Component-I (A) – Personal Details

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Projected Population of Karnataka 2012-2021

DES No. 22 of 2013 PROJECTED POPULATION OF KARNATAKA 2012-2021 (PROVISIONAL) Issued by: Directorate of Economics and Statistics Bangalore 2013 PREFACE The population census provides information on population and its other characteristics. The census being a decennial exercise does not provide the measure of population change from year to year. The measures of fertility and mortality derived from the census are centered on the mid-point of the decade and as such do not provide any change. Population is one of the most important items for which projections are often made. Though projections may not turn to be precise, they are indicative of the future trends and are useful to the demographers, administrators, planners and to the public at large in different ways. Projections of future populations are also required for preparation of five year plans. Academically also these forecasts are of invaluable utility. With this backdrop an attempt has been made to project the Provisional Population in Karnataka by districts and taluks for rural and urban units separately upto the year 2021. In this attempt only towns with a population of one lakh and above have been covered. These projections are based on the Geometric growth rates between 2001 and 2011 censuses. This exercise was carried out by Civil Registration & National Sample Survey Division of this Directorate. The efforts of Staff/Officers in bringing out this report is very much appreciated. Suggestions, if any for the improvement are most welcome. Date: 18.02.2013 H.E.Rajashekarappa Bangalore Director CONTENTS 1. Population projections for Karnataka 2012-2021- an introductory note. -

Scientific and Technical Study of Bidriware

International Journal of Management, Technology And Engineering ISSN NO : 2249-7455 Scientific and Technical Study of Bidriware Dr. Nalini Avinash Waghmare NISS (Assistant Professor in History) Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth, Pune-37 Mobile No—9975833748 Email: [email protected]. Abstract: Bidar district is the home of the Bidriware industry and the very name Bidri is derived from Bidar. This craft was introduced in Bidar during the rule of Bahmanis. Towards the end of the Baridi dynasty in Bidar this craft reached its zenith and a number of outstanding specimens were produced which today enrich some museums in India and abroad. The basic materials required in Bidri industry are zinc, copper, silver and a particle type of earth. The process of production may be divided into four main stages viz. casting, engraving, inlaying and oxidizing.There are five main types of inlay for ornamenting Bidriware objects. The Bidricraft will be marketed through global media. For improving the life of Bidri artisans and for conservation as well as preservation of Bidriware scientific and technical study of Bidriware is a need of modern time. This paper will be beneficial to artists, historians, researchers, marketing agencies, government and policy makers along with scientist.Through technological help preservation and propaganda about art is also possible . Lastly, it is the work of the researcher to focus on scientific and technical thinking of art for it conservation and preservation of art. Key Words --Bidriware, Bahamani period, metal craft, Bidar, Bidri Artisans 1.Introduction : Bidar is known for its Bidriware. Bidriware brought name and fame to Karnataka. This Bidriware is an art form since Bahamani period to till today. -

Scientific and Technical Study of Bidriware

Scientific and Technical Study of Bidriware Dr. Nalini Avinash Waghmare NISS (Assistant Professor in History) Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth, Pune-37 ABSTRACT: Scientific and Technical Study of Bidriware Bidar district is the home of the Bidriware industry and the very name Bidri is derived from Bidar. This craft was introduced in Bidar during the rule of Bahmanis. Towards the end of the Baridi dynasty in Bidar this craft reached its zenith and a number of outstanding specimens were produced which today enrich some museums in India and abroad. The basic materials required in Bidri industry are zinc, copper, silver and a particle type of earth. The process of production may be divided into four main stages viz. casting, engraving, inlaying and oxidizing.There are five main types of inlay for ornamenting Bidriware objects. The Bidricraft will be marketed through global media. For improving the life of Bidri artisans and for conservation as well as preservation of Bidriware scientific and technical study of Bidriware is a need of modern time. This paper will be beneficial to artists, historians, researchers, marketing agencies, government and policy makers along with scientist.Through technological help preservation and propaganda about art is also possible . Lastly, it is the work of the researcher to focus on scientific and technical thinking of art for it conservation and preservation of art. Key Words --Bidriware, Bahamani period, metal craft, Bidar, Bidri Artisans 1.INTRODUCTION Bidar is known for its Bidriware. Bidriware brought name and fame to Karnataka. This Bidriware is an art form since Bahamani period to till today. Many Bidri artisans brought name to Bidar for demonstrating Bidri articles in India and Abroad. -

Referred'& Reviewed "' , ~. Research Journal '

" ,. ' . ~ ... : .. ~ ~ .. : • • :. ~ 0 .. .. .. ~ .. ~ ••~ ............ III • • • .• ~ ..:..... ...j '......'.. ! '." ~ .~ ... ~.-~ • • • ••.-~ ~ . ... .. .. .. .,' Referred '& Reviewed 1 ' " ' :~:1: ~ .11 ", , • • t ~ ..... ,,, . J _ . '." ,.& •.••• •• •, .• ••. ~ . ......., •• ."••. •• ~ . .. .. ~ •• ' ~' ••• :. " .: ',' . "' , ,~. Research Journal ' ,~" ,,,, ' , ' , " ", , , " , " , ' .. , .... " . .. ,. ' ~.. ' ," . .\.~ :;.":' . ~ :I,..!(b ,. ; 1 . , ," .. ,,;-:.: '.. ~'- -, ," : ':. ~ .... " :" ... L I ...~ '.r· , . ~ " , -~-.. ,- . ._---.._..-_ .... """'I1......--..--............_ ......~· ~....N . ___....I... ...;....; .:__._ •._ . __ :.. _, .. _ _ __... ,; /' f HISTORY , . ISSN - 2250-0383 j RNI-02988/13/01/2011-TC I BIDRIWARE: HAND1CRAFT OF BIDAR DISTRICT j .I. Dr. NaUni Avinasb Wagbmare i Departmentof History S.P.College, Pune-30 Mobile No: 9370063748 Abstract Among the wide range of Indian Islamic metalware, Bidiiware is an 'importantclasl\ of workproduced from the early 171h century until the present day. Bidriware objects have been fashioned in different shapes and adorned with a V!!!iety of tech,ri19':1~. They used' ~y the Deccani and Mughal nobility, as well as by - : --- ::!:!';:;;:;;~- the princ~s an4.affluent people 0 Rajas~an . tlle Punjab Hill States, Bihar, Madhya- . 'J - Pradesh and Western India. -. ~- -- ~ =-- -:::. -. - t Bidar distriCt is the home of the Bidriware industry and the very name Bidri I is derived from Bidar. This craft was introduced in Bidar during the rule of I " Bahmanis. The Bidri articles are well known from their artistic elegance and beauty I in India and abroad. Towards the end ·of the Bmdi dynasty in Bidar this craft j. reached its zenith .and a number of 'outstanding specimens were produced which today enrich some museums in India and abroad. ', The basic materials requi.{ed in Bidri industry are zinc, copper; silver and a Ii particle type of earth. Theprricess of production may be divided into four mmri i · stages viz. casting, engraving, inlaying and oxidizing. -

Cholera Peste

— 125 — Notilications reçues du 6 au 12 mars 1964 — Notifications received from 6 to 12 March 1964 PESTE — PLAGUE CHOLÉRA — CHOLERA C D C D INDE (suite) 2-8.II 9-15.II 16-22.11 Afrique — Africa Asie — Asia INDIA (continued) Mysore, State C D C D Districts TANGANYIKA > 2-29.II BIRMANIE -- BURMA 1-7.IH Belgaum............................. ............ 2p Ip Tanga, Region Moulmein (P) . 1 0 Tumkur B 22-H ............ ............ Ip 2p Rangoon (PA) (excl. Dharwar H 5.III Pare, District .... 455r 9r airport).................. 6 0 ‘ Voir Irtf. épidém.jSea Epidem. Notes: p. 131. Orissa, State Irrawaddy, Division Balasore, District 6 3 Districts Amérique — America West Bengal, State 5 2 Bassein...................... Districts Myaungmya.............. 13 6 C D C D Pyapôn ...................... 1 0 H o w rah ............................. ............ 7p 4p Midnapur . 21p 6p 23p 18p 20p 3p PÉROU — PERU 29.XII-8.1I 9-15.U HONG KONG □ 9.UI Piura, Dep. 26.1-1.11 C D C D Madras, State Huancabamba, Province INDE — INDIA 23-29.11 1-7.III Districts Huancabamba, District 6 ^ 1 2 0 Calcutta (PA) ^ . 14 4 17 4 Coimbatore.............. 69 ‘ Chiffres supplémentaires/SuppIementary figures. 30 Tiruchirapalli (A)............................ 4 1 North Arcot.............. 11 3 2 ^ A l’exclusion de la circonscription de l’aéroport de Tirunelveli.............. 3 Dum-Dum. — Excluding local area of Dum Dum airport. Maharashtra, State Asie — Asia CDC D C D Ratnagiri, District . 6 4 C D 2-8.II 9-15.II 16-22.11 INDE — INDIA I6-22.II Mysore, State Andhra Pradesh, State Bidar, District . 4 1 Andhra Pradesh, State Districts Karimnagar . -

Approved Proposals Under Idmi for the Year 2011-12

APPROVED PROPOSALS UNDER IDMI FOR THE YEAR 2011-12 KARNATAKA (Rs.in lakh) 75% of the proposed Amount proposed Amount amount Sl. to be released as Name of the School / Institute Proposed by (restricted to No. first installment State a maximum (50%) of Rs. 50.00 lakh) St. Joachims Higher Primary School, Kadaba, Puttur, 1 44.5 33.38 16.69 Dakshina, Kannada 594221 Sofiya English High School, 1 st Division, Upparahalli 2 50.75 38.07 19.03 Extension, Tumkur St. Antoney Higher Primary School, Cuttinho Padav, , 3 9.97 7.47 3.73 Ullaibettu, Mallur, Mangalore, Dakshina Kannada 4 SKAH Composite PU College, Basha Nagar, Dvangere 58.62 43.96 21.98 Nau Jawan Talimi Committee, H.No.4-2-16A/1, Noor Khan 5 40.98 30.74 15.37 Rahamath Line, Bidar Hilal-E-Deccan Urdu Higher Primary School, Madina 6 51.13 38.34 19.17 Colony, Roza(K), Gulbarga Alameen Urdu High School, Mannekhehalli, Humnabad, 7 37.34 28 14 Bidar Al.Ameen Urdu Department of Higher Education, Primary 8 41.27 30.96 15.48 School, Hallikhed(B), TQ.Humunabad, Dist. Bidar. 9 Ismail Ideal Public School Kamthana Taluk, Bidar-585226 18.62 13.96 6.98 Christ King English Medium Primary School G.M.Road, 10 66.18 49.64 24.82 Karkala, Udupi-574104. 11 Muslim Welfare Association, Addoor , Mangalore 574145 27.83 20.87 10.44 Catholic Board of Education, Shanthi Kiran, Bajjodi, 12 17.65 13.24 6.62 Mangalore,Dakshina Kannada Allard Education Society,Villa Borromeo, St. Thomas Town, 13 29.46 22.1 11.05 Bangalore 560084 Zikra Education Society ® H.O. -

District Profile Bidar, Karnataka

District Profile Bidar, Karnataka Bidar is one of the oldest districts in Karnataka, dating back to the bifurcation of the state from the erstwhile province of Hyderabad. Located about 700 km from Bangalore, Bidar lies in the farthest north-eastern corner of Karnataka. It has five Taluks (Aurad, Basavakalyan, Bhalki, Bidar and Humnabad). There are 30 hoblies, 175 gram panchayats, six municipal corporation, 599 inhabitations/thandas and 22 uninhabited villages. DEMOGRAPHY As per Census 2011, the total population of Bidar is 17,03,300 which accounts for 2.78 percent of the total population of State. Out of which 8,70,665 were males and 8,32,635 were females. This gives a sex ratio of 956 females per 1000 males. The percentage of urban population in Bidar is 25.01 percent, which is lower than the state average of 38.6 percent. The decadal growth rate of population in Karnataka is 15.60 percent, while Bidar reports a 13.37 percent decadal increase in the population. The decadal growth rate of urban population in Karnataka is 4.58 percent, while Bidar reports a 1.94 percent. The district popula- tion density is 313 in 2011, which has increased from 276 since 2001. The Scheduled Caste population in the district is 24 percent while Scheduled Tribe comprises 14 percent of the population. LITERACY The overall literacy rate of Bidar district is 70.51 percent while the male & fe- male literacy rate is 79.09 and 61.55 percent respectively. At the block level, a considerable variation is noticeable in male-female literacy rate. -

![The Delimitation of Council Constituencies 2[(Karnataka)] Order, 1951](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8093/the-delimitation-of-council-constituencies-2-karnataka-order-1951-1028093.webp)

The Delimitation of Council Constituencies 2[(Karnataka)] Order, 1951

217 1THE DELIMITATION OF COUNCIL CONSTITUENCIES 2[(KARNATAKA)] ORDER, 1951 In pursuance of section 11 of the Representation of the People Act, 1950 (43 of 1950), the President is pleased to make the following Order, namely:— 1. This Order may be called the Delimitation of Council Constituencies 2[(Karnataka)] Order, 1951. 2. The constituencies into which the State of 3[Karnataka] shall be divided for the purpose of elections to the Legislative Council of the State from (a) the graduates' constituencies, (b) the teachers' constituencies, and (c) the local authorities' constituencies in the said State, the extent of each such constituency and the number of seats allotted to each such constituency shall be as shown in the following Table:— 2[TABLE Name of Constituency Extent of Constituency Number of seats 1 2 3 Graduates' Constituencies 1. Karnataka North-East Graduates Bidar, Gulbarga, Raichur and Koppal districts and Bellary 1 districts including Harapanahalli taluk of Davanagere district 2. Karnataka North-West Graduates B ijapur, Bagalkot and Belgaum districts 1 3. Karnataka West Graduates Dharwad, Haveri, Gadag and Uttara Kannada districts 1 4. Karnataka South-East Graduates Chitrradurga, Davanagere (excluding taluks of Channagiri, 1 Honnall and Harapanahalli), Tumkur and Kolar districts 5. Karnataka South-West Graduates Shimoga district including channagiri and Honnalli taluks of 1 Davanagere district, Dakshina Kannada, Udupi, Chickmagalur and Kodagu districts 6. Karnataka South-Graduates Mysore, Chamarajanagar, Mandya and Hassan districts 1 7. Bangalore Graduates Banagalore and Banagalore rural districts 1 Teachers’ Constituencies 1. Karnataka North-East Teachers Bidar, Gulbarga, Raichur and Koppal districts and Bellary 1 districts including Harapanahalli taluk of Davanagere district 2. -

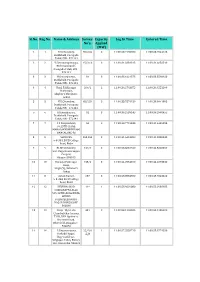

Sl.No. Reg.No. Name & Address Survey No's. Capacity Applied (MW

Sl.No. Reg.No. Name & Address Survey Capacity Log In Time Entered Time No's. Applied (MW) 1 1 H.V.Chowdary, 65/2,84 3 11:00:23.7195700 11:00:23.7544125 Doddahalli, Pavagada Taluk, PIN - 572141 2 2 Y.Satyanarayanappa, 15/2,16 3 11:00:31.3381315 11:00:31.6656510 Bheemunikunte, Pavagada Taluk, PIN - 572141 3 3 H.Ramanjaneya, 81 3 11:00:33.1021575 11:00:33.5590920 Doddahalli, Pavagada Taluk, PIN - 572141 4 4 Hanji Fakkirappa 209/2 2 11:00:36.2763875 11:00:36.4551190 Mariyappa, Shigli(V), Shirahatti, Gadag 5 5 H.V.Chowdary, 65/2,84 3 11:00:38.7876150 11:00:39.0641995 Doddahalli, Pavagada Taluk, PIN - 572141 6 6 H.Ramanjaneya, 81 3 11:00:39.2539145 11:00:39.2998455 Doddahalli, Pavagada Taluk, PIN - 572141 7 7 C S Nanjundaiah, 56 2 11:00:40.7716345 11:00:41.4406295 #6,15TH CROSS, MAHALAKHSMIPURAM, BANGALORE-86 8 8 SRINIVAS, 263,264 3 11:00:41.6413280 11:00:41.8300445 9-8-384, B.V.B College Road, Bidar 9 9 BLDE University, 139/1 3 11:00:23.8031920 11:00:42.5020350 Smt. Bagaramma Sajjan Campus, Bijapur-586103 10 10 Basappa Fakirappa 155/2 3 11:00:44.2554010 11:00:44.2873530 Hanji, Shigli (V), Shirahatti Gadag 11 11 Ashok Kumar, 287 3 11:00:48.8584860 11:00:48.9543420 9-8-384, B.V.B College Road, Bidar 12 12 DEVUBAI W/O 11* 1 11:00:53.9029080 11:00:55.2938185 SHARANAPPA ALLE, 549 12TH CROSS IDEAL HOMES RAJARAJESHWARI NAGAR BANGALORE 560098 13 13 Girija W/o Late 481 2 11:00:58.1295585 11:00:58.1285600 ChandraSekar kamma, T105, DNA Opulence, Borewell Road, Whitefield, Bangalore - 560066 14 14 P.Satyanarayana, 22/*/A 1 11:00:57.2558710 11:00:58.8774350 Seshadri Nagar, ¤ltĔ Bagewadi Post, Siriguppa Taluq, Bellary Dist, Karnataka-583121 Sl.No. -

Friday 5 August 2016

Friday 5thAugust 2016 (For the period 5th to 9thAugust 2016) Weblink For District AAS Bulletin: http://www.imdagrimet.gov.in/node/3545 State Composite AAS Bulletin: http://www.imdagrimet.gov.in/node/3544 1 Standardised Precipitation Index Four Weekly for the Period 7th July to 3rd August 2016 Extremely/severely wet conditions experienced in Baksa district of Assam; Araria district of Bihar; Kheri, Mirzapur, Agra, Bareilly, Etah districts of Uttar Pradesh; Betul, Bhopal, Hoshangabad, Khandwa, Sehore, Satna districts of Madhya Pradesh; Nashik, Buldhana districts of Maharashtra; Anantapur district of Andhra Pradesh; Krishnagiri district of TamilNadu; Bangalore Rural, Bangalore Urban, Kolar, Mandya, Tumkur, Ramanagara, Chickballapur districts of Karnataka. Extremely/Severely dry conditions experienced in Jaintia Hills district of Meghalaya; Kohima district of Nagaland; Howrah district of West Bengal; Chatra, Dhanbad district of Jharkhand; Jamui districts of Bihar; Ambedkar Nagar, Kannauj, Kaushambi, Ghaziabad districts of Uttar Pradesh; Ambala, Kurukshetra, Sirsa, Panchkula districts of Haryana; Hoshiarpur, Barnala districts of Punjab; Bilaspur, Lahaul & Spiti districts of Himachal Pradesh; Jashpur district of Chhattisgarh; Coimbatore district of Tamil Nadu; Uttar Kannada, Udupi, Shimoga districts of Karnataka; Wynad district of Kerala. Moderately dry conditions experienced in few districts of Jharkhand; Punjab; Himachal Pradesh; Shonitpur, Hailakandi districts of Assam; Aizwal district of Mizoram; South Dinajpur district of West Bengal; Bolangir, Malkangiri, Kandhamal, Sambalpur, Sonepur districts of Odisha; Nawada, Sheikhpura districts of Bihar; Farrukhabad, Kanpur Dehat, Kushi Nagar, Mainpuri districts of Uttar Pradesh; Kaithal district of Haryana; Barmer, Hanumangarh districts of Rajasthan; Bilaspur, Surguja district of Chhattisgarh; Tiruvallur, Puducherry districts of TamilNadu & Puducherry; Dakshin Kannada, Chikmagalur, Hassan, Kodagu districts of Karnataka; Cannur, Malappuram, Kasargod districts of Kerala. -

Kolhar Industrial Area Phase-II”, Kolhar Village, Bidar District, Karnataka

Pre-feasibility Report for Setting of Kolhar Industrial Area by M/s Karnataka Industrial Areas Development Board (KIADB) Pre-Feasibility Report On Setting of ”Kolhar Industrial Area Phase-II”, Kolhar village, Bidar District, Karnataka For Karnataka Industrial Areas Development Board 14/3, II Floor, Rastrothana Parishad Building, Nrupatunga Road, Banagalore-560001 Prepared by: M/s Bhagavathi Ana Labs Ltd 8-2-248/42/A/5, Venkateshwara Hills Colony, Road No 3 Banjara Hills, Hyderabad – 500 034 M/s Bhagavathi Ana Labs Ltd., Hyderabad Page 1 of 25 Pre-feasibility Report for Setting of Kolhar Industrial Area by M/s Karnataka Industrial Areas Development Board (KIADB) CONTENTS S. No Description Page No. 1 Introduction of the Project 3 2 Project Description 7 3 Site Analysis 14 4 Project Planning 16 5 Infrastructure Development 17 6 Resettlement and Rehabilitation Plan 19 7 Market Assessment 20 8 Project Cost Estimation 23 9 Legal Frame Work 24 10 Analysis of Proposal and Final Recommendation 25 M/s Bhagavathi Ana Labs Ltd., Hyderabad Page 2 of 25 Pre-feasibility Report for Setting of Kolhar Industrial Area by M/s Karnataka Industrial Areas Development Board (KIADB) 1. INTRODUCTION OF THE PROJECT 1.0 Introduction State Karnataka considered as a pioneer in the field of industrialization in India. The State is in the forefront of industrial growth of our country since independence. In the era of economic liberalization since 1991, the State has been spearheading the growth of Indian industry, particularly in terms of high- technology industries such as Electrical and Electronics Automobile Spare Parts, Information & Communication Technology (ICT) Biotechnology, etc., and also State enters recently in terms of establishment of Nanotechnology industries. -

Unit 10 Emergence of Rashtrakutas*

History of India from C. 300 C.E. to 1206 UNIT 10 EMERGENCE OF RASHTRAKUTAS* Structure 10.0 Objectives 10.1 Introduction 10.2 Historical Backgrounds of the Empire 10.3 The Rashtrakuta Empire 10.4 Disintegration of the Empire 10.5 Administration 10.6 Polity, Society, Religion, Literature 10.7 Summary 10.8 Key Words 10.9 Answers to Check Your Progress Exercises 10.10 Suggested Readings 10.0 OBJECTIVES In this Unit, we will discuss about the origin and emergence of the Rashtrakutas and the formation of Rashtrakuta empire. Later, we will also explore the organization and nature of Rashtrakuta state with social, religious, educational, cultural achievements during the Rashtrakutas. After studying the Unit, you will be able to learn about: major and minor kingdoms that were ruling over different territories of south India between 8th and 11th centuries; emergence of the Rashtrakutas as a dominant power in Deccan; the process of the formation of Rashtrakuta empire and contributions of different kings; the nature of early medieval polity and administration in the Deccan; significant components of the feudal political structure such as ideological bases, bureaucracy, military, control mechanism, villages etc.; and social, religious, educational, architectural and cultural developments within the Rashtrakuta empire. 10.1 INTRODUCTION India witnessed three powerful kingdoms between c. 750 and 1000 CE: Pala empire, Pratihara empire and Rashtrakuta empire in south India. These kingdoms fought each other to establish their respective hegemony which was the trend of early medieval India. Historian Noboru Karashima treats the empire as a new type of state, i.e.