno Language Author / Script Folios DVD Remarks

www.ignca.gov.in Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan Title AccNo Language Author / Script Folios DVD Remarks CF, All letters to A 1 Bengali Many Others 75 RBVB_042 Rabindranath Tagore Vol-A, Corrected, English tr. A Flight of Wild Geese 66 English Typed 112 RBVB_006 By K.C. Sen A Flight of Wild Geese 338 English Typed 107 RBVB_024 Vol-A A poems by Dwijendranath to Satyendranath and Dwijendranath Jyotirindranath while 431(B) Bengali Tagore and 118 RBVB_033 Vol-A, presenting a copy of Printed Swapnaprayana to them A poems in English ('This 397(xiv Rabindranath English 1 RBVB_029 Vol-A, great utterance...') ) Tagore A song from Tapati and Rabindranath 397(ix) Bengali 1.5 RBVB_029 Vol-A, stage directions Tagore A. Perumal Collection 214 English A. Perumal ? 102 RBVB_101 CF, All letters to AA 83 Bengali Many others 14 RBVB_043 Rabindranath Tagore Aakas Pradeep 466 Bengali Rabindranath 61 RBVB_036 Vol-A, Tagore and 1 www.ignca.gov.in Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan Title AccNo Language Author / Script Folios DVD Remarks Sudhir Chandra Kar Aakas Pradeep, Chitra- Bichitra, Nabajatak, Sudhir Vol-A, corrected by 263 Bengali 40 RBVB_018 Parisesh, Prahasinee, Chandra Kar Rabindranath Tagore Sanai, and others Indira Devi Bengali & Choudhurani, Aamar Katha 409 73 RBVB_029 Vol-A, English Unknown, & printed Indira Devi Aanarkali 401(A) Bengali Choudhurani 37 RBVB_029 Vol-A, & Unknown Indira Devi Aanarkali 401(B) Bengali Choudhurani 72 RBVB_029 Vol-A, & Unknown Aarogya, Geetabitan, 262 Bengali Sudhir 72 RBVB_018 Vol-A, corrected by Chhelebele-fef. Rabindra- Chandra -

Setting the Stage: a Materialist Semiotic Analysis Of

SETTING THE STAGE: A MATERIALIST SEMIOTIC ANALYSIS OF CONTEMPORARY BENGALI GROUP THEATRE FROM KOLKATA, INDIA by ARNAB BANERJI (Under the Direction of Farley Richmond) ABSTRACT This dissertation studies select performance examples from various group theatre companies in Kolkata, India during a fieldwork conducted in Kolkata between August 2012 and July 2013 using the materialist semiotic performance analysis. Research into Bengali group theatre has overlooked the effect of the conditions of production and reception on meaning making in theatre. Extant research focuses on the history of the group theatre, individuals, groups, and the socially conscious and political nature of this theatre. The unique nature of this theatre culture (or any other theatre culture) can only be understood fully if the conditions within which such theatre is produced and received studied along with the performance event itself. This dissertation is an attempt to fill this lacuna in Bengali group theatre scholarship. Materialist semiotic performance analysis serves as the theoretical framework for this study. The materialist semiotic performance analysis is a theoretical tool that examines the theatre event by locating it within definite material conditions of production and reception like organization, funding, training, availability of spaces and the public discourse on theatre. The data presented in this dissertation was gathered in Kolkata using: auto-ethnography, participant observation, sample survey, and archival research. The conditions of production and reception are each examined and presented in isolation followed by case studies. The case studies bring the elements studied in the preceding section together to demonstrate how they function together in a performance event. The studies represent the vast array of theatre in Kolkata and allow the findings from the second part of the dissertation to be tested across a variety of conditions of production and reception. -

The Black Hole of Empire

Th e Black Hole of Empire Th e Black Hole of Empire History of a Global Practice of Power Partha Chatterjee Princeton University Press Princeton and Oxford Copyright © 2012 by Princeton University Press Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to Permissions, Princeton University Press Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540 In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW press.princeton.edu All Rights Reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Chatterjee, Partha, 1947- Th e black hole of empire : history of a global practice of power / Partha Chatterjee. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-691-15200-4 (hardcover : alk. paper)— ISBN 978-0-691-15201-1 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Bengal (India)—Colonization—History—18th century. 2. Black Hole Incident, Calcutta, India, 1756. 3. East India Company—History—18th century. 4. Imperialism—History. 5. Europe—Colonies—History. I. Title. DS465.C53 2011 954'.14029—dc23 2011028355 British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available Th is book has been composed in Adobe Caslon Pro Printed on acid-free paper. ∞ Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 To the amazing surgeons and physicians who have kept me alive and working This page intentionally left blank Contents List of Illustrations ix Preface xi Chapter One Outrage in Calcutta 1 Th e Travels of a Monument—Old Fort William—A New Nawab—Th e Fall -

1St Cover Oct 2017 Issue.Indd

FEATURE ARTICLE Asima Chatterjee First Woman DSc of India A Tribute on her DHRUBAJYOTI CHATTOPADHYAY Birth Centenary HERE was a time when social and cultural taboos kept away Twomen from scientifi c research; it was traditionally preserved for men for a long period throughout the world. Only a few women could manage to establish themselves due to their strong will and passion for science. Asima Chatterjee was one of such woman scientist of India. She was the first woman to be awarded the Doctorate of Science (DSc) degree by an Indian University; fi rst woman scientist to occupy a Chair in Calcutta university, fi rst woman General President of the Indian Science Congress and also fi rst woman awarded the Shanti Swaroop Bhatnagar award in Science. Her research career spanned over six decades. Her major interest was in the chemistry of natural products from Indian Medicinal Plants. Born on 23 September 1917 in Kolkata, West Bengal, since her childhood Asima Chatterjee was interested in medicinal fl ora and the use of these medicinal plants to treat Asima was a meritorious student. of Calcutta – Nawab Latiff and Father diseases. She felt the urge to introduce After passing her Matriculation Lafnot – along with the Hemprova Bose it in modern medical system and Examination in 1932 she secured the Memorial Medal. devoted her life to separate the chemical Bengal Government Scholarship. In She eagerly wanted to get admission components of plants and other living 1934, she passed the ISc Examination to chemistry honours to explore the organisms, including those of marine from the Bethune College and again science behind Indian traditional sources, followed by elucidation of obtained the Bengal Government medicinal plants but at that time there their molecular structure, which was Scholarship.