Ltd. Versus Federation of Pakistan & O

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

At the Right Price

Manufacturer of OEM'S PLASTIC PARTS & Lamp Assemblies GET THE RIGHT PARTS AT THE RIGHT PRICE Trustedbyleadingautomotivecompaniessince1988 www.galaxyengg.com.pk Resource Result & Reliability We have specialized in the Injection Molding of Engineering Plastic Materials especially for OEM Automobile Plastic Parts & Lamps Assemblies, Appliances parts, Industrial parts etc. Tractors, Home Appliance and other Industries. Customised Solutions Galaxy Polymer Industries, manufacturers a wide range of injection and Plastic Parts & Lamps Assemblies for some of the leading automotive giants, for passenger as well as commercial vehicles. Glaxy Polymer Industries is an ISO 9001:2015 certified company, engaged in the business of manufacturing Plastic Parts & Lamps Assemblies since 1988. In-house R&D facilities, die room, and highly skilled manpower, GPE has a customized designs, and maintaining consistent quality norms ensuring complete reliability with competitive price. GPE Plant We have 10 injection molding machines ranging from 15 ton to 500 ton. The weight capacity is ranging from 10gram to 1600gram. Assembly Shop:: Quality Policy We have 03 dedicated stations for assembly parts and lamps. We are produc- Glaxy Polymer Industries ing 10 different types of lamps and 04 precision assembly parts for automobile is committed to building sector. long-lasting relationshops with its cutomers by Glaxy Polymer Industries is a trusted supplier of Banking Sector ensuring therir success we are manufacturing banking equipment such as Cash Tray & Seal throgh strict quality control GPE Product Range The images are only representatives of current products. please send the details of your requirements with specifications and we shall be able to provide cost effective solutions with shortest possible turn around times. -

A Solid Relief Rally; 5 May 2020 Breather Can Be Forgiven

Pakistan Equities Monthly Commentary A solid relief rally; 5 May 2020 breather can be forgiven . Interestingly, the local stock market and crude oil (WTI) both happened to Syed Hussain Haider, CFA, CIPM close the month at key resistance levels. Both have already gone through [email protected] a commendable relief rally; WTI has doubled and the KSE-100 has posted +9221 111-574-111 Ext: 3118 25% returns. Hence, any breather during May should not be concerning. Ali H. Zaidi [email protected] . Looking at the decent stock market performance in the ongoing holy +9221 111-574-111 Ext: 3103 month, it might just be the best one in a decade. However, empirical evidence suggests May has historically been relatively tamer. Perhaps this Ahmed Lakhani time, we could be in for something different? [email protected] +9221 111-574-111 Ext: 3035 . Presently, the market is basking in the glory of sympathetic measures (and potential budgetary relief around the corner) in lieu of Covid-19 – both local and foreign. Also, even with the back-to-back policy-rate cuts already announced by the central bank, a further cumulative 200bps cut (at least 100 bps in coming MPC meeting) should not be too surprising. With the market trading at forward P/E of 6.2x and a forward P/B of 1.03x (10-yr average of 8.2x and 1.6x) as per Bloomberg, there is no denying that valuations are more than attractive from a longer term perspective, even though the near-term earnings outlook remains hazy. -

Annual Report 2018-19

NED UNIVERSITY OF ENGINEERING & TECHNOLOGY Annual Report 2018-19 Directorate of Industrial Liaison DIRECTORATE OF INDUSTRIAL LIAISON ANNUAL REPORT ( 1ST JULY-2018 TO 30th JUNE-2019) The DIL was established at NED University of Engineering & Technology in 1997. The prime objectives of DIL are to create and enhance the required University-Industry Linkages in the form of various activities mostly related to the interaction with industries and finding opportunities for students becoming involved in practical training before graduation. Key areas can be categorized as follows: 1. Arranging internships in different industries during vacations. 2. Organizing study tours of industries and visits for students and faculty members. 3. Securing orders for projects and/or suggestions for new Research from industries for final year students and research scholars. 4. Facilitate NED graduates in obtaining suitable employment depending on requirements of the job market; also at the same time facilitating prospective employers to contact graduates by arranging tests and interviews. The Directorate of Industrial Liaison performed following core jobs during the year. (March 2018 to March 2019) a. 1270 Internships opportunities provided during Ramdhan Break. b. 1402 Internship opportunities were provided during Vacations. c. 54 industrial/ study visits were arranged. March to June 2018: 11 and July to March 2019: 43. d. 626 projects for final year students. e. 483 activities for facilitating employment were conducted jointly with various employers, including direct on-campus hiring, sharing of graduate directories, placing job ads on department and web notice boards and conducting informative seminars. March~Jun-2018; Batch 2013-14 (On-Campus Hiring: 08, GD’s & Ads: 131) Jul-18~Mar-19; Batch 2013-14 (On-Campus hiring: 2, GD’s & Ads: 56) Jul-18~Mar-19; Batch 2014-15 (On-Campus hiring: 26, GD’s & Ads: 258) Seminars/ Workshops: 03 f. -

India-Pakistan Trade: Perspectives from the Automobile Sector in Pakistan

Working Paper 293 India-Pakistan Trade: Perspectives from the Automobile Sector in Pakistan Vaqar Ahmed Samavia Batool January 2015 1 INDIAN COUNCIL FOR RESEARCH ON INTERNATIONAL ECONOMIC RELATIONS Table of Contents List of Abbreviations ................................................................................................................... iii Abstract ......................................................................................................................................... iv 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 1 2. Methodology and Data .......................................................................................................... 2 3. Automobile Industry in Pakistan ......................................................................................... 3 3.1 Evolution and Key Players............................................................................................ 4 3.2 Structure of the Industry ............................................................................................... 6 3.3 Production structure ..................................................................................................... 7 3.4 Market Structure ........................................................................................................... 8 4. Automobile Trade of Pakistan............................................................................................ 10 4.1 Import -

Financial Analysis of Toyota Indus Motor Company

Financial Analysis of Toyota Indus Motor Company 2017 Financial Analysis of Toyota Indus Motor Company Financial Year 2011-2016 Ayesha Majid Lahore School of economics 5/1/2017 Financial Analysis of Toyota Indus Motor Company i Table of Contents Preamble .................................................................................................................... 1 Categories of Financial Ratios Analysed ................................................................ 1 Limitations .............................................................................................................. 2 Toyota Indus Motors................................................................................................... 3 Company Profile ..................................................................................................... 3 Financial Profile ...................................................................................................... 3 Introduction ............................................................................................................. 4 Mission Statement ............................................................................................... 5 Vision Statement ................................................................................................. 5 Slogan ................................................................................................................. 5 Quote Summary as on 1st May 2017 .......................................................................... 6 -

Role of Automobile Industry in Economic Development of Pakistan by Aqil, 2009, HIESS and PAMA

DETERMINANTS OF THE PERFORMANCE OF AUTOMOBILE INDUSTRY FROM 1995 TO 2010-A CASE STUDY OF PAKISTAN Thesis By MUHAMMAD AQIL In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph. D.) in Social Sciences Under the Supervision of DR. FAROOQ AZIZ Presented to Hamdard Institute of Education and Social Sciences HAMDARD UNIVERSITY July 2014 Dedicated to My Parents, Wife and Children Who always support me! i Abstract The study was primarily a quantitative and causal research. Its basic objective was to find out the nature and degree of macroeconomic factors that influence the performance of automobile industry in Pakistan from 1995 to 2010. The independent variables included per capita Gross National Income, Inflation Rate, Exchange Rate, Discount Rate, Unemployment Rate, Consumption Rate and Foreign Direct Investment. A sample of 10 firms was selected to explore the influence of macroeconomic variables on the performance of the firms and industry. The performance of the automobile industry was represented by Annual Sales, Annual Profit, Return on Assets, Return on Equity and Net Profit Margin. The impact of selected predictors was explored on five dependent variables of the industry. For this purpose, regression and correlation analysis was conducted to see the impact of macroeconomic variables on the performance of entire automobile industry. The panel data analysis revealed that Foreign Direct Investment was the most influential factor. In addition to this, Consumption rate, Discount rate and Unemployment rate also influenced the performance of automobile industry. Besides the analysis of entire industry, the impact of macroeconomic variables on the performance of individual firms was also studied. -

In the High Court of Sindh at Karachi

IN THE HIGH COURT OF SINDH AT KARACHI High Court Appeal No.60 of 2012 Before: Mr. Justice Irfan Saadat Khan & Mr. Justice Zafar Ahmed Rajput Dates of Hearing: 27.01.2014, 03.02.2014, 13.03.2014 & 19.03.2014. Date of decision: .04.2014. Mr. Abid S. Zuberi, Advocate for the appellant Karachi Electric Supply Company. Mr. Abrar Hasan, Advocate for the respondent No.1 Karachi Water & Sewerage Board Mr. Dilawar Hussain, Standing Counsel for the respondent No.2 Federation of Pakistan. Mr. Meeran Muhammad Shah, Additional Advocate General Sindh for the respondent No.3 Province of Sindh. None for the respondent No.4 City District Government Karachi. O R D E R IRFAN SAADAT KHAN, J:- This High Court Appeal (HCA) has been filed against the order dated 25.04.2012 passed by the learned Single Judge of this Court in Suit No.1263 of 2011 whereby three Civil Miscellaneous Applications i.e. (1) CMA Nos.10555/2011, under Order XXXIX Rules 1 & 2 CPC, (2) 10556/2011, under Order XXXIX Rules 1 & 2 C and (3) 2737/2012, under Order XXXIX Rule 4 CPC read with Section 151 CPC, filed by the respondent No.1/plaintiff, were allowed. 2. Briefly stated the facts of the case are that the Karachi Electric Supply Corporation (KESC) is a privately owned utility company and 2 is engaged in the business of generation, transmission and distribution of electricity within its licensed area spread over to Karachi and its suburbs upto Dhabeji, Gharo in Sindh and Hub, Uthal, Vindhar and Bela in Baluchistan and the respondent No.1 i.e. -

Identification and Estimation of the Role of Internal Micro Level Factors Towards Efficient Working Capital Management

Identification and Estimation of the Role of Internal Micro Level Factors Towards Efficient Working Capital Management A case study based on the experience of manufacturing firms in Pakistan. By Shahid Ali A research thesis submitted to the Department of Management & Social Sciences, Mohammad Ali Jinnah University, Islamabad In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN MANAGEMENT SCIENCES (FINANCE) DEPARTMENT OF MANAGEMENT & SOCIAL SCIENCES MOHAMMAD ALI JINNAH UNIVERSITY ISLAMABAD JANUARY 2012 Identification and Estimation of the Role of Internal Micro Level Factors Towards Efficient Working Capital Management A case study based on the experience of manufacturing firms in Pakistan. By Shahid Ali A research thesis submitted to the Department of Management & Social Sciences, Mohammad Ali Jinnah University, Islamabad In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN MANAGEMENT SCIENCES (FINANCE) DEPARTMENT OF MANAGEMENT & SOCIAL SCIENCES MOHAMMAD ALI JINNAH UNIVERSITY ISLAMABAD JANUARY 2012 Identification and Estimation of the Role of Internal Micro Level Factors Towards Efficient Working Capital Management A case study based on the experience of manufacturing firms in Pakistan. By Shahid Ali (PM073008) Professor Dr. Tudorel Andrei The Bucharest Academy of Economic Studies, Romania Dr. Claudiu Herteliu University of Economic Studies, Romania ______________________________________ Professor Dr. Muhammad Ramzan Akhtar ______________________________________ Dr. Sajid -

BULLETIN March - April 2003

ECONOMIC BULLETIN March - April 2003 Contents § Editor’s Corner ii § Abstract of the Bulletin 04 § WTO, The Agreements and their Implications for Developing Countries, with Special Reference to Pakistan 05 § Pre-Budget 2003-04 10 § Pakistan’s Automobile Industry 13 § Agriculture 18 § Banking & Finance 20 § Market Analysis 21 § Investment Potential of Pakistan 22 § Economic Performance at a Glance 23 § Key Economic Indicators 24 NBP Performance at a Glance ECONOMIC BULLETIN March - April 2003 Editor’s Corner Dear readers Since July 2001, the State Bank of Pakistan is pursuing an easy monetary policy. Interest rate structure has been rationalised; Discount rate reduction has been accompanied with commercial banks reducing their lending rate. Export refinance rate, which is linked with the yield on 6-month treasury bills has fallen. Simultaneously, the Government has reduced the returns on the National Saving Schemes, and the profit rates on Defence Saving Certificates have been linked to the respective maturity yields on Pakistan Investment Bonds. The higher profit rates offered on National Saving Schemes (NSS), had attracted in its fold, a number of investors both from the government and the private sector. While they had secured a relatively safe future for themselves and their families, these high profit rates had raised the debt servicing burden of domestic debt to unsustainable levels and had begun to have distortionary implications for monetary policy in the last 2-3 years as inflationary pressures eased. In the early 1980s, the government had started paying high nominal interest rates on NSS, while inflation was still relatively low. During this period, its impact on government interest payments was, however, dampened because borrowing through NSS was small and the bulk of this borrowing was in the form of zero coupon five or ten year certificates, the interest on which was recorded when the certificates were encashed. -

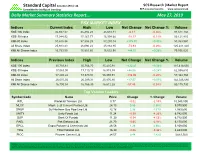

Daily Market Summary Statistics Report…. July 23, 2019

Standard Capital Securities (Pvt.) Ltd. SCS Research | Market Report Committed to intelligent investing REP-033 also log onto www.jamapunji.pk Daily Market Summary Statistics Report…. July 23, 2019 REP-033 also log onto www.jamapunji.pk PSX MARKET INDEX Indices Current Index High Low Net Change Net Change % Volume KSE 100 Index 32,715.88 32,758.44 32,455.10 +131.33 +0.40% 79,621,900 KSE-30 Index 15,564.28 15,576.64 15,423.49 +86.85 +0.56% 50,821,490 KMI-30 Index 51,603.74 51,727.91 51,121.56 +298.71 +0.58% 44,838,490 All Share Index 23,896.48 23,970.68 23,755.18 +17.80 +0.07% 97,118,100 KMI All Shares Index 15,185.49 15,223.49 15,062.37 +66.89 +0.44% 61,968,640 Indices Previous Index High Low Net Change Net Change % Volume KSE 100 Index 32,584.55 32,735.83 32,391.55 +125.78 +0.39% 38,193,800 KSE-30 Index 15,477.43 15,560.80 15,356.98 +81.84 +0.53% 27,774,410 KMI-30 Index 51,305.03 51,525.56 50,778.58 +300.51 +0.59% 23,103,310 All Share Index 23,878.68 23,948.45 23,776.34 +62.92 +0.26% 44,702,350 KMI All Shares Index 15,118.60 15,155.67 15,005.86 +67.00 +0.44% 28,249,630 Top Volume Leaders Symbol Code Name Price Change % Change Volume MLCF Maple Leaf Cement Factory Ltd. -

Daily Market Summary Statistics Report…. May 27, 2019

Standard Capital Securities (Pvt.) Ltd. SCS Research | Market Report Committed to intelligent investing REP-033 also log onto www.jamapunji.pk Daily Market Summary Statistics Report…. May 27, 2019 REP-033 also log onto www.jamapunji.pk PSX MARKET INDEX Indices Current Index High Low Net Change Net Change % Volume KSE 100 Index 35,697.37 35,892.29 35,610.41 -6.44 -0.02% 94,511,150 KSE-30 Index 17,044.92 17,167.77 16,994.66 -18.17 -0.11% 59,121,810 KMI-30 Index 57,615.94 57,956.29 57,230.14 +175.70 +0.30% 57,363,960 All Share Index 25,933.43 26,096.22 25,864.85 -73.93 -0.29% 125,221,420 KMI All Shares Index 16,753.55 16,801.60 16,652.98 +44.01 +0.26% 79,936,020 Indices Previous Index High Low Net Change Net Change % Volume KSE 100 Index 35,703.81 35,766.70 35,435.91 +122.47 +0.34% 110,418,650 KSE-30 Index 17,063.09 17,110.13 16,919.74 +48.58 +0.28% 62,055,610 KMI-30 Index 57,440.24 57,670.01 56,898.91 -116.06 -0.20% 57,364,760 All Share Index 26,007.36 26,039.31 25,876.80 +17.57 +0.07% 142,026,680 KMI All Shares Index 16,709.54 16,766.99 16,612.28 -57.45 -0.34% 89,175,730 Top Volume Leaders Symbol Code Name Price Change % Change Volume WTL Worldcall Telecom Ltd. -

Fig 3.3.2 Supply Chain Model Optimized for Assembling Vehicles………………………

P OLITECNICO DI TORINO THE AUTOMOTIVE INDUSTRY IN PAKISTAN SUPERVISOR : L UIGI BENFRATELLO CANDIDATE : S OHAIL IQBAL 1 Table of Contents -List of Figures………………………………………………………….....4 -List of Tables …………………………………………………....……......5 -Abstract…………………………………………………………...…........6 1. Introduction 1.1 Historical Overview ……………………………………………...…...7 2. The Economy of Pakistan 2.1 Overview …………………………………………………………......11 2.2 Economic Geography of Pakistan …………………………………....13 3. The Automotive Sector 3.1 Historic Development in Pakistan's Automotive Sector……………....16 3.2 Major Players……………………………………………………….....17 3.2.1 Pak-Suzuki Motors………………………………………….. 17 3.2.2 Indus Motors Company ……………………………………...18 3.2.3 Honda Atlas ………………………………………………….18 3.3 Production Structure ………………………………………………….19 3.4 Automotive Trade in Pakistan………………………………………...22 3.5 Informal / Illegal Trade in Automotive Industry ……………………..25 3.6 Trade Prospective with India …………………………………………26 4. Strategic Analysis Review 4.1 Porter's Five Forces 4.1.1 Bargaining Power of Buyers………………………………...29 4.1.2 Bargaining Power of Suppliers……………………………...29 4.1.3 Threat of Substitute Products………………………………..30 4.1.4 Industry Rivalry …………………………………………….30 4.1.5 Threat of New Entrants ……………………………………..31 4.2 SWOT Analysis 4.2.1 Strengths………………………………………………..........32 2 4.2.2 Weaknesses ………………………………………………....32 4.2.3 Opportunities…………………………………….….............33 4.2.4 Threats ……………………………………………………...33 4.3 Porter's Diamond Model 4.3.1 Demand Conditions ………………………………………...34 4.3.2 Context for Firm