International Libel and Privacy Handbook

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

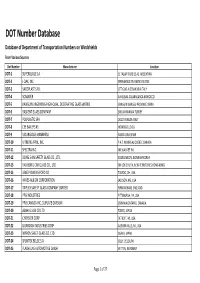

DOT Number Database Database of Department of Transportation Numbers on Windshields from Various Sources Dot Number Manufacturer Location DOT‐1 SUPERGLASS S.A

DOT Number Database Database of Department of Transportation Numbers on Windshields From Various Sources Dot Number Manufacturer Location DOT‐1 SUPERGLASS S.A. EL TALAR TIGRE BS.AS. ARGENTINA DOT‐2 J‐DAK, INC. SPRINGFIELD TN UNITED STATES DOT‐3 SACOPLAST S.R.L. OTTIGLIO ALESSANDRIA ITALY DOT‐4 SOMAVER AIN SEBAA CASABNLANCA MOROCCO DOT‐5 JIANGUIN JINGEHENG HIGH‐QUAL. DECORATING GLASS WORKS JIANGUIN JIANGSU PROVINCE CHINA DOT‐6 BASKENT GLASS COMPANY SINCAN ANKARA TURKEY DOT‐7 POLPLASTIC SPA DOLO VENEZIA ITALY DOT‐8 CEE BAILEYS #1 MONTEBELLO CA DOT‐9 VIDURGLASS MANBRESA BARCELONA SPAIN DOT‐10 VITRERIE APRIL, INC. P.A.T. MONREAL QUEBEC CANADA DOT‐11 SPECTRA INC. MILWAUKEE WI DOT‐12 DONG SHIN SAFETY GLASS CO., LTD. BOOKILMEON, JEONNAM KOREA DOT‐13 YAU BONG CAR GLASS CO., LTD. ON LOK CHUEN, NEW TERRITORIES HONG KONG DOT‐15 LIBBEY‐OWENS‐FORD CO TOLEDO, OH, USA DOT‐16 HAYES‐ALBION CORPORATION JACKSON, MS, USA DOT‐17 TRIPLEX SAFETY GLASS COMPANY LIMITED BIRMINGHAM, ENGLAND DOT‐18 PPG INDUSTRIES PITTSBURGH, PA, USA DOT‐19 PPG CANADA INC.,DUPLATE DIVISION OSHAWA,ONTARIO, CANADA DOT‐20 ASAHI GLASS CO LTD TOKYO, JAPAN DOT‐21 CHRYSLER CORP DETROIT, MI, USA DOT‐22 GUARDIAN INDUSTRIES CORP AUBURN HILLS, MI, USA DOT‐23 NIPPON SHEET GLASS CO. LTD OSAKA, JAPAN DOT‐24 SPLINTEX BELGE S.A. GILLY, BELGIUM DOT‐25 FLACHGLAS AUTOMOTIVE GmbH WITTEN, GERMANY Page 1 of 27 Dot Number Manufacturer Location DOT‐26 CORNING GLASS WORKS CORNING, NY, USA DOT‐27 SEKURIT SAINT‐GOBAIN DEUTSCHLAND GMBH GERMANY DOT‐32 GLACERIES REUNIES S.A. BELGIUM DOT‐33 LAMINATED GLASS CORPORATION DETROIT, MI, USA DOT‐35 PREMIER AUTOGLASS CORPORATION LANCASTER, OH, USA DOT‐36 SOCIETA ITALIANA VETRO S.P.A. -

December 2016 (75)

THE OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE CALIFORNIA THE OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE CALIFORNIA ASSOCIATION OF ACCIDENT RECONSTRUCTION SPECIALISTS ASSOCIATION OF ACCIDENT RECONSTRUCTIONTHE OFFICIAL SPECIALISTS PUBLICATION OF THE C ASSOCIATION OF ACCIDENT RECONSTRUCTION SPECIALISTS ! changes best not taken for granted retrospective of automotive and traffic heroes A Volume 18, Number 4 December 2016 CA2RS.com BOARD BEAT te As I reflect on 2016, I realize the CA2RS organization had another very successful year in many ways! First, in the area of training—arguably the organization’s most important mission—we had a very productive year. Our three quarterly training sessions saw new topics introduced and discussed. The attendance at the quarterly trainings this year, both in Northern and Southern California, was higher than ever. This tells me two things: we are offering interesting training to the membership and the membership is more involved than in past years. This increased involvement by the membership is encouraging to me and the other members of the BOD. The Annual Conference, held this year in South Lake Tahoe, also had greater attendance that we have seen in recent years. Probably the most exciting and memorable event of 2016 was CA2RS participation and involvement in WREX 2016 in May. The WREX Conference was the largest conference ever held in the field of accident investigation and reconstruction with over 800 people in attendance from all over the world. Many people in attendance at the WREX Conference, including folks who have attended several conferences in our field over the years, stated it was the best Conference they had ever attended. -

STYLING Vs. SAFETY the American Automobile Industry and the Development of Automotive Safety, 1900-1966 Joel W

STYLING vs. SAFETY The American Automobile Industry and the Development of Automotive Safety, 1900-1966 Joel W. Eastm'm STYLING vs. SAFETY The American Automobile Industry and the Development of Automotive Safety, 1900-1966 Joel W. Eastman UNIVERSITY PRESS OF AMERICA LANHAM • NEW YORK • LONDON Copyright © 1984 by University Press of America," Inc. 4720 Boston Way Lanham. MD 20706 3 Henrietta Street London WC2E 8LU England All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Eastman, Joel W., 1939– Styling vs. safety. Originally presented as author's thesis (doctoral– University of Florida) Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. Automobiles–Safety measures–History. I. Title. 11. Title: Styling versus safety. TL242.E24 1984 363.1'25'0973 83-21859 ISBN 0-8191-3685-9 (alk. paper) ISBN 0-8191-3686-7 (pbk. : alk. paper) All University Press of America books are produced on acid-free paper which exceeds the minimum standards set by the National Historical Publications and Records Commission. Dedicated to Claire L. Straith, Hugh DeHaven and all of the other pioneers of automotive safety iii iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS No research project is entirely the work of one person, and such is the case with this study which would not have been possible without the cooperation and assistance of scores of people. I would like to express my appreciation to those who agreed to be interviewed in person or on the telephone, allowed me to examine their personal papers, and answered questions and forwarded materials through the mail. I utilized the resources of numerous libraries and archives, but a few deserve special mention. -

Motor Show - Earls Court 1954

MOTOR SHOW - EARLS COURT 1954 r SUMMARY OF NEW PRODUCTS AND OTHER EXHIBITS OF SPECIAL INTEREST which have been notified to the Press Department of the Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders at the time of going to press. This list does not purport to be complete, and the details, before being quoted, should be confirmed with the Exhibitors concerned. FOR A FULL LIST OF EXHIBITORS AND OF PRODUCTS SEE THE OFFICIAL CATALOGUE "NS" = New, introduced at the Show. "NR" = New, introduced recently CAR SECTION Stand Nos. Exhibitors. Remarks. 139 A.C. CARS LTD. "Ace" sports car with re designed body (N.R. 29/4/54) 121 A.F.N. LTD. Frazer Nash "Sebring" (N.R. 16/7/54). Frazer Nash 2-litre Le Mans model. 114 ALLARD MOTOR CO., LTD. 2i litre coachbuilt ,_2 str. saloon on Palm Beach chassis (N.S. 20/10/54). 128 ALVIS LTD. "TO 21/100" coupe. 169 ARMSTRONG SIDDELEY MOTORS "Sapphire" with 2 pedal control, LTD. fully automatic gearbox (N.R. 1/10/54). 124 ASTON MARTIN LTD. "DB2-4" sports saloon and drop- head coupe with new 3-litre engine, saloon and drophead coupe (N.R. 25/8/54) and DB3 production version of racing car (N.R. 30/9/54). r*bh AUSTIN MOTOR CO..LTD. "Cambridge" A40/A50 (N.R. 28/9/54). "Westminster" A90 saloon (N. S. 19/10/54). 1 50a AUTO UNION G.m.b.H. DKW "Sonderklasse". 171 BE NT LEY MOTORS (1931) LTD. "Continental" sports saloon and "Continental" drophead coupe by Park Ward (N.R. -

Libbey-Owens-Ford Glass Company Records, 1851-1991

The Ward M. Canaday Center for Special Collections The University of Toledo Finding Aid Libbey-Owens-Ford Glass Company Records, 1851-1991 MSS-066 Size: 88 linear ft. Provenance: Received from Libbey-Owens-Ford Company in 1987, 1988, 1989, 1992, 1996, and 1998. Access: OPEN Collection Summary: This large collection of corporate records includes materials ranging from formal board of directors' minutes to personal photos of individuals involved with the company's history. Administrative records include corporate record books from LOF and its predecessors: Edward Ford Plate Glass Company (1899-1930), Toledo Glass Company (1895-1931), Libbey- Owens Glass Company (1916-1933), and subsidiaries. Annual reports from LOF Glass Company (1930-1982) and the Pilkington Group (1988-) provide summaries of corporate activities. Corporate file records (1895-1958) deal primarily with contracts, subsidiaries, and notably a government anti-trust investigation of LOF (1930-1948). Publications, speeches, and reports created by LOF employees and others include manuscripts and research notes from two company-sponsored corporate histories, corporate newsletters (1939-1980), and general glass industry materials. The single largest series in the collection focuses on sales and promotion. There are files on 50 distributors and dealers of LOF products across the U.S. (1930s-1970s), press releases (1946-1984), and advertising yearbooks and scrapbooks (1851-1977). "Glass at Work" files serve as a valuable source of information on the actual uses of LOF products, as well as the advertising department's use of "real life" applications for promotional purposes. They include files on glazing in everything from airports to homes (1945-1986). Subjects: Architecture, Business and Commerce and Education and Schools. -

OFFICIAL Q a L CATALOGUE

Patron: HER MAJESTY THE QUEEN OFFICIAL QAl CATALOGUE £ D [11 special issues of Britain's leading motoring journal The AUTOCAR'S magnificent Show Numbers give you the world's finest coverage of this great event—from advance A better buy guide and preview to because it's complete stand-by-stand report and expert summing-up better built! of trends for 1960. Superbly illustrated with hundreds of photographs and technical drawings. SHOW GUIDE (16 Oct.) Is. Treble-sized SHOW REPORT (23 Oct.) 2s. 6d. The J^Ak4ZAWUtAl(i new SHOW REVIEW (30 Oct.) Is. Hillman Minx Stand 22 - i 'Uisr • ''• MOOTS* MOTORS IIWITIO AUTOMOBILE ENGINEER Only British journal catering solely for automobile designers and manufacturers. Month by month, it covers the latest developments and methods in design, production, materials, and works practice and equipment. Monthly 3s 6d ILIFFE & SONS LTD. DORSET HOUSE STAMFORD STREET LONDON SE1 WATERLOO 3333 (65 lines) [3] PATRON: Her Majesty THE QUEEN 2I"-31" OCTOBER 1959 EARLS COURT UNDER THE ORGANISATION OF The Society of Motor Manufacturers & Traders, Ltd, President: J. M. A. SMITH Deputy President: A. R. M. GEDDES, O.B.E. Vice-Presidents: M. A. H. BELLHOUSE, M. L. BREEDEN Hon. Treasurer: THE HON. GEOFFREY ROOTES MOTOR EXHIBITION COMMITTEE Chairman: MORTIMORE, H. BATTY, W. B. ROOTES, THE LORD, G.B.E. BEHARRELL, G. E. DIXON, G. LLOYD SANGSTER, T. BELLHOUSE, M. A. H. FODEN, J. E. SHIRLEY, J. W. BLACK, SIR WILLIAM Fox, E. R. SMITH, DR. F. LLEWELLYN BRADBURY, L. J. FULLER, A. B. SMITH, J. M. A. BRADSTOCK, MAIOR G., GARDNER, C. -

576644 5337.Pdf

Case 10-31607 Doc 5337 Filed 05/25/16 Entered 05/25/16 09:17:54 Desc Main Document Page 1 of 238 Case 10-31607 Doc 5337 Filed 05/25/16 Entered 05/25/16 09:17:54 Desc Main Document Page 2 of 238 Garlock SealingCase Technologies 10-31607 LLC, et al. Doc - U.S. 5337 Mail Filed 05/25/16 Entered 05/25/16 09:17:54 Desc MainServed 5/23/2016 Document Page 3 of 238 120 EAST AVENUE, LLC 3M CO. 3M COMPANY 120 EAST AVENUE, SUITE 185 FKA MINNESOTA MINING & MANUFACTURING CO. 3M EAMD CUSTOMER SERVICE ROCHESTER, NY 14607 ATTN: OFFICER AND/OR MANAGING AGENT BLDG 504-1-01 3M CORPORATE HEADQUARTERS 3M CENTER SAINT PAUL, MN 55144 ST. PAUL, MN 55144 84 LUMBER CO. A A C CONTRACTING INC A C & R INSULATION CO., INC. ATTN: OFFICER AND/OR MANAGING AGENT 175 HUMBOLDT ST 7085 DORSEY RUN RD. 1019 ROUTE 519 STE. 200 ELKRIDGE, MD 21075 EIGHTY FOUR, PA 15330 ROCHESTER, NY 14610 A C C RESOURCES CO LP A H EVANS A PATRICIA KEMP ONE MAYNARD DRIVE 6915 BLANDFORD LANE 1355 HOLLOWAY DR PARK RIDGE, NJ 07656 HOUSTON, TX 77055 PETERBOROUGH ON K9J 6G1 CA A&I CORPORATION ASBESTOS BODILY INJURY T A. COTTON WRIGHT A.B. CHANCE COMPANY VERUS CLAIMS SERVICES GRIER FURR & CRISP, PA C/O CT CORPORATION SYSTEM 2000 LENOX DRIVE 101 NORTH TRYON ST., SUITE 1240 1635 MARKET STREET SUITE 206 CHARLOTTE, NC 28246 PHILADELPHIA, PA 19103 LAWRENCEVILLE, NJ 08648 A.F. HOLMAN BOILER WORKS, INC. A.J. -

EXHIBIT a Garlock Sealingcase Technologies 10-31607 LLC, Et Al

Case 10-31607 Doc 4335 Filed 01/22/15 Entered 01/22/15 17:34:44 Desc Main Document Page 1 of 156 Case 10-31607 Doc 4335 Filed 01/22/15 Entered 01/22/15 17:34:44 Desc Main Document Page 2 of 156 EXHIBIT A Garlock SealingCase Technologies 10-31607 LLC, et al. Doc - U.S. 4335 Mail Filed 01/22/15 Entered 01/22/15 17:34:44 Desc MainServed 1/20/2015 Document Page 3 of 156 120 EAST AVENUE, LLC 3M CO. 3M COMPANY 120 EAST AVENUE, SUITE 185 FKA MINNESOTA MINING & MANUFACTURING CO. 3M EAMD CUSTOMER SERVICE ROCHESTER, NY 14607 ATTN: OFFICER AND/OR MANAGING AGENT BLDG 504-1-01 3M CORPORATE HEADQUARTERS SAINT PAUL, MN 55144 3M CENTER ST. PAUL, MN 55144 84 LUMBER CO. A A C CONTRACTING INC A C & R INSULATION CO., INC. ATTN: OFFICER AND/OR MANAGING AGENT 175 HUMBOLDT ST 7085 DORSEY RUN RD. 1019 ROUTE 519 STE. 200 ELKRIDGE, MD 21075 EIGHTY FOUR, PA 15330 ROCHESTER, NY 14610 A C C RESOURCES CO LP A H EVANS A&I CORPORATION ASBESTOS BODILY INJURY T ONE MAYNARD DRIVE 6915 BLANDFORD LANE VERUS CLAIMS SERVICES PARK RIDGE, NJ 07656 HOUSTON, TX 77055 2000 LENOX DRIVE SUITE 206 LAWRENCEVILLE, NJ 08648 A.B. CHANCE COMPANY A.F. HOLMAN BOILER WORKS, INC. A.J. BAXTER CO. C/O CT CORPORATION SYSTEM DALLAS CORPORATE OFFICE 10171 W JEFFERSON AVE 1635 MARKET STREET 1956 SINGLETON BOULEVARD RIVER ROUGE , MI 48218 PHILADELPHIA, PA 19103 DALLAS, TX 75212 A.J. BAXTER CO. A.L. -

Case 10-31607 Doc 5709 Filed 02/21/17

Case 10-31607 Doc 5709 Filed 02/21/17 Entered 02/21/17 16:25:20 Desc Main Document Page 1 of 232 Case 10-31607 Doc 5709 Filed 02/21/17 Entered 02/21/17 16:25:20 Desc Main Document Page 2 of 232 EXHIBIT A Garlock SealingCase Technologies 10-31607 LLC, et al. Doc - U.S. 5709 Mail Filed 02/21/17 Entered 02/21/17 16:25:20 Desc MainServed 2/10/2017 Document Page 3 of 232 3M CO. 84 LUMBER CO. A C & R INSULATION CO., INC. FKA MINNESOTA MINING & MANUFACTURING CO. ATTN: OFFICER AND/OR MANAGING AGENT 7085 DORSEY RUN RD. ATTN: OFFICER AND/OR MANAGING AGENT 1019 ROUTE 519 ELKRIDGE, MD 21075 3M CORPORATE HEADQUARTERS 3M CENTER EIGHTY FOUR, PA 15330 ST. PAUL, MN 55144-1000 A PATRICIA KEMP A. COTTON WRIGHT A.B. CHANCE COMPANY 1355 HOLLOWAY DR GRIER FURR CRISP C/O CT CORPORATION SYSTEM PETERBOROUGH ON K9J 6G1 101 N. TRYON ST, STE 1240, 1635 MARKET STREET CANADA CHARLOTTE, NC 28246 PHILADELPHIA, PA 19103 A.F. HOLMAN BOILER WORKS, INC. A.J. BAXTER CO. A.J. ECKERT CO., INC. DALLAS CORPORATE OFFICE ATTN: OFFICER AND/OR MANAGING AGENT C/O COUCH DALE P.C 1956 SINGLETON BOULEVARD 10171 W JEFFERSON AVE. 29 BRITISH AMERICAN BOULEVARD DALLAS, TX 75212 RIVER ROUGE, MI 48218-1301 LATHAM, NEW YORK, 12110. A.L. EASTMOND & SONS, INC. A.M. CASTLE & CO A.O. SMITH CORP. IND. AND AS A PARENT TO EASCO BOULER CORP. ILLINOIS CORPORATION SERVICE COMPANY FKA AOSCO, INC. AS SUCCESSOR TO FEDERAL BOILER 801 ADLAI STEVENSON DR. -

Name City State Country

'271XPEHUVFRXUWHV\RI*ODVVOLQNVFRP 1$0( &,7< 67$7( &28175< LIBBEY-OWENS-FORD CO TOLEDO OHIO USA HAYES-ALBION CORPORATION JACKSON MISSISSIPPI USA TRIPLEX SAFETY GLASS COMPANY LIMITED BIRMINGHAM ENGLAND PPG INDUSTRIES PITTSBURGH PENNSYLVANIA USA PPG CANADA INC., DUPLATE DIVISION OSHAWA ONTARIO CANADA ASAHI GLASS CO LTD TOKYO JAPAN CHRYSLER CORP DETROIT MICHIGAN USA GUARDIAN INDUSTRIES CORP AUBURN HILLS MICHIGAN USA NIPPON SHEET GLASS CO. LTD OSAKA JAPAN SPLINTEX BELGE S.A. GILLY BELGIUM FLACHGLAS AUTOMOTIVE GmbH WITTEN GERMANY CORNING GLASS WORKS CORNING NEW YORK USA SEKURIT SAINT-GOBAIN DEUTSCHLAND GMBH GERMANY GERMANY GLACERIES REUNIES S.A. BELGIUM LAMINATED GLASS CORPORATION DETROIT MICHIGAN USA WITHDRAWN PREMIER AUTOGLASS CORPORATION LANCASTER OHIO USA SOCIETA ITALIANA VETRO S.P.A. SAN SALVO (CHIETI) ITALY SEKURIT SAINT-GOBAIN ITALIA s.r.l. MILANO ITALY N V GLASFABRIEK "SAS VAN GENT" SAS VAN GENT NETHERLANDS SEKURIT SAINT-GOBAIN FRANCE 60150 THOUROTTE FRANCE DEARBORN GLASS COMPANY BEDFORD PARK ILLINOIS USA PILKINGTON FLOATGLAS AB LANDSKRONA SWEDEN WITHDRAWN PPG INDUSTRIES GLASS S.A. LEVALLOIS-PERRET CADES FRANCE CENTRAL GLASS CO LTD TOKYO JAPAN SPLINTEX LTD LONDON ENGLAND CRISTALES INASTILLABLES DE MEXICO S.A. XALOSTOC EDO MEXICO Pilkington Lamino Oy Nordlamex Factory Tampere Finland Seandavian ROHM AND HAAS CO PHILADELPHIA PENNSYLVANIA USA Pilkington Lamino Oy Laitila Factory Laitila Finland Seandavian PILKINGTON SHATTERPROFE SAFETY GLASS PORT ELIZABETH 6000 SOUTH AFRICA VETRERIA DI VERNANTE S.P.A. CUNEO ITALY SHATTERPROOF GLASS CORPORATION DETROIT MICHIGAN USA HSINCHU GLASS WORKS TAIPAI TAIWAN '271XPEHUVFRXUWHV\RI*ODVVOLQNVFRP 1$0( &,7< 67$7( &28175< PILKINGTON SAKERHETSGLAS AB LYSEKIL SWEDEN GLOBE-AMERADA GLASS COMPANY ELK GROVE VILLAGE ILLINOIS USA ARMOUR GLASS COMPANY SANTA FE SPRINGS CALIFORNIA USA AKTIEBOLAGET TREMPLEX ESLOV SWEDEN SHATTERPROOF DE MEXICO S.A. -

Triplex Glass - Originality for MG-T Cars

Triplex Glass - Originality for MG-T Cars Brief History of Glass The origins of Triplex Glass dates back to 1826 when the St Helens Crown Glass Company in England was founded by John William Bell. His technical ability was combined with the capital from three prominent families: Bromilows, Greenalls, and the Pilkingtons. The company was renamed Greenalls and Pilkington in 1829 and after the withdrawal of Greenalls the firm was retitled Pilkington Brothers in 1848. In the late 1830’s and early 40’s the manufacturing of sheets glass had transformed from a process referred to as crown glass to the blown cylinder process. The cylinder process provided a more competitive advantage which allowed Pilkington Glass and a few other companies to dominate the market. By 1876 technology had advanced the plate glass process. This led to a boom in the plate glass industry throughout England. Other countries such as France and Belgium also benefited with increased productivity creating more local competition. With the United States becoming more industrialized and self sufficient the English export market began to wane. This meant that many glass companies failed by the turn of the century leaving Pilkington as one of the survivors. Between 1883 and 1920 the plate glass process had essentially remained the same. Then in a cooperative effort with Ford Motor Company, Pilkington developed a continuous flow process and a method of continuous grinding and polishing. With the rise of mass production in the motor industry, the demand for plate glass was greatly increased. Therefore, the need for the specialized production of safety glass led to the formation in 1923 of the Triplex Safety Glass Company. -

Car Windshields Car Windshields

Car Windshields Car Windshields – DOT Number Database 514 DOT Number Database Database of Department of Transportation Numbers on Windshields All car windshields are required to have a DOT (Department of Transportation) code on them. What does DOT18 mean on glass? How about DOT36? Below you will find a list of DOT numbers that we put together from Various Sources. DOT1 SUPERGLASS S.A. EL TALAR TIGRE BS.AS. ARGENTINA DOT2 J-DAK, INC. SPRINGFIELD TN UNITED STATES DOT3 SACOPLAST S.R.L. OTTIGLIO ALESSANDRIA ITALY DOT4 SOMAVER AIN SEBAA CASABNLANCA MOROCCO DOT5 JIANGUIN JINGEHENG HIGH-QUAL. DECORATING GLASS WORKS JIANGUIN JIANGSU PROVINCE CHINA DOT6 BASKENT GLASS COMPANY SINCAN ANKARA TURKEY DOT7 POLPLASTIC SPA DOLO VENEZIA ITALY DOT8 CEE BAILEYS #1 MONTEBELLO CA DOT9 VIDURGLASS MANBRESA BARCELONA SPAIN DOT10 VITRERIE APRIL, INC. P.A.T. MONREAL QUEBEC CANADA DOT11 SPECTRA INC. MILWAUKEE WI DOT12 DONG SHIN SAFETY GLASS CO., LTD. BOOKILMEON, JEONNAM KOREA DOT13 YAU BONG CAR GLASS CO., LTD. ON LOK CHUEN, NEW TERRITORIES HONG KONG DOT15 LIBBEY-OWENS-FORD CO TOLEDO, OH, USA DOT16 HAYES-ALBION CORPORATION JACKSON, MS, USA DOT17 TRIPLEX SAFETY GLASS COMPANY LIMITED BIRMINGHAM, ENGLAND DOT18 PPG INDUSTRIES PITTSBURGH, PA, USA DOT19 PPG CANADA INC.,DUPLATE DIVISION OSHAWA,ONTARIO, CANADA DOT20 ASAHI GLASS CO LTD TOKYO, JAPAN DOT21 CHRYSLER CORP DETROIT, MI, USA DOT22 GUARDIAN INDUSTRIES CORP AUBURN HILLS, MI, USA DOT23 NIPPON SHEET GLASS CO. LTD OSAKA, JAPAN DOT24 SPLINTEX BELGE S.A. GILLY, BELGIUM DOT25 FLACHGLAS AUTOMOTIVE GmbH WITTEN, GERMANY DOT26 CORNING GLASS WORKS CORNING, NY, USA DOT27 SEKURIT SAINT-GOBAIN DEUTSCHLAND GMBH GERMANY DOT32 GLACERIES REUNIES S.A.