Editorial Reviews of “Bound for Canaan” by Fergus M. Bordewich

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monuments and Memories in Ontario, 1850-2001

FORGING ICONOGRAPHIES AND CASTING COLONIALISM: MONUMENTS AND MEMORIES IN ONTARIO, 1850-2001 By Brittney Anne Bos A thesis submitted to the Department of History In conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada (September 2016) Copyright ©Brittney Anne Bos, 2016 ii Abstract Commemorations are a critical window for exploring the social, political, and cultural trends of a specific time period. Over the past two centuries, the commemorative landscape of Ontario reaffirmed the inclusion/exclusion of particular racial groups. Intended as static markers to the past, monuments in particular visually demonstrated the boundaries of a community and acted as ongoing memorials to existing social structures. Using a specific type of iconography and visual language, the creators of monuments imbued the physical markers of stone and bronze with racialized meanings. As builders were connected with their own time periods and social contexts, the ideas behind these commemorations shifted. Nonetheless, creators were intent on producing a memorial that educated present and future generations on the boundaries of their “imagined communities.” This dissertation considers the carefully chosen iconographies of Ontario’s monuments and how visual symbolism was attached to historical memory. Through the examination of five case studies, this dissertation examines the shifting commemorative landscape of Ontario and how memorials were used to mark the boundaries of communities. By integrating the visual analysis of monuments and related images, it bridges a methodological and theoretical gap between history and art history. This dissertation opens an important dialogue between these fields of study and demonstrates how monuments themselves are critical “documents” of the past. -

Freedom Seekers: the Underground Railroad, Great Lakes, and Science Literacy Activities Middle School and High School Curriculum

Freedom Seekers: The Underground Railroad, Great Lakes, and Science Literacy Activities Middle School and High School Curriculum “Joe, come look at de Falls! ... it's your last chance. Joe, you’ve shook de lion’s paw!, You’re free!” --Harriet Tubman 1 Freedom Seekers Curriculum Committee Monica Miles, Ph.D. | New York Sea Grant Fatama Attie | University at Buffalo Bhawna Chowdary, Ph.D. | Niagara Falls City Schools/University at Buffalo James Ponzo, Ph.D. | University at Buffalo & Niagara Falls Underground Railroad Heritage Center Claudia Rosen | Buffalo Niagara Waterkeeper Kate Haq, Ph.D. | The Park School of Buffalo Betsy Ukeritis | NYS Department of Environmental Conservation Ginny Carlton, Ph.D. | Wisconsin Sea Grant Meaghan Gass, editor | Michigan Sea Grant, MI State University Extension Megan L. Gunn, editor | Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant The curriculum committee would like to extend our thanks and appreciation to everyone who contributed to this curriculum including article authors and reviewers. Thank you for helping us share the story of Freedom Seekers! 2 Contents of Lesson Series Freedom Seekers Curriculum Committee 2 Contents of Lesson Series 3 Letter to Educators 4 Educator Resources 5 Underground Railroad Lessons 7 Lesson 1 - Harriet Tubman--the unsung naturalist 9 Lesson 2 - The Underground Railroad and Maritime Connections 19 Lesson 3 - How to Conduct Historical Research 25 Lesson 4 - Connecting Environmental Resources to Historically Rich Spaces 29 Lesson 5 - Examining the Remains of the Cataract House 33 Lesson 6 - Using US Census Data to Investigate the Underground Railroad 42 Lesson 7 - Race and the US Census 53 Lesson 8 - Native Americans and the Underground Railroad 59 Extension Activities Educator Resources 66 African American History and Science Extension Activities 67 Activity 1 - U.S. -

The Search for George Debaptiste's House: the Crooked Creek Flood

The Search for George DeBaptiste’s House: The Crooked Creek Flood of 1846 Christopher Baas and Darrin L. Rubino Summary We used archival sources and Geographic Information Systems data to demonstrate the feasibility of the 1846 Crooked Creek Flood (Madison, Indiana, USA) having destroyed the home connected to abolitionist and Underground Railroad leader George DeBaptiste. George DeBaptiste (1814–1875) was an African American abolitionist and a prominent figure in the Underground Railroad (UGRR), the network used by African American slaves in the Southern US to escape to free Northern states. He resided in Madison, Indiana, between 1838 and 1846, when he moved his family to Detroit, Michigan, following local race riots against UGRR leaders. In an effort to preserve the heritage of this icon’s legacy, preservationists used historical documentation to determine the likely location of DeBaptiste’s house. We performed tree-ring analysis to confirm if the existing house on the property was, in fact, DeBaptiste’s house. Determining the construction date of a structure using tree rings is performed by obtaining samples from a structure’s timbers and matching their tree-ring growth patterns to regional historic growth patterns. Analysis showed that the structure’s timbers were harvested sometime after the spring of 1846. These results were puzzling since DeBaptiste left Madison in 1846. It is unlikely that DeBaptiste would have constructed a new structure while racial tensions were reaching a fever pitch. Investigating Madison’s history provided a potential clue. Baas, Christopher, and Darrin L. Rubino. “The Search for George DeBaptiste’s House: The Crooked Creek Flood of 1846.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (Spring 2020), no. -

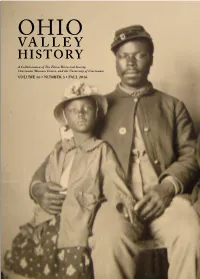

Volume 16 • Number 3 • Fall 2016

OHIO VALLEY HISTORY VALLEY OHIO Periodicals postage paid at Cincinnati, Ohio, and additional mailing offices. A Collaboration of The Filson Historical Society, Cincinnati Museum Center, and the University of Cincinnati. VOLUME 16 • NUMBER 3 • FALL 2016 VOLUME • NUMBER 16 3 • FALL 2016 Ohio Valley History is a Submission Information for Contributors to OHIO VALLEY STAFF David Stradling Phillip C. Long collaboration of The Filson University of Cincinnati Julia Poston Editors Nikki M. Taylor Thomas H. Quinn Historical Society, Cincinnati LeeAnn Whites Texas Southern University Joanna Reeder Museum Center, and the The Filson Historical Society Frank Towers Dr. Anya Sanchez Department of History, University Matthew Norman University of Calgary Judith K. Stein, M.D. Department of History Steve Steinman of Cincinnati. University of Cincinnati CINCINNATI Carolyn M. Tastad Blue Ash College MUSEUM CENTER Anne Drackett Thomas Cincinnati Museum Center and One digital copy of the manuscript, saved in Microsoft Word, *Regarding general form and style, please follow the BOARD OF TRUSTEES Albert W. Vontz III should be sent by email to: 16th edition of the Chicago Manual of Style. For The Filson Historical Society Book Review Editor Kevin Ward specific style guidelines, please visit The Filson’s web- William H. Bergmann Chair Donna Zaring are private non-profit organiza- Matthew Norman, Editor or LeeAnn Whites, Editor site at: http://www.filsonhistorical.org/programs- Department of History Edward D. Diller James M. Zimmerman tions supported almost entirely Ohio Valley History Ohio Valley History and-publications/publications/ohio-valley-history/ Slippery Rock University Asst. Professor of History Director of Research submissions/submissions-guidelines.aspx. -

Extensions of Remarks E1111 HON. BOB SCHAFFER

June 11, 1998 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD Ð Extensions of Remarks E1111 National Park Service the National Under- College embodied its founders antislavery Neil, George Passmore, Joseph Passmore, ground Railroad Network to Freedom program sentiments, and the school's location, atop the Ervin Queer, Hiram Smith, John S. Van to facilitate partnerships among Federal, state highest hill in the area, was a physical and Cleave, Jared Van Cleave, Henry Waddle, and local governments and the private sector symbolic statement of the community's beliefs. James Waggoner; RushÐTristan Cogeshall, to identify and commemorate the Underground Near West Franklin in Posey County, run- John H. Frazee, Johathan I. Gray, Henry Hen- Railroad. Commemorating the Underground away slaves were helped across the Ohio ley, Milton Hill, Sidiman Jessop, Henry Macy, Railroad Network is well-deserved and will River. Lake, Porter, and LaPorte counties all Robert Patterson, Zachareal Small, Abraham help every American understand what the Un- had places where slaves could be hidden until Small, Elisha B. White; SteubenÐLewis Bar- derground Railroad was and how it helped they could be smuggled on boats and carried nard, Capt. Butler Barry, Henry Butler, M.B. thousands of slaves to secure their freedom farther north on the Underground Railroad net- Butler, S. Seymour, S.W. Clark, Allen Fox, and their place in history. Through the pro- work. Denison Fox, J.A. Fox, Judge Gale, Hendry, gram, structures, routes and sites which were Evansville was another place where the Samuel Jackson, Augustus Kimball, S. significant to the Underground Railroad will be slaves crossed the Ohio River. The Indiana McGowan, Nelson Newton, Rev. -

AANDERSON FERRY. the Anderson

Encyclopedia of Northern Kentucky in partnership with NKY.com Introduction | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | Y | Z | Index The Enquirer/Patrick Reddy ANDERSON FERRY. The Anderson Ferry, lo cated on the Ohio River in north- eastern Boone Co between Constance, Ky., and the western part of between Constance, Ky., and the western part of Cincinnati, has been in continuous operation since 1817. George Anderson, born in Maryland in 1765, lived near the the mouth... A (cont’d on pg. 26) The Encyclopedia of Northern Kentucky Contents Introduction, Foreword, Acknowledgments and Guide for Readers Chapters: A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, I, J, K, L, M, N, O, P, Q, R, S, T, U, V, W, Y, Z Index, Bibliography, Illustration Credits Edited by Paul A. Tenkotte and James C. Claypool THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY Republished for the World Wide Web by NKY.com and Enquirer Media A Project of the Thomas D. Clark Foundation, Inc. Mark A. Neikirk, President Dave Adkisson, Treasurer Sherry Jelsma, Vice President Melanie J. Kilpatrick, Secretary Thomas R. Brumley, Immediate Past President Michael J. Hammons, Past President Board of Directors Dave Adkisson, Frankfort Michael J. Hammons, Park Hills Robert Ted Steinbock, Louisville Jane Beshear, Frankfort Sherry Jelsma, Shelbyville Mrya Leigh Tobin, New York City Thomas R. Brumley, Lexington Martha C. Johnson, Melbourne James M. Wiseman, Erlanger John S. Carroll, Lexington Mark A. Neikirk, Highland Heights Sara W. Combs, Stanton Alice Stevens Sparks, Crescent Springs Editorial Staff Editors in Chief: Paul A. -

Stephen Smith Had in 1831 Led Free Blacks in Columbia in a Public Meeting in Opposition to the Agenda of the American Colonization Society

GO TO LIST OF PEOPLE INVOLVED IN HARPERS FERRY VARIOUS PERSONAGES INVOLVED IN THE FOMENTING OF RACE WAR (RATHER THAN CIVIL WAR) IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Located just north of the Mason/Dixon line separating Pennsylvania from slaveholding states such as Maryland, the town of Columbia would be an important stop on the Underground Railroad. In 1818 its citizens had begun a Columbia Abolition Society. Stephen Smith had in 1831 led free blacks in Columbia in a public meeting in opposition to the agenda of the American Colonization Society. In 1834 he had joined with David Ruggles, John Peck, Abraham Shadd, and John B. Vashon, who were the initial black agents for Freedom’s Journal and later for The Emancipator. In that year and the following one there were riots in Columbia, white riots that made a particular target of the lumberyard of the successful “Black Steve” and his mulatto partner William Whipper, and in 1835 the Columbia Spy would report that his success had so “excited the envy or hatred of those not so prosperous and of the ruling race” that his office was vandalized and papers, records, and books destroyed. Smith relocated to Philadelphia leaving the business in Columbia under Whipper’s management, and would soon again be prospering. When abolitionists found it difficult to secure a building to hold their meetings, Smith made Pennsylvania Hall available for their use, but on July 17, 1838 a mob of white citizens torched that venue. Taking advantage of a little-known Pennsylvania statute by which a municipality could be held liable for mob damage, Smith sued Philadelphia, obtaining a judgment for damages in excess of what the building had cost: $75,000. -

John Hatfield: Barber, Deacon, Abolitionist by Betty Ann Smiddy

John Hatfield: Barber, Deacon, Abolitionist By Betty Ann Smiddy A barbershop in Richmond, Virginia by Lyre C. Rowe, 1853 The Illustrated London News (March 9,1861), vol. 38, p. 207. CC BY-NC 4.0. 2 www.cincinnatilibrary.org/tallstacks/voices/potter06.html Adapted from 1842 plan of Cincinnati (Courtesy of UC Archives and Rare Books Library). 3 John Hatfield was an active figure in Cincinnati’s anti-slavery movement. He worked as a barber to both blacks and whites, which gave him access to contacts and information in both communities. As a Deacon of Cincinnati’s Zion Baptist church and a member of the Cincinnati Vigilance Committee in the years before the Civil War, Hatfield’s connections made him a valuable member in international abolitionist circles. Even though he was named in many historical references written by Levi Coffin,1 Laura Haviland,2 and Professor Wilbur H. Siebert,3 until now, his life story and the fate of his family have never been explored in print. Hatfield died in Australia—a stranger in a strange land--leaving a legacy of compassion and quest for freedom. Through a series of remarkable coincidences, his family story can now be told. What follows places John Hatfield in the context of the history of his time. From Pennsylvania to the Queen City of the West John Hatfield, was born a free man of color (of mixed race, formerly known by the antiquated term “mulatto”) in Metal Township, Franklin County, Pennsylvania c. 1804 to Joseph and Catherine Moore Hatfield. Joseph was a farmer. Joseph and Catherine Moore Hatfield were the parents of John, Samuel, Charles Amos and perhaps other Hatfields as well. -

History of the Underground Railroad in Indiana

The Underground Railroad in Indiana While not comprehensive, this article attempts to place Indiana’s Underground Railroad into the greater context of United States history. This is only a start of information and should not be seen as a definitive study of Indiana. As more research, and time, allows we will add to the information. Slaves have been in America since the late 1500s. These Africans were captured, mainly in the western part of the continent, known as the Ivory Coast. Some were sold by their kings, others betrayed by rival tribes, and others simply kidnapped. They were sent to the New World, specifically the south of this country, the Caribbean, and South America. Every colony in the New World allowed for slaves and some of our most prominent leaders owned slaves: Thomas Jefferson, George Washington, Chief Little Turtle, and Jesuit missionaries. Slaves were brought into this country to help build farms and plantations, work in factories and also people's homes. Along with slaves there were also indentured servants doing some of the same work. An indentured servant is someone, usually white, required to work for a person for a set number of years. This servant was usually young, brought to the New World by the owner of their contract, and not paid for their work. They worked for free to pay off the travel costs and their room and board. Servitude lasted from several months to a life time, depending on circumstances. Years were added onto the contract for illegal actions, stealing from the kitchen, breaking items, or disobeying the contract holder. -

Around the Society... Officers: President After a Relatively Mild December, I Think Winter Has Arrived

January 2015 Around the Society... Officers: President After a relatively mild December, I think winter has arrived. At least the mild Penny Huber winter favored our Christmas Open House and our Christmas Dinner. Both Vice-President were successful events. Judie Crank Treasurer I want to tell you about a new project. Bruce Summe Secretary We have started an educational program with the third grade classes at South Lori Stanley Elementary School. We gave a powerpoint presentation on some early busi- nesses in Mt. Healthy comparing them to present day businesses. Providing Corresponding some items from the museum for the children to see and hold proved to be a big Secretary attraction. We will do a second presentation in early spring and then the children Julie Turner will visit the museum in late spring. Our programs are tailored to enhance the Board of Trustees: goals and objectives of the third grade curriculum. Dave Huser Jay Klenk Remember to support our Perkins Fundraiser. The third Wednesday of each Ken Scheffel month we Dine to Donate at Perkins Restaurant on Hamilton Avenue. When you bring a coupon and enjoy a meal, Perkins will donate 20% of your bill to the Mt. Healthy Historical Society Mt. Healthy Historical Society. This also includes carry-out and bakery items. 1546 McMakin Avenue Coupons are available at many businesses in Mt. Healthy and on our website, Cincinnati, OH 45231 mthealthyhistory.org. Phone: 513-522-3939 Have a good winter! Hours: 9-11 a.m. Tuesdays and Saturdays, 1-3 p.m. the Sincerely, first Sunday of the month or by appointment. -

2018 National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom Program

National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom Listing Members listed in red are part of the National Park Service (NPS) Alabama Edward T. Sheldon Burial Site at Mobile Evergreen Cemetery Wallace Turnage Historic Marker Connecticut Arizona Hartford Tempe Harriet Beecher Stowe Center Passage on the UGRR: A Photographic New London Journey New London Custom House Arkansas Delaware Bluff City Camden Poison Spring Battle Site Camden Friends Meeting House Helena-West Helena Dover Civil War Helena Tour Delaware Public Archives Freedom Park Delaware State House Pine Bluff John Dickinson Plantation Battle of Pine Bluff Audio Tour Star Hill Historical Society Museum New Castle California New Castle Court House Napa Odessa Mary Ellen Pleasant Burial Site Appoquinimink Friends Meeting House Riverside and Cemetery Footsteps to Freedom Study Tour Corbit-Sharp House Sacramento Seaford California State Library Tilly Escape Site, Gateway to Freedom: San Francisco Harriet Tubman's Daring Route through Harriet Tubman: Bound for the Promised Seaford, DE Land Jazz Oratorio Wilmington Meet Mary Pleasant/Oh Freedom Historical Society of Delaware Saratoga Long Road to Freedom: The Mary A. Brown Burial Site Underground Railroad in Delaware Sonora Rocks- Fort Christina State Park Old Tuolumne County Courthouse Thomas Garrett House Site Tubman Garrett Riverfront Park and Colorado Market Street Bridge Colorado Springs Wilmington Friends Meetinghouse and Cemetery District of Columbia Fort Mose: Flight to Freedom: Annual African -

Annual Report Report Michigan Freedom Trail Commission 2005 Executive Summary

Michigan Freedom Trail Commission 2005/06 AnnualAnnual Report Report Michigan Freedom Trail Commission 2005 Executive Summary Michigan’sMichigan’s Story Story Slavery was legal in the territory that would become Michigan until the adoption of the Northwest Ordinance in 1787. Michigan prohibited slavery when it adopted its first state constitution in 1835. The peo- ple who resisted slavery by escaping to Michigan, or by helping those who escaped, made this state a place where the conflict over whether any person could own another shaped communities and lives. Michigan’s Underground Railroad stories document the lives of African Americans who escaped enslavement in rural and urban communities and the strategies that anti-slavery activists used to challenge and dismantle slavery. These methods of resisting slavery included public demonstration, challenging and changing the law, forming anti-slav- ery organizations or religious congregations, holding public meetings, and speaking and writing against slavery. Black and white women and men in Michigan, who often knew each other through religious or political affilia- tions, provided African Americans who escaped slavery with safe places to hide, food and sometimes clothing. In 1861 the Civil War drew on long-standing conflicts between those who claimed to own African Americans as slaves and those who insisted that a human could not and would not be owned. African Americans who had escaped from slavery, and African and European Americans who had assisted them, used the war as an opportunity to even more directly challenge the system of enslavement. If they were of age to fight, many African American men in Michigan joined the 102nd regiment, while others served as organizers and promoters of the regiment.